Abstract

This paper delves into the issue of mosquito control strategies through an examination of present-day issues and evaluates the literature on administrative, technical, regulatory, and professional practices involved in reducing exposure to mosquito-borne diseases and how are their strategies tailored to specific contexts. The main issue that this paper will attempt to address is the development of a more sustainable framework for the control of mosquitoes and their respective health threats. To accomplish this, an examination will be conducted with stakeholders involved in public health and mosquito control at local, state, and national levels that can comment on their activities with authority. A list of interview questions will be utilized that is tailored to different groups of stakeholders with the intent of eliciting data that answer my research questions.

Through this process, the researcher will be able to examine the current processes that are in use within such organizations and determine whether they are efficient, forward-thinking, and can properly address the myriad issues involved in proper mosquito control when compared to current literature on the subject. It is expected that through this paper a better understanding of the current mosquito control processes within L.A. and Texas will be developed resulting in the creation of better practices as a direct result of the investigation. Before proceeding, it should be noted that one of the main issues that the researcher had with the project was that due to the method of investigation (i.e. structured interviews) there were few means by which the answers given by the individual participants could be verified within a specific amount of time. To resolve this issue, the researcher analyzed the interview results with the available literature on the subject to ensure that the information given was accurate.

Introduction

As population centers continue to grow within the U.S., the issue of disease prevention is becoming an increasingly prevalent issue within the past few years. Outbreaks of the West Nile virus in the U.S. coupled with the occurrence of Dengue fever in Florida and Hawaii as well as an assortment of other mosquito-borne illnesses have shown the necessity of developing planning frameworks for government agencies such as the Center for Disease Control (CDC) to mitigate and control the outbreak of mosquitoes in and around populated urban environments (AbuBakar, 1-9). The main problem of urban centers is the fact that the level of population density with nearly 1,000 people per city block within the cities of Los Angeles and Houston alone results in a greater likelihood for the spread of infection (Ferguson, 3142-3151).

Female mosquitoes do not need to fly as far as to extract blood from multiple hosts thereby facilitating the spread of diseases within a relatively short amount of time (Vezzani, 299-313). Coupled with the proximity of modern-day cities to large bodies of water and the ubiquitous nature of salient pools of water within many urban locations (i.e. rooftops, alleyways, backyards, derelict warehouses, etc.) this has created a “perfect storm” for the proliferation of mosquitoes resulting in the need to address such concerns with a planning framework that can be utilized by government agencies to neutralize such a threat to public safety (Lydy, 5817-5822).

Evidence of this can be seen from the following chart which compares identified areas of mosquito blooms (i.e. sudden increases in the mosquito population) between Los Angeles, Kansas City, and Pharr, Texas. It was shown that urban areas that were susceptible to heavy rainfall had a greater predilection towards large mosquito blooms as compared to urban areas that were situated in hotter and dryer environments.

As can be seen, L.A. and Pharr which are situated near large bodies of water and experienced higher levels of mosquito blooms as compared to Kansas City. On the other hand, it should be noted that when comparing the data results of mosquito blooms from the indicated areas with rural locations within the same state, it was noted that there were relatively fewer cases of these blooms that occur.

From the graph above, it can be seen that rural locations had a lower propensity for the development of mosquito blooms despite the lack of sufficient monitoring and direct government intervention. Williams and Rau (2011) postulate that the development of urban environments and the various artificial processes that are utilized to reduce the mosquito population are actually to blame for such a disparity since it in effect eliminates the natural processes that would normally control the mosquito population in the form of local predators and hostile environments for mosquito larva.

It is based on this that this paper will explore the administrative, technical, regulatory, and professional practices involved in reducing exposure to mosquito-borne diseases within the context of the urban populations of Houston, Texas, and Los Angeles, California. This will be accomplished through an examination of relevant literature and the opinions of officials from local government agencies that are responsible for preventing the spread of mosquito-borne diseases. It is expected that through such an examination the researcher will be able to determine if the current methods utilized by such agencies are inadequate and if so develop a method to address the perceived problems.

Background of the Study

From the study of Williams and Rau (2011), it was noted that mosquitoes transmit diseases to an estimated 700 to 800 million people a year across the U.S., Europe, Asia, and various other regions in the world (Williams and Rau, 195-199). This has resulted in millions of deaths as a direct result of diseases and parasites as well as billions of dollars in healthcare costs. Weill (2011) even notes that one of the most common mistaken assumptions by the general public at the present is that mosquitoes are generally a rural problem with urban centers supposedly being relatively “safe” given the assortment of ventilation systems and preventive measures that are supposedly in place (Weill, 286-298). Such an assumption could not be farther from the truth given that out of the 700 to 800 million cases of mosquito-borne infections that are reported each year, nearly 60% to 70 percent of them are from urban centers (Guiyun, 1-8).

The reason behind this is quite simple; the population density of many urban centers at the present ensures that mosquitoes can infect multiple individuals within a relatively short period (Beier, 3-11). This is in contrast to rural locations where the low population densities result in fewer cases of infections given the time and distance it would require to infect multiple individuals (Beier, 1223-1234). Not only that, rural populations have natural protective measures in place within the local environment (i.e. birds, lizards, reptiles, fish, etc.) which help to naturally control the mosquito population resulting in the relatively fewer cases they experience each year (Beier, 1223-1234). Urban environments on the other hand do not have such a ubiquitous method of protection and instead have to rely on public services to deal with the spread of disease via mosquitoes (Beier, 61-71).

Within the U.S. the Center for Disease Control (CDC) and local government agencies are tasked with implementing specific planning frameworks to address the mosquito issue in a manner that helps to reduce the number of cases per year (Beier, 61-71). The inherent problem though with mosquito control is that climate variation combined with regional nuances (i.e. natural land formations, proximity to large bodies of water that are ideal mosquito breeding ground, and other such factors) leads to the necessity of developing region-specific plans for dealing with mosquito problems (Ezanno, 7-17). Das (2003) even points out that one of the main problems with urban planning at the present is that many of the major cities within the U.S. such as L.A., Miami, San Diego, and Houston are located near large bodies of water which are prime locations for mosquito breeding (Das, 3).

Combined with their respective urban densities and the development of stagnant bodies of water within rooftops, backyards, derelict industrial complexes, and other such areas which are prone to occur within most urban locations, cities can be considered ideal breeding grounds for mosquitoes (Skovmand, 2361-2371). Not only that, studies such as those by Urbanelli (2007) show that the females of many mosquito species can live for weeks or up to a month at a time and can traverse distances of 20 miles or greater within their life spans (Urbanelli, 682-691). This means that even if an urban environment is not directly beside a large body of water it can still be impacted by mosquito populations (Paskewitz, 49-57).

Objectives

This paper will attempt to answer the following questions:

- What are the administrative, technical, regulatory, and professional practices involved in reducing exposure to mosquito-borne diseases, and how are their strategies tailored to specific contexts as Best Management Practices?

- How do different levels of government respond to controlling and regulating exposure to mosquito-borne disease?

- How do budgets for mosquito control respond to urban economic recession?

- How may climate change affect exposure to mosquito-borne disease and how can communities aptly respond to an altered threat context?

Scope and Limitations

The independent variable in this study consists of the academic literature that will be gathered by the researcher for the literature review while the dependent variable will consist of the responses gained from the officials in mosquito control or public health agencies that will be recruited for this study. It is anticipated that through a correlation between the literature on mosquitoes and the urban environment and the responses of the various officials and personnel that will be interviewed, the researcher will in effect be able to make a logical connection regarding the current effectiveness of present-day planning frameworks for controlling mosquitoes within the cities of L.A. and Houston.

Overall, the data collection process is expected to be uneventful; however, some challenges may be present in collecting data involving planning frameworks and current agency practices that are to be utilized in this study.

Such issues though can be resolved through access to online academic resources such as EBSCO hub, Academic Search Premier, Master FILE Premier, Newspaper Source Plus, and AP News Monitor Collection. Other databases consulted for this topic include Emerald Insight, Academic OneFile, Expanded Academic ASAP, General OneFile, Global Issues in Context, Newsstand, Opposing Views in Context, popular magazines as well as other such online databases which should have the necessary information. Relevant books were also included in the review. Furthermore, websites such as CDPH.ca.gov and mosquitoes.org have several online articles that contain snippets of information that should be able to help steer the study towards acquiring the necessary sources needed to justify asserted arguments. It must be noted that the time constraint for this particular study only allows structured interviews with an unrepresentative number of people, and also a limited amount of flexibility when conducting the interview.

The main weakness of this study is in its reliance on interview results as the primary source of data to determine the general opinion of officials in mosquito control or public health agencies. There is always the possibility that the responses could be false or that the official in question does not know anything at all about the nuances of planning frameworks as indicated by the researcher. While this can be resolved by backing up the data with relevant literature, it still presents itself as a problem that cannot be easily remedied.

Significance of the Study

Mosquitoes and their irritating bite represent a public nuisance in and of itself but a greater concern is their role as a disease vector. Diseases such as West Nile Virus, Dengue Fever, Eastern Equine Encephalitis, St. Louis Encephalitis, and Dog Heartworm are transmitted by a variety of mosquito species in North America. The nuisance and threat of disease posed by mosquitoes inhibit the full enjoyment of outdoor recreation and public spaces.

Aggressive use of DDT and other synthetic pesticides was until recently viewed as a silver bullet in combating mosquito-borne disease. Massive and comprehensive spraying efforts following WWII all but eradicated malaria in Western Europe and North America. Despite the effectiveness of DDT, what became clear in the aftermath was that such policies also carried severe secondary effects upon non-target species, water quality, and public health.

Since the 1970s, efforts have instead focused on limiting mosquito contact with humans to levels that can be considered tolerable. This strategy of Integrated Mosquito Management focuses first on source prevention by inhibiting the growth of aquatic larvae by physical, biological, or chemical remediation. Sophisticated mosquito control programs maintain regular monitoring programs to estimate changes in populations of certain species and incidence of any carrying disease. Many communities simply rely on clinical cases of human infection as an impetus to investigate further or escalate intervention in a largely reactive manner. Because mosquitoes can exploit features of the urban landscape and urban ecosystem, and because this landscape and its ecosystem are largely shaped by the way we design and plan them, planners have an opportunity to structurally obviate the presence of a significant fraction of those mosquitoes. With globalization and the ease by which people may travel long distances, infectious diseases now spread much faster than they have in the past.

The arrival of West Nile Virus in the U.S. and recent outbreaks of Dengue in Florida and Hawaii only elevate the need for attention. Similarly, as witnessed with the recent introduction of the Asian Tiger mosquito, non-native disease vectors alter the dynamic of our ecosystem only to present new challenges. While exotic diseases such as Malaria, Yellow Fever, and Chikungunya are endemic in countries outside the U.S., there is a very real threat that an infected host traveler can inadvertently pass the disease to viable mosquito vectors in the U.S. and propagate an epidemic cycle.

Finally, much has been said about the role that climate change may play in altering the geographic range and habitat opportunity for mosquito broods. While it would be beyond the scope of this research to predict how mosquitoes will respond to an altered ecology congruent with climate change, it is nonetheless important to gauge how public health and mosquito control authorities are prepared for such contingencies.

Literature Review

Introduction to Literature

This section reviews and evaluates the literature on administrative, technical, regulatory, and professional practices involved in reducing exposure to mosquito-borne diseases and how are their strategies tailored to specific contexts. Through this section, readers will be able to better understand how different levels of government respond to controlling and regulating exposure to mosquito-borne disease, the impact of the recent economic recession on mosquito control, how climate change may affect exposure to mosquito-borne disease, and how can communities aptly respond to an altered threat context. The literature in this review is drawn from the following EBSCO databases: Academic Search Premier, MasterFILE Premier; as well as J store and various internet sources when applicable. Keywords used either individually or in conjunction include mosquito control, disease, control measures, regulatory measures, and government agencies.

Mosquito Species and Diseases

Based on an examination of relevant literature regarding mosquito populations, it was noted by this study that the Culex mosquitoes, the Aedes mosquitoes as well as mosquito-borne encephalitis diseases, West Nile disease, St. Louis encephalitis, eastern and western equine encephalitis, and California encephalitides are the topics the cause the most concern for mosquito control agencies given their historic relevance in affecting the U.S. population (Wimberly, 147-156).

Encounters with Disease

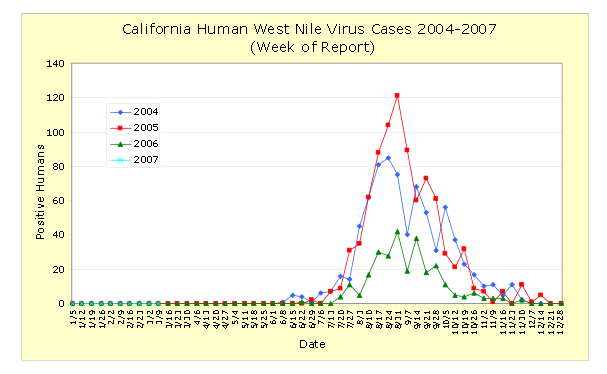

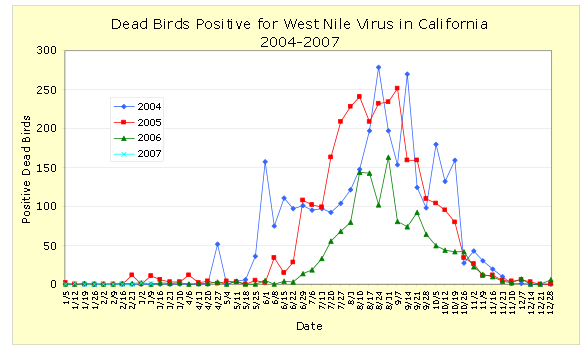

The West Nile virus arrived in the U.S. around 1998 – 1998 through either an infected bird (which is the most likely scenario given the distance involves) or an infected mosquito (which had taken blood from an infected bird) (Kitron, 611-620). The result was that by 2002 nearly 884 cases were reported in Illinois alone with 67 of those cases resulting in the death of the infected individual (Rasgon, 1-8). The following is a graphical illustration of the number of cases of the West Nile virus that were seen in California between 2004 and 2007:

As it can be seen, there is a distinct correlation between the increase in the number of human victims of the virus and the number of dead birds within the region that have died as a direct result of the virus. Based on this, it can be assumed that birds were the original carriers of the virus who had subsequently brought the virus from Egypt.

While the infection itself does not immediately result in death due to a certain degree of immunity infected humans tend to develop, the fact remains that the elderly and individuals with compromised immune systems (i.e. people in hospitals, those with HIV, or people that had previously taken strong antibiotics) are the most likely to die as a result of an infection (Charles, 128-139).

Another example of America’s encounter with mosquito-borne diseases can be seen in the case of St. Louis encephalitis which normally occurs in and around the Mississippi Valley and along the Mississippi river (Geier, 1490-1507). During the 1970s nearly 2,000 cases were reported in Missouri alone as a direct result of mosquitoes acting as vectors for the disease which originated from infected birds (Adams and Kapan, 1-10). One unique case of mosquitoes acting as vectors for disease comes in the form of the LaCrosse virus which primarily affects children. This particular vector disease is primarily seen in and around the state of California and is normally not fatal; however, it does cause complications in a child’s nervous system which can last for several years (Anderson et al., 26-33).

Current Practices in Dealing with Mosquito Populations

When it comes to handling mosquito populations, the following are the three main practices utilized by government agencies:

Focus on reducing/targeting mosquito breeding habitats

This action by various departments and agencies focuses on the mitigation of the mosquito threat by utilizing larvicide, adulticide, or source reducing mosquito habitats. In this particular action agencies utilized targeted or broad-spectrum pesticides that are either applied through a spray container or (and this is the method often utilized) through aerial distribution over a large scale area (Beier, 96-212). The result usually kills the larva and various adult mosquitoes which help to control the population of mosquitoes within certain areas.

The following chart is a comparison between the effectiveness of popular methods of reducing targeted breeding habits and their long term impact on mosquito populations.

As it can be seen, the use of pesticides (i.e. aerial pesticides) is the most popular and prevalent method of dealing with mosquito populations within the U.S., however, the next graph will show the effective impact it has had on mosquito populations in the long term.

As can be seen, areas, where pesticides were actively utilized, showed an increase rather than a decrease in the mosquito population while areas where other means of contending with mosquito populations proved more effective. The reasoning behind this is related to the development of certain levels of resistance to particular pesticides over time resulting in mosquito larva being minimally affected by the continued use of pesticides over a given area. The inherent problem though is that other species that would normally consume the larva are affected by the pesticides and cannot adapt as quickly resulting in fewer natural predators which would inevitably boost the local mosquito population in the long term. This technique also has the potential to create significant ecological damage to local flora and fauna depending on the strength of the pesticide in question and how much of it is utilized within a given period (Evidence Of Carbamate Resistance In Urban Populations Of Anopheles Gambiae S.S. Mosquitoes Resistant To DDT And Deltamethrin Insecticides In Lagos, South-Western Nigeria, 116-123). This is one of the reasons why alternatives to pesticide use are being pursued by local agencies at the present since they have been proven to be more effective and less environmentally damaging as compared to pesticide use.

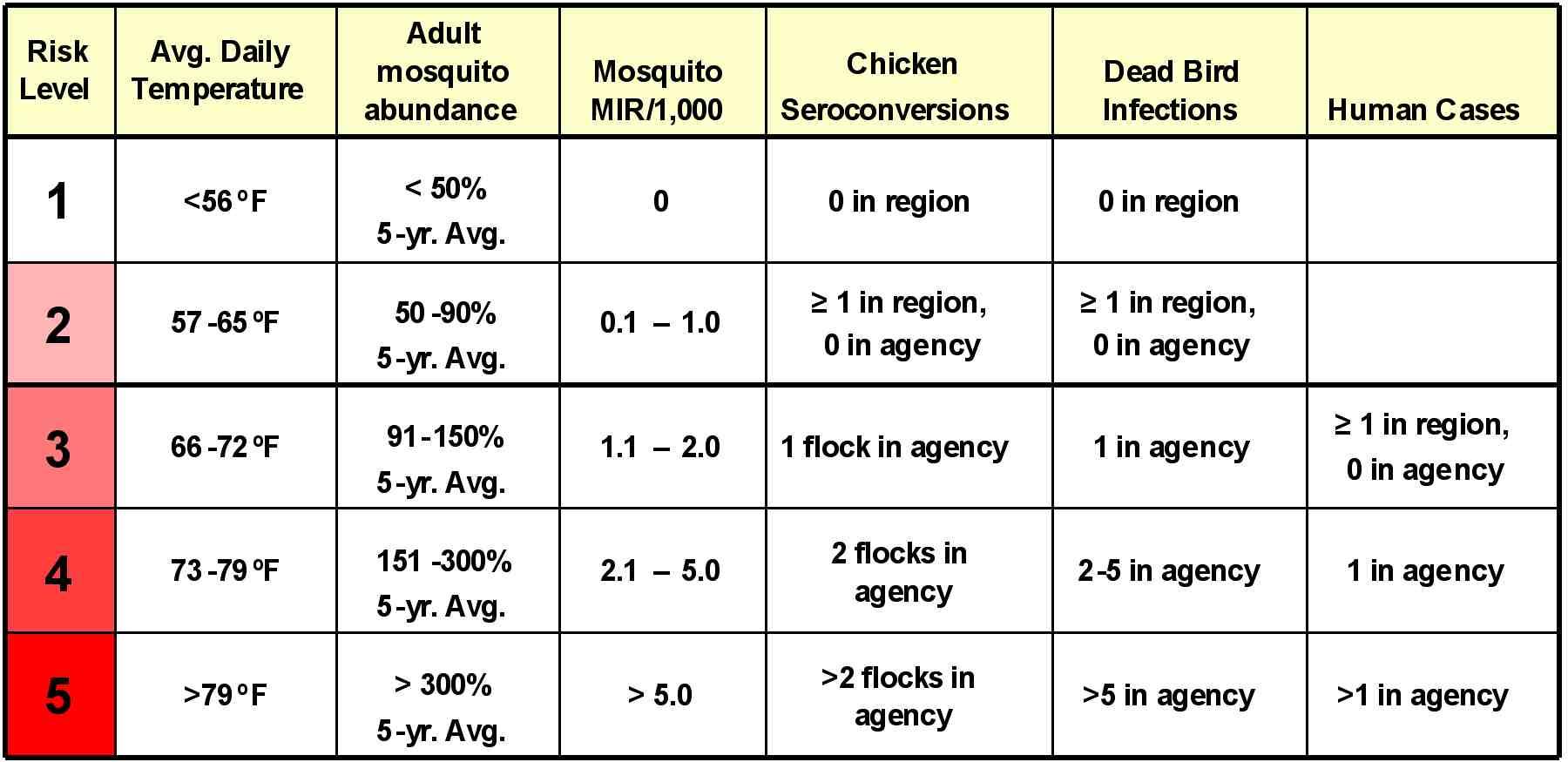

The following table is used by various government agencies within the U.S. to measure the “risk factor” of mosquito populations within particular regions/areas:

Through this table, government agencies can determine the level of responsiveness necessary to ensure that an outbreak does not get out of hand.

The last process for mosquito prevention is called source reduction which often entails a draining of “hotspots” that have become prime breeding grounds for mosquito populations (Ritchie, 303-316). This can entail locations as small as a birdbath or a swimming pool to areas as large as a local wetland.

Public Education

Public education comes in the form of the various roadshows, school presentations, public awareness campaigns, pamphlets, fliers, and other paraphernalia that are meant to draw attention to the inherent dangers surrounding mosquitoes and the necessity of taking the necessary precautions to ensure that an individual is not bitten. The main purpose of this practice is to educate the general public and create awareness, Gleiser and Zalazar (2010) describe this process as a proactive measure that is meant as a second line of defense due to the inherent limitations of agencies to respond to all possible threats involving mosquitoes before an outbreak occurs (Gleiser and Zalazar, 153-158).

Greenway, Patrick, and Chapman (2003) explain this situation by stating that aside from environmental factors, one of the main reasons why this particular method is focused on by numerous agencies is that it helps to reduce the number of cases of infections due to shared knowledge (Greenway, Patrick, and Chapman, 249-256). As a result, there is a progressive development within the local population which creates a considerable degree of concern regarding mosquitoes which makes them avoid them that much more and report instances where large populations of the insect have been noted within certain localities (Dumont and Dufourd, 162-167).

Monitoring and surveillance of mosquito populations

This practice often entails taking detailed population samples of mosquito population growth within certain areas of a rural or urban environment. This normally entails having to test local water sources for the number of mosquito larvae present and determining the size of the mosquito problem based on the number of larvae per sample that was collected (Raveton, 65-70).

Urban Development Practices that Contribute to Mosquito Ecology

Based on the study of Trawinski and Mackay (2009) which examined urban environments and their contribution towards the development of mosquito populations, it was noted that present-day waste management systems in the form of sewers, water reservoirs, and other artificial methods of trapping and collecting water within urban environments significantly contribute towards the population booms of mosquitoes within various cities (Trawinski and Mackay, 67-87). While Killeen (2006), does state that the fast-moving currents of various pipes and sewers do prevent the problem from getting out of hand, the fact remains that a certain level of stagnation does occur in some of these sewers resulting in the creation of an ideal area for breeding (Killeen, 154-158). These pools of water have several favorable factors for mosquito breeding such as:

- stagnation

- lack of predators within the water

- they are normally in dark areas that have a considerable level of precipitation

Based on these factors alone, it can be seen that it is the very method by which waste is removed from cities that contributes to the increase in mosquito populations.

Another area of concern comes in the form of the various rooftops of buildings that often go neglected by the building owner. Such areas, especially during the rainy season, accumulate considerable levels of stagnant water which allows mosquitoes to breed almost unabated.

Methodology

Introduction to Methodology

This section aims to provide information on how the study will be conducted and the rationale behind employing the discussed methodologies and techniques towards augmenting the study’s validity. In addition to describing the research design, this section will also elaborate on instrumentation and data collection techniques, validity, data analysis, and pertinent ethical issues that may emerge in the course of undertaking this study.

What is Qualitative Research?

Merriam (2009) in her book “Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation” explains that qualitative research is a type of exploratory research in that it tries to examine and explain particular aspects of a scenario through an in-depth method of examination (Merriam, 3-21). While it applies to numerous disciplines, it is normally applied to instances that attempt to explain human behavior and the varying factors that influence and govern such behaviors into forming what they are at the present (Merriam, 3-21). Thus, it can be stated that qualitative research focuses more on exploring various aspects of an issue, developing an understanding of phenomena within an appropriate context, and answering questions inherent to the issue being examined. It is based on this that the researcher chose a qualitative approach to be utilized within this study.

What will be examined?

In my research, I plan on comparing the cases of Houston, Texas, and Los Angeles, California. Both jurisdictions have detailed mosquito control plans as well as systems for regularly monitoring mosquito populations on a geographically discrete basis. Both cities also maintain records of citizen complaints, clinical data, and records of animals infected by the mosquito-borne disease. (Although Houston only tracks West Nile Virus). Both Houston and Los Angeles are major port cities and as such may act as loci for convergence of disease, host, and human from distant regions.

Following a review of mosquito abatement plans of both cities based on the available literature, I shall identify stakeholders involved in public health and mosquito control at local, state, and national levels that can comment on their activities with authority. I shall design a list of interview questions tailored to different groups of stakeholders with the intent of eliciting data that answer my research questions. There are to be approximately 15 stakeholders to be interviewed in total. The data collected will be analyzed to identify key themes and triangulated by examining secondary documents available in local media. This analysis will render findings and a subsequent discussion of those findings as they relate to my research questions.

Research Design

Sekaran (2006) observed most qualitative studies are either descriptive or experimental. The study will utilize a descriptive correlational approach because the participant will be measured once. Furthermore, it is imperative to note that the study will employ an interview technique to collect participant data from the aforementioned areas indicated in the previous paragraph. According to Sekaran, an interview technique is used when the researcher is principally interested in descriptive, explanatory, or exploratory appraisal, as is the case in this study. The justification for choosing an interview-based approach for this particular study is grounded on the fact that the participant will have the ability to respond to the researcher’s questions more directly and thus provide more information. An analysis of related literature will be used to compare the study findings with research on various strategies utilized by the CDC and other such agencies. Such analysis, according to Sekaran (2006), is important in identifying the actual constructs that determine efficient analysis because “it goes beyond mere description of variables in a situation to an understanding of the relationships among factors of interest” (Sekaran, 2006).

Participants

The research subjects that will be used for this paper will consist of various government agency officials that will be recruited at their respective agency offices within L.A. and Houston. All participants will be given a consent form encompassing what the study entails as well as assuring them that all responses will be kept strictly confidential and will observe proper research ethics in terms of ensuring that the data will not be leaked to the general public. Once the research subject has consented to be part of the study the interview will begin.

Data Analysis

The primary method of data analysis in the case of this study involves an individual review. The individual review will primarily be the researcher examining the collected response data from the officials that were interviewed and comparing it to the data obtained from the literature review. The researcher will then review these main themes and use this information to assist in establishing the key findings of the study. This method of data analysis is appropriate for a qualitative design.

Study Concerns

One potential concern that should be taken into consideration is the potential that the responses given by the study participants are inaccurate or outright false. While the researcher is giving the officials the benefit of the doubt, the fact remains that there is still the potential that the information being given has been crafted in such a way that it was made to ensure that it is false. Unfortunately, there is no way for the researcher to verify the information since only one research subject is being interviewed at a time per agency. This methodology exposes the participant to an assortment of risks that need to be taken into consideration during the research process. The main risk the participants will encounter is if any of the answers that criticize or indicate dissatisfaction with the processes of their respective agencies leak. This may have consequences on the attitude and opinion of agency officials towards them and can result in victimization. To eliminate this risk, the responses will be kept in an anonymous location. This way, the only way to access the information will be through a procedure that involves the researcher. The project thus observes research ethics in sampling as well as during the data collection process.

What qualitative method of the examination will be utilized and why?

It is at times necessary to conduct some method of examination wherein a researcher can more directly experience the attitudes and perspectives and teachers. The inherent problem though with utilizing a survey, as stated by Merriam (2009), is that the sheer potential randomness of the responses could result in a haphazard study that would need to find some way of categorizing random responses in a way that can be properly analyzed, a task which could take a considerable amount of time depending on the number of respondents utilized. It is based on this that interviews represent a possible alternative method of examination that can be pursued. As explained by Merriam (2009) interviews allow the researcher to draw on multiple sources of information to explain a particular subject or problem and, as such, allows for the creation of a far more succinct explanation of actions and events since it comes from multiple sources instead of single primary sources.

As such, from their perspective, interviews allow researchers to more directly analyze the subjects they are examining since an interview allows for a certain degree of “give and take” wherein while the interview is being conducted a certain degree of feedback is given by the research subject involving not only that topic being researched but other aspects that the researcher may have missed. It is the reciprocal nature of interviews as well as the fact that the research is more able to directly observe the reactions of the respondents and react accordingly that make interviews a decidedly superior method when it comes to instances where a researcher is trying to develop a more in-depth perspective about a particular population that is being examined.

Structured Interviews

One potential avenue of approach when it comes to utilizing an appropriate qualitative method in investigating the research topic is the use of a combination of open-ended survey questions and structured interviews. The advantage of utilizing open-ended survey questions and semi-structured interviews in a research study is that it allows the research subjects to give a variety of opinions, arguments, and generally accepted notions regarding a particular research subject without having the same restrictions found in structured and close-ended survey questions. As such, while this at times results in responses that are harder to categorize, it does enable a researcher to better understand issues from the perspective of those who constantly experience them and, as a result, enables the creation of far more accurate conclusions regarding the various problems that are occurring. It is based on this that a structured interview approach will be utilized during the data collection process.

Theoretical Framework

Introduction

This section elaborates on the use of attribution theory and grounded theory as the primary methods of examination utilized by the researcher to check the information gathered during the interviews. These theories were chosen due to their ability to examine the opinions of the interviewees to properly interpret the data and create viable solutions and recommendations. For example, through attribution theory, the research will be able to correlate the views of the CDC officials with their current experience in mosquito control to properly create a sustainable planning framework for the control of mosquitoes and the health threats they may pose. By following grounded theory during the data analysis stage of the study, the research will be able to determine the current effectiveness of current programs utilized by various government agencies in charge of mosquito control, whether significant problems exist, what the agencies are doing to address such issues and if possible alternatives to current methods have been considered. It is expected that by following the two theoretical frameworks during the examination process of the paper, the researcher will be able to succinctly address the research objectives of the study.

The main difference between the two theories is that attribution theory concerns itself with the assumptions people have towards a particular product or process while grounded theory focuses more on developing succinct assumptions based on the data that has been presented. As such, combining both methods enables a researcher to examine the opinions of the officials under an investigative framework while at the same time utilizing another framework to determine the inherent problems within a given scenario and the appropriate method of addressing them. It is based on this that these two theories become an ideal method for addressing the various objectives of the research topic. The main benefit of utilizing both theories in the examination of the research topic is that they enable a better examination of the responses of the interviewees as well as the data from the literature review as compared to merely examining both aspects utilizing a single theory.

Attribution Theory

Attribution theory centers around the derived assumption of an individual/group of people regarding a particular process, product, or service based on their experience with it. It is often used as a means of investigating consumer opinions regarding a particular product and to determine the level of satisfaction/sustainability derived from its use. By utilizing this particular theory as the framework for this study, the researcher will be able to correlate the opinions of the interviewees regarding their assumptions over what practices currently utilized by their respective agencies lead to proper mosquito control. This particular theoretical framework helps to address the research objective of determining current practices within the areas of L.A. and Texas by creating the framework that will be utilized within the interview and examination process. Utilizing attribution theory, the research will delve into the opinions of the government officials to better understand what factors influence their planning frameworks for controlling mosquito populations.

The needed information will be extracted through a carefully designed set of questions whose aim is to determine how a particular official’s experience with a process affects how mosquito populations are controlled in certain areas and whether, in their opinion, significant improvements need to be implemented or not. However, it should be noted that while attribution theory is an excellent means of examining the opinions of interviewees, it is an inadequate framework when it comes to determining the origin of problems in certain cases. Grounded theory, with its emphasis on utilizing a specific framework to guide a researcher during the examination process, can be considered an adequate method of performing the more “in-depth” aspects of the research.

Grounded Theory

The advantage of utilizing ground theory over other theoretical concepts is that it does not start with an immediate assumption regarding a particular case. Instead, it focuses on the development of an assumption while the research is ongoing through the use of the following framework for examination:

- What is going on?

- What is the main problem within the organization for those involved?

- What is currently being done to resolve this issue?

- Are there possible alternatives to the current solution?

This particular technique is especially useful in instances where researchers need to follow a specific framework for examining a problem (as seen in the framework above) and, as such, is useful in helping to conceptualize the data in such a way that logical conclusions can be developed from the research data.

By utilizing the framework of grounded theory to examine the responses from the officials and the data from the literature review, the researcher will be able to adequately examine the processes utilized within the CDC and other agencies related to controlling mosquito populations and whether such processes are effective based on the data collected. It is assumed by the researcher that there can be an effective correlation between the current problems of agencies in their control of mosquitoes and the diseases they carry with the planning frameworks that are implemented by individual agencies.

What you have to understand is that in qualitative research the concepts or themes are derived from the data. According to (), the grounded theory provides systematic, yet flexible guidelines to collect and analyze data. That data then forms the foundation of the theory while the analysis of the data provides the concepts resulting in an effective examination and presentation of the results of the study.

Research Results

Roles played by federal, state, and local agencies involved in monitoring and controlling mosquito-borne disease

Through the interviews, it was noted that federal, state, and local agencies work on what can be aptly described as a “multi-partisan” relationship wherein there is no clear regulatory framework (aside from assigned individual department responsibilities) when it comes to dealing with mosquito control. Instead, what exists is a type of informal network where departments on a federal, state, and local level communicate, cooperate and exchange resources and information to deal with mosquito control on either a “per case” basis or as a continuous relationship of collaboration and assistance (Killeen, 1-25). The basis behind this was elaborated on by one of the participants who stated that “no one wants their local districts, areas or states to have a disease outbreaks due to mosquitoes, as such, in the interest of implementing sufficient preventive measures it is necessary for inter-agency/department cooperation in the form of committees and inter-agency organizations to help relay the problem of mosquito control through a per area basis and relegate the necessary assistance in order to immediately deal with the issue at hand”.

As such, while there is no specific mandate that states that the department of fisheries for instance should help a local agency that deals with mosquito control, inter-agency committees and organizations help to set up the necessary means of communication and collaboration to help provide the necessary assistance. From this, it can be seen that the level of support on a vertical level that exists between agencies comes in the form of grants such as the “Enhancing Laboratory Capacity Grant Money” from the CDC, cooperation in terms of granting access to specific locations (ex: protected wetlands and underground waterways) for investigation as well as shared services for the creation of better public awareness regarding the threat of mosquitoes. On a local level, support can be seen horizontally in the form of inter-agency cooperation through shared manpower and communication wherein personnel from individual agencies collaborate to handle specific areas, perform a variety of scientific and investigative analysis as well as share information regarding “hotspots” and general public reports involving outbreaks to examine trends and determine what actions can be implemented through collaboration to prevent such a threat from getting worse.

Agencies and Budget Constraints

Agencies involved in mosquito control respond to budget constraints in three distinct ways:

- Through collaboration with state, federal, and local agencies to share manpower and resources to lessen the individual burden associated with cost reductions due to budget constraints.

- Cost-cutting in the form of process and equipment cutbacks (rarely in the form of employee layoffs).

- Applying for grants such as the “Enhancing Laboratory Capacity Grant Money” through the CDC or other forms of grants through public and private entities (i.e. other government agencies such as the Department of Health or local philanthropic organizations).

Based on the interviews from the local officials within L.A. it was noted that collaborative practices were one of the essential cornerstones in cost reduction because the main problem local agencies have to deal with comes in the form of a lack of sufficient labor coupled with the size of their respective jurisdictions. For example, in areas in and around L.A., some areas can comprise a total population of 6 million or more people. Local agencies dealing with mosquito control on a per district level can range from 50 to 100 personnel on average which have to investigate areas of several thousand kilometers comprising hundreds if not thousands of possible residences. This creates a distinct problem in terms of actually controlling mosquito populations with a constrained budget and a limited amount of personnel (Kitron, 1-4). As such, through inter-agency collaboration and communication, agencies that specifically deal with mosquitoes can ask help from local agencies of the department of health, department of public works, and even the department of waterways to help leverage the necessary manpower to investigate all areas and determine the extent of the action needed to deal with the mosquito menace (Kitron, 1-4).

How Public Health Agencies Plan for Change

An examination of the interviews reveals that several constraints hamper mosquito control and public health agencies from planning for change as mosquito-borne diseases emerge and climate change alters mosquito habitats in the future. These constraints are composed of the following:

Budgetary Constraints

One of the main problems when it came to planning for possible changes in mosquito populations, as a direct result of climate change, came in the form of the inherent budgetary constraints that many agencies face at the present. The issue lies in the fact that due to the limited amount of funds each agency is allotted every year, there simply is not enough in terms of purchasing the necessary equipment for future operations or hiring more personnel due to the level of uncertainty surrounding climate change at the present.

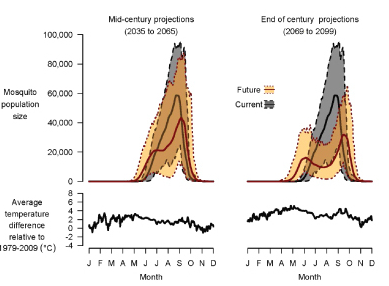

This graph shows the current project increase in mosquito populations based on temperature. As temperatures on the Earth increase, it creates a likelihood of greater mosquito population blooms.

It is uncertain whether the current progression of climate will either result in greater amounts of mosquitoes or result in population declines. As a result, agencies focus on addressing supply and personnel issues based on past trends in mosquito population blooms rather than speculative planning on events that may or may not occur at all. The present-day budgetary constraints faced by such departments, as a result of the financial recession, also hampers their ability to respond to future threats. It is due to this pest control agencies often require to collaborate with external partners such as other departments and agencies to supplement their already limited budgets.

Present Year Response Mechanisms

As mentioned earlier, future action on the part of mosquito control and public health agencies comes in the form of an examination of past trends in the increases/decreases of pests and adjusting operations and equipment needs based on the trend lines that were perceived. This is an endemic method of operation based on the literature and interviews that were read which shows how mosquito control agencies function more on a proactive basis of operation wherein they deal with problems as they appear rather than a more progressive method of operation wherein they focus on dealing with problems before they arise. While it may be true that agencies do in fact attempt to reduce mosquito populations by focusing on areas that have shown blooms in mosquito populations in the past before the problems appear, the fact remains that this method of operation still does not take into consideration the possible impact of climate change and how this could result in population blooms that agencies on a local level will be unable to handle despite considerable support from other agencies and departments.

Comparison between Texas and L.A. in terms of Mosquito Control Practices

When comparing both sets of interviews (i.e. officials who were from California and those from Texas) it was noted by the researcher that there was a considerable disparity in results in terms of developing the necessary inter-agency/inter-department cooperation that was noted in the case of California. For example, while Texas was noted as having several exemplary mosquito control programs in several of its cities, such is not the case when it comes to individual towns and districts which lack the same level of quality and comprehensiveness found in major metropolitan areas. This is in stark contrast to the case of California wherein a “broad spectrum approach” is utilized which ensures that there is little in the way of significant differences in the quality of program despite an area being rural or urban. The origin of such a problem maybe because there are insufficient committees, leadership initiatives, and cooperative agreements between agencies and departments in far-flung areas resulting in the development of different levels of quality in terms of provisioning the necessary amount of mosquito control in certain areas.

The following are two sets of data showing the amount of West Nile human infections within California and Texas as of December 12, 2012

This table shows the current population of each state under examination

What these tables reveal is that despite California having a larger population than Texas, it has fewer cases. Given the research of Williams and Rau (2011) which showed that larger areas with a greater distance between people would result in fewer cases, the fact that Texas has a larger area and lower population and still has more than triple the number of cases as compared to California is indicative of some other facilitator that is encouraging the number of cases to rise. One interpretation of the data is that the higher number of mosquito-related infections in Texas has been brought about by the insufficient practices utilized by the local mosquito control agencies. As it was mentioned earlier, the lack of sufficient inter-agency/inter-department cooperation and broad quality control mechanisms in Texas as compared to California has a high likelihood of affecting the ability of the state to properly manage its mosquito populations. The data are shown in the table above clearly shows the impact of such a disparity and the necessity of addressing it shortly.

On the other hand, the interviewees noted that one of the main reasons behind this disparity is connected to the sheer size of Texas itself when compared to California. The fact is that the individual districts in Texas are far too large and too distant for effective cooperative practices to be implemented and, as a result, individual regions have had to develop their processes based on local trends in mosquito populations. Since California is smaller with districts that are far closer to each other, this enables them to establish inter-agency/inter-department cooperative agreements wherein resources and personnel can be more effectively shared. It is based on this that the researcher has developed the conclusion that the size of the state in question influences the type of inter-agency/inter-department cooperative agreements that has a distinct impact on the type of mosquito control programs that can be implemented.

Proposed Framework for Cooperation between Government Agencies

The objectives of the framework for cooperation are as follows:

- Develop the necessary technology structure utilizing cost-effective software to enable mosquito control agencies to rapidly respond to public safety concerns presented by the local citizenry.

- Determine what management practices should be present that can be utilized to create a rapid response process to investigate problematic areas that have been identified.

- Create a crowd-sourced method of fire investigation wherein people can report the source of potential fires for investigation by the fire investigation team.

Based on the results of the interviews one of the main identified problems of mosquito prevention within most towns, cities, and urban areas is the proper identification of potential mosquito hazards before they become actual public safety threats. The interviewees explained that the current level of population density within most urban areas has reached such an extent that properly investigating every possible area where a mosquito breeding hazard is present is simply not feasible (Smith et al., 1957-1964). They point to the fact that most mosquito prevention services have a limited number of personnel present (ex: ranging from 20 to 100 depending on the location) and they are often tasked with determining the cause of mosquito population “blooms” and creating public service announcements or policies related to proper mosquito hazard prevention (Della Torre, 183-195).

They, in no way, could search an entire city or region and determine the location of every single hotspot before mosquito populations reach a distinct noticeable level even if the amount of personnel was increased by a factor of 10 (Severson, 1-9). Mosquito prevention departments often depend on the calls of local citizens regarding potential public safety hazards (i.e. dead birds, noticeable increases in the mosquito population, concerns regarding the standards by which a neighbor maintains their indoor pool, etc.) to properly identify them, however, such calls are few and far between which often leads to potential hazards becoming actual dangers for people and property alike (David, 407-416). It is due to this that the proposed management system for the L.A. and Texas service is the creation of a public crowdsourced method of mosquito hazard identification for agency investigators to follow potential leads and respond as necessary. The proposed public crowdsourced method of mosquito control investigation takes the form of a service similar to that of Ushahidi.com (which is African for “witness”).

This service utilizes current mobile phone architecture so that local citizens can identify “hotspots” on a map in combination with Google’s map service. The process such as these are more efficient than relying on human beings since they are not limited by human biology, rather they can be easily modified or adapted to perform ever more complex tasks (Agoramoorthy, 201-202). Such a feat is not possible with an average worker since they can neither be expected to move 10 times faster, grow 2 more heads, or have 10 arms. Not only that, mobile phones are a ubiquitous aspect of many residents of L.A. and Texas with many of them possessing smartphones that can connect to online applications (Lin, 671-680). By utilizing the Ushahidi application and placing a small message regarding the type of mosquito hazard present, an average citizen thus becomes an instrument that enables mosquito investigators to instantly know where potential mosquito hazards are present resulting in the creation of new policies or direct methods of intervention to address the problems found in the identified areas (Norris, 19-24).

The following is a table showcasing the potential impact of the crowdsourced method of evaluation as compared to present-day methods in investigation areas where mosquito cases are evident. Data for this data is based upon the average number of workers within various mosquito control departments within the U.S. as well as average population sets within specific towns and cities

Based on the data from the table above, it can be seen that crowdsourced methods of investigation enable a wider scope of data collection resulting in a greater likelihood to obtain larger amounts of data. This makes the investigation of mosquito blooms that much easier since average people with smartphones can act as investigators and inform the local mosquito control department regarding possible blooms in their area.

This would result in an efficient and effective method of addressing possible mosquito “blooms” thereby reducing their occurrence within Texas and L.A. It should also be noted that this particular type of software also enables investigators to see patterns and trends in the development of mosquito populations in certain regions. This results in better inter-agency and inter-department cooperation practices since it allows them to map the progression of mosquito populations thereby enabling to determine where responses need to be placed in real time (Raghavendra, Sharma and Dash, 22-25).

This type of mapping and information system can in effect take over from the previous incarnation of communication and information processing which can take a week or more before various agencies are informed regarding potential population explosions of mosquitoes within certain areas. Instituting a real-time citizen-based method of identification enables a better and more rapid response mechanism that would be able to “nip the problem in the bud” so to speak before mosquito populations reach levels that require considerable manpower and finances to control (Reed, 3-12). Another factor that should be taken into consideration is that an earlier and more rapid response time to reports regarding increases in mosquito populations in particular areas often enables agencies and various departments to imply a method of pest control that is not as environmentally damaging as compared to the widespread use of pesticides that could cause adverse environmental effects after the mosquito population has been dealt with (Naeem-Ullah and Akram, 452-453).

The activities for this project are as follows:

- Initial project inception wherein the incorporation of the investigators into local mosquito prevention agencies will be done.

- Hiring period of the investigators

- The training period for the prospective investigators

- Development and implementation of the crowdsourced mosquito investigation application.

- Promotion of the online application through local council initiatives as well as television and radio announcements that specifically target the populations of L.A. and Texas

- Development of the scheduling and management system for the online investigation team.

- Separating the investigation and search positions of the team on a revolving basis to ensure that all members of the team are familiar with the protocols and areas where reports of mosquitoes are concentrated

Conclusion

Based on what has been presented in this paper, it can be seen that what is necessary in the case of mosquito control for California and Texas is a crowdsourced method of communication and investigation wherein average citizens can use a smartphone application to help local pest control agencies identify hotspots and potentially problematic areas. Another factor that has been determined by this paper is that when it comes to mosquito control, a “one size fits all” strategy simply does not work given that different states and regions have a plethora of factors such as the size and distance of districts which impacts the capacity for inter-agency/inter-department cooperation to be achieved. It is based on this that this study recommends that when it comes to developing their strategies regarding pest control, individual agencies should be given a certain degree of lee-way since what applies in one state may not necessarily work in another.

Works Cited

AbuBakar, Sazaly. “Indoor-Breeding Of Aedes Albopictus In Northern Peninsular Malaysia And Its Potential Epidemiological Implications.” Plos ONE 5.7 (2010): 1-9. Academic Search Premier. Web.

Adams, Ben, and Durrell D. Kapan. “Man Bites Mosquito: Understanding The Contribution Of Human Movement To Vector-Borne Disease Dynamics.” Plos ONE 4.8 (2009): 1-10.Print.

Agoramoorthy, Ganesh. “Reviving Frogs In India’s Freshwater Environment To Control Mosquito-Borne Diseases.” Indian Journal Of Medical Research 129.2 (2009): 201-202. Academic Search Premier. Web.

Anderson, Alice L., Kevin O’Brien, and Megan Hartwell. “Comparisons Of Mosquito Populations Before And After Construction Of A Wetland For Water Quality Improvement In Pitt County, North Carolina, And Data-Reliant Vectorborne Disease Management.” Journal Of Environmental Health 69.8 (2007): 26-33. GreenFILE. Web.

Beier, John C. “Comparison Of Mosquito Control Programs In Seven Urban Sites In Africa, The Middle East, And The Americas.” Health Policy 83.2/3 (2007): 196-212. Print.

Beier, John C. “Dengue Vector (Aedes Aegypti) Larval Habitats In An Urban Environment Of Costa Rica Analysed With ASTER And Quickbird Imagery.” International Journal Of Remote Sensing 31.1 (2010): 3-11. Print.

Beier, John C. “Urban Mosquito Species (Diptera: Culicidae) Of Dengue Endemic Communities In The Greater Puntarenas Area, Costa Rica.” Revista De Biología Tropical 57.4 (2009): 1223-1234. Print.

Beier, John C. “Mosquito Species Abundance And Diversity In Malindi, Kenya And Their Potential Implication In Pathogen Transmission.” Parasitology Research 110.1 (2012): 61-71. Print.

Charles, Taylor. “Perspectives Of People In Mali Toward Genetically-Modified Mosquitoes For Malaria Control.” Malaria Journal 9.(2010): 128-139. Academic Search Premier. Web.

David , Jean-Philippe David. “Impact Of Environment On Mosquito Response To Pyrethroid Insecticides: Facts, Evidences And Prospects.” Insect Biochemistry & Molecular Biology 43.4 (2013): 407-416. Print.

Della Torre , Alessandra. “Development Of A Novel Sticky Trap For Container-Breeding Mosquitoes And Evaluation Of Its Sampling Properties To Monitor Urban Populations Of Aedes Albopictus.” Medical & Veterinary Entomology 21.2 (2007):183-195. Print.

Das, Paul. “The Mosquito Problem And Type And Costs Of Personal Protection Measures Used In Rural And Urban Communities In Pondicherry Region, South India.” Acta Tropica 88.1 (2003): 3. Academic Search Premier. Web.

Dumont, Y., and C. Dufourd. “Spatio-Temporal Modeling Of Mosquito Distribution.” AIP Conference Proceedings 1404.1 (2011): 162-167. Print.

“Evidence Of Carbamate Resistance In Urban Populations Of Anopheles Gambiae S.S. Mosquitoes Resistant To DDT And Deltamethrin Insecticides In Lagos, South-Western Nigeria.” Parasites & Vectors 5.1 (2012): 116-123. Print.

Ezanno , Pauline. “A Climate-Driven Abundance Model To Assess Mosquito Control Strategies.” Ecological Modelling 227.(2012): 7-17. Academic Search Premier. Web.

Ferguson, Heather M. “Linking Individual Phenotype To Densitydependent Population Growth: The Influence Of Body Size On The Population Dynamics Of Malaria Vectors.” Proceedings Of The Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 278.1721(2011): 3142-3151. Academic Search Premier. Web.

Geier, Martin. “Multi-Agent Modeling And Simulation Of An Aedes Aegypti Mosquito Population.” Environmental Modelling & Software 25.12 (2010): 1490-1507. Print.

Gleiser, R. M., and L. P. Zalazar. “Distribution Of Mosquitoes In Relation To Urban Landscape Characteristics.” Bulletin Of Entomological Research 100.2 (2010):153-158. Academic Search Premier. Web.

Greenway, Mark., Dale, Patrick Harold Chapman. “An Assessment Of Mosquito Breeding And Control In Four Surface Flow Wetlands In Tropical-Subtropical Australia.” Water Science & Technology 48.5 (2003): 249-256. Print.

Guiyun , Yan. “Population Genetic Structure Of Anopheles Gambiae Mosquitoes On Lake Victoria Islands, West Kenya.” Malaria Journal 3.(2004): 1-8. Print.

Killeen, Gerry F. “Community-Based Surveillance Of Malaria Vector Larval Habitats: A Baseline Study In Urban Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania.” BMC Public Health 6.(2006): 154-8. Academic Search Premier. Web.

Killeen, Gerry F. “A Tool Box For Operational Mosquito Larval Control: Preliminary Results And Early Lessons From The Urban Malaria Control Programme In Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania.” Malaria Journal 7.(2008): 1-25. Academic Search Premier. Web.

Kitron , Uriel. “Unforeseen Costs Of Cutting Mosquito Surveillance Budgets.” Plos Neglected Tropical Diseases 4.10 (2010): 1-4. Academic Search Premier. Web.

Kitron , Uriel. “Combined Sewage Overflow Accelerates Immature Development And Increases Body Size In The Urban Mosquito Culex Quinquefasciatus.” Journal Of Applied Entomology 135.8 (2011): 611-620. Print.

Lin , Shu-Chiung. “Exploring The Spatial And Temporal Relationships Between Mosquito Population Dynamics And Dengue Outbreaks Based On Climatic Factors.” Stochastic Environmental Research & Risk Assessment 26.5 (2012): 671-680. Academic Search Premier. Web.

Lydy , Michael J. “Aquatic Effects Of Aerial Spraying For Mosquito Control Over An Urban Area.” Environmental Science & Technology 40.18 (2006): 5817-5822. Academic Search Premier. Web.

Merriam, Sarah. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2009. 1-130. Print.

Naeem-Ullah, Uradu and Wisam Akram. “Dengue Knowledge, Attitudes And Practices In Multan, Pakistan: An Urban Area At The Verge Of Dengue Infestation.” Public Wealth (Elsevier) 123.6 (2009): 452-453. Academic Search Premier. Web.

Norris, Douglas E. “Mosquito-Borne Diseases As A Consequence Of Land Use Change.” Ecohealth 1.1 (2004): 19-24. GreenFILE. Web.

Paskewitz, Susan l. “Urban Wet Environment As Mosquito Habitat In The Upper Midwest.” Ecohealth 5.1 (2008): 49-57. GreenFILE. Web.

Raghavendra, Kataraina., Sharma, Parush and Atrushi Dash “Biological Control Of Mosquito Populations Through Frogs: Opportunities & Constrains.” Indian Journal Of Medical Research 128.1 (2008): 22-25. Academic Search Premier. Web.

Rasgon, Jason L. “Multi-Locus Assortment (MLA) For Transgene Dispersal And Elimination In Mosquito Populations.” Plos ONE 4.6 (2009): 1-8. Print.

Raveton , Muriel. “Experimental Bases For A Chemical Control Of Coquillettidia Mosquito Populations.” Pesticide Biochemistry & Physiology 101.2 (2011): 65-70. Print.

Reed , Kurt D. “Surveillance Of Above- And Below-Ground Mosquito Breeding Habitats In A Rural Midwestern Community: Baseline Data For Larvicidal Control Measures Against West Nile Virus Vectors.” Clinical Medicine & Research 3.1 (2005): 3-12. Print.

Ritchie, Sarah. “A Lethal Ovitrap-Based Mass Trapping Scheme For Dengue Control In Australia: II. Impact On Populations Of The Mosquito Aedes Aegypti.” Medical & Veterinary Entomology 23.4 (2009): 303-316. Print.

Skovmand , Ole. “Prevention Of Mosquito Nuisance Among Urban Populations In Burkina Faso.” Social Science & Medicine 59.11 (2004): 2361-2371. Academic Search Premier. Web.

Smith, David L., Jonathan Dushoff, and F. Ellis Mckenzie. “The Risk Of A Mosquito-Borne Infection In A Heterogeneous Environment.” Plos Biology 2.11 (2004): 1957-1964. Print.

Severson, David W. “Influence Of Urban Landscapes On Population Dynamics In A Short-Distance Migrant Mosquito: Evidence For The Dengue Vector Aedes Aegypti.” Plos Neglected Tropical Diseases 4.3 (2010): 1-9. Academic Search Premier. Web.

Trawinski, Paula and Derek Mackay. “Spatial Autocorrelation Of West Nile Virus Vector Mosquito Abundance In A Seasonally Wet Suburban Environment.” Journal Of Geographical Systems 11.1 (2009): 67-87. Print.

Urbanelli, Sarah. “Improving Insect Pest Management Through Population Genetic Data: A Case Study Of The Mosquito Ochlerotatus Caspius (Pallas).” Journal Of Applied Ecology 44.3 (2007): 682-691. GreenFILE. Web.

Vezzani, Darío. “Review: Artificial Container-Breeding Mosquitoes And Cemeteries: A Perfect Match.” Tropical Medicine & International Health 12.2 (2007): 299-313. Print.

Weill, Mylene. “Multiple Wolbachia Determinants Control The Evolution Of Cytoplasmic Incompatibilities In Culex Pipiens Mosquito Populations.” Molecular Ecology 20.2 (2011): 286-298. Academic Search Premier. Web.

Williams, Craig R., and Gina Rau. “Growth And Development Performance Of The Ubiquitous Urban Mosquito Aedes Notoscriptus (Diptera: Culicidae) In Australia Varies With Water Type And Temperature.” Australian Journal Of Entomology 50.2 (2011): 195-199. Academic Search Premier. Web.

Wimberly, Michael C. “Satellite Microwave Remote Sensing For Environmental Modeling Of Mosquito Population Dynamics.” Remote Sensing Of Environment 125.(2012): 147-156.