Canada’s Government and Social Structure

The Canadian government, as well as their social structure, has gone through a couple of changes over the years between the 19th and the 21st centuries. It was previous identified as the Dominion of Canada, and even though this name still remains legal, it is rarely used in the conventional and legal setting (Dunn, 2010). The government was previously a total monarch under the queen of England, but over the years, there was the adoption of the West minster style federal parliament (Bernier & Potter, 2001). This makes the government of Canada be a democracy within a constitutional monarchy.

The country is divided into different centers of governance, with ten provinces and three territories being carved out of the total geography of the country (Kernaghan, 1999). These include British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Quebec, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Saskatchewan, Northwest Territories, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, Nunavut, Ontario, and Yukon (Bernier & Potter, 2001).

The Westminster system of governance is based on unwritten conventions as well as written legislation (Inwood, 2011). There is the adoption of the English common law in the legislation of all matters that fall within the federal jurisdiction as well as in all provinces except Quebec (Carroll, Sproule-Jones & Siegel, 2005). Quebec’s administration is based on the civil law, which is borrowed from the Custom of Paris as it were in the pre-revolutionary France, and it is set out in the Civil Code of Quebec. The country accepts the compulsory International Court of Justice jurisdiction though there are a number of reservations (Hessing, Howlett & Summerville, 2005).

Under the monarchy, the head of state is currently identified as Queen Elizabeth II and the Viceroy and Governor-General of Canada, who is David Lloyd Johnston (Dunn, 2010). The country’s executive power lies in the office of the Prime Minister, who is the head of government (Inwood, 2011). Ministers are also included in the executive, and they are responsible for the management of government affairs (Bernier & Potter, 2001). The Legislative power of the country lies in the bicameral Parliament of Canada, which consists of three arms identified as the Senate, monarch, and finally, the House of Commons (Kernaghan, 1999).

SWOT analysis

The Canadian administrative system has been identified to have particular strengths that have served to improve and empower the lives of Canadian citizens. One of them is their adoption and preservation of democracy. This has served to improve the overall living conditions of the Canadian citizens as well as increased their observance of the basic human rights in the country, despite its combination with the monarchy system of governance (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005).

The monarch, on the other hand, gives them a particular strength as a supreme government that cannot be broken down by negative political forces. This has also ensured that they have a high mandate in the commonwealth and gives them the direct advantages that other commonwealth members enjoy (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005). The division of the country into 13 administrative centers also works to ease the process of governance as well as to ease the distribution of government resources (Kernaghan, 1999).

This ensures that all the states are in a position to identify their particular and unique needs then move to solve them in the best way that their leaders identify will work best with the support of the national government (Carroll, Sproule-Jones & Siegel, 2005).

The legal system borrows from the English as well as the French legal systems that are in place now and in history, and this means that they have laws that are rich in human principles that have been tried and tested over time (Graham, 2007). This is coupled with their parliamentary system that serves to ensure that those laws are suited for the particular needs of Canadian citizens (Hessing, Howlett & Summerville, 2005).

There are also some weaknesses in the governance as well as the social structures of Canada, with their dependence on England being identified as one of the major weaknesses (Graham, 2007). The making of decisions has also been identified to be quite slow in the government, especially due to the different considerations that have to be made for the different federal administrations (Dwivedi & Mau, 2009). The Canadian administration faces the threat of being redundant, especially in dealing with modern and unique administrative challenges as it is identified that there is very little that a rigid government that still conforms to monarchical powers can do (Dunn, 2010).

It is, however, identified that the Canadian administration offers the Canadian citizens the opportunity to grow their social standing as well as their political structures (Hessing, Howlett & Summerville, 2005). There is still room for improvement in the current administration, especially with the rapidly changing administrative challenges that the current world has to offer (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005).

SWOT analysis of the Canadian administration

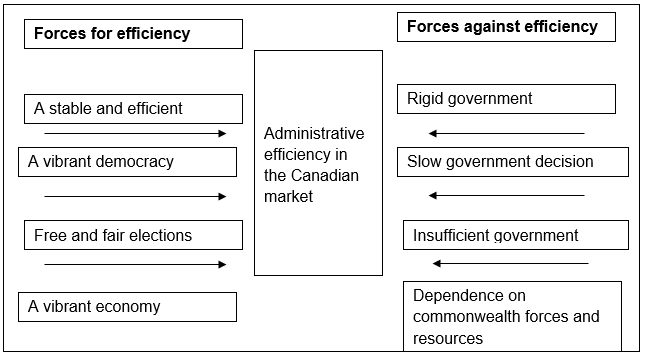

Force-field analysis

The public administration in Canada is specifically efficient in the identification as well as the voicing of the citizen’s welfare issues, and this has served to improve the general state of life in Canada (Dwivedi & Mau, 2009). It is identified that the legislature is specifically responsible for identifying the particular needs of the population in all aspects of governance and providing solutions in terms of their governance, economic as well as social well being (Carroll, Sproule-Jones & Siegel, 2005).

The democratic nature of the government, as well as the fact that their executive and legislative leaders are elected through free and fair elections, means that the country has a lot to look forward to in terms of improved administrative services even with the emergence of new and unique challenges every day (Graham, 2007).

The fact that the country is divided into thirteen administrative centers has served to ease the administrative process as well as the distribution of resources (Inwood, 2011). Over the years, the Canadian administration has been able to put in place superior education, health as well as economic sectors, and this has fueled their economic performance to a point where the Canadian citizens are identified as among the most comfortable and happy people in the world (Schiavo-Campo & Hazel 2008).

It has been identified that their consultation as well as adherence to the English administrative as well as legal systems and in the case of Québec, the French systems, makes it harder for the administrators to come up with unique solutions to the unique challenges that are posed by the Canadian population (Dwivedi & Mau, 2009).

With the different needs of the different federal governments, the government has always found itself stretched in terms of revenues as their financial obligations are quite high. The fact that the management of all these federal and national governments, as well as the monarch, requires a substantial amount of money serves to worsen the situation even further (Schiavo-Campo & Hazel 2008).

Challenges facing the administrative system

The Canadian administrative system has been facing autonomy challenges over some time now as their previous fascination with their attachment with England is fading off (Dwivedi & Mau, 2009). It is identified that most of the executive decisions in the country have to borrow some level of approval or rather has to be a result of the consultative effort between the Canadian leadership and the English monarchy (Schiavo-Campo & Hazel 2008).

This has led to certain challenges, especially in issues that are unique to Canada and cannot be applied in England. It is identified that repercussions to administrative challenges in England have been transferred to Canada even though they are thousands of miles apart (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005). This has had an adverse effect not only on its governance system but also on its economic performance

The Canadian administrative system currently suffers from insufficient resources. It is identified that since the parliamentary system has ensured that the citizens’ needs are quickly identified, there has been the identification of too many needs that the government has had to selectively prioritize them to ensure that there is an equitable distribution of resources (Graham, 2007).

The current government structures have, however, been identified to be particularly effective in solving some of these challenges even though there is still a lot that has to be done (Schiavo-Campo & Hazel 2008). The fact that the country has a vibrant economy that is still growing means that they may be in a position to solve most of their economic as well as social challenges, but there is the need to have more political will from the particular administrators for the country to fully achieve efficiency in its administrative as well as social systems (Hessing, Howlett & Summerville, 2005).

References

Bernier, L, & Potter, E. (2001). Business Planning in Canadian Public Administration. Ottawa: Institute of Public Administration of Canada.

Carroll, B, Sproule-Jones, M, & Siegel, D. (2005). Classic Readings in Canadian Public Administration. New York: Oxford University Press.

Dunn, C. (2010). The Handbook of Canadian Public Administration. New York: Oxford University Press.

Dwivedi, o., P, & Mau, T., A. (2009). The evolving physiology of government: Canadian public administration in transition. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press.

Graham, L., S. ed. (2007). The Politics of Governing: A Comparative Introduction. Washington DC: CQ Press.

Hessing, M, Howlett, M & Summerville, T. (2005). Canadian natural resource and environmental policy: political economy and public policy. New York: UBC Press.

Hofstede, G, & Hofstede, G., J. (2005). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Inwood, G., J. (2011). Understanding Canadian Public Administration: An Introduction to Theory and Practice. Toronto: Pearson Education Canada.

Kernaghan, K, & (1999). Public administration in Canada: a text. New York: ITP Nelson.

Schiavo-Campo, S, & Hazel M., M. (2008). Public Management in Global Perspective. Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe.