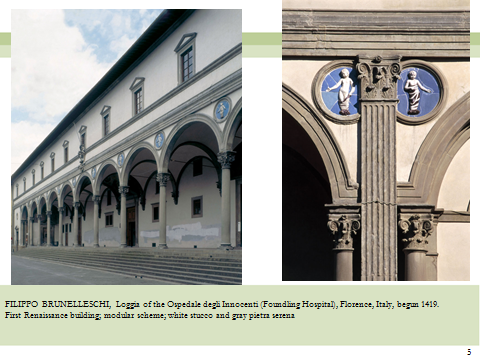

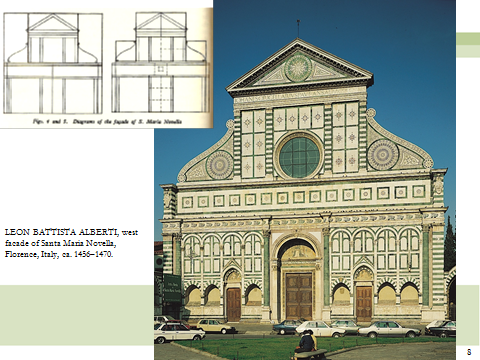

Among the western countries reminiscent of the two forms of architectural styles is Italy. A discourse by Fazio, Moffett and Wodehouse shows the successive development and evolution of architecture in Italy which illustrates the inclusion of the divergent forms of dynamism, conscious development, and material culture into the two forms of architecture. Besides, the inclusion of the Roman thoughts and ancient Greece into different architectural styles define the renaissance and the baroque periods (3). Each form or style emerge uniquely reflects the sources of inspiration based on the liberal use of the Doric elements, Corinthian, and Ionic orders combined with humanism and the classical forms that crystalize in the transition path from the renaissance to the baroque periods. Watkin accurately describes the difference between the two forms of architecture as illustrated in the detailed discourse of the differentiating elements in the form of lines, perspectives, space, content, and clarity that are conceptualised in the five formal principles developed by Heinrich Wolfflin (7). This is embodied in the key defining elements of the renaissance and baroque architectures as clearly demonstrated by the Loggia of the Ospedale degli Innocenti by Filippo Brunelleschi and the facade of Il Gesù by Giacomo Della Porta in Rome, Italy as shown in figure 1 and 2 respectively.

The composition of the Ospedale degli Innocenti illustrated in figure 1 was designed by Filippo Brunelleschi. It clearly illustrates the different areas of the courtyard, the chapel, ground floor, and a large hall. The shapes and appearances were due to the use of local materials in the construction of the squared pavements of the Pietra Bigia, Pietra Serena porticos, and the pools of the Pietraforte with stairs (Kostof 4). Besides, the ground plan demonstrates a disposition of a symmetrical structure with an inclusion of mentioned compartments expressed in an antique style. The space among the rooms depicted a geometrically logical proportion in design with rhythm and form as opposed to the mediaeval architectural forms. A clear distinction of the forms illustrates circular and semi-circular forms with repeatedly applied identical volumes on the structure. Here, the plan and section illustrated the regular occurrence of the diameter of the arch resulting into a three dimensional object. That is in addition to the inclusion of humanism as reflected in the spatial dimensions that occurred as a reflection of the psychological and functional needs of the people. A critical analysis of the Ospedale degli Innocenti shows that it differs from the facade of Il Gesù in the context of new explorations and forms, shadows, light, and dramatic style and intensity as clearly depicted in the wealth and power of the Italian courts that was blended in the philosophy and culture of the people.

A probing introspection of the facade of Il Gesù by Moffett, Fazio and Wodehouse reveal the first baroque façade in architecture with a significance deeply embedded in the Roman order of the Jesuits. That was constituted in a plan that reflected the religious beliefs of the Catholic Church in response to the growth of the protestant church (22). This was a period that was characterised by scientific development, geographic colonisation, new discoveries in astrology, religious, and political conflicts. In reflection of the external environment, the plan of the building took the form of the traditional cruciform basilica constituting the aisles and naves in the entire length of the architectural piece. The interior of the structure’s two stories were designed to communicate the architectural motifs of the Greek, Romans, and the Renaissance periods in form of arched pediments, scrolling volutes, engaged columns, double plasters, windows, and Corinthian Capitals. Ingersoll and Kostof single out the inspiration depicted by the baroque architecture in the ornamental façade of the church of II Gesu (11). Here, the architectural piece was presented as a massively heavy form with several fragments as evidenced in the two stories of the building. The corners were curved to give the feeling of constant movement as depicted by the use of ornamental elements at the points of entry.

Significance of the buildings/landscapes and their evolution

James-Chakraborty importantly shows a clear illustration of the successive evolution of each structure as differentiated in the style and design and reflection of the surrounding landscapes. The results reveal the true relationships between the renaissance and the baroque as the two architectural styles emerged. The Loggia of the Ospedale degli Innocenti renaissance architecture revealed an era in history where culture was a reflection of the external environment in both the historical and physical forms embodied in the formations of rocks that prevailed in the physical environment of the Pratomagno. However, the birth of the baroque architecture emerges in importance as an expression of a period dominated by a spiritual era besides. The fundamental difference between the renaissance and baroque architectures is in the nature of the details of the interior and exterior portions of the structure.

In conclusion, it is evident that the renaissance and baroque architectural periods occurred successfully but differed in style and form on the basis of the principles adopted in the design of the Loggia of the Ospedale degli Innocenti by Filippo Brunelleschi and the facade of Il Gesù by Giacomo Della Porta in Rome. The significance emerges in the wealth and religion of the people besides accurately demonstrating the use of the principles geometry to achieve accuracy and proportionality apart from being examples of the historical evidence of the belief systems, and humanism leading to structurally stable buildings.

Works Cited

Fazio, Michael W., Marian Moffett, and Lawrence Wodehouse. A world history of architecture. Laurence King, 2008.Print.

Fazio, Michael W., Marian Moffett, and Lawrence Wodehouse. Buildings across time: An introduction to world architecture. McGraw-Hill, 2007. Print.

Ingersoll, Richard, and Spiro Kostof. World architecture: a cross-cultural history. Oxford University Press, 2013.Print.

James-Chakraborty, Kathleen. Architecture Since 1400. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014.Print.

Kostof, Spiro. A History of Architecture: Settings and Rituals, New York: Oxford, 1995. Print.

Watkin, David. A History of Western Architecture, New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 2000. Print.