Introduction

The persuasive power of corporate social responsibility (CSR) comes from the notion that it helps members of an organisation become good actors and take part in morally worthy activities. It makes them feel that they are working towards being the ideal persons in their communities. It also helps employees become better at performing their duties.

Nevertheless, most companies fail to achieve the goal of appropriate employee and other stakeholder engagement because they take on technological control bluntly. Rather than allow staffs and stakeholders to have relationships that are evolving and incremental, management in such companies restricts itself to the controlling role (Dai, Ng & Tang 2013). It issues guidelines on what to do and procedures to follow.

It also offers policies to determine specific behaviour and causes CSR activities to happen only in circumstances that provide all the necessary requirements, according to the laid out parameters (Costas & Karreman 2013).

Statement of the research problem

Stakeholder engagement is critical for CSR success, yet many businesses continue to use technologies for CSR based on the best-practice rationale, rather than relying on the actual needs of their communities. It is essential to know the exact challenges that a specific firm faces to change the overall understanding of best practices and to inform better decision making concerning the management of CSR in the future.

Background/Rationale of the study

CSR traces back to ancient times when authorities introduced different rules to ensure that businesses pay taxes to fund activities of government. Over time, social issues have arisen from insignificance to become major parts of community concern about the conduct of businesses (Kytle & Ruggie 2005).

The theory of CSR shows firms moving from an obligatory position of managing their responsibilities to stakeholders to voluntary positions where they initiate programs for sustainability. Nevertheless, the inclusion of technology development as part of various business activities of firms has only meant that technological challenges associated with general organisational performance also affect CSR management.

Statement of the research questions

R1. What are the main motivating factors for managing CSR?

R2. How are the motivations for CSR different at the firm level and at the industry level?

R3. What are some of the technology-related challenges that firms face when managing CSR?

Objectives of the research

The research seeks to explain the main technological challenges that firms face when managing their CSR activities. Therefore, the research pursues existing notions of CSR implementation in both theory and practice to highlight trends and bring out any notable challenge observations concerning this objective.

Research gaps

In the consulted literature, much of the evidence points out to general implementation of technology as a business activity and not exactly as part of CSR. Furthermore, much of the available scholarly material associates technology as a subject within CSR with the management of CSR in technology companies. There are limited papers dealing with the specific topic of technological challenges for managing CSR.

Limitations of the study

The main concerns for the paper were on finding out technological challenges, but the lack of primary data in the case analysis compelled the researcher to rely on materials that would have been collected with a different aim.

Thus, the accuracy of the conclusion of this study is hampered by the broadness of the literature consulted. Opinions of theoretical interpretations in the consulted papers may have also affected the recommendations presented in this research.

Organisation of the paper

This paper begins with an executive summary of the research and then highlights its main objectives, background, and limitations in the first section under introduction.

Section two is a literature review that combines both practical and theoretic literature on the subject, while the third section explains the method used to collect data for the research and analyse it. Finally, the paper offers an analysis of the Emirates Airlines case and concludes with recommendations for practitioners.

Literature review

According to Dai, Ng, and Tang (2013), CSR activities in firms could be categorized as either responsive or strategic. Depending on the underlying nature of CSR in a particular firm, relevant or best practice approach may or may not be suitable for effective realisation of CSR objectives.

At the same time, there are boundary systems and diagnostic uses of budgets aimed to provide a structure under which all aspects of CSR would fall into.

However, in the strategic form of CSR, a structural limit is not visible around the firm’s activities, as they do with the alternative form. Here, the focus rests on the operationalizing of responsive agendas that rely on the overall belief system or interactive uses of management in the firm.

The research by Dai, Ng and Tang (2013) agrees to the fact that CSR is significant for sustainable development of a firm. Moreover, it is critical for harmonious co-existence of society as a whole and the different corporate elements operating within it. Nevertheless, the researchers sought to find out how firms are able to realize both the objectives of responsive CSR and those of strategic CSR.

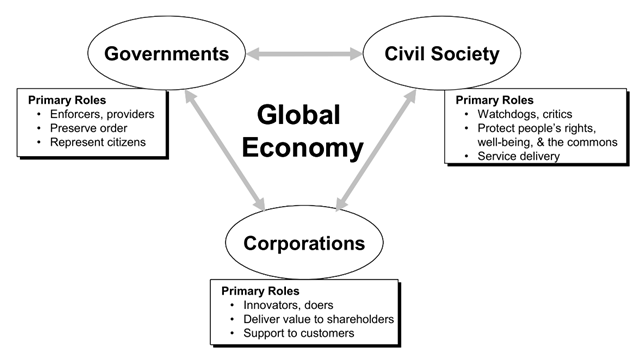

With globalization, business leaders have to grapple with environmental variables that are different from what they are used to at national and local levels. They face an increased amount of uncertainty and they can only lead their organisations effectively when they properly understand the dynamics of the global operating environment (Kytle & Ruggie 2005).

In the realm of CSR management, the global context brings networked operations, value chain, and the global economy into the picture. It also presents challenges and opportunities for empowering global stakeholders and throughout the interaction of these factors, there exists a dynamic tension among stakeholders, which CSR would aim to eliminate or minimize (Kytle & Ruggie 2005).

Figure 1: Global operating environment for firms (source: author)

The business world continues to experience constant shifting market realities, partly due to technological changes. At the same time, technology is also becoming a critical factor for organisational success.

Meanwhile, the new media technology has allowed stakeholders to not only learn about CSR initiatives that companies undertake, but also the belief system of companies and their overall attitudes towards society. It has raised the bar for stakeholder engagement (Nwagbara & Reid 2013).

The research done by Costas and Karreman (2013) brings out a challenge that employees face when they try to have their organisations embraces various forms of social responsibility. A problem with employees when it comes to CSR is that they are at the mercy of the management.

If the management of the organisation has no intentions of involving employees in coming up with CSR strategies, then they will almost feel detached from the whole exercise. It is not surprising to find employees being doubtful about the impact of CSR to the people they work with, simply because they hold disbelief of their management strategies.

Eventually employees learn to accept things as they are since they cannot change them. A problem with this approach in the present age of social media technology is that the employee can end up branding the whole CSR exercise as just PR, which then ends up being taken lightly by the target community (Costas & Karreman 2013).

As Bertels and Peloza (2008) report, management executives are being encouraged now more than ever to have CSR as part of their business vision and brand management. This calls for the integration of CSR into the normal business practices of a firm and the use of management technologies to monitor the progress of CSR.

Issues such as performance benchmarks, total quality control, and their various implementation software tools are now critical to the success of CSR. Moreover, firms are not merely implementing technologies for measurement and application of CSR strategies because they see it is a good fit for their strategy only. They are also doing so because it has become part of a competitiveness threshold.

When CSR becomes a core practice for a corporate strategy, it becomes the basis of brand equity and the main driver for innovation and technology management, as well as organisational learning (Luetkenhorst 2004).

As global firms integrate their value chains to realize widespread CSR effects and to become more responsible for the entire process of producing their products, they also become development partners for developing and upgrading country SMEs (Faisal 2010).

The integration allows the smaller companies to upgrade their technology and improve their management practices to comply or match the same solutions used by the global value chain leader (Luetkenhorst 2004).

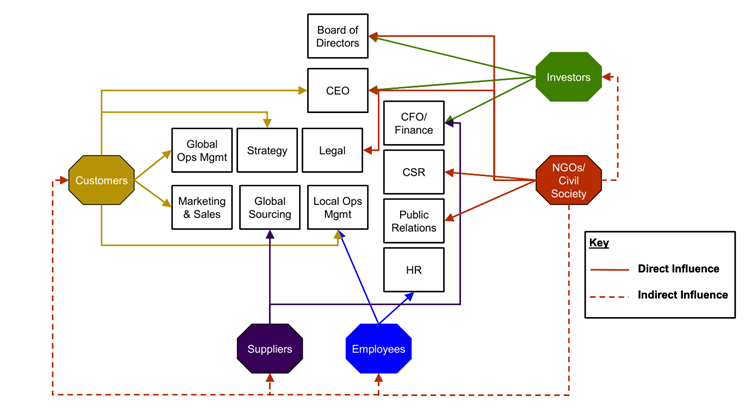

Global firms are increasingly realizing that they have to manage stakeholder engagement well and internationalize the information they collect about social risk. Technology is critical in the management of stakeholder involvement, which has become a critical component of CSR (Kytle & Ruggie 2005).

Figure 2: CSR mapping of risk entry points (Kytle & Ruggie 2005)

Tan and Tan (2012) highlight the fact that digital communications industries are sites of CSR conflicts. The challenges they face will eventually be felt by other industries because they are one of the fastest growing industries. This would be in line with the observations made by Bertels and Peloza (2008).

The rapid rise in internet users only means that the level of stakeholder engagement that companies have to conduct has increased incredibly. According to Chang et al. (2014), social structures form when humans interact with technology alone or when they make technology-mediated human-to-human interactions. Corporations can move further by forming collaborations with community groups and public authorities.

Increased scrutiny is making companies more careful with their supplier guidelines, which include social and environmental obligations and supplier codes of conduct. Technology is becoming a differentiating factor among firms that seek to eliminate supply chain inefficiencies and maintain sustainable procurement practices, which fall well into CSR objectives of ensuring social and environmental compliance (Joseph 2009).

As companies focus on their value chains, they increasingly encounter problems of communication between design and manufacturing divisions often located in different geographic locations (Cruz 2013). However, through product lifecycle management, firms are able to use business and information strategy that lets them identify and source from firms that follow sustainable practices.

Logistics is another avenue that is a core business activity, which also falls into the grand scheme of CSR (Nikolaou, Evangelinos & Allan 2013).

However, firms face challenges in acquiring and using logistic software applications that can enhance their CSR strategies by bringing tangible benefits on the reduction of environmental harm, as well as the reduction of cost to make CSR viable within the organisation (Ferguson 2011).

The most crucial theories emerging from the literature review mainly relate to the definition of CSR, which ends up affecting the scope of its implementation.

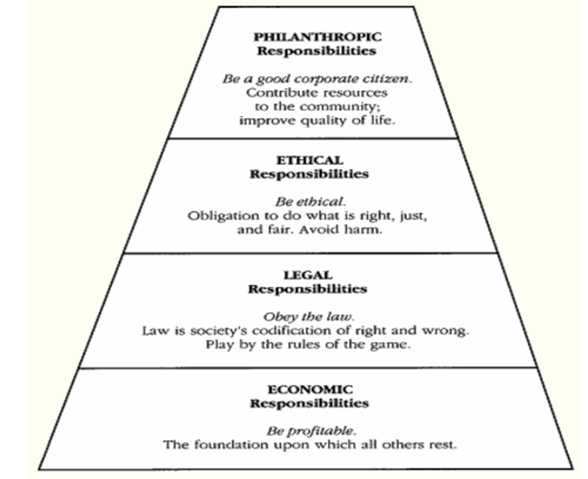

One of them is the view of CSR as an open and transparent business practice using ethical values and respect for employees and stakeholders, as well as the environment (Sharma & Kiran 2013). In addition, there is the widely accepted theory of CSR is the pyramid of corporate social responsibility theory first formulated in 1991 (Carroll 1991).

Figure 3: Pyramid of CSR (Carroll 1991)

At the lowest level of the pyramid, organisations aim to be profitable. Thus, they pursue economic responsibility, as far as CSR is concerned. However, they embrace legal responsibility when they move on to the next level because they ought to obey the law as moral corporate citizens.

They play by the rules. Moving on to a higher level, they now become ethically responsible and seek to appear as ethical in all their dealings. Here, the obligation is to do what is right. At the highest levels of CSR, the firm becomes a good corporate citizen. It initiates actions without necessarily being driven by the need to comply. This is termed as philanthropic responsibility in the pyramid presented by Carroll (1991).

Methodology

The method used for the research was qualitative. The researcher also relied on secondary literature and there was no collection of primary data. The chosen study area was narrowed down to the subject of CSR, with the main focus being on the motivations for implementing and managing various CSR activities without firms and industry.

The theoretical underpinnings of the subject informed the review, whose aim was to highlight the challenges that can occur theoretically and those that arise in practice, which mainly concern technology in its acquisition or implementation for the realization of CSR objectives.

Care was observed to only consult secondary sources that are academic, unless the information obtained would help in the case analysis. The case analysis was to help bring out practical challenges in an enterprise. The enterprise chosen was Emirates Airlines.

Analysis

The Emirates Airlines believes that its business ethics is integral to its continued success. The company focuses on employees as the biggest contribution to its sustainability objectives. Even as the company looks after its 62,000 employees, it still retains focus on being profitable and embraces technologies that allow it to achieve both employee welfare advancement, product and, service innovation and social or ecological sustainability.

For example, the Emirates Airlines committed billions of dollars in acquiring the most advanced aircrafts. The airline is also able to realize huge fuel cost savings and significantly cut emissions, thus reducing the negative environmental impact of its airlines. On the ground, the company is deeply involved in the management of natural and cultural heritage.

The company has initiatives for wildlife protection in the UAE and Australia (The Emirates Group 2014). The company also runs the Emirate Airline Foundation that donates to major projects around the world (Emirates 2009).

The Emirates are one of the fastest growing full service airlines in the world and its global presence exposes it to CSR scrutiny from various stakeholder groups (O’Connell 2011). Its motivations for corporate social responsibility at the level of the firm include external influences and sector specific influences.

Like any other company in the airline industry, the Emirates Airline has to adopt practices from its rivals to ensure that it retains its market share. At the same time, it has to constantly strive to have distinctive advantages in its business to realize its profitability and growth objectives. Unfortunately, the task of criticizing CSR is easy, as the effects of a firm’s actions to society and the environment are apparent.

The interpretation of financial benefits, competitive advantages, image enhancement, stakeholder pressures and desire to delay or avoid regulatory action are all potential motivations and catalyst for the CSR strategy at Emirates Airlines. Nevertheless, none of the visible initiatives of the company concerning its responsibility practices strategic.

Most of them seem to only respond to industry best practices and a mimic of what the competition is doing. There are visible through internal leadership, culture, and the financial position of the company.

They are also notable in the pledges made by the firm to take a course of action, the responsibility taken for its action, the level of involvement with environmental and social issues, and the dedication to improving firm’s performance. Among these, the Emirates Airlines demonstrates a high degree of taking responsibility for its actions, which is a reactionary approach, and being committed to improving its performance.

One of the challenges that the Emirates Airlines faces as it grows is dumping of capacity accusation from regional airlines. Many of the rival airlines are appealing to their respective governments to prevent the airline from abusing its strong cash position to double flights in routes that are not very populous.

The main argument against the Emirates is that it relies on government subsidies; thus, it is not an equal competitor to its rivals that are strictly commercial operators.

The airline has an advantage position over its rivals because it accesses affordable fuel at its Dubai hub and the cost of human resources at the city is lower that other major cities around the world like the UK where its rivals operate from. At the same time, airport charges in the Dubai hub are also a source of competitive advantage for the airline. As a result, the organisation does not face a lot of business challenges. With a young airline fleet, maintenance costs are fairly low and environmental concerns are also low.

However, the airline will have to respond to concerns about airline fuel efficiency and disposal of old inventory when it has finally upgraded a majority of its current fleet. The lack of considerable technological challenges for managing CSR allows the Emirates to allocate a lion share of its marketing budget to sponsorships that increase its brand visibility (O’Connell 2011).

For the Emirates Airlines, technology development is one of the support activities that help the airline to become competitive (Pinnington 2010).

However, when the business environment is not very promising, especially when there is a global recession, the airline is forced to cut back on its technological expenditure, especially for planned upgrades of its systems and fleets. It is expected that the cuts also extend to other operational areas, as well and would halt the scope of CSR outreach endeavours significantly.

Conclusion and recommendations

CSR continues to evolve as a field and many organisations are realizing that they do not just have to respond to regulations and best practices about their responsibilities. As early adopters of voluntary CSR continue to gain competitive advantages, they will keep on influencing their respective industry norms. The Emirates Airline case shows that for some companies, deep engagement in CSR as a separate activity is not viable.

However, success levels are reachable when the same initiative forms part of core business practices. Nevertheless, the integration of CSR into core business practices exposes initiative to the technological challenges that affect organisational operations, such as lack of funds, lack of expertise, and employee resistance.

Meanwhile, technological advances in isolation also act as factors that hamper or support the management of CSR. In this regard, the researcher proposes that future studies should compare the practice of various firms in the same sector and across sectors and specifically collect primary data for understanding technological challenges of managing CSR. In addition, practitioners should go for responsive CSR implementation.

Reference List

Bertels, S & Peloza, J 2008, ‘Running just to stand still? Managing CSR reputation in an era of ratcheting expectations’, Corporate Reputation Review, vol 11, no. 1, pp. 56-72.

Carroll, AB 1991, ‘The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders’, Business Horizons, vol 34, pp. 39-48.

Chang, Y-J, Chen, Y-R, Wang, FT-Y, Chen, S-F & Liao, R-H 2014, ‘Enriching service learning by its diversity: Combining university service learning and corporate social responsibility to help the NGOs adapt technology to their needs’, Systemic Practice and Action Research, vol 27, no. 2, pp. 185-193.

Costas, J & Karreman, D 2013, ‘Conscience as control – managing employees through CSR’, Organization, vol 20, no. 3, pp. 394-415.

Cruz, JM 2013, ‘Modeling the relationship of globalized supply chains and corporate social responsibility’, Journal of Clearner Production, vol 56, pp. 73-85.

Dai, NT, Ng, A & Tang, G 2013, ‘Corporate social responsibility and innovation in management accounting’, CIMA, vol 9, no. 1, pp. 1-10.

Emirates 2009, ‘Support’, The Emirates Airline Foundation, February 2009.

Faisal, MN 2010, ‘Analysing the barriers to corporate social responsibility in supply chains: an interpretive structural modelling approach’, International Journal of Logistics: Research and Applications, vol 13, no. 3, pp. 179-195.

Ferguson, D 2011, ‘CSR in Asian logistics: operationalisation within DHL (Thailand)’, Journal of Management Development, vol 30, no. 10, pp. 985-999.

Joseph, G 2009, ‘Mapping, measurement and alighnment of strategy using the balanced scorecard: The Tata steel case’, Accounting Education: An International Journal, vol 18, no. 2, pp. 117-130.

Kytle, B & Ruggie, JG 2005, ‘Corporate social responsibility as risk management: A model for multinationals’, Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative Working Paper, Johm F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, 10, Cambridge, MA.

Luetkenhorst, W 2004, ‘Corporate social responsibility and the development agenda’, Intereconomics, vol 39, no. 3, pp. 157-166.

Nikolaou, LE, Evangelinos, KL & Allan, S 2013, ‘A reverse logistics social responsibilty evaluation framework based on the triple bottom line approach’, Journal of Cleaner Production, vol 56, no. 1, pp. 173-184.

Nwagbara, U & Reid, P 2013, ‘Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and management trends: Changing times and changing strategies’, Economic Insights – Trends and Challenges, vol 11, no. LXV, pp. 12-19.

O’Connell, JF 2011, ‘The rise of the Arabian Gulf carriers: An insight into the business model of Emirates Airline’, Journal of Air Transport Management, vol 17, no. 6, pp. 339-346.

Pinnington, A 2010, Strategic management and IHRM, Sage Publications.

Sharma, A & Kiran, R 2013, ‘Corporate social responsibility: Driving forces and challenges’, International Journal of Business Research and Development, vol 2, no. 1, pp. 18-27.

Tan, J & Tan, AE 2012, ‘Business under threat, technology under threat, ethics under fire: The experience of Google in China’, Journal of Business Ethics, vol 110, no. 4, pp. 469-479.

The Emirates Group 2014, Responsibility, <http://www.theemiratesgroup.com/>.