Abstract

Lima, a city of ten million people, presents significant mobility difficulties, with a high dependence on relaxed means of transportation due to the worsening of the city’s transportation system. There are chaos in the streets, severe traffic, high fatality rates, and a perplexing public transportation system. All of this emphasizes Lima’s famed transportation problems. A regulation inaugurating the Authority for Urban Transport (ATU) was established in 2018 to improve the situation significantly. ATU unifies formerly distributed tasks across Lima and Callao metropolises, as well as the Department of Transport, and has the full support of the current administration. We concentrated on mitigating the problem’s deleterious effects through improvement of the public bus transport system in backing of ATU’s measures to tackle the conveyance problematic in the end. Approximately, 70 percent of the people take the bus, and with such a high degree of ride-sharing, fruitful reorganization has many potentials.

Introduction: Effects of Inadequate Public Transportation in Lima, Peru

The Transportation Infrastructure Is Under Increasing Strain

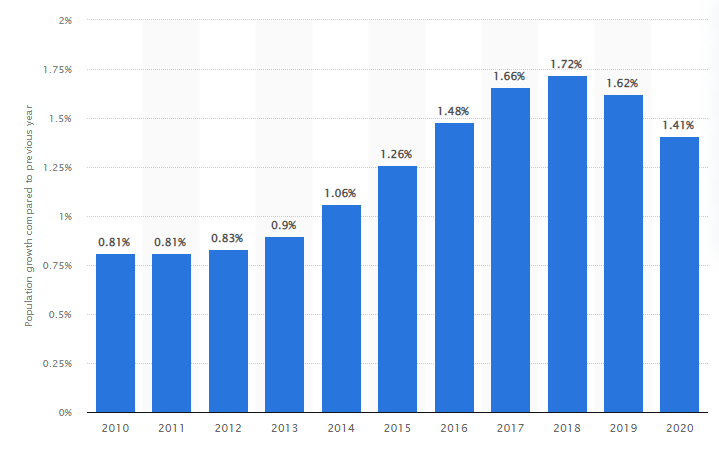

Peru has seen a steady increase in population in urban areas due to financial and communal causes. Lima, Peru’s capital and main metropolitan area, has engrossed most of those who have fled the countryside. Lima presently has a population of over 10 million people, accounting for roughly a third of the country’s total population. Even though the city’s population growth rate has slowed, it is still expected to expand at a pace of 1.5 percent per year. Equally, this population growth has resulted in a steady development of the country’s automobile fleet, which now accounts for two-thirds of all cars. Hence, this has created significant trials in the metropolis’s transport subdivision. Heavy traffic necessitates a more effectual system with affordable community conveyance for the city deprived.

The Present Public Transportation System’s Characteristics and Flaws

Lima generates over 12 million carrier travels every day, with 86 percent using public transportation. Lima’s public transportation system now consists of one BRT (Metropolitan) line, one metro line, and multiple bus routes. Even though the figure of travelers continues to rise, public transportation’s processing capacity is inadequate equated to traffic ultimatum. Though the bus is the most popular mode of community transport in the city, with 59 per cent of commuters using it, it also has the highest level of consumer discontent. Reasonably, it becomes difficult for the people who live on the outskirts of Lima in Peru to access transportation to their areas. Hence, the people will have to use extra money to get other transport services, which is expensive.

Poor design, execution, and control tactics have occasioned in a disorderly bus system and decreased consumer satisfaction. Numerous official and relaxed secluded bus workers provide a low-quality transportation service. Small-scale private operators compete on routes where they can pick up the most customers, using ageing, malfunctioning low-capacity vehicles. When this was combined with a growth in car ownership, significant traffic overcrowding developed through the day, even outdoor of highest travel periods. In some corridors, transit time has increased considerably, including undesirable externalities such as air contamination, noise, and traffic fortunes.

Changes in Administrative Capability Recently

The administrative entity in charge of Lima’s public transit has undergone a significant overhaul. Before the reform, the Metropolitan Municipality of Lima (MML) established three semi-public bodies to administer different aspects of public transportation. Protransporte which is the body responsible for the development of public transport projects in the Peruvian capital is handled by AATE (Autonomous Authority for Electrical Train). Lack of direction amid transport means, native conveyance advisors’ lack of knowledge and abilities, time-consuming inflexible procedures. Closely non-existent organization on connection transport concerning Lima and Callao comprises of Urban Lima, which were all obstacles posed by fragmentation.

ATU was established in December 2018 to supervise all public conveyance in Lima and Callao provinces. The particular public entity reports to the department of transport and has complete jurisdiction and practical and financial resources. Despite having absolute power over community conveyance in Cosmopolitan Lima, the ATU is currently absorbing functions from the municipalities of Lima and Callao and three semi-public agencies.

To solve the inadequate public transportation sector in Lima, the capital city of Peru, the government should improve the road capacity to the outskirts of Lima. Reasonably, the improvement of roads to the outskirts of Lima city will help the people living in the outskirts to save money. When they use moto tax or the walk by bikes, it is costly thus straining much when earning little money. Opening the roads to the outskirts will imply that the vehicles will reach out to the places, thus minimizing costs.

Identification of the Problem

Unsatisfying Public Bus Transportation Service

Rendering to a review conducted in 2018, a smaller amount than 16% of respondents were happy with bus provision. Microbuses, Complementary Corridors, and Metropolitan buses are Lima’s three types of buses. Traditional buses, combis, and coasters make up microbuses, which are privately owned. Metropolitan is highly punctual in its Bus Rapid Transit lines. Despite serving 89% of bus customers, microbuses are the nastiest, with at least 45% of the public rating their services as poor or extremely poor.

Each bus model has its own set of benefits and drawbacks. Microbuses are popular because of their long-range and affordable fares. However, characteristics such as promptness, hygiene, instruction, and safety are said to be inadequate. Because small-size bus operators handle coasters and buses. The Metropolitan and Complementary Corridors (CC) are substantially better in service, but their fares are expensive, and their coverage is limited.

Concerning the punctuality of the microbuses in Lima city, the people who commute from the outskirts never get in time to their workplaces. Since the microbuses do not arrive on time, it means that the people living in the outskirts will have to wait if they cannot look for other alternatives like using of bikes. By use of bikes which are readily available, they will arrive to their places of work on time thus able to execute their duties well.

The primary source of users’ unhappiness, according to the poll, is their apparent loss of time to get to their places of work. Individuals admitted that they had no idea when the microbuses would come to the bus picking places. Microbuses, for example, “come out of nowhere” and “nonentity distinguishes precisely where the automobile travels,” according to one source. Unpredictable bus arrival times give citizens the impression that public bus transit is unreliable. Due to the unreliability of car entrance times, there is a little anticipation of the current transport system, particularly in suburban areas. As a result, motorists avoid taking public transportation, aggravating traffic congestion. In 2018, 25 percent of the population spent an hour or more every day commuting one way from their residences to work or school15.

Another critical source of consumer unhappiness is transportation barriers. The use of disparate payment mechanisms for different modes of public transportation is inconvenient and slows down the travel operation. There is no transit discount system, which makes public transportation more expensive for both students and seniors. Furthermore, consumers find it difficult to navigate efficiently due to a lack of information on accessible routes and absence of transport groundwork that attaches various modes of transport. They cannot tell you which way is the firmest or greatest effectual in terms of transportation, and even if they can, getting off and finding the appropriate stop to catch the next bus is complex.

Overflow of Contending Buses

In terms of communal externality, contending means of transportation contribute to air pollution and noise by routinely breaching traffic laws, making for a dangerous driving environment. Excessive registration of public vehicles in the past has resulted in unneeded rivalry today. Because more than 30,000 cars are enumerated for community bus transportation in Lima, there is a risk of oversupply. About 63% of community bus transit vehicles are microbuses, which can only carry a minor figure of travelers due to their minor scope, making them ineffective on major public routes. Because of the fierce competition among bus companies, increased travel times are experienced due to traffic overcrowding on the city’s foremost highways. Furthermore, the appropriate authorities do not correctly discipline violations of traffic laws, leaving no enticement to follow the rubrics.

Problem Scrutiny

Bus Operators, Routes and Fares

Bus Operators

The bus system in Lima Metropolitan is divided into three categories: El Metropolitan which consist of dedicated bus lanes along the main road, Complementarians Corridors (CC), and microbuses. Reasonably, these three categories comprise of differerent routes that serve the passengers in and out of Lima. The present operating routes comprise one El Metropolitan route and 18 CC routes and 111 Microbus routes, according to bus types. Microbuses are the most common type of bus, but because 69% of them are over 15 years old, they contribute to a high risk of traffic accidents. Aside from El Metropolitan, other bus lines are not well armed with amenities such as chosen bus stopovers. Travelers can board and exit buses, and buses stop abruptly, endangering passengers’ safety and clogging traffic.

El Metropolitan is the city’s primary and only bus rapid transport (BRT) scheme, opening in 2010. Buses are circulated in special lanes that are closed to general traffic. It connects 18 Lima districts from Chorrillos in the south to Independencia in the north via a 27-kilometre route with 35 stops. Metropolitano feeder buses connect isolated neighbourhoods, and each terminus place helps as a terminal for other buses. Four southbound ways (Matellini Station) and eighteen northbound services (Naranjal Station). The system employs 300 bus navies with a combined aptitude of 60 passengers.21 Users must pay the Metropolitan fare of 1.5 soles (0.45 USD)before ascending raised stages, mechanically opening entrances when a pre-purchased electric card is swiped.

The Lima Municipality attempted to codify routes, regulate bus stations, reduce the usage of combis, unify rates, and improve drivers’ working conditions by introducing the Complementary Corridors. The Complementary Corridors are five lines that run across Lima’s principal avenues and are represented by the colours blue, red, yellow, purple, and green. Each colour line has its own “services” that travel down the same main streets but vary in the figure of stopovers, end stopovers, and incidence. The Blue line, the first complimentary corridor, was launched in 2014, despite objections from microbus operators and user complaints about overcrowding, as seen by long queues at bus stops. Complementary corridors are currently the most popular bus type in the city due to their accessibility, speed, association, and cleanliness and are the best-rated bus form accessible.

Many small-scale individual bus operators who serve the entire local area typically run microbuses. These old-fashioned modes of transport are favoured for their extensive coverage of the city and affordable costs. On the other hand, these buses are more prone to issues like ageing vehicles and erratic driving. To address working disorganization, ATU should aim for long-term publication of the scheme, focusing on limiting the overall number of microbuses and streamlining bus routes.

Bus Routes

Lima and Callao operate 415 routes, including 265 downtown routes, 77 suburban routes, 58 inter-city routes, and 15 others. The departure-stop-endpoint is labelled on the bus’s external for passengers, but the way map is not always accurate. Therefore, it is best to double-check with the bus driver afore entering. The concentration of bus routes exacerbates the situation. In Peru, there are roughly 460 bus companies, with the majority being small operations with a few buses. These small enterprises typically operate solely on routes where they can generate money, resulting in route dismissal and disputation. Bus workers are centred on “the surplus line,” or major thoroughfares, while residential parts with less riders are underserved. Due to the intense rivalry, each route has a significant disparity in working bus figures and navy intermissions, reducing the competence of the bus system and the effectiveness of bus operators alike. There is a need to combine bus operators from an institutional aspect. The general bus functioning scheme, which determines the correct figure of buses for each path and the navy intermission and the regulations that ensure the scheme’s upkeep, is obligatory.

Bus Fare System

There are dissimilar tariff methods for Lima bus rapid transport (BRT), Metro, and conventional buses. BRT and Metro passengers pay with an automated transport card, while others pay with cash. The incompatibility of BRT and Metro cards, because the worker is dissimilar for each, necessitates the operator to own equally transport cards, which adds to their pain. Furthermore, BRT and Metro use a standard fare rate, which creates an issue of equity between short- and long-distance riders. However, the fare structure in Microbuses is unclear because the bus conductor has the discretion to adjust the fare. Some credit unions have recently adopted an electric card called “Lima Pass,” but it is only valid for certain lines.

Furthermore, there is no discount mechanism for transit, which raises the economic burden on customers. Lima and Callao’s urbanization spreads to the outskirts, resulting in lengthier commute distances for users and a greater variety of community transit options. As a result, in the existing system, fares are fixed for each mode of transportation. Thus, commuters who utilize two or more must pay comparatively expensive fees. For instance, paying for a bike from the resident’s place to the bus station for 0.3 soles and also from the bus station to town for 1.5 soles is quite expensive. Increased use of personal automobiles exacerbates traffic congestion and environmental issues.

Valuation of the Level of Informality

Synopsis of the microbus scheme

Lima has around 32,500 buses, compared to Tokyo, a city of comparable size and population. Microbuses account for 31,118 of Lima’s entire bus fleet, or 96 percent. It is the primary cause of public transit disruption, yet it also delivers affordable and reachable transport to the metropolis’s working-class. Microbuses should be respected for their flexibility, coverage, and economical service to low-income neighborhoods on the metropolis’s outskirts. Still, Lima should not overlook the current Microbus scheme’s challenges. Rendering to a 2012 World Bank analysis, the metropolis’s increasing bus navy has rendered Lima one of Latin America’s most polluting cities. Furthermore, overcrowding and ineptitudes in the urban transport system result in a loss of $400 million a year. Microbus segment restructuring is required to build and provision a long-term urban transport scheme. Equally, it is appreciative why microbus segment restructuring was created, what ecology it operates in, and which features of residents’ demands it meets will aid in the development of a strategy to ratify the scheme with minimal disturbance.

Background of microbuses

Surprisingly, Lima’s current state of chaos was headed by a well-organized bus scheme. The state-owned National Urban Transport Company (ENATRU) buses were well systematized and pleasant. Still, they were woefully inadequate, especially considering the city’s rapid population growth in the 1960s and 1970s. During the 1980s, the state had a tight grip on the bus public transit system.

The microbus system is based on a sophisticated paradigm designed in the 1990s to allow private bus operators to operate on public bus routes. It gave for-profit transportation companies the ability to warrant community bus paths. President Alberto Fujimori began freeing Lima’s bus transport linkage in 1991 due to unemployment and supply shortages. Lawmaking Decree 651 changed the Community Bus Conveyance System into a permitted marketplace. The bill mandated pricing rivalry and unrestricted entrance to paths. It also allowed any legal or usual person with municipal authority to deliver this service with nearly any vehicle. The state-owned ENATRU was disbanded in 1992, and its buses were vended to private transportation companies. The scenario swiftly devolved into a bus oversupply, aided by Decree 080-91-EF, which eased restrictions on the entry of secondhand vehicles. By 1993, there were over 323 new bus lines, and private companies were authorized to operate them, import vehicles, and determine their prices. The city featured 570 bus lines used by 257 different transportation providers by the early 2000s.

Thanks to the legislation, private transit firms might lease their ways to vehicle proprietors, who could then hire the vehicles to drivers and gleaners. According to the information, daters shout, drivers would choose whether to pick up travelers or simply pass by the bus stopover. To survive with the existing low fares (usually USD 0.3), they occasionally overlook red signals and hasten on yellow lights to pick up extra people ahead of the competition. The “Penny War,” a situation of intense rivalry among drivers to gain more travelers, resulted from this labor arrangement. Henceforth, the deregulation of the community bus system decoded into traffic overcrowding triggered by the overlay of paths, extreme vehicle navies, and irresponsible driving. Augmented functioning times for drivers and price gleaners have exacerbated the present misconducts. Even though combis appealed to carriers because of their low cost and high flexibility, residents evaluated them poorly in comfort and law-abiding behaviour.

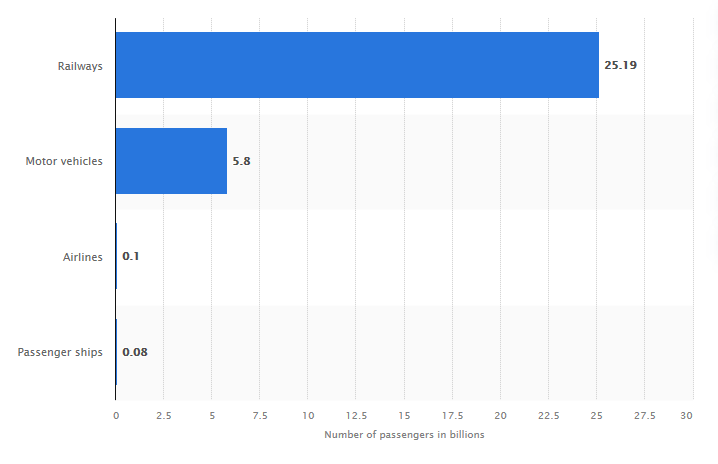

A Comparison of the Public Transportation in Japan

Railways are a vital mode of passenger transportation in Japan, particularly for mass and high-speed transportation between large cities and commuter transportation in urban regions. Most of Japan is covered by seven Japan Railways Group businesses, state-owned until 1987. Commercial rail businesses, regional governments, and companies sponsored by provincial governments and private companies conduct railway services. Reasonably, the use of trains in and around the major cities of Japan is relatively cheap which is 170 Yen (1.33 USD)than the use of microbuses and buses in Lima, Peru which is 1.5 Soles. Sensibly, it is an advantage to the people of Japan, and this boosts their income, as they do not strain so much to reach their places of work. Railroad transportation is Japan’s primary mode of public transportation, covering everything from trams to Shinkansen (bullet train) lines for long-distance travel. The railway is undoubtedly the essential mode of public transit in the archipelago, as it carries the most passengers and generates the most significant traffic.

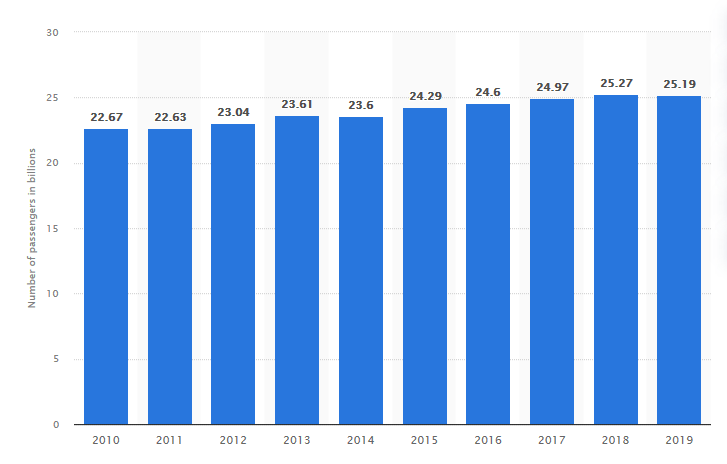

The number of passengers transported via railway transportation in Japan in the 2019 fiscal year was over 25 billion, a slight decrease from the previous year. Unlike the public transportation in Lima, Peru, the Japanese are crucial as they connect people around and across major cities. With cheap train public transportation, the country’s economy will be boosted much as people will get to generate more income which will generate revenue for the government from their places of work. Equally, it implies that the people living on the outskirts of major cities such as Tokyo can access very affordable and on-time transport. Sensibly, the people living in the areas on the outskirts of Tokyo can get to their places of work on time, thus boosting the country’s economy. Practically, when people or workers arrive early and on time at work, they can attend to their clients, do business exchanges on time, and generate a good income. Equitably, by developing a good income, the government of Japan will collect tax from the business, thus boosting their economy.

In comparing the public transportation between the two countries, or rather the two cities in Peru and Japan, Japan is much better and more affordable to the residents which is 210 yen. The residents do not strain much, be it first-class, middle-class, or lower class. Both people of different categories can access public transport at affordable prices, and the public transport can drop them at their various places of residence. In Lima, Peru, the public transportation of microbuses and buses cannot reach the outskirts of Lima city because of poor transportation. Conversely, it means that the people who live on the outskirts will have to find their ways to get home. Equally, they will have to find ways to reach town places or places where the microbuses and the public buses can be accessed to reach to their work areas. Hence, it is time-consuming for Lima, Peru, compared to the people of Tokyo in Japan, who have easily accessible means of transport and are punctual.

Regarding the graph above on the number of passengers and the different public transport in Japan, people use railways more than motor vehicles, airlines and passenger ships. Reasonably, passengers prefer trains because they reach out to their places of residence, which are based on the outskirts of Tokyo and other major cities in Japan. In Lima, Peru, passengers use public buses and microbuses, but these means of transport never reach the outskirts of Lima city.

Making changes in Public Transportation in Lima, Peru

A Memorandum of Cooperation (MoC) on transportation has been signed between Peru’s Transport and Communications Ministry (MTC) and Japan’s Department of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism. The contract will permit for sharing of data, involvements, technologies, and best performs to help both economies grow together. For that purpose, Transport and Communications Minister Elmer Trujillo travelled to Japan for a functioning visit, which culminated in a conference with his Japanese colleague, Keiichi Ishii. The collaboration covers land, airborne, and nautical conveyance; transportation safety; technological solicitation; execution and action of Integrated Urban Transport Systems; a highway, railway, and watercourse conveyance; and other disciplines of communal interest. Equally, when all these are implemented, it will help to transport workers to the outskirts of Lima town due to good infrasctructure courtesy of Japan and Peru collaboration.

Concerning the signatory between Japan and Peru on public transport, it typically means that Peru will be able to transform its transportation sector to make sure that the people in the area are well catered for. Equally, by being well catered for, it means that the people living in the outskirts will get good infrastructure, which will help make sure that public transportation is accessible to the people living in the outskirts of Lima.

Most microbuses in Lima, Peru, are dirty, so they are not conducive for people to use. It is against the hygiene that people should enjoy, which puts their lives at risk. Compared to the public transportation of Japan in Tokyo, Japan, the public transport, which is through trains, is very clean for the passengers to use. Public transportation is rarely delayed unless there is a very compelling reason, and it is swiftly restored. Besides being on time, public transport is also spotless and comfortable, making the overall experience very pleasant.

Challenges To Reform the Problem behind Microbuses

The political backlash, which would affect many drivers and fare gatherers, vehicle proprietors, and transport businesses, is an essential deliberation before the improvement, which aims to solemnize the transport scheme dramatically. The influence on drivers and fare gleaners is particularly significant, as they often come from low-income backgrounds and may find it difficult to reintegrate into the labor marketplace. The informal Microbus ecology, which includes fare gleaners, wayside merchants, and window liners, relies on the present employment scheme, thus alteration is difficult. They all agree that modification is essential, and Lima’s upcoming hinges on it figuring out how to get out of the transportation impasse.

Lima’s urban transportation system has become unsustainable in the early 2000s, necessitating a comprehensive reorganization. The system has to deal with an increase in traffic accidents and hefty running costs. Congestion, average travel times, and public transportation costs were all high. Gas usage was also increased because of these inefficiencies. This condition, along with the high levels of air pollution emitted by an antiquated fleet, posed a continuing health risk and a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions. The public transportation system was of poor quality. Access to buses for those with reduced mobility was, at best, limited. Women, in particular, we’re concerned about their safety and security.

Administrative Analysis

The Authority for Urban Transportation (ATU), a particular practical group under the Office of Transport, was established in December 2018. Its aim was to integrate clumsy transport creativities in the Lima and Callao jurisdictions to lessen travelling time, conveyance prices, and traffic congestion, use of secluded conveyance, and contaminating releases. The mission of ATU is to design, adjust, succeed, administer, and endorse the effective process of Lima and Callao’s Integrated Transportation System.

The absence of a complete chief strategy insures the entire conveyance scheme, as well as the deficiency of connectivity among numerous modes of transport such as BRT, steady buses, and Metro. Lack of direction amid Lima Metropolis and Ministry of Transport initiatives, demonstrate the disintegration in the Transport Scheme that ATU pursues to address. Another issue is the dispersion of transport figures produced by several divisions within Lima Municipality and the Department of Transport. This results in a public transportation system that is inefficient, slow, and expensive, and there is a more robust demand for private Microbuses. ATU will now take over the responsibilities of the Lima Municipality’s Urban Transport Management function, BRT management function, Callao Municipality’s Urban Transport General Management role, and the AATE’s Metro management function, as per its establishment statute. This reform is projected to result in the integration of various modes of transportation, their routes, and payment methods and the formation of a single collection system.

In keeping with this amalgamation, ATU’s Panel of Executives comprises of eight members. Each of them is appointed for a five-year term and includes two associates suggested by the Department of Conveyance. Similarly, one of whom serves as the Board’s President, one member suggested by the Department of Budget, another by the Department of Housing, and four members submitted by the Regional Metropolises based on their populace size. ATU is not yet fully operational due to its recent inception and ongoing functional and physical transfers of offices and equipment; however, it is scheduled to be operating in complete potency by June 2020.

Policy Recommendations for the Problems

The landscape of Potential Solutions

The setting up of cableways and raising the aptitude of the highway itself are two policy options for improving public transportation services that have recently attracted media attention. There should be an evaluation of these and other policy options in light of Lima’s specific topographical features and relationship to the city’s overall transportation strategy. Evaluating the Lima region’s landscape will help solve the problems experienced by public transportation. More roads will be opened to the outskirt of Lima town, making it simple for the microbuses to offer transportation services to the outskirts of the area.

Cableway Project

In contrast to La Paz, which is situated at 3,600 meters and has steep slopes, making old-fashioned civic transport challenging, Lima is primarily on the level terrain of the Peruvian coastal plain. The construction of a cableway would make it easier for individuals who live in difficult-to-reach hills and are low-income to connect to main roadways. The political support for this strategy is likely to come from the proposal’s intended recipients, who would benefit from a more contented and speedier journey if the fare remained inexpensive. This approach is not technically correct since it flops to discourse the general loss of time in the scheme, traffic overcrowding, and many barriers to travel. Furthermore, it is monetarily pricey, which would make implementation difficult.

Building new infrastructures or increasing current highways is expensive and difficult to include without disrupting traffic flow during development. Building of tunnels and bridges and a peri-urban by rail is a second policy option for alleviating Lima’s traffic congestion. Though it could ease traffic congestion in the downtown area by providing reliable routes, it would cause significant inconvenience in the near term by adding to the already overburdened conveyance scheme during the building stage. As a result, it has long-term political support, although it will confront opposition throughout execution. Additionally, it is a costly option that does not discourse numerous of the current system’s inadequacies but rather delays addressing the core reason by provisionally easing its symptoms.

Regarding the inadequate transportation in Lima, Peru, I suggest a set of comparatively low-touch strategies to discourse the highly interrelated problems identified. Equally, this will address the issues of; time waste due to traffic overcrowding and problems to transportation, such as dissimilar tariff assortment techniques and lack of info on the finest ways to take. These two alternatives do not adequately discourse them in the short-term. Information, Transit, and Standardization (ITS) are the three pillars of my policy package.

Implementing the ITS policy package has many advantages to alleviate the problems facing people living on the outskirts of Lima, Peru. Equally, the benefits include; augmented info distribution, confederacy of disbursement techniques, transportation reduction, calibration of buses, and path rationalization. Reasonably, this can immediately ease the transport scheme glitches in City Lima, as it does not need significant reserves or face robust partisan antagonism.

A Bus Information System (BIS) delivers users with real-time bus entrance info while also enhancing bus process efficiency by checking and regulating bus intermissions. This set of steps is technically correct because it directly addresses system inefficiencies that upshot in an unnecessarily long and costly travel. The apparent “misused” time at the bus stopover is exacerbated by the lack of information on arrival times. BIS prices vary based on the figure of bus navies, Automatic Vehicle Location (AVL) technology level, and other procedural mechanisms. Still, they are not comparable to the Cableway plan.

To enhance user convenience, practical normalization of the fare assortment scheme and disbursement technique is required. Transportation card technology is available on the BRT and Metro; however, whatever technology should be used as a standard requires further investigation. The technological foundation for espousing the transit reduction strategy will be a unified price scheme amongst community transport modes, which will result in a supplementary cheap community bus conveyance scheme. Finally, a road toward more formalization must be followed to advance the insight of chaos that now defines old-fashioned microbuses. The standardization of microbus colours, while seemingly insignificant, may enhance route communication and translate into a higher feeling of formality in the system, resulting in behavioural shifts among customers and drivers toward a more law-abiding attitude.

Policy Proposal to Fix the Transportation System in Lima, Peru

The research aims to employ ITS to give users important information, advance bus processes, and make the bus scheme cheaper. The strategy aims to increase bus operation efficacy and user suitability by using BIS to monitor and manage real-time bus positions to help operators choose the most effective bus way to their terminus. Citizens will be able to get reliable bus arrival information from BIS at each bus stopover via a built-in exhibition or a smartphone application. This will lower transit riders’ apparent and real wait times and help the conveyance midpoint accomplish bus navies well. The strategy is technically correct because the elucidation is well defined, with explicit mechanisms of what it would take to make it function, and presentation is guaranteed when implemented flawlessly.

Furthermore, it is politically acceptable, given that BIS reports an average of 90% user satisfaction in metropolises across the globe, which obviously leads to well bus navy supervision. The system gives passengers info such as projected arrival period and direction facts. Existing bus workers would not feel threatened because it would not restrict their operations directly but somewhat improves their management capabilities. Bus operators benefit from the system because it reduces total costs by maximizing bus operation efficiencies by minimizing low-operating navies and petroleum costs. In addition, the scheme will use the Fleet Monitoring & Control (FMC) tool to monitor and control driver patterns to ensure bus safety and punctuality.

Conclusion

In conclusion, improving the transport sector for the people living on the outskirts of Lima, Peru, should be a priority. Reasonably, by putting the infrastructure first, the people living in the outskirts will be able to pay and enjoy the privileges. By enjoying the benefits, it literally means that they will be able to arrive at and from work on time but at a cheaper transportation means. The people will be able to pay taxes well without much straining, and the government will, in turn, boosts her economy well, thus opening more road networks to the outskirts of Lima city. Equitably, by borrowing the transportation ideas from Tokyo, Japan, Lima will help her citizens who strain much when it comes to transportation outside the city.

Bibliography

Altieri, Marcelo, Erza Raskova, and Álvaro Costa. “Differences in railway strategies: The empirical case of private, public-owned, and third-sector railways in Tokyo.” Research in Transportation Business & Management (2022): 100787.

Edelman, David J. “Managing the urban environment of Lima, Peru.” (2018).

Espinoza‐Ramos, Luis A., Renzo Pepe‐Victoriano, Jordan I. Huanacuni, and Manuel Nande. “Effect of transportation time and stocking density on seawater quality and survival of Anisotremus scapularis (Perciformes: Haemulidae).” Journal of the World Aquaculture Society (2021).

Guenette, Justin Damien. “Price Controls: Good Intentions, Bad Outcomes.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 9212 (2020).

Gorka, D. Japan: public bus passenger volume | Statista. [online] Statista. Web.

Guevara, R. Exploring BRT in Lima, Peru. Multiple Cities. (2017). Web.

Herreros-Irarrázabal, Diego, Juan Guzmán-Habinger, Sandra Mahecha Matsudo, Irina Kovalskys, Georgina Gómez, Attilio Rigotti, Lilia Yadira Cortés et al. “Association between active transportation and public transport with an objectively measured meeting of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and daily steps guidelines in adults by sex from eight Latin American countries.” International journal of environmental research and public health 18, no. 21 (2021): 11553.

Jauregui-Fung, Franco, Jeffrey Kenworthy, Samar Almaaroufi, Natalia Pulido-Castro, Sara Pereira, and Kathrin Golda-Pongratz. “Anatomy of an informal transit city: mobility analysis of the metropolitan area of Lima.” Urban Science 3, no. 3 (2019): 67.

Kumar, Ajay, Sam Zimmerman, and Fatima Arroyo Arroyo. “Myths and Realities of Informal Public Transport in Developing Countries.” (2021).

Kawamura, Koichi. “International Trade of Used Trains: The Case of Japanese Used Rolling Stock in Indonesia.” In International Trade of Secondhand Goods, pp. 31-61. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2021.

Kutela, Boniphace, Norris Novat, and Neema Langa. “Exploring geographical distribution of transportation research themes related to COVID-19 using text network approach.” Sustainable cities and society 67 (2021): 102729.

Levy, A. Four ways to build a better bus system. DC Policy Center. Web.

Namgung, Hyewon, Makoto Chikaraishi, and Akimasa Fujiwara. “The influence of real and video-based experiences on subjective acceptance of a new transport environment: A case from Hiroshima, Japan.”

O’Neill, Aaron. Statista. Web.

Oviedo, Daniel, Lynn Scholl, Marco Innao, and Lauramaria Pedraza. “Do bus rapid transit systems improve accessibility to job opportunities for the poor? The case of Lima, Peru.” Sustainability 11, no. 10 (2019): 2795.

Ravet, Fabien, Fabien Briffod, Alexandre Goy, and Etienne Rochat. “Mitigation of geohazard risk along transportation infrastructures with optical fiber distributed sensing.” Journal of Civil Structural Health Monitoring 11, no. 4 (2021): 967-988.

Ramírez, Juan José, Juan Arenas, and Freddy Paz. “Design Process of a Mobile Cloud Public Transport Application for Bus Passengers in Lima City.” In International Conference of Design, User Experience, and Usability, pp. 375-388. Springer, Cham, 2018.

Romero, Yovitza, Norvic Chicchon, Fabio Duarte, Julien Noel, Carlo Ratti, and Marguerite Nyhan. “Quantifying and spatial disaggregation of air pollution emissions from ground transportation in a developing country context: Case study for the Lima Metropolitan Area in Peru.” Science of The Total Environment 698 (2020): 134313.

Scholl, Lynn, Oscar A. Mitnik, Daniel Oviedo, and Patricia Yañez-Pagans. “A rapid road to employment? The impacts of a bus rapid transit system in Lima.” The Impacts of a Bus Rapid Transit System in Lima (2018).

Stiglich, Matteo. “Unplanning urban transport: Unsolicited urban highways in Lima.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 53, no. 6 (2021): 1490-1506.

Quistberg, D. Alex, Thomas D. Koepsell, J. Jaime Miranda, Linda Ng Boyle, Brian D. Johnston, and Beth E. Ebel. “The walking environment in lima, peru and pedestrian–motor vehicle collisions: an exploratory analysis.” Traffic injury prevention 16, no. 3 (2015): 314-321.

Yang, Yunjung, and Rosemary Ulfe. “Addressing Lima’s Bus Transportation Fiasco.” PhD diss., Harvard University, 2020.