Introduction

Academic research is of high research interest because it is primarily aimed at improving the quality of education. Including when research involves early childhood students, it is critical to maximize the reliability of the results, as this is a susceptible area. The effectiveness of the final results depends on the reliability of the research methodology being conducted, and therefore, in the early school context, it is crucial to provide as unobstructed but constructive an environment as possible (Epstein, 2018). The principles above hold for English language learning for students with alternative socio-cultural backgrounds — or otherwise known as ELLs — but academic foreign language learning for young children involves issues such as cultural differentiation, pedagogical personalization, and adapting the curriculum to the needs of the classroom, among others.

With the profound digitalization of society, there has been an increase in the number of technological ways that students can learn a language. Professional teachers in the classroom use such online platforms to increase optimization and student engagement (Cakrawati, 2017). However, reliable, evidence-based information about the experiences of specific applications is scarce, and therefore the systematic use of such systems may pose a threat to the quality of students’ ELL education. One such system that has gained well-deserved popularity is NetEase Youdao, which has a cumulative stream of 22 million participants (GETChina Insights, 2019). Youdao from the Chinese conglomerate NetEase presents teachers with a wide range of professional options with translation based on big data and machine learning models (Yu, 2020). Over time the system has expanded and evolved considerably, and Youdao’s online dictionary is now used in schools — including early learning — to assist English language learners with translation.

The research paper is based on a profound recognition of the importance of examining the effectiveness of early childhood education methods and critically testing the reliability of the available results. The underlying purpose of this study is to examine in detail the NetEase Youdao online dictionary as a teacher’s aid to early grade ELL learners. The paper is a valuable synthesis of available academic information and is therefore relevant to the student community and qualified teachers in the relevant field.

Literary Review

The Need to Learn English

In today’s world, there is an enduring trend toward the internationalization. In the context of different socio-cultural backgrounds, this means that communities strive for close unity and integrity. For example, one of the most apparent manifestations of this cultural integration is the desire of communities to learn English as an international language, which allows individuals even from different linguo-ethnic families to freely communicate and share relevant information (Matsuda, 2017). Because English has been recognized as an international language since the late Middle Ages, the benefits of learning it early have already become apparent to all cultures, according to Pennycook (2017). Including language learning often begins as early as early school, as the need for the earliest possible mastery of the linguistic foundations is recognized.

For the purposes of this literature review, it is the need for early language learning that draws particular attention, as the study evaluates the effectiveness of an online platform for early learners. It is of severe academic interest to clarify the age at which a child should begin learning a foreign language and as a second one. In fact, there are two points of view on this issue, namely the need to learn English as early as possible and, conversely, to start only when the student is confident in their native language. Proponents of the first view see the benefit of early learning itself in the fact that building language abilities at an early age more effectively reinforces positive outcomes (Murtaza and Mahmood, 2018). This connection is justified by the more intense formation of neural connections and long-term memory storage during childhood (Linder and Sjögren, 2020). On the other hand, academics argue that learning a foreign language should not be paramount but should begin when the individual already has the basics of native speech (Kalra, 2018). The central kernel of the idea in this view is the assumption that mastery of the word constructions of the native language will help identify and find similar patterns in the second language. However, it is worth stressing right away that these hypotheses are specific to learning in childhood only (Ran and Lu, 2020). Although adults are much more confident in language acquisition, they are less capable than children of academic learning and have a lower potential for forming beneficial neural connections. Consequently, these assumptions hold for older children but not for adults.

Challenges for the Chinese student

The academic community became interested in an in-depth exploration of methodology that would achieve better school results. That is why by now, the pedagogical group has accumulated many teaching practices and methodological aids that reveal different approaches to learning English. In this context the development of programs that allow students from Asian cultures — particularly China — to develop English language skills and competencies is of particular importance. In practice, English is in demand in the local community that approximately one-third of the entire mainland population is learning the language (Zhenyu, 2020). It is to be expected that these numbers will continue to increase as cultural integration processes intensify.

As it is known, the Chinese pedagogical system is very demanding on results, and therefore it dictates a rigorous approach to language learning. The child from early childhood begins language learning with conceptual foundations and forms. In this context, it is essential to emphasize the severe language bridge that exists between Chinese and English speech (Yang et al., 2017; Zhang and Zhan, 2020). Whereas Chinese children are accustomed to using symbols and characters with unique semantic meaning, English offers a very different linguistic form, namely alphabetic writing. English-speaking students often find it difficult to understand how intonation during speech can mean changing the meaning and message of words because raising or lowering the voice on specific words in Western countries means lexical emphasis and the emotional emphasis. In contrast, in the case of Chinese, such intonation is aimed at creating an entirely new meaning for the written characters.

A Technology-Centered Approach

However, it would be a mistake to say that such a difference in the concept of two languages is not controlled by the multitude of pedagogical approaches that have been developed. Since digital technology has become ubiquitous, schools and kindergartens have also tried to integrate technology into learning (Brito and Dias, 2018). Many researchers agree that this approach has a positive effect on the educational system, as it qualitatively increases the level of involvement and provides an excellent opportunity for teachers to optimize lesson structure (Rosenfeld and Martinez-Pons, 2005; Ahmadi and Reza, 2018). At the same time, the digitalization of education helps to modernize the school, and thus, with the proper level of management, increases its attractiveness and competitiveness in the eyes of parents and students (Thomas et al., 2012). In the context of bridging the language bridge between two languages, the use of technology forms a qualitatively new approach called TELL (Zhou and Wei, 2018). This idea implies the vast potential of technological equipment and digital capabilities to improve the culture of learning and seriously improve the results. In general, TELL is an accepted practice, and many researchers have commented on its high potential for Chinese schools (Hao et al., 2021). The use of smartphones by Chinese students has increased to 78.5 percent, with one in four students younger than fourth grade typically having their own electronic device (Thomala, 2021). This poses a definite technological challenge to the teaching community, as not incorporating smartphones into instructional practices — in other words, MALL — can lead to less effective instruction (Levy and Stockwell, 2013). The subdivision of TELL aimed at cell phones is often referred to as MALL in the academic literature: it should be emphasized that there are significantly fewer reliable results on the effectiveness and optimization of learning with this process (Zou et al., 2020). Nevertheless, sources still highlight MALL as a qualitative approach to language learning, which means that a qualified teacher should look out for this practice.

Developing Assessment Systems

A still big exploratory issue of pedagogical practice attempts to systematically determine the proposed teaching methodology’s effectiveness. The problem is that often teachers in the classroom act intuitively, which means it is difficult to point to the possibility of a formalized teacher evaluation system (Tomlinson, 2013). This is a misjudgment because the intuitive approach does not imply complete permissiveness and independence of the teacher during the lesson but instead reflects the clever use of accumulated pedagogical experience and theoretical learning at the university. In the context of learning assessment systems, an intuitive approach to teaching is a highly effective teacher strategy for making subjective judgments about the effectiveness of specific proposals (Hough, 2020). Thus, the most obvious — and therefore one of the most common — methods of assessment is to try to put pedagogical technology into practice in the classroom and collect results and opinions from stakeholders (Tomlinson, 2013). To put it another way, a professional may try to introduce the practice of using a digital application for linguistic learning and, after a certain period of time, collect formative student evaluations to make final judgments about the effectiveness of such a method. However, the scholarly community suggested other valuable practices, among which it should be highlighted the teacher’s collective discussion with parents (Boonk et al., 2018). This option qualitatively improves family engagement and personalizes classroom practices to the needs of the team.

Another assessment technique that is also in high demand among teachers is the use of checklists to monitor performance step-by-step. First of all, using checklists means comparing the technique or methodology being studied to existing benchmarks, which means that if the postulates of the checklist are reliable, such an assessment system has high academic potential (Tomlinson, 2013). Second, the checklist concept is built on the principle of step-by-step comparison: it follows that the program being developed must be fragmented and studied thoroughly (Smets, 2019). Finally, using the checklist model in the classroom allows the teacher to find specific weaknesses and vulnerabilities in the pedagogical technique and address them in a way that preserves the overall idea of the methodology. Consequently, in today’s classroom, the teacher should not ignore this assessment strategy.

However, it is also important to note that assessment of instructional techniques should not be a one-time activity but rather should be systematic and systematic. It should be understood that pedagogical practice is inextricably bound up with the current agenda, so one cannot expect a teacher’s program that works today to be effective tomorrow. In fact, it is the teacher’s job not only to develop but also to continually update pedagogical assessment systems so that even in changing external environments, it demonstrates high effectiveness for the classroom. For this reason, some authors emphasize not only the retrospective function of classroom assessment but also the predictive function: This approach allows the competent teacher to manage change promptly and to address assessment problems proactively.

The Context of Chinese Learning

Ever since the recognition of English as an essential skill for international exposure to local culture stopped being questioned, the Chinese community has shown a severe interest in the issue. In fact, it is no longer a revelation to anyone that a confident command of English from an early age allows a child to have more opportunities in their senior years and to compete effectively for student and work placements in an overcrowded environment. All of this has led to the fact that by now, China has formed the most significant English language learning market in the world, and this statistic is very likely to continue its upward trend (Deloitte China, 2018). This leads to the conclusion that the modernization of early preschool learning systems is a vital need in the Chinese school setting.

One of the prominent trends in English language learning for the local community has been a clear focus on shifting parental priorities and expectations. Thus, in an attempt to maximize results in a short amount of time, Chinese parents are willing to overpay a specialist if they is a foreign English speaker, as opposed to an experienced local teacher. In the context of this study, this fact is crucial because it reflects the need for the adaptive nature of the pedagogical materials used: the teaching techniques used must be relevant in both the group classroom setting and the private nature of one-on-one lessons. For the Chinese market, such a permanent solution has been the profound use of technological tools, including mobile applications. The commitment to the TELL approach is reflected in the conceptualization of ideas for such platforms. The most popular apps on the Chinese market, like ClassDojo or Study Flash, are indispensable tools for the modern teacher in planning and structuring future lessons (Rogers, 2017). Their use facilitates progress management and presents teachers with a wide range of pedagogical options, including the use of online report cards, incentive systems, a calendar, and audio-visual cards to assist in the expansion of a student’s ELL vocabulary. Other apps, which are also actively used by Chinese users to learn English as a second language, also have their own competitive advantages. For example, FluentU provides the ability to search for specific words or word constructions in English-language movies to improve speaking skills (Rogers, 2017). Memrise makes it easier to learn new words and records student progress, replacing the teacher’s classic types of formative assessment. Finally, Kahoot! aims to implement a collaborative game format to increase the engagement of all students in the lesson (Rogers, 2017). The idea of MALL, in these cases, is supported by the functionality of allowing students to use their own mobile devices to select the correct answer in a quiz, which the teacher projects on the wall in the classroom. Thus, it can be concluded that the market for technological solutions in modern Chinese English learning is diverse and competitive.

Using NetEase Youdao

Along with the digital learning platforms discussed, there is tremendous research interest in evaluating the effectiveness of using NetEase Youdao for a class of young ELL students. According to Pandaily (2017) and Martin (2018), Youdao is used by the local community primarily as an online dictionary to improve contextual translation from Chinese to English. For this reason, Youdao stands out significantly from “classic” apps like Google Translator — which is all the more blocked in China — or Pleco Chinese Dictionary, as it allows for the improvement of full-text translation practices rather than word-for-word (Martin, 2017). Consequently, Youdao can be incorporated into everyday elementary school practice in a way that expands ELL students’ vocabulary and encourages learning idioms and full-length constructions for greater confidence in foreign speech. In the following sections, the practicality of using NetEase’s Youdao online dictionary in an elementary classroom setting is explored in detail and comprehensively. More specifically, the use of existing assessment practices is discussed to adapt and modernize them to fit a given research framework.

Context

It is paramount to recognize that China is a highly harsh communist country whose rules are dictated not only by the ideology of the current government but also by the phenomenon of overpopulation. For thirty-six years — from 1980 to 2016 — the Chinese authorities imposed a reproductive ban to support the state’s demographic policy (Zhang, 2017). In particular, urban dwellers were forbidden to have more than one child, and therefore today’s schoolchildren often do not have siblings. Compared to the Western student, the Chinese student is under much harsher and more stressful conditions. Local students are forced to give up their leisure time to do much homework, study with tutors after school, and begin each morning with the national anthem (Wu, 2017). However, this rigidity is not accidental: the parents of children are determined to give their child a better future, and therefore in the face of severe overpopulation, they are willing to sacrifice their child’s childhood for better results and competitive advantages.

The harsh life of Chinese schoolchildren, however, is rapidly adapting to the realities of modern morality. Until recently, mild corporal punishment, public humiliation, and punishment through physical exercise were allowed in Chinese elementary schools, but these are now banned (Wion, 2021). Instead of such harsh punishment procedures, the modern Chinese schoolchild who has been guilty of something is forced to write extended homework or complete additional assignments. Although the level of harshness in Chinese schools has declined, it is still very high, and therefore local students are under systematic stress. This is extremely important for the ESL teacher to consider when planning a lesson.

In standard practice, Chinese children begin learning English as a second language in the third or fourth grade, depending on the school curriculum. However, if parents were interested, the child could begin learning the language with a tutor at an early age so that by elementary school, the student would already be proficient in English grammar and vocabulary. In other words, children in the same grade can have completely different language proficiency levels, which is also something the ESL specialist should consider. In addition, since this study measures the effectiveness of using the MALL approach for linguistic learning, it is essential to consider the culture of Chinese schools’ attitudes toward technology. The Ministry of Education explicitly prohibits cell phone use (and even carrying) of cell phones by students in school (Wakefield, 2021). This prohibition is due to concerns about preserving vision and strict lesson discipline. That said, a child may still have a phone with them if the parent has written consent to do so in advance.

All of the above should be considered when planning a lesson for ELL students in Chinese schools. Along with restrictions on mobile technology, serious adult and social pressures, and much work, an essential factor in the Chinese school is the large class size. For example, the average British class includes 20.4 students, while the average Chinese class reaches the fifty-child mark (Rhodes, 2017; Schoenmakers, 2017). Consequently, lesson implementation practices in Britain and China differ significantly in approach, and therefore additional methodological work on strategic planning is required for ESL teachers before performing a lesson.

Evaluation

Choice of the Evaluation Tool

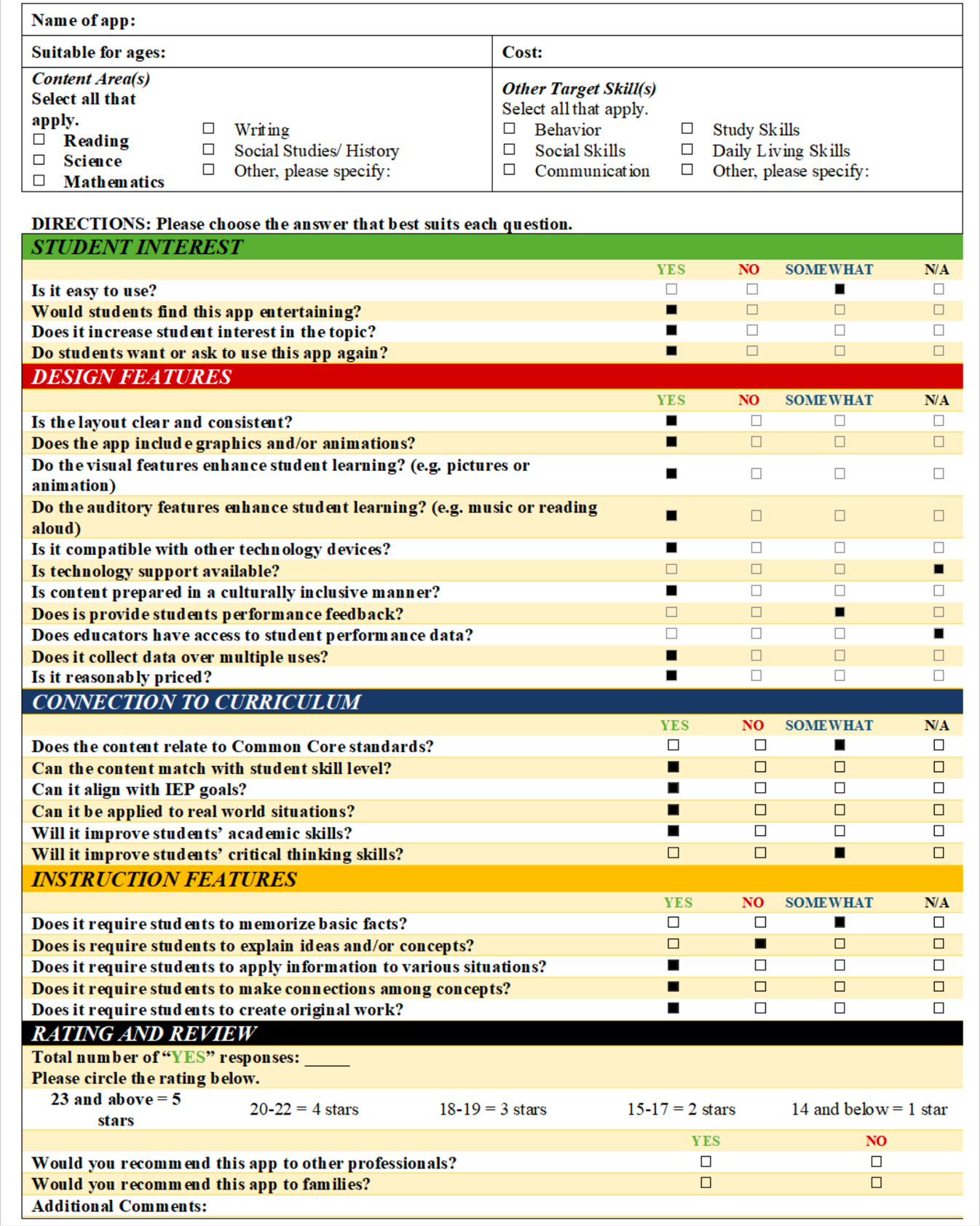

To evaluate the effectiveness of a digital tool in the context of this study, a checklist strategy was chosen to provide a step-by-step control of operational performance. As previously mentioned, the checklist model has serious advantages over other evaluation systems, and therefore its use in this study is supported. Nevertheless, of great importance is the choice of such a system, characterized by high reliability and quality of the control carried out. In other words, it is necessary to eliminate the situation where a tool that does not meet academic levels of correctness and standards is used as a checklist. This is not such an easy task since often such checklists are made either by single teachers or by people who have nothing to do with academic language learning in elementary schools. As a result, such checklists may not reflect the full breadth of pedagogical assessment, instead emphasizing only those performance factors that seem to prioritize the individual. Consequently, choosing a checklist is the best strategy to research the scholarly literature that has raised similar questions. For this purpose, the study of Lubniewskia et al. (2018) aimed to determine the effectiveness of teachers’ use of digital apps for academic purposes. This is a similar study, and printing in the highly ranked journal IEJEE makes the checklist from the article reliable.

A Brief Description of the Checklist

So, once a particular type of checklist has been selected for use, descriptive work needs to be done before proceeding with the critical appraisal. This will provide a deeper understanding of the checklist structure and allow us to discover strengths and weaknesses. Thus, the entire tool is a single A4 sheet, conventionally divided into six sectors, differentiating between different aspects of digital application use. The first section provides descriptive elements of the application, namely its name, target audience, disciplines covered, and skills to develop. It is interesting to note that it is appropriate to select more than one response option in this section if it fits the situation.

In contrast, the following sections offer the teacher or instructor only one response option to choose from, which might best describe the state of the digital application for use. Specifically, the second section of the checklist asks the educator to think about student interests when implementing this tool in the classroom. The key questions here relate to ease of use and the ability to get a child interested in using the app. Notably, the section on student interests is the opening section. This supports the idea that modern education is focused primarily on the student’s needs rather than following previously invented tenets and principles (GES, 2017). To put it another way, when developing new curricula or tools to be used in the classroom, the teacher should think first and foremost about children’s interests, because if children do not show engagement in the educational process, such technology proves not only highly ineffective but also harmful. It is also noteworthy that the teacher has four options for evaluation: “yes,” “no,” “somewhat,” and “no response.” This makes it easier to grade digitally since not all questions can always be answered unambiguously. Once the “student” portion of the checklist has been completed, the teacher can complete the digital application design section.

Thus, the third section of the checklist focuses on conducting a critical assessment of the functionality and accessibility of the app. This includes eleven questions with the same four answer options: these options persist until the sixth section (not included), which summarizes the results. The eleven questions in the third section consistently assess the differentiated content in the app, the integration possibilities with other electronic devices, and the justifiability of the price.

It is difficult to call any one section of the checklist central, as each evaluates different aspects of the application’s use differently. Thus, when each of them is analyzed together, it becomes possible to build an overall picture of the digital tool. Therefore, the fourth section links the technology used and the work standards that govern the classroom. This includes just six questions that ask very explicitly about the educational use of such an application. It is interesting to note that the first question of the section assesses the consistency of the proposed functionality with the Common Core set of academic standards. It should be emphasized that the teacher community’s attitudes toward these standards are generally ambiguous. Some elementary teachers actively use these regulations in their work because they best cover all necessary topics and age-appropriate learning needs in school subjects (Meador, 2019). In contrast, some teacher groups speak negatively about the use of Common Core, hinting at the inability of the regulations to adapt to students of different levels (Armstrong, 2018). In reality, elementary school classrooms are rarely formed to have the same levels of proficiency in English or other subjects. On the contrary, more often than not, some students are gifted compared to others who appear less successful against them. Thus, using a single standard may not support the differentiation of competencies in the classroom, which can lead to serious interpersonal problems and conflicts within the student body. This is why many teachers with experience using these standards have tried to abandon them in favor of other regulations. Finally, it should be said that although Common Core has received widespread adoption around the world, it was initially aimed at the USA. As such, it seems inappropriate to use the same materials for native speakers and ELL students. Consequently, qualitative changes are proposed for this checklist, which will be discussed in detail in later subsections. The following five questions form the fifth section of the checklist, which focuses on the institutional specifics of application use. More specifically, the fundamental interests here are to establish the need to explore new facts and concepts. In other words, the fifth section focuses on determining the level of academic burden that is imposed on elementary school students.

Using critical assessment in completing twenty-six questions, the educator approaches the last section, summarizing the entire checklist. Specifically, the only measure of effectiveness on the checklist is the number of “Yes” responses throughout the measure. So, depending on this number, the app can be given a rating illustrating its reliability and effectiveness for early childhood learning. That said, the checklist does not offer a final grade for the teacher but instead allows the professional to decide whether to use the digital tool in future practice. Notable are the last two questions on the checklist, which ask the teacher whether they would offer the app to other professionals and families alike. The closing questions can be critical to the measurement for several reasons at once. First, they represent a reflective analysis: even if the app is classified as highly effective based on the number of “yes” responses, negative responses to the closing questions may change the professional’s attitude toward digital technology under the measurement. Second, asking about the opportunity to share tools with colleagues raises the teacher’s responsibility to the teaching community. If the professional firmly believes in the app’s effectiveness, they can recommend it to colleagues. Alternatively, if the app does not seem reliable, the teacher is unlikely to take on the responsibility of sharing it with others. Thus, this question reveals the problem of professional responsibility and thus provides a more profound impression of digital technology. Finally, the last question of the section focuses on the possibility of sharing this tool with families. It seems evident that the central theme in this question is the involvement of families in the educational process. It is known that the effects of such integration on children’s learning are most favorable (Boonk et al., 2018). Consequently, the teacher should encourage children’s involvement in school, and the final question of this measurement tool seeks to support these very thoughts.

Ultimately, the six sections discussed form a coherent and unified measurement methodology that critically evaluates the effectiveness of digital technology. As can be understood from the previous paragraphs, the proposed checklist provides a comprehensive assessment, and thus it is appropriate to use it as part of this study. The following subsections discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the online dictionary successively understudy and provide recommendations for improving both the checklist and the technology to cover more academic needs.

The Functionality

The best strategy for measuring the effectiveness of the selected study material, namely the NetEase Youdao application, is to follow a series of sequential questions given in the selected checklist. Such a solution will not only allow the conclusions about the effectiveness of the selected program for Chinese ELL early learners to be drawn but will also allow the entire application to be fragmented in order to determine its weaknesses and strengths. Before proceeding with the critical evaluation, however, it is necessary to describe the functionality of the online platform in detail. According to the developers, NetEase Youdao is one of the most practical and efficient online tools to translate individual words, phrases, and whole texts in real-time. The quality of this translation is justified not only by the inclusion in the software base of a list of the most authoritative dictionaries worldwide but also by the focus on machine learning. The quality of translation is improved automatically by improving the quality of translation algorithms. However, with NetEase Youdao, the user also gets simultaneous translation via camera, reference records for interpreting unknown words, and the ability to translate even offline without a network connection.

In addition, the app’s features also include game-based educational content that allows not only to learn new words but also to practice them. More specifically, the app has a built-in Discovery Channel section that gives the student free access to various educational content, and Youdao Classroom opens up opportunities to participate in online courses to improve language or prepare for exams. Some of the user interface elements are shown in Figure 1. Notably, the full range of functionality is available to users not only on a cell phone but also on a computer: the downloadable program can be found in the AppStore or Google Play, as well as on Chinese search platforms.

Strengths and Weaknesses

According to the checklist, the first section should include descriptive information. For NetEase Youdao, the age range is not limited, but this study plans to use the software for elementary school students in China; therefore, the audience’s age range is 6 to 10 years old. The app covers the need for educational content aimed at learning reading, writing, and grammar. Part of the educational content covers social issues, so it is appropriate to note the broad focus of NetEase Youdao: this is a strength. Combined with essential linguistic competencies, using the app covers competencies in writing, communication, and conversational skills if the student plans to use English in the future.

A discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of using the current version of the app in the instructional setting is further performed according to the completed checklist (Figure 2). So, the app has the design (Figure 1) of a regular multifunctional app, which means that in general, it is not difficult to figure out which sections are available for use. However, the app seems to weigh too much and is poorly optimized for weak devices, so many users complain about long content loading times.

Therefore, NetEase Youdao cannot be unequivocally characterized as easy to use. However, multifunctionality is at the same time a competitive advantage of the application. During ESL lessons, the teacher can offer the children several activities — both collective and individual — involving using a digital tool at once. Examples of such activities include a game of the fastest and best English text translation, collaborative reading of English literature with vocabulary study of unknown words, and lessons devoted to correcting specially made errors in text fragments using contextual translator tools. Finally, a severe vector in ELL students’ learning can be an independent exploration of idioms and established phrases in English with a search for Chinese counterparts. With all this in mind, the answers to questions 2, 3, and 4 of the first section are unequivocally positive. The total number of “yes” answers in this section was 3 out of 4.

The design features of NetEase Youdao are also subject to critical evaluation using the checklist. For example, the application’s user-friendly menu and clear structure, as well as the ability to change the language of the entire system to preferred language, make its structure clear and user-friendly. In addition, the application makes extensive use of audio-visual material to simplify the understanding of the theoretical foundations. In this context, it is worth highlighting the real-time translation functionality (Figure 3), which simultaneously covers the need to use pictures and enhance students’ academic competence. At the same time, the application allows exploring the pronunciations of the words being studied, which covers the need to use different communication channels. In addition, NetEase Youdao offers the student self-study online courses that use both visual and audio accompaniment to reinforce better word memorization effects. Finally, the free nature of the application and the possibility of multiple uses with retention of progress also form the sum of the severe advantages of NetEase Youdao.

However, a study of the capabilities of the application did not yield any results about the available technological support in case of problems. In particular, the proposed translation, although highly accurate, can be erroneous: in such a case, an experienced professional can try to suggest changes. In NetEase Youdao, no feedback options were found about the app’s learning features, but there is a button to contact support regarding technical problems of use. For this reason, this line was not answered affirmatively or negatively. The app’s ability to give feedback on student progress is also unknown. In fact, a child can show the teacher pages of personal progress, but it is not entirely clear how NetEase Youdao can be used to create summative assessments. Overall, in the third section of the checklist, the app has both strengths and weaknesses: the total number of “yes” responses was 8 out of 11.

The connection to academic standards is of profound importance to the application because even a great design and a wide range of features can be useless if NetEase Youdao does not comply with the basic regulations in teaching. Since Chinese schools, in general, use a variety of approaches, it is not easy to choose only one local standard for learning English as a second language. Instead, it is acceptable to use the general standards designed for the international contingent listed by ERIC (2000). A consistent comparison of the functionality of NetEase Youdao and the common academic standards makes it clear that the app generally conforms to these principles and supports the need for the academic acquisition of new knowledge. At the same time, the app is inextricably linked to the real world not only through the development of the extremely important language competencies of the modern, confident individual but also through the use of the camera translation feature. The total number of affirmative answers in the fourth block of the checklist was 4 out of 6.

Finally, the last section of the measurement tool is the NetEase Youdao institutional features survey. In fact, the program requires the student to memorize the principles of the application, but this cannot be called a weakness because it is inherent in any software. That said, the actual use does not require the elementary school student to explain any ideas or concepts, although the teacher can modify this. For example, an ESL specialist might ask ELLs to find meanings for some English words. That said, the strengths of NetEase Youdao are the proximity of the concepts being taught to current agendas and real-life events, including through the translation of actual texts. In addition, using the app requires students’ critical thinking competencies: the teacher can offer students a knowingly incorrect translation so that students find the mistakes on their own. Finally, an ELL student can use the app to produce original work. The most straightforward scenarios for such use might include a personal translation of a given text or finding synonymous meanings for a term. Thus, the penultimate section of the assessment tool collected 3 out of 5 positive responses.

To review all the evaluations, the total number of positive responses for NetEase Youdao should be summarized. This number was eighteen, which means that this software should be categorized as “three stars.” Interpreting this result, NetEase Youdao can generally be used for Chinese elementary schools in learning English as a second language, but some changes need to be made.

Suggested Improvements

As shown, NetEase Youdao needs several changes to match the school’s academic expectations more closely. First and foremost, the application should add an academic support feature so that an experienced professional can correct inaccurate translations. In addition, support can also be provided for students if a child makes many mistakes during individual course assignments. In this case, online assistants can offer the student paid help, but this approach would make the application only conditionally free. Second, the changes could be about setting up teacher-student feedback opportunities. Specifically, NetEase Youdao could invite teachers to create private classes that reflect the progress of all students in the group. In turn, the teacher could send the children recommendations for assignments and answer their questions. Finally, the development of nationwide Chinese standards in learning English as a second language is needed. It is known that a similar project was initiated back in 2014, but it proved to be irrelevant and was soon closed (Jin et al., 2017). Thus, the development of academic ESL standards will shape the framework in which NetEase Youdao will have to implement activities and add functionality. Thus, the proposed three improvements should be sufficient to improve the reliability and efficiency of NetEase Youdao qualitatively. In addition, developers should constantly monitor the status of mobile and desktop applications and ensure optimization even on older devices.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it should be emphasized the need for continuous and systematic critical evaluation of new tools that are used in the education of elementary school students. With the widespread use of digital technology, the number of such learning platforms has increased significantly, but not all of them meet the general academic requirements and therefore cannot bring positive learning outcomes. In this study, the famous Chinese software NetEase Youdao, which has both mobile and desktop versions, was chosen as such an application. A checklist strategy was used to evaluate this software, which was isolated from the academic literature. Thus, the checklist has increased reliability and scientific validity.

The results of the critical evaluation showed that the NetEase Youdao program has an average performance on younger students. In fact, NetEase Youdao has a large number of strengths, which translate into developed functionality and generally meeting the academic expectations of the classroom. Nevertheless, weaknesses have also been found to hinder the effective operation of the application. Consequently, qualitative improvements need to be made for a better user experience. The paper suggested at least four such improvements, including the addition of functional features and the development of nationwide Chinese standards for ELL learners. All of these together would comparably improve the application and thus create a more supportive and constructive classroom culture in elementary schools. As a result, the appropriate use of digital technology in school is recognized as highly effective if the teacher is proficient in it and adapts it to the learning objectives and the cultural background of the classroom.

References

Ahmadi, D. and Reza, M. (2018) ‘The use of technology in English language learning: a literature review,’ International Journal of Research in English Education, 3(2), pp. 115-125.

approach in English language lessons for early age groups,’ Journal of Early Childhood Care and Education, 2, 1-19.

Armstrong, T. (2018) 12 reasons the Common Core is bad for America’s schools. Web.

Boonk, L., Gijselaers, H.J., Ritzen, H. and Brand-Gruwel, S. (2018) A review of the relationship between parental involvement indicators and academic achievement. Educational Research Review, 24, pp. 10-30.

Brito, R. and Dias, P. (2018) ‘Digital technologies in kindergarten: Paths of kindergarten teachers and potentialities for children,’ Learning Strategies and Constructionism in Modern Education Settings, 1(1), pp. 114-130

Cakrawati, L.M. (2017) ‘Students’ perceptions on the use of online learning platforms in EFL classroom,’ ELT Tech: Journal of English Language Teaching and Technology, 1(1), pp. 22-30.

Deloitte China (2018) A new era of education. Web.

Epstein, J.L. (2018) ‘School, family, and community partnerships in teachers’ professional work,’ Journal of Education for Teaching, 44(3), pp. 397-406.

ERIC (2000) The ESL standards: bridging the academic gap for English Language Learners. Web.

GES (2017) Education is primarily about helping young people get jobs – yes or no? Web.

GETChina Insights (2019) NetEase Youdao goes all in on K12 education sector after the restructuring. Web.

Hao, J., Guo, J. and Wang, C.X. (2021) ‘Innovation and reform on technology empowered education: the 24th global Chinese conference on computers in education,’ TechTrends, 65(1), pp. 2-4.

Hough, L. (2020) A teacher’s intuition. Web.

Jin, Y., Wu, Z., Alderson, C. and Song, W. (2017) ‘Developing the China Standards of English: challenges at macropolitical and micropolitical levels,’ Language Testing in Asia, 7(1), pp. 1-19.

Kalra, S. (2018) Know how not learning English at an early age can have its own benefits. Web.

language in the early school years,’ Malmo University, 1-15.

Levy, M. and Stockwell, G. (2013) CALL dimensions: Options and issues in computer-assisted language learning. London: Routledge.

Martin, T. (2018) Mobile apps in China — which should you use? Web.

Matsuda, A. (2017) Preparing teachers to teach English as an international language. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Meador, D. (2019) What are some pros and cons of the Common Core state standards? Web.

Murtaza, T. and Mahmood, M. (2018) ‘Active learning through project based learning

Pandaily (2017) NetEase Youdao aims to make traditional translation market more internet-oriented. Web.

Pennycook, A. (2017) The cultural politics of English as an international language. London: Taylor & Francis.

Ran, S. and Lu, Y. (2020) ‘Supporting children to learn English in Chinese kindergarten,’ Journal of Contemporary Educational Research, 4(4).

Rhodes, D. (2017) Number of children taught in large classes trebles. Web.

Rogers, M. (2017) 10 English teaching apps for the 21st-century ESL teacher. Web.

Rosenfeld, B. and Martinez-Pons, M. (2005) ‘Promoting classroom technology use,’ Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 6(2), pp. 145-153.

Schoenmakers, K. (2017) China’s most crowded school has 113 children per classroom. Web.

Smets, W. (2019) ‘Challenges and checklists: Implementing differentiation,’ Agora, 54(2), pp. 22-26.

Thomala, L. L. (2021) Usage of electronic devices and mobile phones among students in China 2018-2019. Web.

Thomas, M., Reinders, H. and Warschauer, M. (2012) Contemporary computer-assisted language learning. London: A&C Black.

Tomlinson, B. (2013) Developing materials for language teaching (2nd ed.). London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Wakefield, J. (2021) China bans children from using mobile phones at school. Web.

Wion (2021) China bans school punishments that could cause mental and physical trauma to students. Web.

Wu, D. D. (2017) Be respectful to China’s national anthem! Or you might face detention. Web.

Yang, M., Cooc, N. and Sheng, L. (2017) ‘An investigation of cross-linguistic transfer between Chinese and English: a meta-analysis,’ Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 2(1), pp. 1-21.

Yu, C. (2020) NetEase Youdao launches online course platform. Web.

Zhang, F. and Zhan, J. (2020) ‘Understanding voice in Chinese students’ English writing,’ Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 45, pp. 1-8.

Zhang, J. (2017) ‘The evolution of China’s one-child policy and its effects on family outcomes,’ Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(1), pp. 141-60.

Zhenyu, L. (2020) English education in China: An evolutionary perspective. Web.

Zhou, Y. and Wei, M. (2018) ‘Strategies in technology-enhanced language learning,‘ Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 8(2), pp. 471-495.

Zou, B., Yan, X. and Li, H. (2020) ‘Students’ perspectives on using online sources and apps for EFL learning in the mobile-assisted language learning context,’ Language Learning and Literacy: Breakthroughs in Research and Practice, 1(1), pp. 515-531.