Introduction: Evaluation of the campaign

The leaflet is part of the Change4Life campaign, which falls under the Department of Health portfolio. It is a public health campaign designed to tackle the problem of obesity in the UK through promotion of active lifestyles and healthy eating habits among children. Users include mothers, fathers, children who are at risk of obesity. If they signed up in the campaign, they would receive guidance on meal choices and learn how they can structure their exercise regimen.

Additionally, they can meet other households doing the same and motivate each other. This campaign will help users lose weight and thus minimise their susceptibility to obesity-related illnesses like cancer and diabetes. Interested parties can find more information from the Change for Life website.

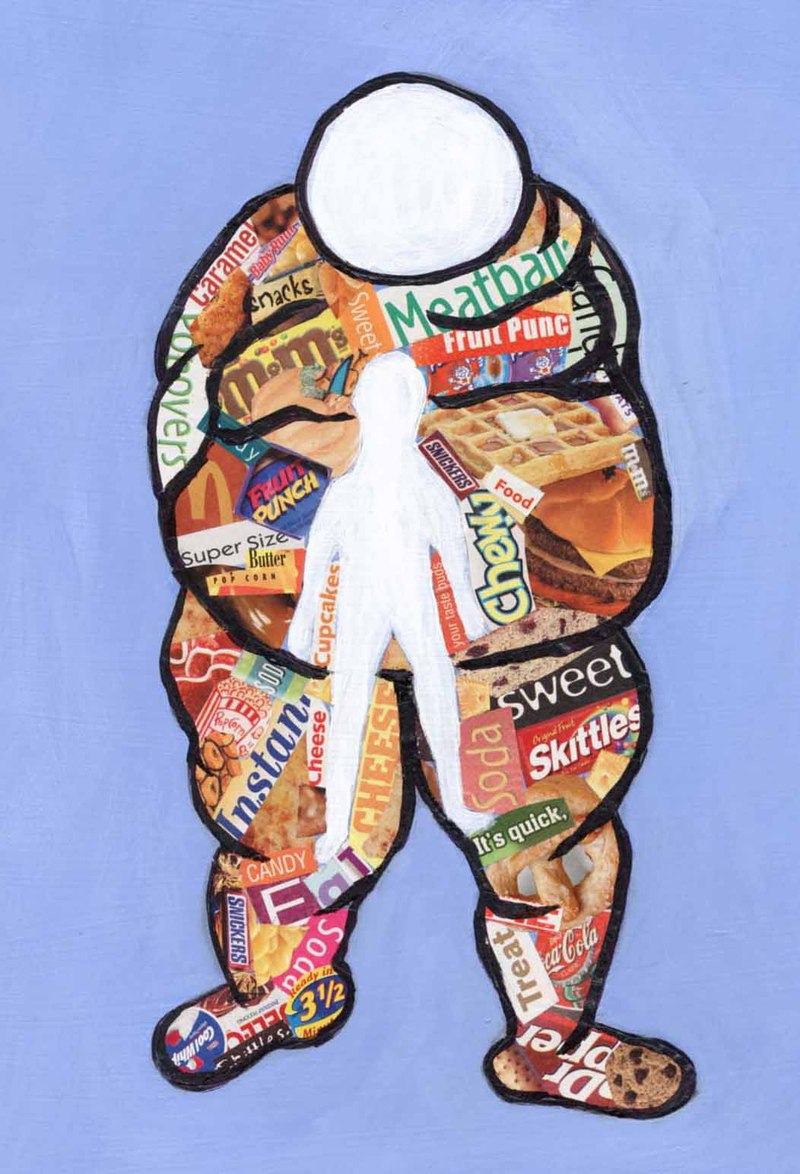

The first and most striking component of the campaign is its capacity to grab one’s attention. The image in the A4 leaflet is typical of others in the Change for Life Campaign. It makes creative use of images and words to bring the point across. In this promotion, many people will stop and think about how the food choices they make affect their propensity to add weight.

Words in this poster advertisement are quite suitable for their purpose. At first glance, one is likely to notice words with large fonts like ‘sweet’, ‘eat’, ‘Instant’, ‘chewy’, ‘treat’ and ‘meatballs’. Thereafter, one is likely to notice popular junk food labels like Coca Cola, Skittle’s, Cheese, Dr. Pepper, and Mom’s. Smaller fonts represent names of unlabelled foods like soda, food, cupcakes, supersize. This creative play with fonts allows readers to move their eyes through the poster and find different things that speak to them. They are more likely to remember the brands with the big fonts, and this can help them to stay away from these choices in the future.

Perhaps the most vital aspect of this advertisement is the content. The advert is clear, precise and uses very minimal words. This choice relates to the popularity of featured foods. In fact, the designer of the advertisement has taken care to represent almost all unhealthy food groups. Sugary foods or items that are high in sugar are represented in the form of snickers, cupcakes, cookies, candy and fruit punch. The word ‘sweet’ sums up this food group. In a campaign against unhealthy nutrition, one must acknowledge that sugary foods are key culprits, so they have to be mentioned. Additionally, some foods are high in unsaturated fat, such as meatballs, hamburgers, butter, cheese and other deep-fried treats.

This is, perhaps one, of the biggest contributors of obesity because such foods are packed with calories. One only needs to take a small quantity of the items before one suffers from the detrimental effects of obesity.

In terms of the content, the information provided in the poster also points out to some of the lifestyle choices that tempt people into buying unhealthy foods. Phrases like ‘it’s quick’, ‘instant’ and ‘supersize’ all denote a certain lifestyle that supports poor food choices. People go for junk food because it is easy to consume. They provide instant satisfaction and prevent consumers from having to spend too much time in the kitchen. Usually, these terms denote laziness and a sedentary lifestyle. The poster leaflet was vital in the campaign because it addresses the mindset that causes buyers to make their food choices.

The A4 leaflet is part of the Change for Life campaign, which has had tremendous success throughout the country. According to Piggin (2012), one million mothers claim that the Change for Life messages caused them to alter their families’ activity levels as well as their eating habits. Hardy and Asscher (2011) & Gemma (2011) reported that preliminary results showed that 30% of the target population (mothers) already felt that the campaigns was changing at least one thing in their diet.

Discussion

The Change for Life campaign has been quite successful due to its emphasis on scientifically-backed strategies. Macfarlane & Thomas (2010) explain that exercise alone is insufficient to cause weight loss. Changing one’s lifestyle from sedentary to active may take a period of two years to bring visible results. Weight loss percentages per week are unimpressive, and so is the overall weight loss. Therefore, campaigns that only focus on physical exercise will not be sufficient to tackle the problem of obesity. On the other hand, dietary changes have a dramatic effect on weight loss efforts.

A person can lose approximately 36 kilos in the period of one year if they only focused on dietary restrictions. Nonetheless, this strategy alone is insufficient in causing permanent weight loss. People who only focus on low-calorie diets are bound to gain back the weight they lost in the long term. This occurs because low-calorie diets reduce a person’s basal metabolic rate. Therefore, the body stores up the little food one consumes.

Only a public health campaign that urges consumers to live active lifestyles and engage in dietary restrictions works (Macfarlane & Thomas 2010). The two ideas (healthy food choices and exercise) must go hand in hand. The Change4Life campaign advocates for both these concepts. However, the promoters prefer not to tackle both issues at the same time. They often separate messages on diet and health into different campaign platforms. At the end of the day, the combination of both messages still gets to the people that matter.

Success also emanated from clearly defined problems and goals. Prior to the launch of the campaign, the promotional team realised that most parents in the UK know that obesity is an issues, but few take ownership over it. Some were unaware of the extent to which their lifestyle and dietary choices were dangerous. They poorly classified unhealthy habits and barely dwelt on long term issues (Hardy and Asscher 2011).

Therefore, the goals of this campaign centred on these issues. The team wanted families to recognise the risk of their decisions and take responsibility for it. They also wanted to prompt them to change and show them how to do it. By outlining some of the foods that the groups can use and how to structure their eating day, they sensitized the public on how to change work habits. Even their selection of psychical activities was in tandem with these goals (Department of Health 2010).

This campaign‘s success was partially compromised by the practical challenges of adopting a healthy lifestyle. The promoters partnered with local stakeholders in order to support consumers when making these choices. It is not sufficient to enlighten citizens about the dangers of junk food; one must also highlight the healthy options and provide information on how to access them. Many health campaigns have failed because they did not outline the quantity and type of product that is needed to maintain healthy lifestyles.

Fortunately, the Change for Life campaign incorporated this aspect quite substantially. One of its key pillars is the five-a- day strategy, which recommends five, eight-gram portions of vegetables and fruits daily. Such information not only clarifies the quantity of healthy foods one must take in order to eradicate obesity, but it specifies the frequency in with which must take them. The only problem in this approach is poor execution of partnerships with convenience stores. Adams et. al. (2012) carried out an analysis of partner organisations in the Change for Life convenience store partnership program. They analysed these convenience stores in low-income areas of North East England.

The researchers found that the partner convenience stores still sold most of the fruits and vegetables at higher prices than non partner supermarkets. Sometimes, prices were as much as 10% higher in those promotional stores. Residents in low-income areas are highly sensitive to price, and will forgo a product if it is expensive. As a result, most of the subjects under analysis did not purchase the healthy items. This was a symptom of poor communication between promoters of the campaign and retail stores. If a campaign team does not explain its intention for partnering with a food distributor, then it will not get positive results from the campaign. Failure to provide incentives for the implementation of healthy foods minimised consumers’ fidelity to the program in low-income areas.

The campaign decided to promote its message using friendly gestures, and this can explain why it did so well. Several advertisements consisted of cartoon-like characters that were initially practising healthy behaviour but later switched to unhealthy choices, or vice versa. This tone was friendly and non confrontational; it also represented a substantial portion of the campaign. However, some advertisements defied this logic. One case in point was a poster image of a girl eating a cupcake. It warned against early death due to these choices. Some individuals felt offended by the message because they felt that the Department of Health was trying to lecture them.

Market research as reported by Piggin (2012) points out that the days of government paternal behaviour are long gone. Consequently, social marketers need to think of their target markets as equals rather than subordinates. The message was abrasive because it appeared to point fingers at parents, yet they did not want this judgmental attitude. The Department of Health might have received even better responses if it maintained the friendly and fun-filled tone throughout its campaign advertisements.

A number of choices in the campaign have been quite controversial. This may have compromised the quality and outcome of the promotion in certain instances and enhanced it in others. Recently the Department of health banned the use of the Change for Life logo on branded products (The Marketing Society Forum 2010). Some brands had started using the product on the product packages, and this contradicted the message in the campaign.

It would cause confusion among food purchasers because they would assume that Change for Life approves the product. If the public found out that some of the brands using this product were not selling healthy items, then the realisation would hurt the campaign. Not all experts agree with this logic; they claim that if large brands used the campaign’s logo, then a wide pool of consumers would be reached by Change for Life.

Supporters argue that buy-in from key retail brands helps the campaign to save on marketing costs as the large companies would do it for them. Clearly, both sides have valid points. However, the Department of Health only wanted a campaign that would reflect the values of the initiative. Choosing to ban those powerful brands from using their logo was a correct decision that preserved the credibility of the campaign.

Another controversial aspect of the campaign was access to funding from commercial companies. Estimates indicate that the campaign group received approximate £200million from such donors (Editorial 2009). Typical firms include Kellogs and Pepsi. Critics have asserted that the campaign contradicted its messages by accepting funds from the same organisation that lead to the problem in the first place. If the campaign team wants to sound genuine, then it needs to liaise with organisations that adhere to social marketing principles. This decision was an oversight on the part of the campaign and should have been re-examined prior to its commencement.

When one analyses the impact of a campaign, one must look at it from a social marketing stand point. Some key aspects in the campaign explain why it did so well in the UK. Consumer research is one of the critical components of success in any marketing campaign. Although it was stated earlier in the report that adherence to scientifically-backed messages is a key component of success in social marketing campaigns, one must acknowledge that market research also plays a critical role.

If these two areas contradict each other, then market research should carry the day. Science states that marketers ought to combine dietary-restriction messages with active lifestyle messages. However, market research analyses of obesity campaigns have shown that if one combined diet and exercise in the same message, then mothers will pick one message over the other. Consequently, the team established that it is better to separate these messages. The campaign indicates that other factors may come into play when making decisions about lifestyles, so they need to be considered (Piggin 2012).

The campaign also yielded substantial outcomes because it emphasised the importance of agency in the manifestation of a public health problem; obesity. When tackling health concerns, some experts may blame community systems for the problem. For instance, one may state that the dominance of road transport increases sedentary lifestyles. However, this does little to prompt parents to change their lifestyles. Messages must refrain from laying blame on amorphous factors and focus on living subjects. Such was the case for the Change for Life campaign as it targeted mothers who make food choices and have the capacity to encourage or discourage their children from exercising (Piggin 2012).

Conclusion

Overall, the campaign was successful since it had a high number of sign-ups. This success stemmed from reliance on scientifically-backed materials, clear goal identification, user definition, and prioritisation of market information over theoretical findings. The campaign team was audacious enough to ban the use of the logo by branded products. Its emphasis on agency, as a cause of obesity, was also a laudable tactic.

Conversely, the campaign could have realised even more successful outcomes if it did not partner with commercial companies that sell unhealthy products. The Department of Health did not collaborate with convenience stores appropriately, and this compromised the accessibility of health foods. Additionally, it should have maintained a friendly tone throughout the campaign. Change for Life would have recorded even greater numbers if it ironed-out these glitches.

References

Adams, J, Halligan, J, Watson, D, Ryan, V, Penn, L, Adamson, A & White, M 2012, ‘The change for life convenience store programme to increase retail access to fresh fruit and vegetables: A mixed methods process evaluation’, Plos One, vol. 7 no. 6, pp. 1-7.

Department of Health 2010, Change4Life one year on. Web.

Editorial 2009, ‘Change4Life brought to you by PepsiCo’, The Lancet, p. 96.

Gemma, C 2011, ‘Change for life wins approval’, Marketing, p. 3.

Hardy, A & Asscher, J 2011, ‘Recipe for success with Change4Life’, Market Leader, Quarter 1, p. 24-27.

Macfarlane, D & Thomas, G 2010, ‘Exercise and diet in weight management: Updating what works’, British Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 44 no. 16, pp. 1197-1201.

Piggin, J 2012, ‘Turning health research into health promotion: A case study of causality and critical insights in a United Kingdom health campaign’, Health Policy, vol. 1107 no. 14, pp. 296-303.

The Marketing Society Forum 2010, ‘Is it right to stop brands using Change4Life imagery on-pack?’, Marketing Society, p.30.