My Neighbor Totoro, filmed in 1988 by famed animator Hayao Miyazaki, is one of the Iconic animated tales produced by Studio Ghibli and one of my favorite movies. This cartoon Embodies the main motives of Miyazaki’s work – childhood, the fidelity of friends, the dark side of the personality, and the power of fantasy. The film about Totoro needs to be analyzed to find out why it is a complex work with a lot of details.

The primary interpretive step is to limit one’s own judgment in order to avoid the Realization of internal prejudices. Personally, I am a big fan of animation. My experience tells me that some anime are very hard to follow due to their twisted plot, full of flashy flashes and over-the-top actions. However, this film does not have any of the above features, it is soft, restrained in pacing, and its animation is noble. The plot of the film is not only a children’s fairy tale but folklore about a fabulous friend and a touching story, which can resonate with an adult audience. To be more specific, in the scene where Mei and Satauki find Totoro and tell this exciting news to their parents, instead of convincing them that this creature does not exist, they actually start their trip to find Totoro together. That is one of the happiest moments Mei and Satsuki have throughout the movie. The scene could play as a pathos as it affects the audience’s emotions positively.

The film begins with two sisters, Mei and Satsuki, moving into a private house in the Countryside with their father. Not far from it is a hospital where the mother of the girls is. The sisters accidentally find the keeper of the forest – Totoro, and not only him. In the course of the picture, they meet various fantastic creatures that help them cope with problems. For example, Totoro, together with the girls, performs a ritual that awakens the crops, or Catbus, who helps in the search for the heroine’s sister. The sisters in the film interact with things that cannot exist. Children are extremely realistic and detailed characters that fit seamlessly into different scenes. They scream, get lost, cry, feel ashamed over trifles, worry too much, and laugh for no reason.

In detailing his heroines and fantasy worlds, Miyazaki draws on a vast array of sources, Including myths, ancient Japanese legends, history, science fiction, and fairy tales. This can be seen in the film Totoro, which is filled with references both to the era of the samurai and to more modern culture. Miyazaki’s characteristic handwriting is that practically every frame contains aesthetic features that either hint at a phenomenon to the viewer or are necessary to convey the atmosphere. In any case, Japanese features are expressed even through small details, such as grass or trees, characteristic of the local climate. Finally, wooden utensils, sticks, hieroglyphs and silhouettes of clouds in the sky refer to a special and unique world that is instantly recognizable.

The most interesting aspect of the film for me was the unusual relationship that develops between a girl and a creature from a mythical space. The dynamics of their relationships constitute the emotional core of the film and provide the audience with interest. Japan is shown in this way as a land of mythical creatures and fairy-tale mysteries, which is the most revealing part of the film. The strangest aspect of the film, however, was the design of the creatures themselves (HBO Max Family, 2021). Miyazaki obeyed the principle of Japanese culture and transformed it by adding a unique element of childhood.

Furthermore, when examining the cultural value of ‘My Neighbor Totoro,” one must not overlook one of the central themes that the movie seeks to address. Namely, the fact that the film is actively emphasizing the importance of environmentalism and the significance of conserving nature must be mentioned. Indeed, research points out that the issue of preserving nature and safeguarding it from the harmful impact of urbanization and the related processes represents one of the essential ideas that Miyazaki seeks to convey: “We are returning to you something you have forgotten” (Mandal, 2022, p. 99). In turn, the specified notion is emphasized by the brilliant use of animation, the introduction of new plot developments, and the subtle hints in the behaviors and attitudes of the protagonist.

Indeed, considering the movie closer, one will recognize the scenes that point to the idea of respecting nature and striving to preserve it. For example, the scene in which the two sisters attempt to make the trees grow in the night by performing a series of elaborate bows and movements can be considered an example of demonstrating appreciation for nature (Miyazaki, 1988). Though the specified gesture could be considered slightly weird in the present-day cultural context, Mandal (2022, p. 99) explains that “My Neighbor Totoro” “takes the audiences back to a simpler time when everything appeared to be magic with its illusion surrounding life.” Therefore, in the environment of what the movie views as a simpler time, the specified ritual can be seen as an attempt at revving nature and reconnecting with it.

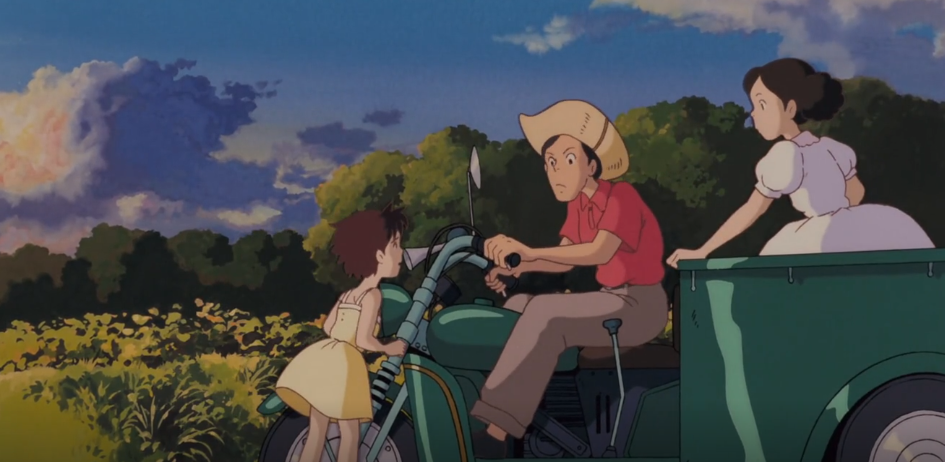

Moreover, the setting of the movie is highly indicative of the theme of environmentalism as one of the central ideas to be actively developed throughout the narrative. Apart from the rural context, which is a hint in itself, pointing directly to the notion of being environmentally aware, “My Neighbor Totoro” allows the viewer to explore the rural past of Japan. According to Mandal (2022), “the film also takes the audience back to a national past, seemingly untainted with the pollution showered in by the advent of globalization and the subsequent materialism” (p. 99). Indeed, the movie features few t no vehicles; the only mode of transportation most characters use is a bicycle. Specifically, the protagonist and her friend are seen on their bikes as the search for Mei starts. Arguably, some of the scenes feature the use of actual cars, particularly in part involving the search for Mei. However, the use of cars in “My Neighbor Totoro” is either reserved for agricultural purposes, with characters appearing on the vehicle evidently used for managing crops, or for purely utilitarian reasons. Therefore, the focus on returning to the earlier and simpler times that did not pose the same extent of the threat to the environment is evident in the movie.

Therefore, the significance of nature conservation is explained clearly yet subtly in the movie. As a result, the concept of environmentalism becomes palatable to audiences of all ages, ranging from young children to adults. Remarkably, the theme in question does not overshadow the main one, namely, that one of family and support, but instead, complements it. A mutual appreciation for nature and its significance remains the connective tissue that keeps the family together, along g with their love for each other. Given the context of the film, specifically the fact that the protagonists are facing significant challenges, with their mother being in the hospital, the development of a connection that is not linked to any emotionally devastating issues becomes particularly appreciated, allowing for certain lightheartedness.

Totoro is a fantastic animal, fluffy and very large, but at the same time, it does not pose a danger to children. The scene where the main character interacts with the sleeping Totoro proves that this creature should be perceived as a protector figure. The girl grabs his huge paw, and climbs onto the fluffy chest of the animal, but he is not at all annoyed, like a kindly older relative. Totoro is clumsy but symbolizes majesty; it causes adoration and a sense of reliability and security in the characters of the film (Napier, 2018). Indeed, Miyazaki shows through the friendship of the main character and Totoro that a person must be curious, kind, innocent, and connected with culture as with the organic fabric of life. Totoro is a creature from the forest, embodying nature, so his interaction with the girl means a search for kinship between a person and the world around them. Furthermore, from Miyazakiworld: A life in art, Napier brings us inside the Miyazaki universe and explains how Miyazaki drew inspiration from his own European experiences for many of the cinematic worlds he built, which provides an opportunity to explore and refine perspectives of Miyazaki’s movies and animations in general (Napier, 2018). This will support my argument that the creature is harmless and a protector figure.

One of the most beautiful scenes is the one in which the sisters wait in the rain at the bus stop for their father from work. They took two umbrellas, one for the eldest girl, and one for her father, and the youngest sister put on a raincoat. The agonizing expectation dumps the youngest; she literally falls asleep on the go. In order to drive away frightening thoughts or brighten up the longing to wait for the bus, Totoro comes to the bus stop with them. Totoro waits for Catbus, and his father arrives and the rain stops – the umbrella is no longer needed. The scene is deep in terms of the girls’ perceptions: waiting in the rain flows into clear weather and a long-awaited meeting.

Totoro is interesting to look at from a genre discussion point of view but at the same.

Time, the film’s involvement in the fantasy genre is even more interesting to explore from the perspective of how ambiguity is associated with the artistic depiction of characters in Miyazaki’s work. One of the most outstanding features of this portrait is that fiction allows young children to take care of their own mental state in a moment of stress and anxiety. Regardless of whether the viewer believes in a natural or supernatural explanation of what is happening, the characters have the ability to enter into contact with the unconscious.

One could ask questions about the additional motivations Totoro wonders why he never talks to the girl; although he understands her, it is what makes two kids see Totoro, but others cannot. A more detailed analysis probably would reveal that Totoro is not just a fabulous friend but the embodiment of a divine totem, a creature that must be treated with sacred awe. To be more specific, the showing of Totoro’s cat bus and the scene where their parents cannot see their kids. On the other hand, it could just symbolize warmth, innocence, and childishness. The entire mythology embedded in the film requires more detailed consideration.

References

HBO Max Family. (2021). My Neighbor Totoro | Mei meets Totoro (Clip)[Video]. YouTube.

Mandal, B. The Insertion of Cultural Identity and Ecological Recovery through a Critique of Materialism and Overconsumption in Spirited Away and My Neighbor Totoro. PostScriptum: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Literary Studies, 7(1), pp. 93-103.

Miyazaki, H. (Director). (1988). “Searching for Mei.” My Neighbor Totoro [Screenshot]. Studio Ghibli.

Napier, S. J. (2018). Miyazakiworld: A life in art. Yale University Press.