Introduction

Music is an art that creates images by combining sounds and silence. It can serve as both an independent artist and as an accompaniment to other art forms. Although it might seem that in the latter case, music is secondary, it is a powerful tool the role of which is often crucial.

For instance, music is widely used in movies. Here, music can be diegetic and non-diegetic. Diegetic music originates in the plot; characters can hear it. It often indicates the place and time or peculiarities of the setting. Non-diegetic music is “background music” that communicates the psychological aspects of the story, coloring the actions that take place on the screen, showing the pace of on-screen events, and creating the atmosphere (“Diegetic Music’” par. 1-4). By utilizing the ways the human brain commonly interprets various combinations of sounds, music “directs attention, induces mood, communicates meaning, cues memory, heightens arousal and suspends disbelief, and… adds an aesthetic dimension” (Cohen, 17-18). Therefore, it can be argued that the art of cinematography would be crippled without music.

In our paper, we will consider three examples of movies: Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, Inception, and Interstellar, and describe some elements of music which are recurrent in these films.

Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone

Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (2001) is the first movie in the famous fantasy heptalogy. The film was directed by Christopher Joseph Columbus; the music was written by John Williams.

One of the major themes employed in the movie is “Hedwig’s Theme.” It represents the feelings and experiences the young boy has while entering the wizarding world (Webster 90). The theme creates the anticipation of something mysterious but benevolent. Despite being initially intended only for scenes with Harry’s owl, the theme was used in many parts in the movie, as well as in some of the following Harry Potter films (“John Williams Themes” par. 2).

The most distinctive instrument played in the theme is the celeste. The resulting sound is also electronically controlled, makes the music “literally unreal” (“John Williams Themes” par. 5). The theme begins with a high register, which then changes to a lower register; this usually happens in steps, but sometimes also in leaps.

The meter of the “Hedwig’s Theme” is three-beat. This causes “a feeling of elegance and grace” and the impression of lightness, which characterizes the magical world as it is often perceived by children (“John Williams Themes” par. 19). The tempo of the melody is moderate.

It is offered to split the “Hedwig’s Theme” into two sections; it is possible to plainly name them “A” and “B.” In the musical clip accompanying the article on the topic, the part “A” occupies the following intervals: 00:00-00:17, 00:45-01:01, 01:18-01:35 (“John Williams Themes” par. 3).

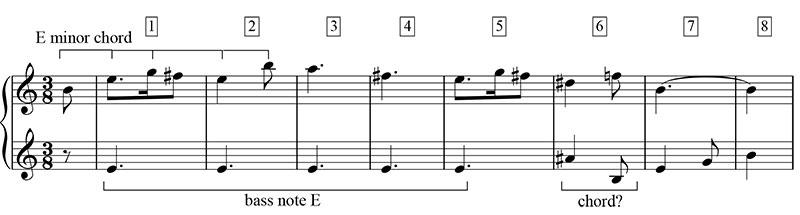

The Hedwig theme occupies the key of E minor. On the other hand, the chord progressions, in this case, are not characteristic of a minor key. If we consider Fig. 1, it is possible to note that the bars #1 and #2 show the E minor chord and that E is prolonged into the fifth bar; that gives us the key. On the other hand, an unusual chord appears in bar #6 unexpectedly (“John Williams Themes” par. 6):

It can be seen that the sixth bar employs the following sequence of notes: B-D#-F-A#. This sequence is analogous to the notes utilized in the dominant chord #7 of E minor, namely B-D#-F#-A. It is argued that by using F instead of F# and A# instead of A, the composer establishes an odd and unexplainable chord, which is suitable for the magical world of Harry Potter (“John Williams Themes” par. 7).

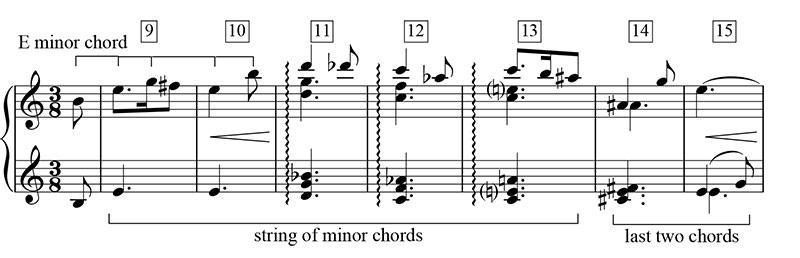

The same unusualness occurs in the next part of the section; as follows from Fig. 2, the ninth and tenth bars are the original E minor chord; in contrast, bars #11 and #12 give the music an entirely unexpected direction, for the three additional minor chords seem not to be connected to each other. This feature gives the listener the feeling of a fairytale mystery (“John Williams Themes” par. 8).

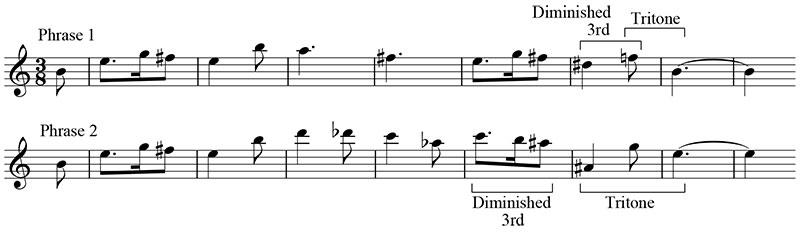

It should be noted that, while analyzing the melody of the section “A,” it might prove useful to break it into a pair of separate phrases (see Fig. 3); bars #1-5 only include the notes characteristic of E minor, whereas the bar #6 uncommonly employs the note F. It performs a double function: being a part of the odd dominant-like harmony in the given bar, it simultaneously produces unusual intervals in the melody. Being preceded by D#, this note F “takes the minor third we would have had and ‘squashes’ it into a diminished third, and with the following B, it ‘squashes’ a perfect fifth into a diminished fifth” (“John Williams Themes” par. 14).

Identical intervals occur near the end of the part “A.” They can be seen in bars #13-15; on the other hand, an additional tone appears in this case (see Fig. 3). These weird intervals encountered in both phrases imbue the theme with the ability to cause the feeling of magic and wonder.

Inception

Inception is a science fiction movie directed by Christopher Nolan. The music to this 2010 film was written by Hans Zimmer. Background music is played almost constantly in the film, letting the viewers continuously experience a flow of strong feelings and emotions.

It is interesting that there are not many themes or motifs in the movie, but there are many rhythms, as well as ambient sounds (Broxton par. 4). One of the rhythmic elements is a simple iambic rhythm; it occurs in a number of tracks. It can be heard, for instance, in the song named “Half-Remembered Dream,” which is then followed by “We Built Our Own World.” It is highlighted that the composer took this rhythm from the famous Edith Piaf’s song, “Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien” (which can also be heard throughout the movie as a diegetic sound utilized by Cobb and his team of “extractors”), and changed it by drastically slowing it down to transform it into “something large and imposing” (“The perfect movie soundtrack” par. 2).

This rhythm is also employed by the composer in a series of paired string chords. It is pointed out that “the languor of the strings simultaneously suggests both melancholy and a hazy sense of time passing, fitting considering the film’s emphasis on concentric dream-states” (“The perfect movie soundtrack” par. 3). It is worth noting that, after the songs “Half-Remembered Dream” and “We Built Our Own World” end, they are immediately followed by the “Dream Is Collapsing” song, which utilizes another motif. This composition employs a recurrent chord progression: firstly, G minor – F# major; then, E flat major – B major; and, finally, it seesaws between G and F#. It is stressed that “this intimate opening becomes the minimalistic backdrop for a huge orchestral crescendo, culminating in a fortissimo climax that unites this chord sequence with the principal idea, the iambic rhythm” (“The perfect movie soundtrack” par. 3).

It should be highlighted that virtually every scene in the movie includes some type of musical accompaniment, which imbues even the simplest actions with “an ‘epic’ feel,” making the emotions of the viewers rich and profound (“Hans Zimmer – Inception Music Analysis” par. 4).

Interstellar

Interstellar (2014) is another science fiction movie directed by Nolan. The film was nominated for Oscar in 2015 (“Oscar Nominees 2015” par. 1). The music for the movie was also written by Zimmer. The composer utilizes a pipe organ while playing non-diegetic music to create certain associations with religion or, rather, with certain aspects of existence that religion is commonly perceived to deal with. The movie is not religious, though. It creates the feeling of greatness and immensity of the universe, and characters of the movie strive towards this greatness, thus transcending the level of ordinary existence (hence the analogy with religion) (“Oscar Nominees 2015” par. 2-4).

The music used in Interstellar skillfully connects the various topics employed in the movie, namely, the ones of familial love (between Cooper and his daughter Murph) and intense action, utilizing a single theme for both topics, indicating the connection between the two; the topic of wonder (which is represented by a separate theme); and the topic of striving for control and achieving it (another separate theme) (“Oscar Nominees 2015” par. 23).

This theme of wonder is connected to the exciting and ambitious concepts of interstellar travel utilizing wormholes, the discovery of exoplanets, and colonization of distant stellar systems; it expresses the feeling of fascination with the enchanting universe. It appears in the movie a few times, for instance, when Cooper and his team first come aboard onto their spaceship of Endurance, when they travel via the wormhole, and when Cooper and Mann investigate one of the exoplanets.

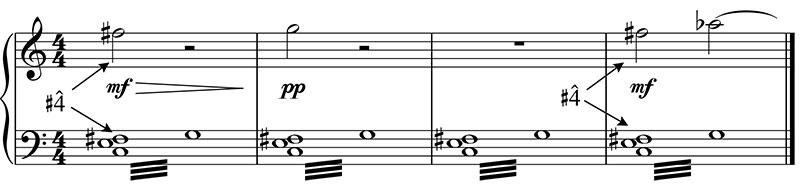

One of the most noticeable characteristics of this theme is its continuing accompaniment, as well as constant repetition of the same melodic pitch (see Fig. 4). It is highlighted that this accompaniment maintains a chord with a “dissonance created by the raised 4 of the scale” (“Oscar Nominees 2015” par. 18). This very scale degree is often used to induce emotions connected to the enigmatic, magnificent, and incomprehensible (“Oscar Nominees 2015” par. 18).

Conclusion

Music is not only an independent type of art; it also often serves as an accompaniment to many other kinds of work. Nowadays, every movie incorporates music as its integral part. The functions that music performs in films are many; they include attracting and directing the viewer’s attention, influencing their mood, communicating psychological aspects of the story, showing the pace of on-screen events, etc. For instance, in Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, the “Hedwig’s Theme” provides the viewers with the feeling that benevolent, fairytale magic awaits them in the movie. In Inception, the composer employs music to constantly keep the viewers on the edge of their seat, to communicate the feeling of danger or excitement.

Finally, the Wonder Theme in Interstellar expresses the feeling of awe and fascination with the magnificence and immensity of the universe. The music in movies effectively utilizes the way the human brain processes and interprets sounds, making cinematography much more exciting and colorful, and communicating some aspects which would otherwise be very difficult to express. It can be argued that without any music, the art of cinematography could be considered crippled.

Works Cited

Broxton, Jonathan. Inception – Hans Zimmer. 2010. Web.

Diegetic Music, Non-Diegetic Music, and ‘Source Scoring’. 2013. Web.

Hans Zimmer – Inception Music Analysis. 2013. Web.

John Williams Themes, Part 6 of 6: Hedwig’s Theme from Harry Potter. 2013. Web.

Oscar Nominees 2015, Best Original Score (Part 5 of 6): Hans Zimmer’s Interstellar. 2015. Web.

The perfect movie soundtrack: Hans Zimmer – Inception. 2010. Web.

Webster, Jamie Lynn 2009, The Music of Harry Potter: Continuity and Change in the First Five Films. Web.