Background overview

Entrepreneurs share similar problems in terms of access to sufficient capital to start their business, ability to attract customers, developing a sufficient cash flow to sustain their venture and a variety of other issues that are involved in the process of developing a business (Zahra & Wright 2011, pp. 67-83).

In this section, the various methods of capital access available to entrepreneurs within Saudi Arabia, and the difficulties that are associated with the process of obtaining sufficient funds to start a profitable business venture will be analyzed.

Considering the fact that it is one of the wealthiest nations in the world, and part of the G20 group of states, the low rate of growth for its entrepreneurial sector engenders a number of questions that necessitates further research and analysis. It is expected that this section will act as the basis behind an assessment that would create effective suggestions as to how entrepreneurs within the country can best respond to various financial opportunities and challenges.

Saudi Arabian Economy and SME

SMEs in Saudi Arabia

A majority of the start-up businesses in Saudi Arabia are in form of SMEs. Within the study Leading the way (2005, pp. 78-79), it was explained that in most market economies, small to medium scale enterprises (SMEs) make up the bulk of a country’s enterprises. This constitutes 80 to 90 percent of local businesses (Leading the way 2005, pp. 78-79).

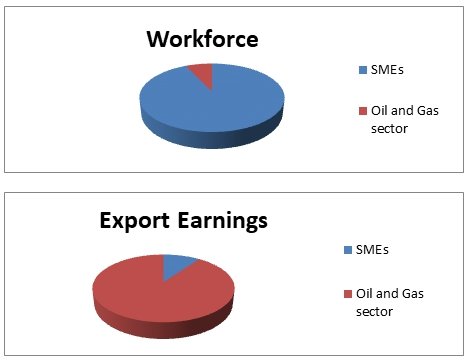

Such an orientation can also be seen in the case of Saudi Arabia, wherein SMEs make up 92 percent of local businesses within the country, and employ up to 80 percent of the workforce (Leading the way 2005, pp. 78-79). H.M. King Abdullah bin Abdul Aziz Al-Saud himself has been quoted as stating that “entrepreneurs are the backbone of the Saudi Arabian economy and are instrumental towards its continued growth and prosperity” (Kayed & Hassan 2010, pp. 379-413).

(Kayed & Hassan 2010, pp. 379-413)

It must be noted that despite the fact that SMEs constitute 92 percent of local businesses, they are still overshadowed by the country’s oil and natural gas industry which accounts for 90 percent of export earnings, 45 percent of the GDP and 80 percent of the government’s budget revenues (Kayed & Hassan 2010, pp. 379-413).

This is in sharp contrast to the situation found in countries such as the US, UK, China and other industrialized countries where local SMEs make up more than 70 percent of GDP, 60 to 70 percent of local government revenue and 75 percent of export earnings (Kayed & Hassan 2010, pp. 379-413).

While Saudi Arabia’s status as an oil exporter does entail a decidedly different economic structure, it must be noted that given the non-renewable state of its oil reserves, it is absolutely necessary to implement some measure of encouraging the development of start up businesses in order to have a strong local economy in place that is not dependent on resource that will inevitably dry up (Lindsey 2011, pp. 1).

Entrepreneurial Growth Rate (Saudi Arabia 2012, pp. 1-18) (Outlook for 2011-15: Economic policy outlook 2010, pp. 7-9)

Unfortunately, an examination of the development of local industries within the country reveals that entrepreneurial growth has remained low at 3.3 to 3.5 percent annually, with the much-lauded Saudi Fast Growth 100 group (a listing of the top 100 locally owned corporations that were started by entrepreneurs) gaining a combined annual revenue of $2.4 billion equivalent to $9 billion Saudi Riyals) with 90 percent of their revenue originating from within Saudi Arabia itself (Outlook for 2011-15: Economic policy outlook 2010, pp. 7-9).

While $2.4 billion may seem like a significant sum for the accumulated revenue of the top 100 companies within Saudi Arabia, this pales in comparison to the hundreds of billions accumulated by the top 100 companies started by entrepreneurs in countries such as the US, UK, and China. Even a developing country such as the Philippines has a local SME industry where the top 100 companies started by entrepreneurs reach revenues of $10 billion or more.

The fact that the revenue of these companies mostly originate from within the Saudi Arabian economy itself rather than through international exports shows how relatively “young” the companies started by local entrepreneurs are within country considering the fact that focusing on local instead of external markets is one of the first stages of entrepreneurial activity.

Such factors can be considered indicative of a major problem existing within the Saudi Arabian entrepreneurial landscape, which can be connected to the lack of sufficient access to funding for local entrepreneurs in order to sufficiently grow their businesses to a level that can be considered internationally competitive.

Saudi Arabia’s economy

According to Economic Structure and Context (2012, pp. 16-17), Saudi Arabia’s economy is heavily dependent on its oil reserves. This is because oil is the major export commodity in this economy. Additionally, the oil industry provides employment to a majority of the citizens. This implies that this economy is susceptible to the volatile oil prices in the world market, and any changes in the production of oil by the oil industry.

To address this vulnerability, the government has acquired a number of foreign assets which help in cushioning the economy against changes in the oil prices, which affect the economy adversely. For this reason, the economy is able to withstand shocks in the oil world market provided that it is not for an extended period (‘Chapter 2: Economic Outlook’ 2011, pp. 15-23).

It must be pointed that the government continues to be the major player in the economy. This implies that the economy is not fully liberalised.

However, the government is at the forefront in encouraging entrepreneurship with a view to increasing employment opportunities for the youth, who form the bulk of the kingdom’s population. This increased employment level, as a result of increase in private investment, will have the effect of enhancing the standard of living in the kingdom (Economic Structure and Context 2012, pp. 16-17).

Government’s involvement in the economy has helped in improving the standards of living for the Saudi nationals (Jacknis 2011, pp. 107-116). However, this involvement has repercussions that include: distortion of the market, subdued productivity, and discourage competition.

It can be said that the government’s dominance in the economy has lowered the efficiency of the economy. Nonetheless, the government has been working towards liberalization of the economy and complying with international treaties, with a view to improving the economy.

The Saudi government has also embarked on the privatisation of the some sectors of the economy, including: telecommunication, water and aviation. The major objective of this privatization has been to attract foreign investment in the economy. This will serve as the much-needed boost to propel the economy to a higher growth trajectory.

Moreover, the government has also increased public expenditure as a stimulus for economic growth. This increased public expenditure has been instrumental in facilitating the growth of Saudi economic cities that have acted as an incentive for the entrepreneurs (Economic Structure and Context 2012, pp. 16-17).

Literature Review

This section explores various aspects related to the financing of entrepreneurial ventures within Saudi Arabia, the way in which financial institutions and loan processes operate, as well as the current state of key funding sources in relation to their counterparts in other countries.

It is expected that through an examination of such aspects of the Saudi Arabian entrepreneurial and financing sectors of the economy, a greater degree of understanding regarding the current state of venture financing and the processes involved in it will be developed.

The Financing of Business Ventures within Saudi Arabia

One of the oddest discrepancies that has come up during the research process is that despite the fact that Saudi Arabia is widely recognized as a leader in promoting and supporting entrepreneurial activities, it actually has a financial sector that is not as conducive towards small to medium business loans as one might expect (Ahmad 2011, pp. 610-614).

It is usually the case that if a country is known for supporting entrepreneurial activity, this would in turn result in a commensurate effect on its local banking sector wherein loans for small to medium scale enterprises and ventures would be more readily given.

However, this is not the case and in fact it is actually more difficult to obtain these types of loans within Saudi Arabia as compared to other countries within the same region (i.e., the UAE, Egypt, Jordan, Israel etc.) as well as in countries such as China, the UK and the US (Ahmad 2011, pp. 610-614).

In order to address this rather odd disparity, an examination was conducted as to how small and medium scale enterprises were normally funded and how did this type of funding differ from what can be seen in other countries.

It was seen that in the case of Saudi Arabia, the family played a crucial role in the funding and development of start-up business ventures wherein more than 75% of local businesses started by entrepreneurs were a result of family members contributing towards the initial starting capital of the entrepreneur and actively gave advice regarding the proper management of the business (Constraints on Development: Small Businesses in Saudi Arabia 1992, pp. 333-351).

In fact, it was noted by researchers in the report Constraints on Development: Small Businesses in Saudi Arabia (1992, pp. 333-341) that it is the strong interfamily ties within the country’s culture that limits the export market of Saudi Arabia due to the development of a business culture, wherein it has become preferable to deal with family members or friends of the family when it comes to joint business ventures and business opportunities, which in effect severely curtails the ability of a business to expand beyond its current market due to the inherent hesitance in dealing with the unfamiliar (Constraints on Development: Small Businesses in Saudi Arabia 1992, pp. 333-351).

Going back to the issue of family and its connection to the financing of small to medium scale enterprises, what must be understood is that the proliferation of family as one of the primary methods of financing entrepreneurial business ventures has actually resulted in the local banking sector developing in such a way that they cater more towards large scale enterprises or higher tier medium scale businesses as compared to small or lower-tier medium scale companies (Chapter 4: Business Environment 2012, pp. 27-33).

The problem with this is that this in effect isolates a large percentage of the local population who do not have access to considerable family funds to start their business.

Such a situation is in stark contrast to the way in which the banking sector in other countries such as China, the US, the UK and even in certain sectors in the Middle East work, since it is often seen that investing in entrepreneurs creates numerous beneficial actions (i.e., better local economy, greater amount of deposits, helping out what could potentially develop into a larger enterprise, etc.) which banks generally think of as “safe bets” when it comes to loans, especially when it comes to the attitude of entrepreneurs to pay back what they owe on even if a particular business did not turn out as successful as expected (ST 2000, pp. 42) (Mahdi1998, pp. 1970-1971).

It is often the case that such individuals within Saudi Arabia have to rely on their own personal savings as their primary method of creating start-up capital, which is an incredibly laborious and time-consuming process, which would, of course, slow down the process of entrepreneurial activity within any country that utilizes such a system (Chapter 4: Business Environment 2012, pp. 27-33). Evidence of this can be seen in Saudi Arabia’s 3.3 to 3.5 percent annual entrepreneurial growths, which shows the negative impact that the current loan system has on creating better entrepreneurial activities within the country (Chapter 4: Business Environment 2012, pp. 27-33).

The inherent weakness of the “family fund system” currently utilized by a vast majority of entrepreneurs is that when it comes to expanding the business beyond its current form and structure, this is when family members at times balk and refuse to or are unable to provide the necessary funds for the development of the business beyond its current form (Siddiqi 2008, pp. 44).

The reason behind this is a plethora of issues ranging from the belief that after a business has been established, an individual should be responsible for its own expansion or that expansion itself is potentially risky without sufficient added benefits (Siddiqi 2008, pp. 44).

As a result, this curtails the potential for various entrepreneurial ventures to expand to foreign locations and this is evidenced by the fact that nearly 90% of all local entrepreneurial revenue is derived from within the Saudi economy alone instead of through outside ventures (Siddiqi 2008, pp. 44).

It must also be noted that another problem with the “family based” method of funding is that it actively promotes insufficient market examinations and a more lax behaviour when it comes to developing processes that are more efficient and less costly (Robson, 2005pp. 40-42).

Based on the study by Constraints on Development: Small Businesses in Saudi Arabia (1992, pp. 340), it was noted that family-based methods of funding were considered a relatively “safe” and “easy” method of funding for a business, which did not have the same stringent procedures and viability checks that are necessary when it comes to a bank loan (Footwear Industry Profile: Saudi Arabia 2012, pp. 1-29).

As such, entrepreneurs under this particular system are less likely to favor processes that maximized the usage of capital and utilized more efficient methods of operations due to the rather “easy” way in which funds could be obtained to run a business (Constraints on Development: Small Businesses in Saudi Arabia 1992, pp. 333-351).

This, Baqadir, Patrick, & Burns (2011, pp. 551-559) remark, is one of the main reasons why plenty of businesses fail within the first year of operation in Saudi Arabia, since it is usually the stringent process of loan evaluation seen in most banks that encourages entrepreneurs to think ‘outside the box’, resulting in financial success and ingenuity (Baqadir, Patrick, & Burns 2011, pp. 551-561).

Though not particularly as relevant, it must be noted that there is also another socially based reason as to why certain entrepreneurs are experiencing a higher degree of difficulty when it comes to finding sufficient capital: declining rates of marriage (Pope 2002, pp. 2).

With the development of new internal policies within the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia comes an era where women have started to become more empowered. This is evidenced by the fact that nearly 54% of all university graduates within Saudi Arabia are women and that a growing percentage of them have started to focus on their own careers and the development of the family business rather than enter into a prospective marriage (Pope 2002, pp. 2).

As a result, with declining marriage rates comes a distinct decline in access to sufficient capital by bachelors since it is the intermarriage between families that often times enhances the ability of an entrepreneur to access sufficient capital to establish his own business.

Public Aid Programs

Aside from the aforementioned “traditional” methods of funding that exist within the context of the Saudi Arabian culture, there also exist other methods of funding that are more in line with what is normally seen in other countries. The first of these methods of funding is the KAFALAH fund, which is a $200 million fund that acts as a protection net against loan defaults meant to encourage local banks to lend to entrepreneurs (Country analysis report: Saudi Arabia 2011, pp. 1-68).

The reason why KAFALA fund was created in the first place was due to the fact that between 2001 to 2009 local banks experienced increasing levels of loan defaulters (Country analysis report: Saudi Arabia 2011, pp. 1-68).

One of the main reasons behind this was simply the fact that entrepreneurs at the time lacked the necessary skills and capabilities to properly market their products, develop their businesses and enhance operations which inevitably resulted in the collapse of their ventures (Country analysis report: Saudi Arabia 2011, pp. 1-68).

This was an endemic problem during that time until it was addressed by H.M. King Abdullah bin Abdul Aziz Al-Saud in the form of the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), the King Saud University (KSU) and various other educational institutions that focused on the creation, support and development of entrepreneurs within Saudi Arabia.

It was through such programs that, in the words of H.M. King Abdullah bin Abdul Aziz Al-Saud, “a new type of entrepreneur” entered into the Saudi Arabian market economy Country analysis report: Saudi Arabia 2011, pp. 1-68). Such individuals were better informed, better prepared and more likely to create fewer mistakes as compared to their predecessors.

Unfortunately, various Islamic banks were still reeling from the amount of loan defaults hence the necessity of creating stimulus funds in order to encourage lending (Apparel Retail Industry Profile: Saudi Arabia 2012, pp.1-25).

Despite this, it was noted by various Saudi entrepreneurs that such activities were still insufficient, many of whom were of the opinion that it should be the government itself that should facilitate access to funds for entrepreneurs rather than having to go through the laborious and often times unfruitful process of filing for a bank loan (Dairy Industry Profile: Saudi Arabia 2012, pp. 1-32).

One manifestation of such a necessity came in the form of the government-sponsored AlAhli Small Business Program which is a type of loan/training program enabling entrepreneurs to gain access to a variety of funding sources that are in cooperation with the National Commercial Bank while at the same time provides training courses and various types of support systems so as to enable these potential entrepreneurs to develop the necessary skills, mindsets and abilities to effectively run their fledgling businesses (Country Update 2012, pp. 1-5).

Other sources of funds also exist, which are there to address the problem of developing a funding program for young Saudi men and women that are underprivileged yet still would like to be entrepreneurs. For this particular scenario, the centennial fund exists, which provides 50,000 – 200,000 SAR in funds for particular business ventures, which is payable within 5 years.

Similar to the AlAhli Small Business Program, the Centennial fund also provides training and development services, but it also provides a mentoring program wherein experienced entrepreneurs help in guiding people who make use of the fund, through a 3 year mentoring program designed to increase the success of their business.

Other more gender-specific funds come in the form of the Prince Sultan bin Abdulaziz fund for nurturing women entrepreneurs (Country Update 2012, pp. 1-5). As its name implies, this fund focuses specifically on providing women entrepreneurs with the necessary funds and training to undertake a variety of entrepreneurial ventures.

Banking

There are several banking institutions within Saudi Arabia that do in fact provide small business loans to start-up business such as Al Rajhi Banking & Investment Corp., the Riyadh Bank, the National Commercial Bank etc. (Economic Growth: Outlook 2012, pp. 4-6).

It must be noted though that due to the high degree of loan default experienced by these banks from 2001 to 2009 the loan process often involves considerable amounts of paperwork and at times recommendations from well-established businessmen in order to gain approval for particular loans (Economic Growth: Outlook 2012, pp. 4-6).

This in effect shuts out various entrepreneurs who do not have the same amount of clout or the connections necessary to show that they can be trusted to pay back the loan. Additionally, the entrepreneurs have to go through other hurdles in form of government-sponsored programs, which act as intermediaries between the bank and the entrepreneur and acts as a safety net in case of loan default.

While this section has shown that there exists, quite literally, a plethora of funding and training opportunities for local entrepreneurs to start their own business ventures, what it does not show is that most of the funding and training opportunities are oriented towards the development of localized business opportunities and neglect to encompass a wider range of potential ventures through international markets.

The study of Mortland (2009, p 19) which examined the funding and training opportunities that are currently in place within Saudi Arabia reveals that most of the revenue derived from entrepreneurial activity within the country is primarily as a result of derived income from local markets (Mortland 2009, p. 19).

There are relatively few cases of entrepreneurs which focus on international trade with one of the reasons being that despite the presence of funding programs with associated training schemes, these programs actually encourage and focus on developing entrepreneurs to focus on developing local market (Mortland 2009, p. 19).

They propagate the notion that international business ventures are somewhat risky. This engenders a business culture that is more internally focused rather than externally adaptive. In cases where an entrepreneur is actively seeking funds to expand their business venture with a view to engaging in international trade, their loan requests are often turned down.

Banks tend to agree to loans of this nature when requested by large firms or conglomerations. This in effect shuts out small entrepreneurs from international trade, which is an important aspect of developing a local business.

Venture Capitalists within Saudi Arabia

Another of the problems faced by entrepreneurs within Saudi Arabia is the distinct lack of venture capitalists within the country. An examination of data obtained from 2010 reveals that Saudi Arabia has the lowest ranking of any G20 country in terms of venture capital funding with only $5 million being invested by venture capitalists in local businesses at the time.

Studies such as those in the Country analysis report: Saudi Arabia (2011, pp. 1 – 68 ) reveal that venture capital funding is an important facilitator of entrepreneurial activity since it acts as a method of funding “outside” of the regular methods facilitated through bank loans (Country analysis report: Saudi Arabia 2011, pp. 1-68).

With entrepreneurs and the venture capitalists sharing the risks that come with developing a particular business venture this actually results in the sharing of ideas, better internal management of operations and funds and the creation of new lines of business which helps to considerably expand the venture beyond what the entrepreneur would have been capable of doing alone.

As seen in the case of the US and UK, venture capital investments have helped to create a solid foundation for the development of numerous businesses which has actually encouraged entrepreneurial activity due to the potential that venture capitalists may choose to invest with a particular venture thus enabling it to expand based on the plans of the entrepreneur.

The lack of venture capital funding in the case of Saudi Arabia helps to explain the relatively low growth seen in the development of new entrepreneurial ventures; since an external source of capital without the accompanying financial indebtedness associated with a bank loans would have definitely encouraged the development of a sufficiently strong entrepreneurial sector within the country (Country analysis report: Saudi Arabia 2011, pp. 1-68).

One way of explaining the lack of venture capital funding can be seen in Chapter 4: Business Environment (2012, pp. 27-33) of Saudi Arabia’s business forecast report, which explored various aspects of financing within Saudi Arabia. Chapter 4: Business Environment (2012, pp. 27-33) shows that the concept of venture capital funding is relatively new within Saudi Arabia since it is a development that has only occurred within the past few decades within various other countries (Chapter 4: Business Environment 2012, pp. 27-33).

Since Saudi Arabia has developed in an entirely different way as compared to other countries such as the US due its emphasis on Shariah law in its banking and finance sector this would, of course, result in the creation of distinctly different financial instruments for funding business ventures within the country (Chapter 4: Business Environment 2012, pp. 27-33).

This is especially true when taking into consideration the fact that “family funds” are still one of the primary methods of funding a business within the country and external methods of funding not associated with either the state or a bank are still viewed with a certain degree of distrust by the local business culture.

Aside from that, most entrepreneurs within Saudi Arabia have no idea what a venture capital fund is or how it even operates, thus its level of acceptability and implementation within the context of the local economy is also rather low (Chapter 4: Business Environment 2012, pp. 27-33).

Furthermore, since the venture capital sector of the Saudi Arabian economy is still within its relative infancy this means that the roadshows, presentations, exhibits and forums normally associated with venture capital firms as seen in the context of the US and the UK are relatively absent (Chapter 4: Business Environment 2012, pp. 27-33).

This means that venture capitalists can neither show what methods of financing they can offer to entrepreneurs and neither can prospective entrepreneurs show their business ventures to venture capitalists (Chapter 4: Business Environment 2012, pp. 27-33). In the end, this creates a situation that is not at all conducive towards the development of any form of venture capital financing operation within the Saudi Arabia and explains why the amount of venture capital funding is so low within the country despite the size of its economy.

Entrepreneurs in Saudi Arabia and the local Stock Market

Aside from venture capital investments, another alternative to financing the expansion of a business venture has been through the use of the stock market. In regions such as the US, UK, and several parts of Asia, posting their company on the local stock market has been an effective method by which entrepreneurs of mid-sized corporations have been able to garner sufficient funds in a rather efficient manner.

Unfortunately, in the case of Saudi Arabia, it has been noted that despite the fact that the local stock market has actually improved by 50% as a source of funding for businesses, most of this has been primarily isolated to large scale enterprises and has barely been used to finance start-up businesses (Bradley 2005, pp. 1- 22). One of the reasons behind this is the apparent lack of a specific market that can cater for the needs of the start-up businesses.

Consequently, this prevents various Saudi entrepreneurs from accessing needed funds for expansion as compared to their counterparts within the G20 countries. From a certain perspective, it can be assumed that due to the current predilection of Saudi entrepreneurs to view the stock market as a novelty exclusively for the rich rather than alternative method of funding, resulting to a situation in which the ability of the stock market to raise capital for the entrepreneurs is greatly hampered.

Studies such as those seen in the report “Saudi Arabia business forecast report Q3 2012” (2012, pp. 1-51) have indicated that despite the 90% rise in the usage of Saudi Arabian stock market, start-up businesses continue to have a relatively low profile in it due to an insufficient amount of information regarding the process of registration, compliance and how the stock market works in general (Saudi Arabia business forecast report Q3 2012 2012, pp. 1-51)

It is based on this that the report recommends a greater degree of government assistance in the form of information campaigns so as to educate local entrepreneurs regarding the various advantages of posting their company on the stock market (Saudi Arabia business forecast report Q3 2012 2012, pp. 1-51).

Common problems that prevent Saudi entrepreneurs from obtaining finance.

Hussain and Yaqub (2010, pp. 22-28) note that as it is common when an entrepreneur wants to access loan from a financial institutions, the financial institutions subject the entrepreneur through a series of checks. This entails giving a business plan that shows the ability of the business to repay loans.

In situations in which the business plan does not depict the ability of the business to generate the revenue that can support the repayment of the loan, the request is turned down. The challenge sometimes is not in developing business plan, but rather the ability to write a good business plan that highlights the major strengths of the business.

From this section it can be seen that entrepreneurs have limited sources of capital (Hussain and Yaqub 2010, pp. 22-28). The few sources of capital that exists are meant for large-scale businesses, and not necessarily for the upcoming entrepreneurs. As it has been highlighted, most entrepreneurs obtain much-needed capital from their ‘families’.

This implies that those entrepreneurs who come from families that are not well-off find it more difficult to procure the much needed capital. Additionally, it can be inferred that the financial institutions are not very friendly to the upcoming entrepreneurs and, unless the government institutes measures to facilitate easier access to loan for the entrepreneurs, the level of growth of the private investments will continue to be low.

Methodology

Aims

Wahyuni (2012, pp. 69-80) contends that a research should have objectives. In this regard this research is supposed to consider the following objectives. Firstly, the research is supposed to investigate the sources of finance for start-up businesses in Saudi Arabia.

Furthermore, the research will also look into the bottlenecks that the entrepreneurs face when it comes to accessing sources of finance. The other objective will be to explore the various opportunities and challenges, which the entrepreneurs have to face when it comes to accessing finance from the financial institutions. In order to achieve those objectives the research will seek to address the following questions:

- Where do the successful business starters in Saudi Arabia get their capital from?

- What challenges do business start-ups encounter when financing their ventures?

- What can business start-ups do to avoid failure when sourcing out capital for their ventures?

Study Design

Given the nature of this research, the most appropriate research design that will be adopted for this paper is the qualitative research (Bansal & Corley 2012, pp. 509-513). This will enable the researcher to have open-ended questions that will help in generating of information regarding the challenges which the entrepreneurs face in Saudi Arabia.

Moreover, the use of qualitative research method enables the researcher to have fewer participants, which enable a more thorough approach to be adopted. Additionally, the information will be derived from both the primary and secondary sources. The sample participants for this study will be drawn from those individuals who have been involve in business venture in Saudi Arabia, and those who have been involved in the bank’s lending system.

This will aid in getting the necessary information regarding the challenges that Saudi entrepreneurs face in an attempt to obtain finance for their fledgling businesses. The number of participants will be limited to thirty individuals from the cities of Jeddah and Mecca. This is because qualitative research uses a limited number of participants (Bansal & Corley 2012, pp. 509-513).

Furthermore, the participants must have attempted to get financing from the financial institutions and failed. The participant must exclusively own or owned a business venture.

Another condition for the participant is that they must have complied with the regulations regarding application for financing, including submitting a business plan. It must also be acknowledged that if any information leaks to the financial institutions it might result to victimization of those participants. For this reason, the information should be kept securely so that it cannot be accessed by people who might victimize the participants.

Data Collection Process

As indicated earlier, the participants for this study will be drawn from both the entrepreneurial side and the banks’ lending system. Some of the questions which could be posed to the individuals in the banking sector will be on the number of loan requests by the entrepreneurs that were rejected and those that were accepted.

The researcher will also probe those participants so that he can have a glimpse at the reasons that led to either the cancellation or the acceptance of those loan requests. It must also be noted that the participants will be interviewed individually to enhance the confidentiality of the research. The participants will be instrumental in helping to unravel the challenges that the entrepreneurs face when it comes to accessing finance.

Additionally, the questions that will be presented to the participants will be open-ended to enhance the ability of the research to generate a lot of information. Reliability of the interview data will be tested by comparing the variables under study with similar variables from previous studies while the validity will be tested by determining the extent to which the information concurs with global financing approaches.

The interviews will be conducted on weekends to ensure that most of the participants will not be held up in their jobs, which could preclude them from attending the sessions. Another important thing which will be highlighted to the participants pertains to the confidentiality of their responses.

This will encourage the participants to be more genuine with their responses. The preferred study technique for this research will be cross-sectional. This will be informed by the fact that this study is meant to unravel information which can be used in future when carrying out research on the same issue (Wahyuni 2012, pp. 69-80).

Additionally, the time as well as the resources allocated for this research are vey limited and does not allow for the use of longitudinal technique. The data collected from this research will be analysed using data reduction techniques. This entails sifting through the data to determine those that are relevant to the issue being considered.

Reference List

Ahmad, S 2011, ‘Businesswomen in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Characteristic, growth patterns and progression in a regional context’, Equality, Diversity & Inclusion, 30, 7, pp. 610-614, Business Source Premier, EBSCOhost.

‘Apparel Retail Industry Profile: Saudi Arabia’ 2012, Apparel Retail Industry Profile: Saudi Arabia, pp. 1-25, Business Source Premier, EBSCOhost.

Bansal, P, & Corley, K 2012, ‘Publishing in AMJ -Part 7: What’s Different about Qualitative Research?’, Academy of Management Journal, pp. 509-513, June, Business Source Complete, EBSCOhost.

Baqadir, A, Patrick, F, & Burns, G 2011, ‘Addressing the skills gap in Saudi Arabia: Does vocational education address the needs of private sector employers?’, Journal Of Vocational Education & Training, 63, 4, pp. 551-561, Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost.

Bradley, J R 2005, Saudi Arabia Exposed: Inside A Kingdom In Crisis, Palgrave Macmillan, eBook Collection (EBSCOhost), EBSCOhost.

‘Chapter 2: Economic Outlook’ 2011, Saudi Arabia Business Forecast Report, 3, pp. 15-23, Business Source Complete, EBSCOhost.

‘Chapter 4: Business Environment’ 2012, Saudi Arabia Business Forecast Report, 2, pp. 27-33, Business Source Premier, EBSCOhost.

‘Constraints on Development: Small Businesses in Saudi Arabia’ 1992, Middle Eastern Studies, 28, 2, pp. 333-351, International Security & Counter Terrorism Reference Center, EBSCOhost.

‘Country analysis report: Saudi Arabia, 2011, Saudi Arabia Country Profile, pp. 1-68, Business Source Premier, EBSCOhost.

‘Country Update’ 2012, Political Risk Yearbook: Saudi Arabia Country Report, pp. U-1-U-5, Business Source Premier, EBSCOhost.

‘Dairy Industry Profile:. Saudi Arabia’ 2012, Dairy Industry Profile: Saudi Arabia, pp. 1-32, Business Source Premier, EBSCOhost.

‘Economic Growth: Outlook’ 2012, Saudi Arabia Country Monitor, pp. 4-6, Business Source Premier, EBSCOhost.

‘Economic Structure and Context: Development and Strategy’ 2012, Saudi Arabia Country Monitor, pp. 16-17, Business Source Complete, EBSCOhost.

‘Footwear Industry Profile: Saudi Arabia’ 2012, Footwear Industry Profile: Saudi Arabia, pp. 1-29, Business Source Premier, EBSCOhost.

Hussain, D, & Yaqub, M 2010, ‘Micro-entrepreneurs: Motivations Challenges and Success Factors’, 56, pp. 22-28, EconLit with Full Text, EBSCOhost.

Jacknis, N 2011, ‘Government’s Role In Facilitating An Innovative Economy’, International Journal Of Innovation Science, 3, 3, pp. 107-116, Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost.

Kayed, R, & Hassan, M 2010, ‘Islamic entrepreneurship: A case study of Saudi Arabia’, Journal Of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 15, 4, pp. 379-413, Business Source Premier, EBSCOhost.

‘Leading the way’ 2005, Banker, 155, 957, pp. 78-79, Business Source Premier, EBSCOhost.

Lindsey, U 2011, ‘Saudi Arabia’s $10-Billion Experiment Is Ready for Results. (cover story)’, Chronicle Of Higher Education, 57, 40, p. A1, MasterFILE Premier, EBSCOhost.

Mahdi, K 1998, ‘Economic development’, Economic Journal, 108, 451, pp. 1970-1971, Business Source Premier, EBSCOhost.

Mortland, S 2009, ‘A partnership fit for a King’, Crain’s Cleveland Business, 30, 5, p. 19, MasterFILE Premier, EBSCOhost.

‘Outlook for 2011-15pp. Economic policy outlook’ 2010, Country Report. Saudi Arabia, pp. 7-9, Business Source Premier, EBSCOhost.

Pope, H 2002, ‘For Saudi Women, Running a Business Is a Veiled Initiative. (cover story)’, Wall Street Journal – Eastern Edition, 2 January, MasterFILE Premier, EBSCOhost.

Robson, V 2005, ‘Business behind the veil’, MEED: Middle East Economic Digest, 49, 25, pp. 40-42, International Security & Counter Terrorism Reference Center, EBSCOhost.

‘Saudi Arabia’ 2012, Political Risk Yearbook: Saudi Arabia Country Report, pp. 1-18, Business Source Premier, EBSCOhost.

‘Saudi Arabia business forecast report Q3 2012’ 2012, Saudi Arabia Business Forecast Report, 3, pp. 1-51, Business Source Premier, EBSCOhost.

Siddiqi, M 2008, ‘Saudi Arabia: Bucking the global trend?’, Middle East, 392, p. 44, MasterFILE Premier, EBSCOhost.

S.T. 2000, ‘Striking out on their own’, MEED: Middle East Economic Digest, 44, 37, p. 42, International Security & Counter Terrorism Reference Center, EBSCOhost.

Wahyuni, D 2012, ‘The Research Design Maze: Understanding Paradigms, Cases, Methods and Methodologies’, Journal Of Applied Management Accounting Research, 10, 1, pp. 69-80, Business Source Complete, EBSCOhost.

Zahra, S, & Wright, M 2011, ‘Entrepreneurship’s Next Act’, Academy Of Management Perspectives, 25, 4, pp. 67-83, Business Source Premier, EBSCOhost.