Introduction

Overview

Healthcare professionals in nearly all civilizations around the world often experience a myriad of challenges as they engage in the provision of care to patients. A couple of years ago, compassion fatigue made it to the list of challenges facing the professionals after strange behavioural orientations and attitude lapses were noticed in a group of mental health professionals headed by Herbert Freudenberger, a German psychologist (Ruysschaert, 2009).

The workers, according to the psychologist, became apathetic, distant, disoriented, and increasingly disillusioned after interacting with mental patients for a period of one year. Later, the condition was witnessed among other professionals in different fields, occasioning psychologists, researchers, and other theorists to undertake seminal studies on the concept to widen their understanding on its dynamics and impacts (Figley, 1995; Keltner & Ekman, 1996). Presently, the area continues to receive considerable interest especially in the health sector mainly due to its negative ramifications on health professionals.

In the medical context, compassion fatigue arises when healthcare professionals start to experience feelings of pain, suffering, and anguish of the patients for whom they care (Compassion Fatigue, n.d.). Figley (1995) asserts that compassion fatigue is the cost that caregivers have to pay for extending their care since the professionals end up nursing the feelings of fear, pain, and suffering after listening to their patients narrate spine-chilling accounts of what they are going through in sickness.

Once this stage is reached, the caregivers gravitate towards a situation of partial or total loss of sense of self to the patients they assist, offering more compassion than they obtain in the hope of validating their work. Ruysschaert (2009) posits that “caregivers and healthcare workers are more at risk of burnout as they face human suffering and absorb this other people’s pain” (p. 160). The variance between the caregivers and the job environment causes the professionals to become embroiled in perpetual ‘burnout, triggering feelings of entrenched physical, emotional, psychological, and spiritual fatigue. The interpersonal relationships and world views of the caregivers are also affected (Kraus, 2005).

Health professionals the world over listen to recollections of horrendous experiences, some with frightening graphic details, as illustrated by patients on a daily basis. Through the practice of empathic engagement with the patients, caregivers share the patients’ emotional and psychological burden to the issues affecting them, not mentioning the fact that the health professionals serves as witnesses to these traumatic experiences (Kraus, 2005). This burden influences the caregivers’ faculties of thought, perception, and attitude in major ways depending on the area of speciality (Craig & Sprang, 2010).

Sex offender therapists, for instance are more likely to develop “…symptoms such as hyper vigilance, suspiciousness, and increased concern for the safety of loved ones as a consequence of their work” (Kraus, 2005, p. 81). In equal measure, health professionals dealing with hospice patients may suddenly develop feelings of remorse and hopelessness due to a perceived failure to contribute to the wellbeing of the fatally ill patients (Negash & Sahin, 2009). The variations notwithstanding, it is clearly evident that compassion fatigue is a healthcare challenge that needs immediate redress to cushion the healthcare personnel from the harmful effects occasioned by caring for others

The Study Context

Bupa Cromwell Hospital, based in west London, served as the epicentre of this particular study especially in relation to data collection. Being in operation since 1981, the hospital is a leading private healthcare provider with over 120 beds and an estimated 400 top-of-the-range healthcare professionals and consultants (Bupa Cromwell Hospital, 2010). The hospital offers a collection of over 50 fields of healthcare provision, including oncology, paediatrics, general and specialized surgery, neurosciences, and genecology services.

As is the case in other healthcare facilities, Bupa’s care providers also become victims to compassion fatigue and other challenges regardless of the hospital’s employment of modern technology and innovative techniques. The researcher, during his practicum at the health facility, run more than 30 interviews with nurses, counsellors, and doctors with a view of coming up with requisite data needed to answer the key research questions.

Problem Discussion

The fact that compassion fatigue has become a global challenge affecting caregivers is not in question. The 21st century is characterized by provocative experiences not only in the medical fraternity, but also in other different spheres of life where individuals continues to emotionally and psychologically mirror the suffering or problems of others into their own thought systems and world views, in the process triggering a pandemonium of influences that negatively impacts on their well being (Compassion Fatigue, n.d.).

In the health sector, however, these influences are amplified by the very fact that caregivers are always in constant contact with patients who have all sorts of complications. The healthcare professionals are highly motivated to occasion a transformation in the lives of the suffering patients, and hence are more likely to share in the pain and suffering especially if they are unable to achieve their objectives (Ruysschaert, 2009).

Busy work schedules and family responsibilities in the fast-paced environment of modern times have served to further complicate issues for the caregivers. Negash & Sahin (2009) asserts that more than 40 percent of the nurses serving UK hospitals are unable to constantly be with their families and friends due to work-related restrictions. It is a well known fact that the comfort of family members and significant others can greatly assist the healthcare professionals to effectively deal with the overwhelming sensitivity and susceptibility to pain triggered by the close interactions between the caregivers and the clients (Mendenhall, 2006).

According to Bride (2007), a strong family relationship is one of the ingredients towards maintaining a healthy relationship between work-related factors and personal influences since an individual will always have other people around him to confide and share issues. While many systematic studies have been conducted to demonstrate how caregiver-client interactions cause the professionals to experience compassion fatigue, few have concentrated on how family issues as triggers of compassion fatigue affect the careers of caregivers. It is this gap that the study sought to fill.

The Study Objectives

The general objective of this study was to critically evaluate how family related variables conflict with work duties to exacerbate compassion fatigue among care givers. The following were the specific objectives:

- To undertake a deep analysis on how family responsibilities and career obligations acts to fuel compassion fatigue among healthcare professionals

- To develop a framework that could be used by caregivers to actively recognize the symptoms of compassion fatigue so that proper intervention measures are taken to assist the caregivers

- To develop a framework that could be used to create awareness to family members about the experiences of caregivers so that they could be actively engaged in assisting the caregivers deal with compassion fatigue rather than acting as triggers.

Research Questions

This particular study was guided by the following research questions

- What is the relationship between family responsibilities, career obligations, and compassion fatigue among healthcare professionals?

- How can compassion fatigue be recognized from other challenges facing caregivers?

- What could be done by family members and other stakeholders in helping the caregivers cope with overbearing levels of compassion fatigue?

Significance of Study

The vale of this study can never be underestimated. Compassion fatigue have far-reaching ramifications on the lives of caregivers, not mentioning the fact that it compromises their thought systems, attitudes, and worldviews to levels that reinforces unproductiveness, inadequacies, and lack of purpose in the workplace ( McCann & Pealman, 1990). As such, any study that attempts to generate objective strategies towards dealing with the condition is welcome.

In this perspective, this study came up with a body of knowledge on how family-related variables could be brought onboard in an attempt to assist caregivers to manoeuvre through the many challenges presented by the practice in general and compassion fatigue in particular. In addition, this particular study shed light on job related variables that combine with family influences to trigger an upsurge of compassion fatigue, not mentioning the fact that this study highlighted mechanisms that could be employed effectively to harness these variables towards developing approaches that could be used by caregivers to cope with compassion fatigue.

Literature Review

Introduction

Healthcare professionals play a fundamental role in the physical, emotional, psychological, and spiritual care of clients under their care (Aycock & Boyle, 2009). Although many caregivers perceive their duties as a calling, few are prepared for the physical and emotional drain that stem from their close connections with the clients and their families, not mentioning the fact that majority of the caregivers are unprepared on how to balance their demanding work schedules and family life (Klaus, 2005).

Consecutive studies reveal that both clinical scenarios and family pressures can elicit extreme emotional distress on the part of caregivers, occasioning a scenario whereby the professionals feel totally subdued and unable to cope with the demands of offering services in a healthcare setting. Nurses, in particular, are deeply disturbed by the special rapport they establish with patients in the line of duty, especially if they are unable to change the status of a patient’s illness in the event of a terminal illness. According to Aycock & Boyle (2009), “moral distress evolves when workplace barriers prevent nurses from carrying out what they believe to be ethically appropriate courses of action (p. 183). This breakdown often leads to compassion fatigue.

Definition of Compassion Fatigue

Compassion fatigue can be described as a state of physical, psychological, and mental collapse, where an individual feels totally depleted, tired, hollow, helpless, desperate, and even sceptical about himself, his work life, family life, and the overall state of the world (Alkema et al, 2008). It is a type of secondary traumatic stress disorder. In general settings, it can be argued that assisting others puts someone in direct contact with the experiences and lives of these individuals. Accordingly, your empathy for those you assist occasions both positive and negative characteristics.

On the one hand, assisting others is always viewed as powerful and fulfilling while on the other, it may lead to compassion fatigue, a scenario which is potentially dangerous to the helper (Figley, 1995). In the event that this occurs in a healthcare setting, caregivers experience ethical, psychological, and moral distress, not mentioning the fact that they tend to recognize the existence of frustration, tension, and discontent with their career obligations (Aycock & Boyle, 2009). Benson & Magraith (2005) asserts that many caregivers enter the practice with strong beliefs that they will be able to make an impact on the lives of clients. However, as the beliefs become eroded, the caregivers may be besieged with a sense of frustration, failure, desperation, and responsibility.

Compassion Fatigue and Burnout

In many instances, compassion fatigue is used interchangeably with ‘burnout.’ Experts, however, believe that the two terms stands for different conditions although there are largely used to describe the physical, psychological, and emotional responses experienced by individuals who are actively engaged in assisting others deal with their own problems. Compassion fatigue comes as a natural outcome of working with individuals who are going through stressful events, and mostly develops as a result of the caregivers’ exposure to the clients’ life occurrences combined with their own compassion for the patients (Benson & Magraith, 2005).

The authors posit that health professionals “…see the full range of ‘difficult’ patients – the acutely mentally ill, the traumatized, the dying, those with chronic illness, the ‘heart sink’ patient, and the socially disadvantaged” (p. 497). These experiences may lead to compassion fatigue, and symptoms of the condition include a sudden feeling of helplessness, bewilderment, isolation, tiredness, dysfunction, overwhelmed by work, and incapacity of effecting successful client outcomes.

On the other hand, ‘burnout’ is the “physical, emotional and mental exhaustion caused by long term involvement in emotionally demanding situations [and] contributing factors include professional isolation, working with difficult client population, long hours with limited resources, ambiguous success, unreciprocated giving, and failure to live up to one’s own expectations” (Benson & Magraith, 2005, p. 497).

Symptoms of ‘burnout’ include depression, scepticism, boredom, loss of empathy and discouragement. There exist several differences between the two concepts though their description appears to address similar conditions. First, complete and swift recovery for compassion fatigue can be achieved if the condition is addressed in the early phases. On the contrary, burnout can be persistent, and full recovery is often difficult (Benson & Magraith, 2005, Alkema et al, 2008). Second, compassion fatigue occurs suddenly while ‘burnout’ is often prolonged and may occur in phases.

It is indeed true that both empathy and compassion are central to maintaining a workable therapeutic association with patients in the delivery of efficient and high quality medical care. Some caregivers, however, extend this provision “…to a feeling that there is an ethical obligation to sacrifice their own needs for the needs of their patients…It is those who have enormous capacity for feeling and expressing empathy who tend to be more at risk of compassion fatigue” (Benson & Magraith, 2005, p. 498). Consequently, the most susceptible caregivers to a succession to full-scale ‘burnout’ are those who take their compassion to the farthest extreme and perceive themselves as redeemers. This therefore means that early detection of compassion fatigue may greatly assist to prevent burnout.

Phases of Compassion Fatigue

Researchers are in agreement that people afflicted with compassion fatigue characteristically go through four stages. In the first phase, known as the Zealot phase, the caregiver is overly committed, available, and always puts in extra hours to make a difference. The caregiver’s enthusiasm is unrelenting in this phase, not mentioning the fact that he is always ready to volunteer his assistance (Wee & Myer, 2002). The irritability phase comes second in the line, and heralds a period where the caregiver begins to avoid contact with the client in addition to experiencing lapses of concentration. The distractions may include daydreaming and distancing oneself even further from family relations and friends. The use of humour is unequivocally restrained during this phase.

Further on, the caregiver is initiated into the withdrawal phase, which entails loss of interest and passion for work, stress or fatigue, and loss of zeal for assisting others. The caregiver begins to neglect family members, co-workers, patients, not mentioning the fact that one also begins to neglect his or her own wellbeing (Wright, 2004). The last phase, known as the zombie phase, brings in a situation where despondency and despair turns into a deep-seated range. In addition to becoming totally incompetent and less tolerant to other people’s viewpoints, the individual begins to loath other people, including family members and co-workers (Wee & Myer, 2002). Put in another way, the caregiver experience feats of complete disparagement for patients and clients.

Theory: The Trauma Transmission Model

Researchers have successfully fronted a multiplicity of conceptual frameworks that could be used to explain the nature compassion fatigue and how it is different from other causes of trauma in the healthcare setting (Stewart, 2009). This section aims to offer a summary of the Trauma Transmission model due to its relevancy and applicability to caregivers. It is important to note that this particular study assumes family responsibilities and patients are major causes of compassion fatigue for caregivers.

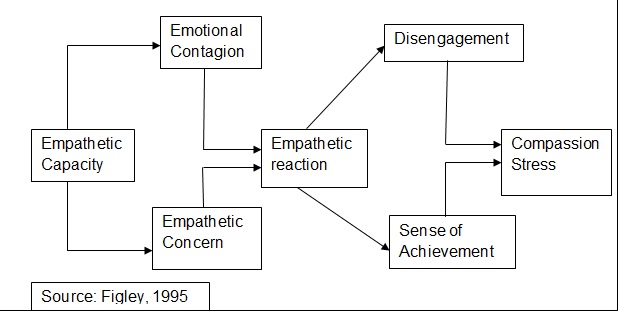

The Trauma Transmission Model, credited to C.R. Figley, attempts to explain how fatigue or stress is transmitted in addition to demonstrating how some caregivers develop compassion exhaustion while others seems resistant to the fatigue. The model use compassion stress factors on one hand and compassion fatigue factors on the other in an attempt to understand the trauma and difficulties caregivers experience by identifying and associating with patients or clients with deep-seated difficulties (Figley, 1995). The fundamental facet of this model under the compassion stress component is empathy, which is unequivocally divided into three components – empathetic capability, empathetic concern, and empathetic reaction (Figley 1995; Craig & Sprang, 2010).

Empathetic capability relates to the caregiver’s capacity to be aware of the pain and suffering of others to a point of transmitting absolute positive regard and authenticity. This realization links the caregiver to empathetic concern, a scenario which constitutes a deep enthusiasm to respond to the victim’s problems. According to the model, a caregiver must have empathetic capacity beforehand for him to open up and exhibit empathetic concern to the client (Figley, 1995; Stewart, 2009). The model further asserts that empathetic response or reaction is the combination of the caregiver’s empathetic capacity and empathetic concern, and evaluates the level of effort initiated by the caregiver in helping the client or patient manage the pain and suffering of the trauma (Figley, 1995).

The model makes mention of ‘emotional contagion,’ which Figley (1995) depicts as “…experiencing the feeling of sufferers as a function of exposure to the sufferer” (p. 252). The model connects the concept of emotional contagion to the caretaker’s empathetic capacity, postulating that this link subsequently occasion compassion stress. The caregiver, however, can experience the right kind of satisfaction from the relationship with the patient or client if he or she disembarks from the relationship at the opportune moment (Stewart, 2009). Part one of the model – the compassion stress component – is illustrated in the diagram below.

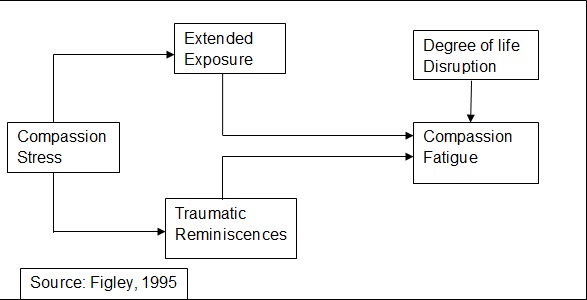

In the second component of Trauma Transmission Model, Figley (1995) asserts that the development and ballooning of compassion fatigue in caregivers is mainly a function of four interrelated variables, namely intensity of compassion stress, protracted exposure to the patient or client, traumatic recollections or reminiscences, and degree of life disruption.

According to the theorist, extended exposure to traumatic incidences happens due to the caregiver’s perception that they have to incessantly take care of the patients or clients. As such, the caregiver feels individually responsible for the client, and is therefore incapable or unwilling to curtail their compassion stress (Craig & Sprang, 2010). Subsequently, traumatic reminiscences occasion secondary symptoms and other negative-oriented responses on the caregivers. Figley (1995) further postulates that compassion fatigue turns into a natural occurrence when the above circumstances exist. The second component of the model is represented in the diagram below.

Although this model continues to assist stakeholders understand the different factors that come into play to trigger compassion fatigue, it has been faulted for being narrow in focus, complex in nature, and deficient in describing the contextual and circumstantial influences in the conveying of traumatic or stressful material (Craig & Sprang, 2010).

Compassion Fatigue and Family Responsibilities

Work and family-related obligations sometimes continually conflict as individuals find that there is barely enough time to attend to both obligations satisfactorily (Szabo, 2006). In the health sector, this situation is worsened by the fact that caregivers have to spend considerable amount of time away from their families as they attend to patients with a multiplicity of problems. In many instances, they are denied the warmth that is normally found within a family setting yet they are exposed to situations that serve to heighten their anxiety levels (Bride, 2007; Mendenhall, 2006).

Szabo (2006) asserts that family responsibilities, and the uncomfortable realization that health professionals may not be in total control of what is going on within the family context due to the nature of their work, are known causes of compassion fatigue and burnout among caregivers. Negash & Sahin (2009) postulates that such compassion fatigue negatively influences the caregiver-patient therapeutic relationship as well as general treatment outcomes in addition to influencing his or her personal life and family connections.

Tyson (2007) argues that compassion satisfaction – the capability of caregivers to obtain a great sense of value and meaning from their work – can aid to lighten existential conflicts and pressures occasioned by family responsibilities in the workplace. Family related stress is further aggravated by poor self-care on the part of the caregiver, previous unresolved trauma, incapability or unwillingness to control work stressors, and lack of contentment for the work (Figley, 1995). Tehrani (2007) posits that the caregiver should at all times be aware and acknowledge the limitations occasioned by the nature of the job and family responsibilities to deal effectively with compassion fatigue. In all endeavours, discipline in daily responsibilities and obligations must be maintained.

Signs and Symptoms of Compassion Fatigue

In the healthcare profession, caregivers involved in offering care soon find themselves developing traumatic feelings, anxiety, excessive empathy, and irrational life demands (Abendroth & Flannery, 2006). Physically, the caregivers may experience chronic feelings of exhaustion and low energy, insomnia, loss of appetite, frequent headaches and stomach-aches, physical anxiety or retardation, substance or alcohol abuse, and recurrent spells of sickness (Mendenhall, 2006). Psychologically, the caregiver feels greatly beleaguered by the volume, nature and content of his work, and is irritable at the slightest provocation. Other psychological symptoms include compulsive behaviours, recurrent nightmares, sadness, apathy, and deep feelings of denial (Figley, 1995; McCann & Pealman, 1990).

Organizationally, the caregiver is totally or partially unable to meet their professional, family, and personal responsibilities, not mentioning the fact that the individual often feels scattered and blurred. Other organizational symptoms include negativism towards management, lack of vision, high rates of absenteeism, outbursts of destructive behaviour, and spirited resistance to change (Figley, 1995). The caregiver’s relationship with clients and family members is also affected to the core due to a sudden lessening of their empathy for others. The caregiver may also develop feelings of numbness towards patients, cynicism, and pain towards family members (Mendenhall, 2006)

Management of Compassion Fatigue

It is expected that most caregivers will at times go through signs and symptoms of compassion exhaustion as a normal response to the nature of their work. Some caregivers, however, may experience compassion fatigue in ways that are so ruthless as to impede their therapeutic effectiveness in addition to their overall physical and mental wellbeing (Bride et al, 2007). It is for this fundamental objective that ongoing monitoring and management is necessary. There exist some tools that could be used effectively to examine the presence of compassion fatigue instead of waiting for the caregivers and other professionals to become symptomatic (Tehrani, 2007). Below, one of the techniques is discussed.

Compassion Fatigue Self-Test

The Compassion Fatigue Self-Test basically entails a self-report evaluation scale encompassing three subscales – compassion fatigue or exhaustion, burnout, and compassion satisfaction. In most occasions, the test is scored using a Lickert-type measurement scale, implying that 1 is equated to ‘not at all’ or ‘least affected’ and 5 is equated to ‘very often’ or ‘most affected’ (Bride at al, 2007). The score is then summed up to give a clear picture for the scale. Respondents are required to rate items using their frequency of occurrence. According to Shauben & Frazier (1998), the scores for compassion fatigue should be deduced as follows:

- 26 or below = exceptionally low risk

- 27-30 = low risk

- 31-35 = average risk

- 36-40 = elevated risk

- 41 and above = exceptionally high risk

For simple analysis, however, the items can be rated in a scale of 1 to 10 as follows: 1 = never experienced; 5 = occasionally experienced; and 10 = repeatedly experienced (Bride et al, 2007). In Figley (1995) scale, higher scores signify greater threat for compassion fatigue, with the cut-off point being calibrated at 31. This implies that any caregiver or other professionals scoring above 31 is suffering from a moderate or relentless compassion fatigue. This scale has been used successfully in many studies to measure compassion fatigue (Ortlepp & Friedman, 2001).

With early evaluation, caregivers and other professionals have the opportunity to alter the discomfort caused by compassion fatigue into an occasion for personal growth and development. According to Radey & Figley (2007), any professional management or support model aimed at addressing compassion fatigue should principally focus on boundary maintenance, individual self-care, good professional training, and good supervision.

While faced with this situation, individuals should take more fluids, eat a balanced diet, undertake physical exercises to stimulate both body and brain, and try to live positively (FoundationCoaching, 2008). When dealing with ‘difficult’ patients or clients, it is always helpful to relax and look at issues objectively rather than try to mop up all the problems that your patient or client is experiencing (Mendenhall, 2006). It is in order to learn how to do away with negative emotions, not mentioning the fact that it is always fundamental to establish a set of rules to guide your relationship with patients and clients. When all this is done, caregivers should not experience any problems thriving in the medical field as compassionate professionals.

Methodology

Introduction

This chapter outlines the nature and design of this research in addition to describing the population and sample size, instrument design, processes used in data gathering, how the data was analyzed, and ethical considerations.

Research Design

This particular study utilized a qualitative research design in evaluating how individuals, especially caregivers, could be assisted to deal with compassion fatigue. The researcher employed a descriptive qualitative approach since the subjects were only evaluated once though at different times during the researcher’s stay at Bupa Cromwell Hospital. Maxwell (2005) suggests that qualitative research designs are preferred when the researcher is interested in evaluating human behaviour, values, attitudes, preferences, and perceptions, not mentioning the fact that the designs are mostly utilized to generate leads, notions, and concepts which can then be used to prepare a pragmatic and testable hypothesis.

Qualitative research designs can use either the case study approach or survey design to collect the requisite data (Maxwell, 2005). The researcher chose to employ the survey design using face-to-face semi-structured interviews. Qualitative approaches are tremendously helpful when a subject or phenomena under study is too multifaceted to be responded to by a simple yes or no as it is the case with evaluating compassion fatigue (Maxwell, 2005). In this particular case, the researcher needed to get to the core of family and work related issues seen as triggers for compassion fatigue among caregivers. The second advantage of qualitative approach is that data validity is not reliant upon the size of sample as it is the case with quantitative research methods

Population and Sample Size.

The population for this particular study included healthcare professionals such as nurses, hospital counsellors, and doctors. As mentioned elsewhere, qualitative research designs do not entirely depend on the size of sample as it is evident that a small sample size is capable of generating a lot of data as is the case in case studies (Maxwell, 2005). The researcher conducted more than 30 interviews with the mentioned professionals during her stay at Bupa Cromwell Hospital, but narrowed her scope for the required information to data received from 5 nurses, 5 hospital counsellors, and 2 doctors. The researcher used purposive sampling techniques to come up with the sample size required for the study. In purposive sampling, subjects are surveyed based on their understanding of the phenomena under study (Maxwell, 2005)

Data Gathering Instrument

Data for this particular study was gathered using face-to-face semi-structured interviews, where the researcher posed a mix of standard and unstructured questions in an attempt to evaluate the major objectives of the study. The researcher adopted some components of the Compassion Fatigue Self-Test and incorporated them on the interview schedule to get a vivid glimpse of how compassion fatigue affected caregivers in Bupa Cromwell Hospital. Maxwell (2005) posits that face-to-face interview have a definite advantage over other data collection procedures in that not only does the procedure enable the researcher to create rapport with the subjects, hence gaining their cooperation, but it also allows the researcher an opportunity to probe further for more information using the unstructured items

Data Analysis

Qualitative studies often yield large volumes of thoughts, attitudes, and opinions, and this particular study was no exception. As such, the researcher used content analysis technique for purposes of data reduction, data presentation, and finally, conclusion drawing and verification (Sekaran, 2006). This is the simplest and most used qualitative technique, especially in healthcare research. According to Stevens (2003), “…content analysis is the systematic description of behaviour asking who, what, where, why, and how questions within formulated systematic rules to limit the effects of analyst bias…

It is the preferred technique for analysing semi-structured interviews” as is the case in this study (143). The first stage entailed reducing and filtering data to enable the researcher concentrate on data that was deemed useful. Afterwards, the data display or presentation process enabled the researcher to simplify data that was deemed complex. Finally, conclusion drawing and verification was done to come up with objective conclusions and verify the validity of data collected (Sekaran, 2006).

Research Ethics

According to Saunders et al (2007), “…ethics refers to the appropriateness of your behaviour in relation to the rights of those who become the subject of your work, or are affected by it” (p. 178). In addition to requesting for permission from the management to conduct the interviews within the hospital’s premises, the researcher also took time to explain to the subjects the nature and purpose of the study she was involved in, not mentioning the fact that the researcher kept the subjects in the know about their rights, especially the right to informed consent and the right to privacy.

Findings

Introduction

This section presents the findings of the study that aimed to evaluate how family related variables conflict with work duties to exacerbate compassion fatigue among healthcare professionals. The study was conducted at the London Bupa Cromwell Hospital. Although the researcher conducted over 30 interviews while doing her practicum in the health facility, interest was accorded to the respondents who narrated how family-related issues affect their career obligations. Below, the results of selected interviews are presented in brief.

Results

The results contained herein are from interviews conducted with 5 nurses, 5 hospital counsellors, and 2 doctors engaged in giving care at London Bupa Cromwell Hospital. Several repetitive themes were noted after the analyses of the qualitative data. These themes are highlighted below

- Most of the caregivers are virtually separated from their families, and this makes it difficult for them to balance between work obligations and family related responsibilities. In most cases, the caregivers communicate with family members using telephone conversations rather than physical contact

- Health professionals spend most of time caring for patients, and have little time left for family or leisure. In some instances, the caregivers are recalled from their off-work hours to take care of emergencies while some work for long hours in a single shift. The long periods of time spent by the professionals offering care to the patients leads to burnout. One of the nurses interviewed had this to say:

“…It is common to work an 18-hour shift. Sometimes you are supposed to be resting but a phone call comes through and you have to rush back to the hospital especially during emergencies. On the other hand, some weeks may be good but the burnout you experience makes it difficult to have quality time with loved ones…”

- Majority of the caregivers loves their work and gains great satisfaction from offering care. Indeed, a significant proportion of the caregivers say they joined their respective professions for personal reasons, mostly to be able to care for a loved one. The tough demands of the work, however, leaves them totally exhausted and at risk of falling prey to compassion fatigue

- In addition to the tough work demands, most caregivers are the sole breadwinners for their families. A significant proportion of the health professionals are also responsible for taking care of their sick family members, impacting heavily on their capacity to provide efficient services at the hospital. In most instances, the family members of the caregivers suffer from terminal illnesses, further heightening the caregivers’ stress levels since they are faced with difficult situations both in hospital and home

- Some caregivers are stressed by the very fact that they are unable to offer guidance and support to their young children since they spend most of their time caring for patients at the hospital. One of the nurses interviewed lamented:

“…because of the long work hours and changing shifts, I can’t say I have always been there for my children and to watch them grow…”

- The burnout and compassion fatigue experienced by caregivers makes it difficult for them to have quality time with family members even in good times

- Some caregivers have already formed the notion that burnout and stress are almost inevitable in the healthcare profession owing to the nature of work. The following assertion by one of the nurses best captures the mood:

“…burnout is almost inevitable in the nursing profession. Too many patients, but too few nurses. My situation is however made more difficult because I have to take care of my sister. Her epileptic attacks are frequent and therefore I cannot leave her unattended to…”

- Family responsibilities, especially caring for sick family members and financial obligations distract the caregivers from offering quality services at their workstations due to compassion fatigue and burnout

- Some caregivers, specifically counsellors, are unable to perform their work-related duties efficiently due to lack of collaboration from their counterparts. During the interview process, a hospital counsellor agued:

“…the main challenge [we face] is the lack of collaboration from the general practitioners. Counselling requires support and team work from physicians and other care providers without which it may be difficult to assist a client heal completely…”

- It is clearly evident that not only do family-related responsibilities affect the caregivers in delivery of service at the hospital, but also work-related obligations affects how caregivers are able to function at the family context. This increases burnout and compassion fatigue

- Some caregivers, specifically counsellors, do not have the necessary resources required to provide care effectively. This functions to increase burnout

- Caregivers find it extremely challenging to balance between work, family responsibilities, and the urge to enrol for further studies, workshops, and seminars to enable them handle their multifaceted functions in offering care

- The job demands in the healthcare profession are always stressing due to the high patient turnover and other roles taken by the caregivers such as teaching, administration functions, etc. This leaves the professionals with little time for themselves and their families. One doctor noted:

“…high job demands and high patient turnover make it difficult for me to balance my work with my family obligations. Most of the days we work long hours and sometimes we are forced to go back to the hospital while on rest. Besides working, I also teach at one of London’s medical teaching hospitals thus have even little time for my family or myself. Indeed, I can never be certain that I will rest on such a day or such a time. It is really hectic…”

Discussion and Analysis

The negative effects caused by compassion fatigue have elicited a global outcry for effective measures to be put in place to assist professionals, especially caregivers, deal with the situation. According to Ruysschaert (2009), it is not easy to separate the caregivers from the everyday stress and difficult situations as they go about providing care since interacting with patients in difficult situations is a fundamental prerequisite for the profession. Indeed, the study results have revealed that caregivers view stress and excessive burnout as normal components of their professional life.

Aycock & Boyle (2009) asserts that caregivers play a fundamental role in the physical, emotional, psychological, and spiritual care of clients under their care. On the other side, Szabo ( 2006) asserts that work and family related obligations are in constant collision course in some professions as individuals come to terms with the fact that there is barely enough time to attend to both obligations satisfactorily. As such, a solution to compassion fatigue cannot be found in requesting the caregivers to avoid duties that lead to stressful situations; rather, the solution lies in coming up with effective strategies that will enable the caregivers deal with the stressful situations, may they be job related or family oriented.

Aycock & Boyle (2009) are of the opinion that “…moral distress evolves when workplace barriers prevent nurses from carrying out what they believe to be ethically appropriate courses of action” (p. 183). This statement has been reinforced by the findings of this particular research in that caregivers were found to offer poor services when work obligations restricted them from extending care to sick family members. As such, it can be argued that the appropriate course of action, according to the caregivers, is to first offer care to their sick family members before extending the same care to patients in health facilities. The nature and rules of their work, however, makes such arrangement untenable, leading to compassion fatigue.

The caregivers feel greatly indebted to provide care for their loved ones back at home but they are unable to do so due to their busy schedule at the healthcare facilities. On the other hand, the caregivers undergo strenuous situations on a daily basis attempting to care for the patients and clients who may be nursing deep-seated problems. This conflict of interest occasions compassion fatigue, whereby healthcare professionals start to experience feelings of pain, suffering, and anguish of the patients, clients, and family members for whom they care (Compassion Fatigue, n.d.). According to Ruysschaert (2009), “…caregivers and healthcare workers are more at risk of burnout as they face human suffering and absorb this other people’s pain” (p. 160).

Benson & Magraith (2005) asserts that many caregivers enter the practice with strong beliefs that they will be able to make an impact on the lives of clients. This assertion is also reinforced by the study findings, which reveals that many caregivers enter the profession for personal reasons, specifically to learn the necessary skills that will enable them take necessary medical care for sick family members and other patients experiencing difficult situations. However, as the beliefs and interests become eroded by excessive workloads and conflicts between job-related obligations and family responsibilities, the caregivers become besieged with a sense of frustration, failure, desperation, and responsibility.

They caregivers become completely embroiled in compassion fatigue as they attempt to redeem other people, including family members, from their suffering and difficult situations. According to Bride (2007) & Mendenhall (2006), this situation is further complicated by the fact that most caregivers have to spend considerable amount of time away from their families, hence denying them the warmth that is normally found within a family setting on one hand and exposing them to situations that serve to heighten their anxiety levels on the other.

The Trauma Transmission Model explained in section two of this particular study can be used to depict how work-related obligations combine or work in conflict with family responsibilities to occasion compassion fatigue in caregivers. This model use compassion stress factors on one hand and compassion fatigue factors on the other in an attempt to understand the trauma and difficulties caregivers experience by identifying and associating with patients or clients with deep-seated difficulties (Figley, 1995).

From the study findings, it is evidently clear that all caregivers have empathetic capability – a capacity to be aware of the pain and suffering of others. The melodramatic experiences of the caregivers and their family members lead to empathetic concern, a scenario which constitutes a deep enthusiasm to respond to the victim’s problems (Stewart, 2009). Here, it can be argued that the caregivers’ empathetic concerns for family members and other family-related responsibilities weigh heavily on the caregivers to a point of compromising their services within the hospital setting.

The Trauma Transmission model makes mention of ‘emotional contagion,’ which Figley (1995) depicts as “…experiencing the feeling of sufferers as a function of exposure to the sufferer” (p. 252). This concept is also demonstrated vehemently in the experiences offered by the caregivers during the interview when they argue that they are unable to concentrate on their core duties of provision of care after they remember their suffering members of family.

The model further connects the concept of ‘emotional contagion’ to the caretaker’s empathetic capacity, postulating that this link subsequently occasion compassion stress. As such, it can be argued that family related responsibilities such as caring for sick family members and financial obligations contributes as much weight to compassion fatigue as the stress linked to caring for sick patients in the hospital setting. The caregiver, however, can experience the right kind of satisfaction from the relationship with the patient or client if he or she disembarks from the work-related or family-related relationships at the right moment (Stewart, 2009).

This particular study has been successful in demonstrating the intricacies involved in dealing with compassion fatigue. The Trauma Transmission model itself shows how compassion fatigue is a function of four interrelated variables – intensity of compassion stress, protracted exposure to the patient or client, recollections or reminiscences, and degree of life disruption (Figley, 1995). The study findings are clear that unmitigated exposure to family-related stress as well as stress resulting from interactions with patients takes a toll on the physical, emotional, psychological, and spiritual wellbeing of caregivers.

The worse part is that, in almost all instances, the caregivers feel individually responsible for the family members, and are therefore incapable or unwilling to curtail the relationships that lead to stress (Craig & Sprang, 2010; Pines & Aronson, 1989). This, according to Figley (1995), causes them to recollect the traumatic experiences affecting their family members even further, a situation that leads to secondary trauma symptoms and other negative-oriented responses on the caregivers.

It is a well known fact that health facilities should be at the forefront of providing interventions that will enable the caregivers to function optimally in the provision of care. However, as the study findings reveals, this is not always the case as some interviewees complained of lack of resources while others cited lack of acknowledgement for their contributions. According to Lauterbach & Vrana (2001), such loopholes only assist to aggravate the issues facing caregivers, ultimately leading them to compassion fatigue lapses.

According to Wright (2004), lack of recognition for work done or services offered leads the caregivers into the withdrawal phase of the compassion fatigue spectrum, which basically entails loss of interest and passion for work as well as loss of zeal for assisting others, including family members. According to Negash & Sahin (2009), such type of burnout and compassion fatigue negatively influences the caregiver-patient therapeutic relationship as well as general treatment outcomes in addition to influencing his or her personal life and family connections.

According to the study findings and the discussions highlighted above, it is now evidently clear that compassion fatigue affects all health professionals regardless of field of specialization. The reasons fronted by the nurses, health counsellors, and doctors were almost similar across board – that heavy work schedules and family responsibilities are to blame for the excessive burnout and compassion fatigue.

It cannot escape mention that the professionals interviewed extended their official services at the hospital into their own families as they were expected to care for sick family members. This further aggravated the situation, making the health professionals to operate like mechanical machines as they attempted to juggle work functions with family responsibilities. According to Craig & Sprang (2010), such a scenario has been doing rounds at our health facilities, and exposes the failure of the existing systems to contribute adequate human capital and resources for the profession.

A new challenge in lack of collaboration from general practitioners was registered by health counsellors as a likely cause for compassion fatigue. This challenge, though not mentioned by the nurses or doctors interviewed, exposes a loophole that could have far-reaching ramifications if intervention measures are not carried out. Benson & Magraith (2005) asserts that professionals need to feel cared for and appreciated by recognizing their contributions to the wellbeing of the clients.

Nevertheless, the complaints raised by the counsellors suggest a gap in the provision of all-inclusive care to the patients since the counselling component is as important as the part played by general practitioners. It is therefore prudent to argue that lack of recognition and collaboration not only enhances compassion fatigue among the concerned professionals, but also limits the efficient all-inclusive provision of care.

Doctors, due to the fact that they must be in the know about current trends in the practice, reported experiencing burnout and compassion fatigue from juggling work-related functions and studying. This is in addition to the family responsibilities that placed a heavy burden on the shoulders of all professionals. Again, this portrays deep-seated problems in shortage of personnel. It becomes challenging for doctors to undertake educational or research activities since there are no ready replacements. It is certain that doctors intending to further their studies have to juggle work functions with family responsibilities and their educational requirements, resulting in massive burnouts and compassion fatigue. This need not be the case.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Conclusions

This particular study sought to evaluate the notion of compassion fatigue among caregivers and what could be done to assist the members of the healthcare profession in dealing with the condition especially from the family perspective. Several conclusions can be deciphered from the study. The study revealed that caregivers carry family-related obligations in high esteem, and are frequently distracted by responsibilities arising from other avenues apart from work-related obligations. It is evidently clear that many caregivers are struggling under the heavy weight of family responsibilities, which include taking care of sick family members , financial obligations, and providing moral support to their children and dependents. This has served to enhance compassion fatigue among the caregivers

From the study, it is also evidently clear that many caregivers carry their roles from the hospitals into their homes as they have to take care of sick family members. In the hospital, the caregivers do not have the peace of mind as they continually think about how their sick relatives are fairing at home. In the same vein, the caregivers do not enjoy quality time at home since they can be recalled anytime to take care of an emergency. This conflict of interests has been largely blamed for causing compassion fatigue or worsening the situation among healthcare professionals.

It can also be concluded that many caregivers enter the practice with strong beliefs that they will be able to make an impact on the lives of clients. However, the demands of their jobs coupled with never-ending family responsibilities make them realize that there is a difference between their fondly-held dreams of assisting others and the harsh reality on the ground. In most occasions, this realization makes caregivers to become besieged with a sense of frustration, failure, and desperation. In line with this, it can also be concluded that most health facilities lacks the mechanisms and interventions needed to assist the caregivers deal with compassion fatigue.

Further a field, it can be concluded that most caregivers spend considerable amount of time away from their families, hence denying them the warmth that is normally found within a family setting. This only serves to facilitate compassion fatigue. From the study, it is also evidently clear that nearly all caregivers have empathetic capability, a distinct capacity to be aware of the pain and suffering of others. This capacity makes them to be overly concerned about the issues affecting their family members, hence serving as fertile grounds for compassion fatigue.

In line with this, it is evidently clear that family-related responsibilities such as caring for sick family members and financial obligations contributes as much weight to compassion fatigue as the stress linked to caring for sick patients in the hospital setting. Still, lack of recognition for work done or services offered have been shown to lead caregivers into compassion fatigue. Finally, the study has demonstrated that caregivers have the potential to experience the right kind of satisfaction from the relationship with the patients or family members if they know how to disembark from the relationships at the right moment.

Recommendations

Several recommendations can be fronted to remedy the situation. It has been proved beyond reasonable doubt that many caregivers are struggling a great deal trying to balance family responsibilities and work duties. For the caregivers with sick family members, it can be recommended that they join support groups where they could share with other caregivers who are also taking care of sick family members at home. This can go a long way into lifting the heavy burden associated with caring for sick family members. Support groups are also instrumental in assisting the care givers cope with the demands as they go about fulfilling their official duties.

Second, the management of health facilities should come up with flexible time schedules to give the caregivers adequate time for relaxing and taking care of their families. Indeed, annual leaves for caregivers should be extended to give the professionals adequate time for rest. However, this can only be achieved if the government and other stakeholders employ more caregivers in health facilities. Strategies to curtail the present shortage of health personnel must therefore be put in place to ensure that caregivers are not recalled from their off-times and leave days to take care of emergencies.

Family support is required if the caregivers are to successfully fight compassion fatigue. It is true that caregivers, like anybody else, need to care and be responsible for their families. However, the family members must be made aware that caregivers are busy professionals due to the nature of their work, and as such, they may not be available to deal with family emergencies at all times. Such an understanding is necessary to lift the heavy burden of family responsibilities off the shoulders of caregivers and hence curtailing compassion fatigue. This arrangement will definitely enable the caregivers to concentrate on their primary roles.

On their part, the caregivers should take the initiative of lessening compassion fatigue by employing or contracting professional caregivers to take care of family members, especially those suffering from terminal illnesses. This will avail the caregivers much needed time for relaxing and taking care of other obligations. Lastly, it should be the function of the health facilities to ensure that all the needed support – material or non material – is accorded to the health professionals as they go about their duties of providing care. This will go a long way to reduce the physical, mental, psychological, and emotional burnout and fatigue experienced by the professionals

Reference List

Abendroth, M., & Flannery, J. (2006). Predicting the risk of compassion fatigue: A study of hospice nurses. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing 8(6): 346-356.

Alkema, K., Linton, J.M., & Davies, R. (2008). A study of the relationship between self care, compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnout among hospice professionals. Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life and Palliative Care 4(2): 101-119.

Aycock, N., & Boyle, D. (2009). Interventions to manage compassion fatigue on oncology nursing. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing 13(2): 183-191.

Benson, J., & Magraith, K. (2005). Compassion fatigue and burnout: The role of Balint groups.Australian Family Practice 34(6): 497-498. Web.

Bride, B. (2007). Prevalence of secondary traumatic stress among social workers. Social Work 51(2): 63-70.

Bride, B., Radey, M., & Figley, C.R. (2007). Measuring compassion fatigue. Clinical Social Work Journal 35(2): 155-163.

Bupa Cromwell Hospital. (2010). Web.

Compassion Fatigue. (n.d.). Web.

Craig, C.D., & Sprang, G. (2010). Compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnout in a national sample of trauma treatment therapists. Stress & Coping 23(3): 319-339

Figley, C.R. (1995). Compassion fatigue as secondary traumatic stress disorder: An overview. In: C.R. Figley (Eds) Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized. London: Brunner-Routledge.

FoundationCoaching. (2008). The first few steps of extreme self care. Web.

Kraus, V.I. (2005). Relationship between self care and compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue and burnout among mental health professionals working with adolescent sex offenders. Counselling and Clinical Psychology Journal 2(1): 81-88.

Keltner, D., & Ekman, P. (1996). Affective intensity and emotional responses. Cognition & Emotion 10(2): 323-328.

Lauterbach, D., & Vrana, S. (2001). The relationship among personality variables, exposure to traumatic events, and severity of post-traumatic stress symptoms. Journal of Traumatic Stress 14(1): 29-44.

McCann, L., & Pealman, L.A. (1990). Psychological trauma and the adult survivor. New York Brunner/Mazel.

Maxwell, J.A. (2005). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, California. Sage Publications, Inc.

Mendenhall, T. (2006). Trauma-response teams: Inherent challenges and practical strategies in interdisciplinary fieldwork. Families Systems, & Health 24(3): 357-362.

Negash, S., & Sahin, S. (2009). Compassion fatigue in marriage and family therapy: Implications for therapists and clients. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 12(21): 373-382.

Ortlepp, K., & Friedman, M. (2001). The relationship between sense of coherence and indicators of secondary traumatic stress in non-professional trauma counsellors. South African Journal of Psychology 31(2): 38-45.

Pines, A.M., & Aronson, E. (1989). Career Burnout: Causes and Cures. New York: Free Press.

Radey, M., & Figley, C.R. (2007). The social psychology of compassion. Clinical Social Work 35(1): 207-214.

Ruysschaert, N. (2009). (Self) Hypnosis in the prevention of burnout and compassion fatigue for caregivers: Theory and Induction. Contemporary Hypnosis 26(3): 159-172.

Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornbill, A. (2007). Research methods for business students. London: Prentice Hall.

Sekaran, U. (2006). Research methods for business: A skill building approach, 4th Ed. Wiley-India.

Schauben, L.J., & Frazier, P.A. (1998). Secondary traumatic stress effects of working with survivors of criminal victimization. Journal of Traumatic Stress 16(2): 167-174.

Stevens, M. (2003), Selected qualitative methods. In: M.M. Stevens (Eds) Interactive textbook on clinical symptoms research. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stewart, D.W. (2009). Casualties of war: Compassion fatigues and healthcare providers. MEDSURG Nursing 18(2): 91-94.

Szabo, B. (2006). Compassion fatigue and nursing work: Can awe accurately capture the consequences of caring work? International Journal of Nursing Practice 12(2): 136-142.

Tehrani, N. (2007). The cost of caring – the impact of secondary trauma on assumptions, values and beliefs. Counselling Psychology Quarterly 20(4): 325-339.

Tyson, J. (2007). Compassion fatigue in the treatment of combat-related trauma during wartime. Clinical Social Work Journal 35(1): 183-192.

Wee, D.F., & Myer, S.D. (2002). Stress responses of mental health workers following disaster: The Oklahoma City bombing. In: C.R. Figley (Eds) Treating Compassion Fatigue. New York, NY: Brunner-Routledge.