Introduction

Jewish artists have real pieces of art works as history reveals. Jewish artists have created pieces of arts for at least the last 2,000 years. These are evident from paintings of “18th century, 500 years of making ritual objects and illustrated prayer books, haggadahs, megillas, ketubos and the extensive production of illuminated manuscripts between 1300 and 1500” (Sed-Rajna 237). In addition, there are several pieces of arts in Israel mainly in synagogues. These reveal arts of fourth to sixth centuries (the Common Era). The origin of such works was Dura Europos.

The Dura Europos

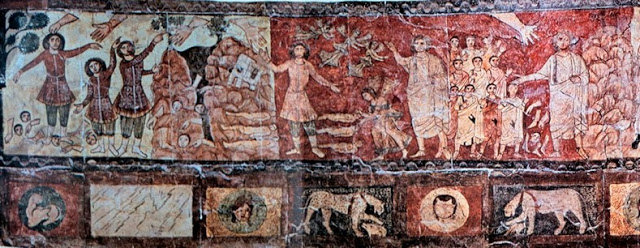

The Dura Europos paintings represent a great deal of the Jewish art. According to Sed-Rajna, a Jewish art scholar, Jewish art portrays an iconographical language with elements of narrative language. He notes that there are three types of narrative arts as follow:

- Symbolic Narrative

- This category has murals of Joshua, Messiah, Moses ascending Mount Sinai and at the Bush, Torah niche, and Abraham and the Covenant (Sed-Rajna 229).

- Sequential Narrative

- This area has murals of the Exodus, Elijah, Ezekiel, Triumph of Mordechai, and the Valley of the Dry Bones (Sed-Rajna 230).

- Comparative Narratives

- There are paintings of the Well in the Wilderness, the Ark in the Temple of Dagon, and Tabernacle (Sed-Rajna 230).

There are many categories and identifications of Dura Europos and frescos paintings. However, most of these classifications are under scholarly debates. It is only these three areas, which scholars have reached a consensus. Based on such differences, various art scholars have expressed different views on Jewish arts.

For instance, some scholars have focused on didactical and historical elements of the art. Others have considered frescos as commentary part of the official Roman art. In addition, thematic concerns usually involve Messianic elements according to Erwin. There are other different opinions on Jewish art (McBee 1). Such views only express how Jewish art can draw various meanings due to its richness.

Symbolic Narrative

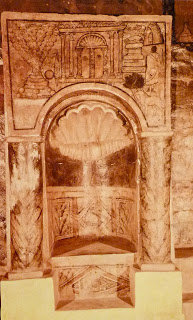

Torah niche is a striking part of the synagogue with various paintings, which bear different interpretations. It has murals of Jacob blessing his sons. However, much repainting has damaged the piece. This painting may depict Moses, Abraham, and Joshua at different occasions.

The Torah niche has a definite figurative representation. It represents “a closed temple, temple menorah, and a lulav and esrog on the left” (McBee 1). This was the ideal form of representation for over 300 years in synagogues. On the right, there is the Binding of Isaac. We can also observe a tied ram and Abraham with a knife. “Isaac is on the altar while a hand from heaven” (McBee 1) prevents the pending sacrifice to God.

Others argue that there is an insertion of Sarah standing outside the tent on the upper right of the painting. It shows Sarah’s reaction and comprehension of the ongoing events. According to Sed-Rajna, “the scene is the first attempt in Jewish art to transpose a literary account into visual form” (Sed-Rajna 239). As a result, it signifies the change in representation from symbolic art to narrative. This mural is important because it is among many Jewish paintings attributed to sacrifice.

We cannot underestimate the relevance of these murals in Jewish art. This painting was among the earliest works of art in Jewish paintings.

It became a model for many synagogues for over a period of 300 years. Akeida was the pictorial narrative that focused on representing the Jewish religion in the form of painting. The painting achieved this by utilizing the local culture to reinforce the Jewish religion and the role of God and mercy in their lives. It is also interesting to note that some of the images do not represent Sarah as others do.

This painting marked the start of Jewish art. This mural is complex and many scholars agree that it has a rich history, but a thorough study of Dura Europos reveals unknown mysteries.

Sequential Narrative

Most of Dura Europos paintings relied on Torah narrative in order to capture complex issues and affairs of communities. Dura Europos paintings bear the greatest representation in the Jewish art history.

It also has various aspects of Torah subjects, which are the most outstanding form of paintings in Jewish art. However, some paintings with illuminated Haggadahs from Spain took this legacy after thousands of years. We also note that the idea of “decorated synagogue only reappeared later in the 17th century due to shuls paintings of Russia, Poland, and Lithuania” (McBee 1).

Dura Europos murals in synagogues also have extensive figuration. There are images, which show followers on the walls. However, according to McBee, close examinations of these images reveal that they represent “Torah figures, Abraham, Moses, Samuel, and Elijah” (McBee 1) in Roman attires. These show that such figures were statesmen and heroes of the time. However, they lead to confusion on the difference between Gentile and Jew.

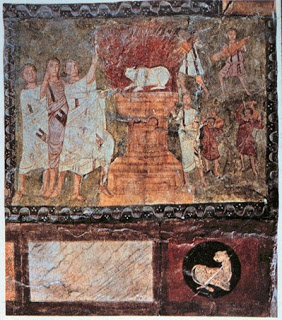

These murals have also presented problems in relation to factual consistencies. For instance, murals of Exodus do not concur with the narrative sequence. The Temple of Aaron during sanctification highlights “a bull about to be killed with an ax” (McBee 1). This does represent the normal Jewish tradition of slaughtering bulls.

Still, on the Solomon’s Temple, the doors have decorations with pagan elements. Lastly, the painting on Rescuing Moses shows that Pharaoh’s daughter had no cloths. These variations in interpretations of Jewish art in synagogues represent various ideas, which scholars have attached to these paintings.

Such differences in representation of paintings may have taken place due to borrowing of non-Jewish styles for Jewish paintings. For instance, we have the application of Zodiac that highlights God’s power over the world by his worldly agents. This representation also has a chariot and sun. Artists combined both elements to reflect paintings of the time in the synagogue.

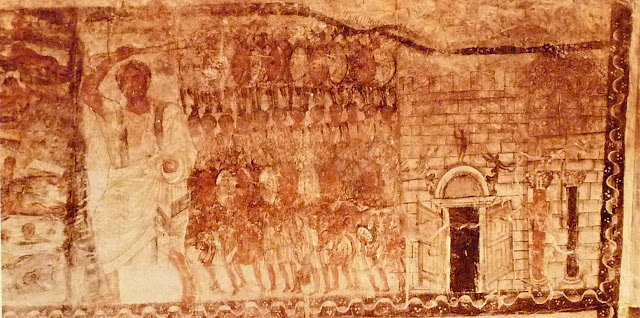

The most represented form of painting in the Dura synagogue painting is Moses at the time of the Exodus. It occupies the upper right wall with depiction that across run from left to right. Moses is conspicuous with his soldier has he leads them out of Egypt. A closer look reveals that there is an open entrance of Egypt, which has deities. These deities show paganism in Egypt, which Israelites must leave.

We also have a flat aerial view that depicts the sea. It is full of drowned Egyptian soldiers. Again, Moses leads Israelites with his rod in his stretched hand over the sea. Moses also leads Israelites across the sea as they match along 12 lanes. We also notice the ‘Hand of God’ on these paintings has it directs Moses through the Exodus event.

The artist must have been familiar with the events of the time and Jewish tradition. The Exodus painting shows Moses as he leads Israelites out of Egypt with God’s guidance. It depicts the Jewish triumph over Pharaoh’s paganism and the oppression.

The paintings of Dura Europos synagogue also have significance in the third century. Most scholars look at the importance of such murals in relation to their place in history.

They serve the purpose of encouraging modern Jewish artist and showing them possibilities from the past. Dura Europos is the only Jewish narrative art that has “Torah, midrash and individual creativity, which span a gap of 1700 years and, with imagination, finding parallels and inspiration between their worlds” (McBee 1).

A thorough review of Dura Europos paintings and frescos shows fundamental elements of early Jewish art. Torah niche employed both the use of symbols and narrative techniques in order to create meanings evident in the Temples.

Exodus paintings reveal the triumph of Israelites against Pharaoh’s paganism and slavery. Rescuing of Moses shows Pharaoh’s daughter rescue the infant. These pieces of art works use both midrashic and Biblical elements in order capture history of the time. They also use non-Jewish elements to enhance visual features of paintings.

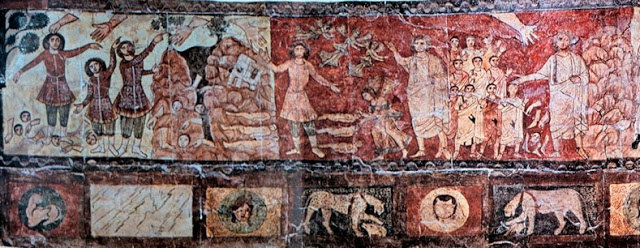

Some of the most important paintings in Duran Europos painting are those of Elijah and Ezekiel. These paintings also attack paganism at the time. Scholars draw this conclusion by performing comparative narratives.

Scholars have used continuous narrative in order to explain paintings depicting Elijah. Such paintings depict divine intervention for the community and for himself. There is also the unsuccessful struggle that involves Elijah and Prophet of Baal on Mount Carmel. We can see eight priests in their Roman attires next to the altar with the god’s sacrifice. Below the altar, there is also a small animal ambush by a snake.

It represents the evil, Hiel of Ahab. He wanted to light the fire. However, the serpent from God consumed him before he could light the fire. We can also see Elijah’s sacrifice on fire. He is evoking the heavenly fire and calling for drenching of the sacrifice because of the interference by evil forces. These paintings depict a war against paganism in which God comes to the rescue of true believers.

In the paintings of Ezekiel, the presence of God is eminent through the visible hands on the top of the paintings. This reflects the important prophetic role of Ezekiel among the Jews. He stands for the redemption of the entire community. The first image reveals how “Ezekiel ended up in the valley of the dry bones” (McBee 1).

In the valley, we have features that represent feet, hands, and heads. Ezekiel must provide his prophecy about the importance of these features. The meaning represents coming back to life because this is the interpretation from God. Further, we also see the three angels and another one on the ground as they perform miracles.

We also notice Ezekiel adorned in Roman attire in another part of the painting. This represents the return of ten tribes that disappeared. These are the ten men with Ezekiel. It also shows resurrection of Israelites during the period of Ezekiel. The presence of the ‘Hand of God’ is also conspicuous in this painting. Scholars claim that these paintings highlight the role of God in resurrection of Israelites as a nation and individuals after their deaths.

According to Elsner, “one fundamental theme to the Dura murals is something called Cultural Resistance (Elsner 269). Elsner argue that Jewish paintings rebuked cult religion that was in Dura. Therefore, these paintings aimed to eliminate paganism and restore the Jewish monotheism among people who were losing their cultural identity.

Such paintings in the synagogue dispel the claims that Jewish did not allow visual images in the synagogue. Scholars consider this prohibition has the most misunderstood part commandment in relation to arts. They point out that it refers to the creation of idols and not artistic representations in arts.

However, the interpretation this command often varied with time. This because others followed it strictly while others gave a loose interpretation. In this context, we can argue that earliest works of Jewish celebrated art works and used visual arts as ways of honoring God. This was the purpose of paintings in the Dura Europos synagogue. Therefore, we can see how religion influenced lives of Jewish through arts.

Comparative Narrative

From the comparative, we look at the Aaron’s Temple and the Miraculous Well. The paintings depict variations in Jewish arts. We have the Ark and the Dagon Temple in which we interpret a message of victory. Other paintings depict rigid systems with no human beings present. Such paintings represent broad ideas and schematic representation.

Scholars consider such images as non-Jewish because of the pagan elements on the closed door. Therefore, it is a wasteland in which no religion or life can thrive. The comparative narrative aimed to depict that paganism did not stand a chance in the Jewish land because of the destruction of the idols.

Conclusion

The Dura Europos has demonstrated the three interpretations of the paintings in the synagogue. These are various narratives like symbolic, continuous, and comparative. These paintings are complex, and we can only understand them through classification. This is because the paintings involve a number of elements from both the Bible and the midrash. In addition, we also have to deal with the artist’s point of view.

The artists have depicted ‘Hands of God’ to mark his presence in most of the events of the Jewish. Such Jewish arts show possibilities that paintings can capture with imaginative approaches. We have to understand various figures, attires, and motifs of the paintings, which give us rich imageries and depictions of Jewish art.

The Dura Europos represents the earliest work of arts by Jewish. Scholars and artists have to start from this foundation in order to understand contemporary works of Jewish arts. Therefore, Dura Europos paintings shaped the way for future arts of Jewish.

Works Cited

Elsner, Jas. “Cultural Resistance and the Visual Image: The Case of Dura Europos.” Classical Philology, 96.3 (2001): 269-304. Print.

McBee, Richard. Dura Europos Project II at UJA New York . 2010. Web.

Sed-Rajna, Gabrielle. Ancient Jewish Art: East and West. Secaucus, NJ : Chartwell Books, 1985. Print.