Introduction

The continued integration of a state’s financial markets means that most modern debt and financial crises have cross-border impacts. The effects often limit the policy options available to governments, which necessitates international cooperation (Lim et al. 327). The Greek government suffered a financial crisis that demanded three separate bailouts in 2010, 2012, and 2015 (Lim et al. 327). In each of the negotiations, the Greek government was subjected to externally imposed refinancing deadlines and regulations, which in some instances, were in direct contravention of Greek policies. The Eurozone’s flawed systems and false promises are the basis upon which the Greek government should base its arguments for an immediate exit from the union.

Reason for Joining the European Union

The main reason the Greek authorities presented as their motivation to join the European Union was the economic stability that would result from the adoption of a single regional currency. Since joining the European Union fifteen years ago, Greece has suffered an economic depression that is comparable to the 1930s economic crisis experienced in the United States (Raudon and Shore 69). The Greek GDP fell by 25% between 2009 and 2015, and unemployment rates are among the highest in the region, as demonstrated by an increase from 7.7% in 2008 to 23.5% in 2016 (Raudon and Shore 69). Greece’s economic situation is a demonstration of the fact that its membership within the European Union is a liability.

Flawed EU system

The European Union’s deal to save Greece from its economic challenges is an intrusion on the nation’s sovereignty. The European Union is actively micromanaging reforms to the country’s product and labor markets. External institutions have been tasked with the supervision of the country’s domestic economy and facilitating a complete overhaul of its public administration system. The asset fund promised by the European Union will be supervised by hand-picked officials, which will force Greece to reverse measures it enacted to address its economic challenges.

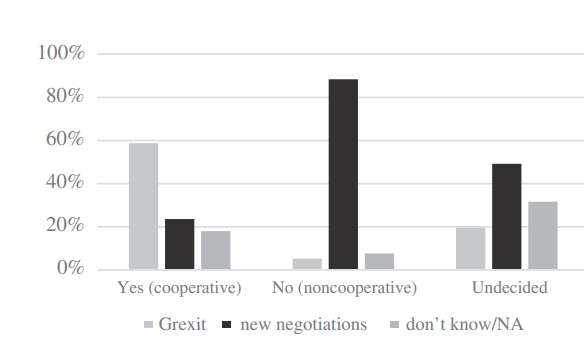

The flaws of the European Union’s system were evident during the Greek referendum campaign. For instance, the European Commission President, International Monetary Fund Director, and German finance minister were strong advocates for a yes vote and threatened that the alternative would attract stiff penalties (Walter et al. 978). In addition, foreign policymakers interfered with the campaigns. This was evidenced by the Eurozone’s finance ministers’ decision not to extend the ongoing bailout program after the referendum date was announced, despite the fact that the program was scheduled to end three days later (Walter et al. 978). The Emergency Liquidity Fund, which was intended to provide funds meant to keep the Greek banking system functioning was terminated on the basis that the absence of a bailout program made the endeavor untenable (Walter et al. 978). The Greek authorities were forced to call a bank holiday and impose capital controls in a bid to control the unfolding crisis (Walter et al. 978). Despite the nation’s fragile economy, a poll before the referendum demonstrated that the voters were defiant of the existing arrangement (see table 1).

The events preceding the Greek referendum demonstrated the Eurozone’s determination to ignore the Greek government’s anti-austerity mandate. The economic damage that occurred as a result of the Eurozone’s interference increased the quantity of resources required for an economic bailout. Initial estimates indicated that Greece would need between 30 and 59 billion Euros to help revive its economy (Walter et al. 979). However, after the Eurozone’s interference in the referendum, the Greek economy needed 90 billion Euros to address its devastating economic situation (Walter et al. 979). The highlighted events demonstrate the flaws in the European Union’s systems.

Table 1: 2015 Greece Bailout Referendum: What do you think will be the consequences of a No vote?

The Exit’s Benefits to Citizens

It is worth considering the fact that if the Greeks had their own currency, it would have dealt with its financial recession through devaluation and looser monetary policies. This would have made a majority of Greek exports more competitive. The resultant prioritization of local purchases as opposed to imported products and the increase in tourism would actively reverse capital flight. Greece is, however, unable to implement the aforementioned measures because of the confines of the European Union’s laws. There is no argument as to the fact that the Greeks would have had to implement difficult structural and austerity reforms. However, having their own currency would have aided in their recovery efforts. The Greek people would then be in a position to take advantage of the economic opportunities such measures would present. In addition, the outflow of Greek experts would be curtailed, and the economic recovery measures would allow the nation to provide a decent living for its people.

Conclusion

The European Union’s defective systems and inaccurate promises are the basis upon which Greece should base its arguments for a quick exit from the union. Greece’s departure from the Eurozone would undoubtedly cause damage to the economy. It is likely that the nation would experience unemployment, contracts would have to be re-written in order to reflect the newly adopted currency, and tax collection would be a herculean task. It is worth noting, however, that short-term inconveniences must not detract from the long-term benefits of leaving the European Union.

Works Cited

Lim, Darren J., et al. “Puzzled out? The Unsurprising Outcomes of the Greek Bailout Negotiations.” Journal of European Public Policy, vol. 26, no. 3, 2019, pp. 325–43, Web.

Raudon, Sally, and Cris Shore. “The Eurozone Crisis, Greece and European Integration: Anthropological Perspectives on Austerity in the EU.” Anthropological Journal of European Cultures, vol. 27, no. 1, 2018, pp. 64–83, Web.

Walter, Stefanie, et al. “Noncooperation by Popular Vote: Expectations, Foreign Intervention, and the Vote in the 2015 Greek Bailout Referendum.” International Organization, vol. 72, no. 4, 2018, pp. 969–94, Web.