Introduction

Product positioning refers to the marketers’ abilities to arrange or distribute a range of products or services in a manner that arouses interest of consumers in a company at the expense of its competitors. When Nissan transferred its operations from South Korea to Japan, it also made major changes, including the appointment of a new CEO, Carlos Ghosn.

In reference to Nissan’s recent performance in the automobile industry, the company seems to enjoy much consumer attention because of the electric cars, fuel saving engines, and high-tech designs among other features. According to the paper, Nissan underwent a radical change in terms of production, design, and leadership, a process that is very difficult to undergo (Simchi-Levi & Schmidt, 2012).

Though the company’s headquarter is in Yokohama, Japan, it manufacturers most of its latest cars like Nissan Bluebird in South Korea. The alliance is not new since Nissan has enjoyed partnership with Renault in South Korea from 1999. Common Nissan brands include Infiniti, NISMO, and Datsun manufactured in Japan and South Korea concurrently under the leadership of Ghosn.

The intention of the paper is to explain how change had a positive impact on Nissan’s ranking in the world since 2013. Recently, the company enjoyed sixth position behind major vehicle manufacturers in the world such as Toyota, Ford, and Volkswagen.

History

Nissan is a multinational company that uses the selling philosophy of marketing orientation in capturing the attention of the growing consumer base. The company acquired prominence in the 1930s even though the Datsun brand existed since 1914. Under the name Kwaishinsha Motor Car Works 103 years ago, Nissan had the DAT as the first innovation.

After 7 years of operation, the company changed its name to DAT Jidosha and Company Limited for purposes of branding and easy identification with the company’s products. In the same year, the company transformed from a manufacturer of the renowned Nissan Model 70 Phaeton (1938 model) to Datsun vehicles that could carry passengers (Nissan Motor Company Global Website, 2014).

The change attracted commercial car owners who also required heavy-duty trucks for production, and military cars fitted with defense facilities. Among countries that imported the Nissan cars, the US preferred the Japanese manufactured vehicles to trucks from other companies. After a merger with Jitsuyo Jidosha Company in Osaka, Japan, Nissan rebranded to DAT Jidosha Seizo Company Limited Automobile Manufacturing Company Limited.

By the 1920s, the strategy was to reduce the physical size of Nissan cars while increasing their capabilities. The company came up with Datson to indicate a small version of the original DAT. A decade later, the company became Nissan Motor Company; it has retained the name to date.

However, the company underwent a series of changes in leadership as indicated by the presence of 13 Japanese CEOs from 1933 to 2001. Today the company has a Pilipino CEO who records an immense history of success in the company.

Change

Change refers to a visible event that leads to the recognition of an organization in a positive or a negative manner. Normally, organizations measure change by assessing the duration taken and effort made towards the achievement of the change. Nissan’s change concept included a focus on its leadership structure, the models, organizational culture, and marketing (Nissan Announces Management Change in the Philippines, 2014).

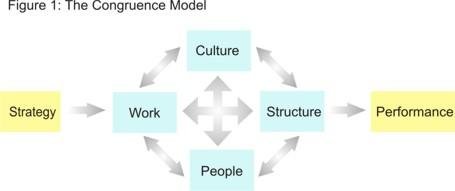

The congruence model of change concerns identification of a problem and seeking of long-term solutions in an interconnected manner. David Nadler and Michael Tushman came up with the congruence model that explains that organizational success is an outcome of people, culture, task, and structure. Nissan had to transform its organizational culture as illustrated in the following illustration.

(Nilakant & Ramnarayan, 2006)

Nissan took a demographic outlook of its business procedures in 2001, and it considered employing a foreign CEO who would run both the South Korean and Japanese Nissan firms concurrently. Arguably, the process would save costs for the firm while ensuring that Nissan had a team and not a group of employees by the time it underwent a complete overhaul (Nilakant & Ramnarayan, 2006).

Since the people cannot change an organization without a transformational structure and culture, Nissan had to incorporate a culture of inclusivity in 2013. Through the culture, it incorporates the ideas of other team members willing to draw different automobile designs from trucks to luxury vehicles and passenger vehicles.

Structurally, Nissan is a mechanistic organization whose operations aim at improving previous innovations in order to meet the growing automobile demands. Driving forces towards the change included the ability to create a demand that would meet the aesthetic needs of the diverse consumers.

Culture of the organization

The original culture of the organization under Yoshisuke Aikawa for six years since 1993 displayed a dictatorial approach to issues. Prominent leaders including Takashi Ishihara, Souji Yamamoto, Takeshi Murayama, and Taichi Minoura among other company leaders used dictatorial approaches to govern Nissan since its inception.

To date, the influence of the first company CEO is obvious since most charity organizations and sports sponsorship programs seem to take an interest in the East instead of other parts of the world. Aikawa mostly incorporated the American culture in which the company had to improve its innovations after particular period.

Nissan supplied the Graham-Paige Company in the US, and its designs had to match the set threshold for machinery used in the US between 1985 and 1992, Nissan underwent a major leadership change under Yutaka Kume who emphasized on a strict laissez faire structure of governance (Brown, 2007). Content-driven change is a model that explains how organizations use particular programs to maintain excellent customer relationships.

Kume provided a laissez faire environment through which consumers could relate freely with the marketers and customer care departments. Even though people operated within a non-controlled environment, they had to account for their performances through a scorecard (Nilakant & Ramnarayan, 2006).

Customer relation is not a new concept at Nissan, which started to market its Datsun 16 in 1937. About the same period, the company opened a showroom in Austin even though its British branch spearheaded the marketing procedure. The 1950s saw Nissan introduce patents to protect its inventions ahead of competition from prominent firms such as Toyota and Volkswagen.

Through investor and customer relations, Nissan came up with the Nissan L engine resembling the OHC (cylinder overhead cam) of the Mercedes Benz. The invention meant that the customers wanted an advanced machinery from an automobile that served them for a long period since 1914 (Nilakant & Ramnarayan, 2006). Later, the Sedan, Tina, and the sports Datsun range of vehicles surfaced in an attempt to respond to consumers’ requests.

Carlos Ghosn’s reign followed the leadership of Yoshikazu Hanawa equally characterized by a laissez faire structure and culture. The current culture is very robust, and Ghosn’s democratic leadership style enables Nissan to enjoy the requisite competitive advantage (Adair, 2006).

The Change effort itself

When William Bridges came up with transition change model, he developed three major change stages that companies or individuals can embrace. The conduits represent the support mechanisms that help organizations to make a transition from one stage to another. Ending, losing, and letting go is the first stage that Bridges adopted; he mentioned that it is very difficult to forget initial practices prior to embracing new ways of doing things (Specto, 2010).

Some companies undergo a state of fear, denial, frustration, and uncertainty among other drawbacks that prevent change. Empathy and open communication channels form the basis of embracing change in a state of confusion. The neutral zone represents the second phase in which all people within the organization undergo confusion for inability to comprehend the best step of action to take in order to deal with the transformation (Edwards, 2000).

The stage characterized by high levels of confusion and impatience creates an environment of resentment from austere policies. Taichi Minoura and Yoshisuke Aikawa were examples of pioneers of Nissan that mostly supported their personal designs and market destinations for Nissan vehicles. In the end, the two targeted the wrong markets with the right products, which created a marketing dilemma.

Resentment towards change in the 1950s became obvious as the CEOs strived to concentrate on Russian, Chinese, and African markets, instead of the Austin market in Texas. For a long period, Nissan found comfort in North America while forgetting the significance of other emerging markets in transforming Nisan. It was until recently that Ghosn took a bold step in expanding to parts of Africa and Europe in order to premier its new collection of luxury cars, trucks, and sports vehicles (Nilakant & Ramnarayan, 2006).

The new beginning incorporates many channels of feedback because it represents a stage in which people accept change. Since it is the last transition, people have to come up with strategies that appear unique from the competitors in order to create the least possible leeway for the competitor to gain an advantage. Yoshikazu Hanawa’s transition to Ghosn was an excellent growth opportunity for Nissan.

Contrary to the common Japanese makes, Ghosn opted for both South Korean and Japanese designs (Brown, 2007). The negative impact of the change is that Ghosn does the work of executives in two rival companies. Such workloads often overwhelm CEOs, especially when they have a record of great performance.

South Korean-Renault and the Nissan Motor Company need proper management, and assuming that a single executive can achieve the objective might not be right. Changes in the 1960s signified by the sequential change model were equally obvious (Specto, 2010). Its first stage discusses the prevailing strategy, which includes the roles and relationships of the incumbent leaders.

Secondly, it deals with the training and mentoring projects as signified by the patent units introduced within Japan. The third step includes talent management that mostly involves recruitment and promotion of respective individuals in preparation for different job vacancies. Finally, the sequential model deals with the structures and systems of organizations. It includes the ability to motivate employees and ensuring that they perform excellently within a competitive environment (Chan & Drasgow, 2001).

Kume and Ghosn extensively used communication to promote cultural integration within the Nissan Company. They supported previous mergers such as Nissan and Prince Motor Company, Nissan and Fairlady, and Nissan and Dongfeng Motor Corporation among others. Under Yutaka Katayama, Nissan Sedans were exceptional, and Datsun Fairlady expanded to the US and other parts of the world.

Leadership of the change effort

Change does not come easily as explained by Kotter’s model. According to the theory, the ability to create urgency that change is necessary remains very significant for transformation. The state of urgency as supported by a SWOT analysis was obvious in the way Nissan participated in many mergers. With Infiniti, the company came up with luxurious vehicles.

The same happened with the merger between Nissan and Fairlady. Datsun and the Z-car were very important innovations that linked Fairlady with Nissan, especially during the manufacture of sports utility vehicles. Formation of powerful coalition is a second stage for the change model. Arguably, people need support since growing alone strains a company brand wise and economically.

A third element of the model that helped Nissan realize itself in the rivaled market during the era of Ghosn was creation of a common vision for purposes of change (Pinder, 2008). Common values and an all-inclusive strategy incorporated with vision and mission statements bridge the communication gap between clients, investors, employees, and supervisors.

At Nissan, a clear channel of communication might not be inexistence, but the chain of command is obvious. The CEO receives information from other managers in charge of marketing, PR, finance, and logistics among other areas of concern. Like Steve Jobs, Ghosn is at the center of most business operations while constantly intervening in case of any problems in diverse departments within the company. Removal of obstacles, creation of achievable and realistic goals, and building a positive attitude of change within the organization are the key priorities for Ghosn in creating change.

Recommendations

As at 2013, Nissan Titan was the most popular Nissan vehicle in the history of the brand. The corporation’s logo changed in 2013 marking an era of rebranding for the company amidst the battle to become the best car manufacturer in the world ahead of Toyota. Datsun, Infiniti, NISMO, and other brands also show high optimism or increased sales in the next half a decade of operation in South Korea and Japan.

According to the CSR Steering committee, Nissan’s electric cars attract Russia, Mexico, and other parts of the world than other gasoline driven cars from the company (Nissan Motor Company Global Website, 2014). Following a joint venture with Renault–Nissan Alliance in 2012, the company came up with good models such as Nissan Bluebird, Primera, and Naeta among other luxury vehicles that people can use for motorcades.

The Kurt Lewin’s change model insinuates that change is a three-step process. The unfreezing stage is the most difficult as people have to adjust to a completely new system, and uncertainty is very high. According to Grojean, Resick, Dickson, and Smith (2004), the change process remains very difficult, but through motivation people learns to embrace change until they reach the state of comfort, which experts refer to as freezing. Notably, the current CEO strives at convincing the consumers that Nissan does not only focus on good bodies for the cars, but on quality engines.

References

Adair, J. E. (2006). Leadership and motivation: The fifty-fifty rule and the eight key principles of motivating others. London: Kogan Page.

Brown, M. G. (2007). Beyond the balanced scorecard: Improving business intelligence with analytics. New York: Productivity Press.

Chan, K., & Drasgow, F. (2001). Toward a theory of individual differences and leadership: Understanding the motivation to lead. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 481-498.

Edwards, T. (2000). Innovation and Organizational Change: Developments Towards an Interactive Process Perspective. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 12(4), 445-464.

Grojean, M. W., Resick, C. J., Dickson, M. W., & Smith, D. B. (2004). Leaders, Values, and Organizational Climate: Examining Leadership Strategies for Establishing an Organizational Climate Regarding Ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 55(3), 223-241.

Nilakant, V., & Ramnarayan, S. (2006). Change management: Altering mindsets in a global context. New Delhi: Response Books.

Nissan Announces Management Change in the Philippines. (2014, July 25). Web.

Nissan Motor Company Global Website. (2014). Web.

Pinder, C. C. (2008). Work motivation in organizational behavior. New York: Psychology Press.

Simchi-Levi, S., & Schmidt, W. (2012). Nissan Motor Company Ltd.: Building Operational Resiliency. Web.

Specto, B. (2010). Implementing Organizational Change: Theory into Practice (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.