Introduction

Siamangs are diurnal, active and sociable nonhuman primates. They live in vast areas in the wild and need space to move and brachiate. They also live in families. Notably, these animals can also coexist with other species (Pearson, Davis & Litchfield, 2010). Clearly, in zoos, these animals are placed in spaces which have similar characteristics with the usual habitat of the apes. For instance, in San Diego zoo, there are specific facilities which imitate the environment siamangs live in.

These apes have the opportunity to brachiate and move a lot. At that, siamangs are placed with orangutans and this does not lead to aggression as two species seem to be friendly to each other. However, there is a common viewpoint that animals do not feel comfortable in zoos and visitors’ attention and limited space makes them act differently (Smith & Kuhar, 2010). Therefore, it is possible to formulate the hypothesis as follows: in the daytime, siamangs will be less active and will spend most of time eating and resting due to lack of space.

Materials and Methods

The present study is based on observation of three siamangs in San Diego zoo with the help of the web camera. Each twenty seconds behavior of siamangs was scanned. The observation lasted thirty minutes. Since it was difficult to differentiate among the individuals, behavioral patterns of each primate were calculated for the entire group. In other words, the percentage of behavioral patterns revealed in the result section is a sum total of each individual’s patterns.

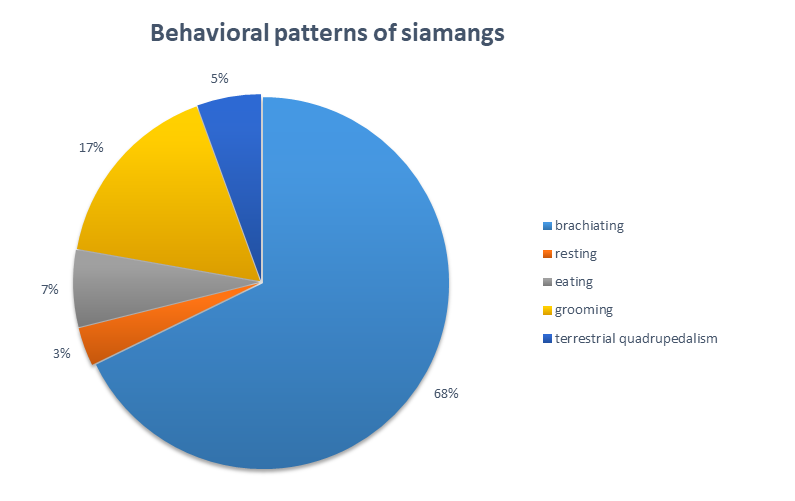

The following behavioral patterns were scanned: brachiating, resting, eating, grooming, and terrestrial quadrupedalism. Notably, the siamangs often acted similarly and were engaged in group activities (brachiating or grooming). It is necessary to note that it was sometimes difficult to follow the animals as they were moving quite quickly and the quality of the picture was not always perfect due to technical issues.

Results

According to the data obtained, siamangs spent most of their time (68%) brachiating (see figure 1). They spent less time grooming (17%), eating (7%), moving on the ground (6%), and resting (3%). It is necessary to add that due to technical difficulties the numbers are approximate as it was sometimes difficult to follow each individual. As has been mentioned above, the behavioral patterns are somewhat generalized.

Discussion

Observation implemented resulted in quite unexpected data. The results of the research disprove the hypothesis as it was assumed that siamangs would be less active in the zoo due to visitor’s attention and limited territory. Siamangs were expected to be more passive due to the stress associated with zoo conditions.

On the contrary, the subjects of the study were very active and spent most of their time (68%) brachiating. This finding goes in line with the result of another research where Pearson et al. (2010) focused on siamangs’ behavior in the zoo. The researchers note that the primates are very active and do not mind visitors’ attention. The primates prefer brachiating and do not rest for a long time during daytime according to Pearson et al. (2010).

However, Pearson et al. (2010) also admit that sometimes siamangs moved to distant areas to avoid people’s attention. It is necessary to note that the present study does not focus on the correlation between visitors and behavior of siamangs as there was no opportunity to observe the number of people around the ape’s area.

Nonetheless, it is possible to assume that there were some visitors as the observation took place in the daytime. It is necessary to add that siamangs were very acrobatic while brachiating. They seem to focus on their own affairs and ignore people around them. Notably, Smith and Kuhar (2010) claim that primates tend to tolerate well visitors’ attendance in zoos. These primates also tend to tolerate the limited space according to the researchers (Smith & Kuhar, 2010). Therefore, it is possible to note that siamangs in the San Diego zoo are no exception.

Grooming is another activity performed by siamangs quite often (17%). This can be explained by the fact that siamangs are very sociable and often live in families (Liebal, Pika & Tomasello, 2004). Researchers stress that grooming is a way to reveal care as well as dominance (Liebal et al., 2004). The animals’ care about each other can also be an explanation for siamangs’ tolerance of the limited space. Thus, siamangs do not feel frustrated or they do not need a larger area as they have their family and can focus on their offspring.

Interestingly, Liebal et al. (2004) consider facial expressions and gestures in siamangs, which also suggest that these animals are attached to each other. Notably, the researchers report about 31 signals of social communication through gestures and facial expressions (Liebal et al., 2004). This suggests that communication is very important for siamangs and this aspect needs in-depth analysis. The present study does not include analysis of facial expressions as it was difficult to calculate precise number of such instances though many cases of this kind of communication was noted.

When it comes to eating, the number of times the primates ate is quite small (7%). This finding could be regarded as certain support to the hypothesis. However, the fact that siamangs spend little time eating does not mean the primates refuse food. It may mean that they were fed (the food was brought earlier) earlier and were not hungry. It is also possible to add that the period of observation was quite short and it could be the reason why instances of eating were quite rare.

Furthermore, the instances of terrestrial quadrupedalism are infrequent as well (only 6%). Siamangs prefer brachiating and being in the trees (Pearson et al., 2010). Since siamangs are arboreal primates, this finding was anticipated. Nevertheless, it is possible to add that Pearson at al. (2010) state that siamangs spend 50% of their days in the trees.

This study’s results suggest that siamangs spend over 70% in the trees (or facilities imitating trees in zoos). Again, this may be due to the limited time of observation. It could be the period of the highest activity or simply a period of games and observation in other parts of the day could lead to different data and conclusions.

Finally, siamangs were resting only 6% of the time observed. Again, this disproves the hypothesis as they do not spend their time passively. An animal that badly tolerates conditions in a zoo is often passive. Thus, it is possible to conclude that siamangs were active as the were not stressed and felt comfortable. In other words, the primates behaved in a way they would act in the wild.

Conclusions

To sum up, it is possible to state that the hypothesis of the present study was disproved. Siamangs tolerate life in the zoo and behave in a natural way. These animals are very active and sociable in the wild as well as in the zoo. They spend most of their time brachiating and they also pay a lot of attention to each other.

It is necessary to add that the present research is associated with a number of limitations. In the first place, the period of observation was quite short and the animals’ behavior could be different at another part of the day. Apart from this, it was impossible to evaluate the number of visitors, and people around the ape’s area could affect the way siamangs behaved. Finally, there were some technical issues and it was difficult to follow the animals and note all their movements.

Therefore, the present research can be the first step in analysis of siamangs’ behavior in a zoo setting. In the first place, it is necessary to extend the period of observation. It can be one day or it can be several hours at different times of day during a week. It is necessary to observe siamangs’ behavior during different parts of day to have data that are more comprehensive. Besides, it is possible to extend the list of behavioral patterns and include gestures and facial expressions.

It is also necessary to include another variable to the study. It is important to evaluate correlation between siamangs’ behavior and the number of visitors. These data can help understand whether siamangs feel comfortable in zoo settings and behave in a natural way.

Reference List

Liebal, K., Pika, S., & Tomasello, M. (2004). Social communication in siamangs (Symphalangus syndactylus): Use of gestures and facial expressions. Primates, 45(1), 41-57.

Pearson, E.L., Davis, J.M., & Litchfield, C.A. (2010). A case study of orangutan and siamang behavior within a mixed-species zoo exhibit. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 13(1), 330-346.

Smith, K.N., & Kuhar, C.W. (2010). Siamangs (Hylobates syndactylus) and white-cheeked gibbons (Hylobates leucogenys) show few behavioral differences related to zoo attendance. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 13(1), 154-163.