Overview

Chronic pain is a foremost health concern among the elderly, both in the community setting and within care institutions. Regrettably, most health conditions afflicting older people are relatively painful and chronic in nature, such as arthritis, back pain, prostate enlargement, osteoporosis and post-fracture complications, and this group of the population is often faced with more than one source of pain (Gudmannsdottir & Halldorsdottir, 2009).

A number of studies have adduced compelling evidence that pain in old age has been considerably under-diagnosed and under-treated in large part due to inconsistencies in patients’ and care providers comprehension of the causes of pain. The health needs of older people in the management of chronic pain are further compromised by self-assessment methodologies used by patients to describe pain in addition to the assessment done by nurses and doctors, which may end up underestimating the pain (Maly & Kropa, 2007). Hopkins et al (2006) is of the opinion that self-assessment of health is not easy to evaluate objectively since it is related to an individual’s perception of their life’s quality.

Health as a concept is multifaceted, and applied implications cannot be comprehended without taking into consideration the social and cultural backgrounds in which we live out our lives (Hopkins et al., 2006). If health is socially and culturally constructed, then perspectives and perceptions are bound to vary, shifting with age and circumstances.

Previous studies have demonstrated that men, racial minorities, the disabled and cognitively impaired, and individuals over 85 years of age stands an elevated risk of being under-diagnosed, largely due to issues of inconsistencies in understanding, gaps in self-assessment, individual perceptions and perspectives held by society (Gudmannsdottir & Halldorsdottir, 2009; Jakobsson & Hallberg, 2002). A study conducted in 2000 by Bernard and colleagues revealed that “…older people tend to view health in functional terms, emphasizing the importance of resilience and of being able to cope, rather than fitness” (Hopkins et al., 2006).

Older people suffering from conditions that cause acute pain may draw on a more holistic account of their health and wellbeing, one that is largely related to the quality of life or self-esteem (Oliver, 2009), or a prejudiced assessment of their present state in terms of mood and happiness (Hopkins et al., 2006). In addition to chronic pain, some conditions such as osteoporosis and arthritis may cause frailty and disability among the elderly, a scenario that alters their perspectives towards health.

A study by Weitzenkamp and colleagues revealed that disabled individuals altered many of the standards against which they assessed their wellbeing (Hopkins et al., 2006). According to Gudmannsdottir & Halldorsdottir (2009), the elderly can themselves be a block to professional assessment and management of the conditions by nurses and doctors by concealing their pain for some reason or by prematurely resigning to the pain due to the perception that pain unavoidably increases with age.

Hence, it becomes difficult for external assessors to classify the nature and scope of an illness affecting an elderly person without a proper grasp of how health terms are conceptualized, comprehended or experienced (Hopkins et al., 2006). As such, it is imperative for care providers to gain a comprehensive insight into the lives of the elderly, to focus on the experience of living with conditions that cause acute pain, and to explore their perspectives by not only talking to them but also sharing in their experiences (Hyde at al, 1999).

It is against this backdrop that the present study aims to fill the knowledge gap that exists on how to objectively assess the health needs of the elderly living with conditions that cause acute pain from their own experiences and perspectives. Specifically, the study will aim to assess the experiences and perspectives of older people living with arthritis.

Aims of Study

The study generally aims to critically evaluate the lived experiences of older people suffering from arthritis using the phenomenology methodology to gain a comprehensive insight into their lived experiences. The following are the specific objectives:

- To develop a better understanding of how the lived experience of the elderly can be used by nurse professionals and doctors to avail interventions aimed at improving the quality of life of patients, both medically and psychologically

- To gain a deeper understanding of how lived experience affects or influences the self-assessment methodologies used by the elderly in seeking healthcare assistance

Research Question

The study will be guided by the research question: What is the lived experience of older people suffering from arthritis?

Justification of Study

Arthritis is known to occasion a significant health burden to populations and health institutions worldwide, but little is known of the lived experience and the impact on the quality of life of the sufferer (Oliver, 2009). Some forms of arthritis such as rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis mainly affect the elderly, causing anguish and pain in addition to limiting their mobility and ability to go about their most basic obligations (Jakobsson & Hallberg, 2002).

As demonstrated by Hopkins et al (2006), previous studies have found that this group of the population is most at risk of under-diagnosis and under-treatment due to a number of reasons, including subjective self-assessment, perception issues, concealment of pain, and premature resignation to fate. To assist this group, there is immediate need to critically evaluate the lived experience in the hope of identifying their perceptions and coping strategies, which can then be integrated into the existing treatment and management practices for arthritis to provide a holistic intervention and improve the quality of life of sufferers. Studies have also shown that older people are at a higher risk of being affected by various forms of arthritis (Jakobsson & Hallberg, 2002) and, as such, knowledge about the older people’s lived experience is critically important in the management of these conditions.

Methods

Introduction

This section purposes to discuss the methods used to evaluate the lived experience of older people suffering from arthritis. Specifically, the section will report on the study design, data collection techniques, ethical considerations, data analysis, and the limitations of the methodology and methods used.

Research Design

To gain a deeper understanding and thorough insight into the lived experience of the older people, this qualitative study utilized phenomenology as the primary methodology. Traditionally, studies into chronic illness have employed a quantitative research design to evaluate issues relating to quality of life, motivation and life satisfaction, capacity to cope with the condition, resilience, control, hope, compliance, apprehension, depression and social support (Hyde et al., 1999).

The authors are of the opinion that such quantitative studies tend to be “…reductionist in method and result in data that exclude lived experience” (p. 190). To better understand an individual’s objective and subjective accounts of living with a chronic illness, Mary & Kropa (2007) advise that it is better to perform a qualitative study, which extends to participants the opportunity to express their personal views and experiences in their own way.

Phenomenology

The phenomenology approach takes into account that certain facets of human life cannot be evaluated in the same manner as components of the physical world (Carson & Mitchell, 1998). Since the main aim of the study was to get a deeper insight into the lived experience of older people suffering from arthritis, from their own viewpoint, phenomenology was selected as the methodology of the study due to its capacity to give the phenomena under study a fuller, comprehensive, and fairer hearing than what can be accorded by traditional empiricism (Gudmannsdottir & Halldorsdottir, 2009). The phenomenological approach is particularly determined to undo the effect of habitual prototypes of thought.

There exist many schools of thought within the phenomenological approach, but this study utilized The Vancouver School of doing Phenomenology in the hope of adequately answering the key research question and the study objectives. According to Halldorsdottir (2000), this approach utilizes an interpretive constructivist phenomenological orientation, thus is exceedingly helpful when the targeted belong to a vulnerable group as is the case in this study, which targets the elderly people. Additionally, this school adapts well to the needs of this study because it not only refers to participants as persons but greatly emphasizes their lived experience.

Gudmannsdottir & Halldorsdottir (2009) states that the Vancouver School views participants as “…co-researchers as they are the experts in their own experience and the interview is seen as a research dialogue resulting in a mutual construction of reality which otherwise might have been hidden” (p. 319). More importantly, this approach is considered effective when dealing with the elderly since experience has demonstrated that this group of people needs ample time and always prefer to express their experiences in a subjective and open manner (Carson & Mitchell, 1998).

Data Collection

The study used an in-depth interview schedule to collect pertinent data on the lived experience of older people suffering from arthritis. It is imperative to describe in brief some of procedures undertaken prior to the actual data collection exercise

Sampling

Sampling was purposive since the study was interested in evaluating a specific group of the population suffering from a particular condition (Hyde et al., 1999). Purposive sampling – also known as judgment sampling – fits the focus of this study because the technique has the capacity to provide information-rich cases for in-depth study. Whitehead & Annell (2007) argues that “…purposive sampling occurs when the researcher selects people who have the required status or experience, or who are endowed with special knowledge, to provide the researcher with vital information they seek” (p. 124).

Criteria for Selecting Participant

The criteria was that:

- participant must be at least 75 years of age and above;

- participant must have lived with the arthritic condition for a period of not less than 12 months;

- participant suffered at least some ‘moderate’ or ‘persistent’ pain according to own self-assessment or estimation;

- the pain did interfere with the participant’s daily life and interactions, by nurses estimation;

- be of either sex and able to communicate adequately

Gaining Access to Participant

Having obtained the needed authorizations, a letter was sent to the director of nursing to arrange a meeting with the relevant head nurse. In the meeting, the main aim of the study was introduced and the cooperation of ward nurses sought, especially in identifying a participant who met the standards for selection. At this stage, the head nurse advised that it was resourceful to select a female participant because elderly men seem to be less expressive about their conditions. Lastly, a 78 year-old woman with osteoarthritis was identified, and she voluntarily agreed to take part in the in-depth interview.

In-depth Interview

A semi-structured in-depth interview was used to assess the lived experience of the elderly participant suffering from osteoarthritis. The Family Health International (n.d.) describes the in-depth interview as “…a technique designed to elicit a vivid picture of the participant’s perspective on the research topic” (p. 29). The interview was designed to last 30 minutes, and was structured in a way that gave the researcher the leverage to pose the questions contained in the interview guide in any order provided they were asked in a neutral manner.

The technique obliges the researchers to listen attentively to the responses given by participants, and pose follow-up questions, clarifications and probes based on those responses (). The researchers, according to Gladhill et al (2008), should not direct participants according to any predetermined perceptions, nor should they persuade participants to present particular responses by openly demonstrating approval or disapproval of what they say. It is imperative to note that the in-depth interview was face-to-face, involving the researcher and the participant.

There are a number of reasons why in-depth interview was selected as the primary data collection technique. In-depth interview synchronizes well with the phenomenological approach by virtue of the fact that the participant is considered as the expert in the study, and both approaches are directed by the desire to learn more about the participant’s experiences related to the research topic (Gladhill et al, 2008).

In addition to being recognized as the prime technique for qualitative data collection especially in nursing-related research (Whitehead & Annell, 2007), it was generally felt that the procedure will enable the researcher to gain a deeper understanding and insight into the participant’s lived experience and expose the subjective meanings that may be linked to the condition from the participant’s viewpoint. In-depth interviews also provide the interviewer a chance to probe further to gain an ever deeper insight of the real issues under study (Whitehead & Annell, 2007), a factor that is inarguably critical in evaluating the lived experience of older people suffering from arthritis.

The Interview Guide

[Initial greetings and asking the participant where she comes from to break ice]

- How many years have you lived with this condition [osteoarthritis]

- If you can recall, what were your initial reactions when the condition was first diagnosed

- if you can recall, what were the initial reactions of close family members and relatives when they learnt of your condition

- What does it mean to you to have arthritis?

- How has the pain associated with your condition affected your daily interactions and lifestyle over the past six months?

- What individual interventions do you employ to manage the chronic pain associated with your condition?

- How has your age influenced you in the management of this condition?

- I know you have received a number of medical interventions over the course of this condition. How have they assisted you to manage the condition?

- What changes in your life have been made or will have to be made to accommodate your condition?

- What, in your opinion, do you believe will happen in the future?

The responses were audio-taped after the researcher requested for permission from the ward nurses and the participant. According to Hyde et al (1999), recording the conversations not only enhances the quality of the data obtained from the participant, but gives the researcher adequate time to listen to the participant’s side of the story and also note the strong points from observing the non-verbal cues presented. Such information would be missed out if the researcher engages in writing down responses as opposed to recording. In addition, recording the responses quickens the interview process, an important factor when dealing with frail elderly people by virtue of the fact that they get tired quickly (Maly & Krupa, 2007; Spiegelberg, 1983)

Ethical Considerations

Many qualitative studies in the nurse practice involves the use of human subjects, hence the need to ensure conformance to ethical principles (Minichiello et al., 2008). Approval for the study was obtained through the research ethics committee of the health facility, and the hospital administrator, head nurse, and the ward nurses were briefed about the nature and scope of the study. The participant was also detailed about the purpose of the study, and permission was sought from the hospital administration as well as the participant to audiotape the conversation. The participant was also detailed on the confidentiality clauses and withdrawal to ensure consent to take part in the interview was voluntarily informed.

The first principle in the Nuremberg Code is very clear about the essentiality of voluntary consent in dealing with human subjects (Coup & Schneider, 2007). The participants must not only be given the legal capability to voluntarily give consent, but they must be offered the capacity to understand the information provided so as to make an informed consent.

Data Analysis

It is important to note that the study adopted the Vancouver School of doing Phenomenology as the primary methodology in order to gain a deeper insight and understanding into the lived experience of older people suffering from arthritis. According to Halldorsdottir (2000), the school “…espouses a world that is made up of meanings, which profoundly affect how people experience and live their lives” (p. 47).

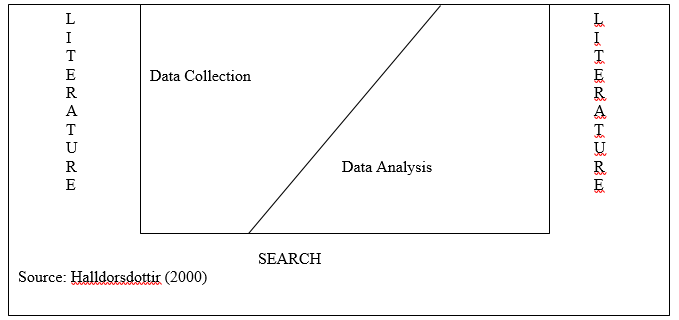

As such, one of the primary objectives of data analysis using this school of phenomenology is the production of the reconstructed understandings of the phenomena under study from the point of view of the participant, who is largely referred to as a co-researcher. The research methodology, therefore, “…involves the cyclic process of silence, reflection, identification, selection, interpretation, and verification” (Halldorsdottir, 2000, p. 47). In this school of phenomenology, the process of data collection and data analysis runs concomitantly, though both processes are presented separately. The figure below demonstrates how the school is operationalized.

Although the Vancouver School of doing Phenomenology follows some 12 basic steps (Halldorsdottir, 2000), this section will only involve itself in the steps that are pertinent to the process of data analysis, and how they were applied in this study. These steps include: sharpened awareness of words (analysis); coding; constructing the fundamental structure of the phenomenon for each case; and identification of the overriding themes which comprehensively describes the phenomenon (Halldorsdottir, 2000; Maxwell, 2005).

All the conversations involving the researcher and the (participant) were audio-taped and then transcribed verbatim through processing all words on a computer (Fielding & Lee, 1993). The sharpened awareness of words step involved reading and rereading the transcribed conversation to get a sense of the participant’s lived experience as a whole. According to Halldorsdottir (2000), the researcher should first read the transcript as an exiting novel to acquire a deeper feeling for the protocols and make sense out of them, letting the data “…soak in by being as receptive as possible, listening attentively to the dialogues and reading the transcripts attentively” (p. 62). This should always be done with an open mind.

In the coding step, the researcher first identified key statements made by the participant and which had a special bearing on the phenomena under study – the lived experience of older people suffering from arthritis. Afterwards, themes of key statements were identified and coded by writing the names on the right side column of the transcribed interview (see appendix 1). According to Halldorsdottir (2000), this is a step in the Vancouver School of doing Phenomenology specifically oriented to identify the essences of the phenomena

The third step, involving constructing the fundamental structure of the phenomenon for each case, was simplified since the in-depth interview was only administered to one participant. However, the researcher used this phase to group similar themes into one category so as to get a clearer picture of the phenomena under study. Finally, the researcher undertook to identify overriding themes which described the phenomena under study so as to gain a deeper insight into the issues that were of fundamental importance to the study (Halldorsdottir, 2000). The underlying themes and associated meanings were then formulated into analytical findings that could be used objectively to explain the lived experience of older people suffering from arthritis

Brief Synopsis of Findings

Findings

The findings of this particular study are presented in the table below, stated according to the underlying themes and related clusters of meaning for ease of understanding

Experiencing pain is a central component to osteoarthritis experience

- Pain is more bearable when an individual can anticipate its end, or when one has a sense of control over the pain

- Pain caused by arthritis causes one to slow down

- Pain caused by arthritis decreases level of confidence and trust on self

Functional and mobility limitations devalues self-worth

- Having a functional or mobility challenge devalues one’s sense of self-worth since mobility is an integral component of self-identity

- Mobility transformations arising from chronic pain makes an individual to become conspicuous to others that he/she experiencing poor health

- The sensation of stiffness caused by arthritis impairs one’s capacity to move freely

Sharing the experience of living with arthritis

- Experiences of others suffering from the same condition influence perceptions, opinions and decisions, not mentioning that such experiences provides information

- Sharing experiences with others offer meaning for enduring hardship and chronic pain

Assessing own Health

- Comparisons are made at different points in time and with others suffering from the same or similar condition to assess performance, health, and wellbeing

- Trust in the doctor/nurse – patient relationship results when the provider’s evaluation of the patient’s status reflects his/her feelings

Managing Chronic Pain

- Knowledge regarding management of pain is particularly gleaned from peers and social support systems, rather than nurses and physicians

- Excessive pain decreases the quality of life

- Excessive/chronic pain is positively correlated to depression

- Physicians offer passive treatment methodologies, not active management approaches, to live with persistent pain

The Experience of Age

- Older people have strong coping mechanisms that may confuse healthcare professionals about the extent and scope of pain

- Chronic pain increases with age, and this increases feelings of worthlessness

Discussion

A meta-analysis done by Jakobsson & Hallberg (2002) on the lived experience of the elderly people suffering from chronic pain found that not only did the functional limitation continued to worsen with disease duration and age, but also anxiety and depression continued to increase with disease duration. The analysis also revealed that pain was one of the most upsetting challenges among the elderly living with rheumatoid arthritis, and it tended to increase with age and disease duration.

The findings of the present study collaborates these facts. A study conducted by Beitz et al (2005) on the lived experience of having a chronic wound revealed that dependence on others, lack of social support, and negative spouse/relative behaviour such as avoidance and critical remarks exacerbated pain, not mentioning that these factors decreased the quality of life and wellbeing of sufferers. In addition, the study demonstrated a correlation between wellbeing and quality of life on the one hand and functional limitation on the other.

The present study has demonstrated that severe pain and age progression not only reduces vitality and social functioning, but it has underlined the importance of social support and understanding of the lived experience in the management of the chronic pain occasioned by arthritis. Therefore, it is critically important to have a deeper understanding of the lived experience of older people suffering from arthritis if effective treatment and management strategies are to be achieved (Hyde et al, 1999), and if the older people are to be assisted to have more satisfying lives.

Limitations of the Methodology & Methods

The credibility of qualitative research is to large extent dependent on the methodical skill, understanding, and integrity of the researcher (Halldorsdottir, 2000), especially in analyzing the subjective meanings and developing themes that can be used to adequately answer the phenomena under study (Grbich, 1999; Moon, 2004). This implies that the validity, trustworthiness, reliability of studies using the phenomenological approach is largely dependent on the skills, rigour and competence of the researcher, and therefore may be expensive to undertake since they require specialized skills (Halldorsdottir, 2000; Moon, 2004).

According to Grbich (1999), some phenomenological approaches have received criticism because of the fact that “…it may not be possible to suspend all empirical and metaphysical presuppositions about the world through bracketing” (p. 170). Still, access to concealed subjective meanings has also been challenging, as has the inclination for the approach to generate only shallow narratives of social phenomena.

As such, the interviewer must have the capacity to continually question the interpretation of subjective meanings or risk validity. Some researchers have also questioned the rationale of inter-subjective interaction between the researcher and the participant (Sokolowski, 2000; Manen, 1990), claiming that such interaction can be used to alter findings, therefore risking the reliability and trustworthiness of the study.

In terms of the methods used, Whitehead & Annell (2007) argues that in-depth interviews are not only time-consuming and resource-intensive to establish, but also encounter ethical challenges especially in questions which may seem biased, leading, manipulative or coercive. In addition, limitations may arise in “…securing access, making sensitive records, managing power relationships, managing space, managing communication, and managing sequelae of interviews” (Whitehead & Annell, 2007, p. 129).

Grbich (1999) & Reason (1988) notes that in-depth interviews require skills, competency and integrity to undertake, thus the risk of getting invalid results in studies undertaken by researchers who lack these competencies is a matter of concern. Purposive sampling, according to Gray et al (2003), has a potential for inaccuracy in the criteria used to select the sample used for the study.

Reference List

Beitz, J.M., Goldberg, E., & Voder, L.H. (2005). The lived experience of having a chronic wound: A Phenomenological study. MEDSURG Nursing, 14(1), 51-82. Web.

Carson, M.G., & Mitchell, G.J. (1998). The experience of living with persistent pain. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 28(6), 1242-1248. Web.

Coup, A., & Schneider, Z. (2007). Ethical and legal issues in research. In Z. Schneider, D. Whitehead, D. Elliot, G. Lobiondo-Woed & J. Haber (Eds.), Nursing & midwifery research: Methods and appraisal for evidence-based practice 3rd Ed. Marrickville, NSW: Elsevier Australia.

Family Health International. (n.d.). Qualitative research methods: A data collector’s field guide. Web.

Fielding, N., & Lee, R.M. Using computers in qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Flynn, J.A., & Johnson, T. (2006). Arthritis 2006. Arthritis, 1-90. Retrieved from Health Source – Consumer Edition Database.

Gladhill, S., Abbey, J., & Schweitzer, R. (2008). Sampling methods: Methodological issues involved in the recruitment of older people into a study of sexuality. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 26(1), 84-94. Web.

Gray, P.S., Williamson, J.B., & Karp, D.E. (2003). The research imagination: An introduction to quantitative and qualitative methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Grbich, C. (1999). Qualitative research in health: An Introduction. CrowsNest, NSW: Allen & Unwin.

Gudmannsdottir, G.D., & Halldorsdottir, S. (2009). Primacy of existential pain & suffering in residents in chronic pain in nursing homes: A phenomenological study: Scandinavian Journal of Caring Services, 23(2), 317-327. Web.

Halldorsdottir, S. (2000). The Vancouver school of doing phenomenology. In B. Fridlund & C. Haldingh (Eds.), Qualitative research methods in the service of health. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Hopkins, A., Dealey, C., Bale, S., Defloor, T., & Worboys, F. (2006). Patient stories of living with a pressure ulcer. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 56(4), 345-353. Web.

Hyde, C., Ward, B., Hursfall, J., & Wider, G. (1999). Older women’s experience of living with chronic leg ulceration. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 5(4), 189-198. Web.

Jakobsson, U., & Hallberg, I.R. (2002). Pain and quality of life among older people with Rheumatoid Arthritis and/or Osteoarthritis: A literature review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 11(4), 430-443. Web.

Maly, M.R., & Kropa, T. (2007). Personal experience of living with knee osteoarthritis among older adults. Disability and Rehabilitation, 29(18), 1423-1433. Web.

Manen, M. (1990). Researching lived experience: Human Science for action sensitive pedagogy. New York, NY: State University of New York Press.

Maxwell, J.A. (2005). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Minichiello, V., Aroni, R., & Hays, T. (2008). In-depth Interviewing, 3rd Ed. Sydney: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

Moon, J. (2004). Handbook of reflective and experiential learning: Theory and practice. London: Routledge.

Oliver, S. (2009). Understanding the needs of older people with Rheumatoid Arthritis. The role of the community nurse. Nursing Older People, 21(9), 30-37. Web.

Reason, P. (1988). Human inquiry in action. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Schroeder, J. (2010). Arthritis: So many types, so much to learn. American Fitness, 28(1). Web.

Sokolowski, R. (2000). Introduction to phenomenology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Spiegelberg, H. (1982). The phenomenological movement, 3rg Ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Whitehead, D., & Annell, S.M. (2007). Sampling data and data collection in qualitative research. In Z. Schneider, D. Whitehead, D. Elliot, G. Lobiondo-Woed & J. Haber (Eds.), Nursing & midwifery research: Methods and appraisal for evidence-based practice 3rd Ed. Marrickville, NSW: Elsevier Australia.