The Small Lot Ordinance policy was introduced in 2005; its aim was to present affordable housing opportunities for families with low and medium income. This paper aims to analyze the background, the content, and the successfulness of the policy.

The Past

The affordable housing crisis began in the 1990s, and was the cause of shortfall of 300.000 units; Los Angeles area was the second most overcrowded in the United States (Whittemore, 2012). Moreover, in 2001 15% of the households in the Los Angeles area were overcrowded. The number of affordable housing units that was built each year was 8.000; however, the city needed 60.000 units to overcome the crisis and provide affordable units to the citizens.

Background and Initial Problems

Due to the crisis, the cost of housing was extremely high. Low wage service workers were forced to move to other suburban areas, as they could not afford the units that the market offered them: a two-bedroom apartment cost 766$ per month, and a minimum wage worker needed to work 100 hours per week to cover the rent expenses (Los Angeles city council’s, 2000). As the report of the crisis task force had stated, thousands of units would be demolished so that residential and school construction units could take their place. However, such means would only increase the rent and make the remaining units unaffordable for low wage workers and families with low income.

This crisis made the housing units unaffordable not only for low-income families but also for those with the median income as well. As the Task Force had noticed, the houses were mostly affordable only for the families with high income, while the others had to move to other areas in search for cheaper rent (Los Angeles city council’s, 2000). Between 1998 and 1999, only 1.940 new housing units were built, while the population of the area had increased by 65.000 people (Los Angeles city council’s, 2000). Some argued that the city designed such plans that were no longer relevant, as the problem with the shortage of the land was ignored by the authorities (Whittemore, 2012). Thus, the number of overcrowded units continued to grow. By 1990, there were more than 40.000 illegal dwelling units in the area (Whittemore, 2012). Although a joint task force advised rehabilitating the units, many homeowners refused to accept this measure as a suitable one. Thus, the problem remained unresolved.

How the Problems Were Measured

Los Angeles has implemented various strategies and sub-strategies to defeat high cost of the housing units and high density of the areas: infill development, smart growth, affordable housing, and, of course, small lot developments. The problems with the infill development were discussed by Steinacker (2003) who stressed their diseconomies of scale and time- and money-consuming rezoning of the city. As some of these land parcels were previously in industrial use, they were obviously not able to provide a healthy environment for future residents. Infill development is expected to attract middle to high-income families; however, it is not always possible, at least due to environmental hazards that the land parcels may present (Steinacker, 2003).

Moreover, such housing units are definitely not “affordable” and therefore are not available for families with low income. Smart growth focuses on the suburbs as they can provide more space for city workers but are cheaper than apartments and houses in the city. However, most of the units available for rent in the suburban areas are single-family houses; thus, those who seek multifamily houses are forced to rent units in the city where the price can make up the half of their monthly income (Steinacker, 2003). Apparently, infill development is only then profitable and reasonable, when it is implemented in the areas with the strong housing market where the population is constantly growing (Steinacker, 2003). When the small lot developments were suggested, it was still unclear whether they would be affordable for middle- and low-income families, which was their initial aim.

In 1994, it was reported that the city could provide 1,210,819 existing units and additional 958,237 units in the nearest future (Whittemore, 2012). Thus, the authorities had stated, it was a 100% build-out. Nevertheless, in the next 15 years, only 84,255 multi-family units were added (approx. 14% of the estimated build-out), while the added 21,888 single-family units covered “65% of the single-family build-out” (Whittemore, 2012, p. 406). Thus, the extreme demand for multi-family houses was not met. The outcomes of the policy will be discussed in detail in the corresponding section.

Policy Development

In 2005, the amendment titled as the Small Lot Subdivision (Townhome) Ordinance was adopted by the City Council of Los Angeles. The small units allowed the purchasers become the owners both of the land and the structure; compared to condominium projects, this approach was more profitable as the buyers had more than a percentage of the shared space.

The definition of the lots needed to be specified to ensure that all requirements provided in the ordinance were followed. Per se, the housing lots were detached townhouses that provided the buyer with the ownership both of the structure and the land. In order to avoid problems with the city laws regarding housing units, these small lot developments had other standards that the developers could use. For example, the lots were not provided with parking spaces, but two garaged parking lots were still required for each unit (Los Angeles, California: Small Lot Ordinance, 2011).

The stakeholders of the policy are the low and middle-income families, as well as recent college graduates, low-wage workers, minimum wage workers, workers with the median wage who are struggling to acquire affordable housing units in Los Angeles. As Whittemore (2012) states, the population of the city continues to grow, and low-income areas have finally received the authorities’ attention; nevertheless, although the plan seems suitable at first, Whittemore (2012) argues that it has not provided any positive impact on the housing crisis. Nevertheless, the advantage of this ordinance is the involvement of the interest groups, although not direct. The problem of the unaffordable housing units and rent has created serious anxieties among the low-income residents of the illegal or soon-to-be-demolished units, thus providing the needed impact on the City Council.

If we look at the interest groups more generally, we can divide them into two separate groups with different agendas: the first one (namely the families with median and low income) are claiming that the solution to the problem would be affordable and/or public housing controlled by the government and implemented by private developers (Steinacker, 2003); the second one assumed that smart growth would be more suitable for improving housing and living conditions in the areas with high density. However, as it was discussed above, smart growth is a strategy that focuses mostly on housing units available for high-income families. Nevertheless, small lot developments can be viewed as a subtype of smart growth, which aim is not to increase the number of housing units but to make these units more affordable (Steinacker, 2003). Thus, small lot developments were supposed to be a solution that both groups would find satisfactory.

The definition of the lot, as well as other design guidelines, were presented in the original ordinance that was approved on December 16, 2004. A lot, according to the original ordinance, is “a parcel of land occupied or to be occupied by a use, building, or a unit group” (Ordinance no. 176354, 2005). Yards and open spaces are also the parts of the lot. The use was prohibited from extending “more than 65 feet from the boundary of the less restrictive zone which it adjoins” (Ordinance no. 176354, 2005). The minimum lot width is stated to be 16 feet, while the minimum area lot is 600 square feet (Ordinance no. 176354, 2005). While some concerns were expressed about the efficacy of such measures, no other resolutions of the affordability of the housing units were provided (Whittemore, 2012). The advantage of the policy is that it does not order to create new units but rather uses underutilized lots to provide new housing units for residents. Thus, the policy was initially implemented in the form of an ordinance or a local law passed by the municipal authorities of the city. The ordinance was passed on 14 December 2004 and approved on 16 December of the same year. It consisted of seven sections where the design of small lot developments, as well as all requirements and restrictions, were prescribed. It was and still is a matter of the local (municipal) jurisdiction, as it concerns the issues of the Los Angeles County, but not the whole state (California).

The Present

Existing Policy Context

The Small Lot Design Guidelines were revised in 2015; Advisory Agency Policy and the Guidelines attached to it were to replace the original Advisory Policy and Guidelines presented in 2006. These guidelines were only applicable to the subjects that were regulated by the Small Lot Ordinance. As it was stated in the revised policy, the first ordinance did not explicitly prohibit “commercial uses as parts of small lot subdivision” (Revised small lot design guidelines, 2015). Therefore, the revised version suggests that mixed-use buildings’ establishment should be allowed as well. In these buildings, the ground floor is expected to be of commercial use, while the residence will be located on the upper level of the building (Revised small lot design guidelines, 2015).

As the initial and the revised versions of the ordinance were designed to align with the General Plan Framework of Los Angeles, the requirements for the design of small lot developments that are located along commercial corridors need to “define the character of the proposed development” (Revised small lot design guidelines, 2015). The authors of the guidelines also notice that although small lot developments are an alternative to suburban single-family houses and can reduce density and provide easier homeownership, the proximity of the lots to each other have brought additional challenges and “require… considerations about massing, height, and transitional areas…” (Revised small lot design guidelines, 2015, p. 10). From this statement, it can be concluded that the policy has provided a solution to the problem connected to the lack of single-family houses in the city area and their unaffordability but created additional challenges in the architectural design of the residential projects.

The significance of the newer guidelines is their detailed approach to the relations between the small lots and the streets. No detailed requirements or advice were presented in the first ordinance; thus, small lot developments were constructed and designed without any regard to the streets and neighborhoods. The aim of the guidelines was to present possible configurations of the small lot developments so that they are compatible with the neighborhoods. Some of the suggestions include maximization of green space, utilization of alleyways for vehicular access, and improvement of pedestrian circulation (Revised small lot design guidelines, 2015). It may seem at first that the policy’s implementation was successful, and the challenges that arose due to the building of the small lot developments are not directly linked to any deterioration of the living conditions in the units.

Was the Policy Successful?

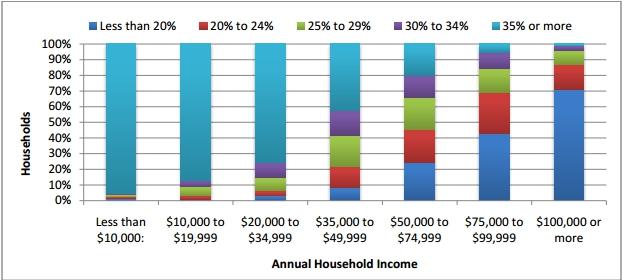

Nevertheless, the policy is not as successful as it might appear. It has not followed its initial aim, affordable pricing, as the rent is still extremely high in the neighborhoods that are regulated by the ordinance. As the areas began to change according to the requirements of the small lot development, low-income and low-wage families were not able to afford the rent, they moved out, and families with higher income have taken their place (Scheinbaum, 2015). Some believe that the small lot developments do not only ruin the character of the neighborhoods but also lead to mansionization of the areas (Scheinbaum, 2015). Thirty-seven small lot developments were approved in 2014. Although their aim was to provide affordable housing stock and decrease the cost of the rent, new houses were often too expensive to be rented by families with low and median income (Scheinbaum, 2015). The ordinance was approved in 2005; the data from 2010 shows that families with low income still had to spend a significant amount of their income on the rent (see Fig.1):

Approximately more than 2.000 new homes were built on the small development lots after the ordinance was passed in 2005; however, some of them are rented in neighborhoods for families with high income such as Echo Park or Silver Lake, contrary to the statement that the small lot developments’ advantage is their affordability (Scheinbaum, 2015). The homeownership rate in Los Angeles County one of the lowest across the USA, as the pricing is too high, and citizens are only able to rent houses and not buy them. The Small Lot Ordinance was supposed to be a solution to this problem, providing affordable housing that could be owned and was operated by other rules compared to condominiums and single-family homes. However, as Scheinbaum (2015) states, small lots’ cost is normally between $500,000 and $850,000, while single-family homes cost approximately $526,000 in Los Angeles (para. 8). Thus, small lot developments are not as affordable as they were indented to be and do not resolve the problem of housing stock affordability because they can cost more than single family houses that are also not considered affordable.

Another problem that was addressed by the Department of City Planning and suggested to be corrected in the Department’s report is the procedural inefficiency of the recordation of the final map. According to the report, as building permission could not be issued until the map was recorded, the applicants had to either wait for the recordation which was risky or to file for deviations of the lot (Department of City Planning, 2014). Both of these procedures were considered inefficient; it was suggested that the applicants are to receive building permit prior to the final recordation of the map so that they are not forced to wait up to two years to begin construction (Department of City Planning, 2014). It remains unmentioned why the problem was not addressed earlier, and the report does not mention the losses that were caused by this procedure. However, it is clear that the original ordinance did not address the problem. As it will be seen in the recommendations section, the original ordinance missed particular possible problems and issues that contributed to the failure of the policy.

The policy was updated in 2016, and additional changes were introduced to the original ordinance, e.g. new design and map standards so that the previous Design Guidelines could be refined (Department of City Planning, 2016). In general, the code amendment presented various modifications of the previous guidelines; these changes focused on the problems of density and design, as well as other restrictions that the small lot developments had to face. The new, detailed guidelines will be available to the public in January 2017. It is possible that the new update of the policy will fill the gaps in the previous versions of it.

So far, the costs of the policy do outweigh the benefits, as the policy did not provide affordable housing stock to the L.A. market. Although not provided in the official reports from the City Council, the comparison of the small lot developments to the L.A. housing stock proves that the small lots were affordable in some years, but not all: in 2007, price per square foot was $426.66 (housing stock) vs. $281.81 (small lot developments), while in 2013, 2014, and 2015 the pricing was $326.28 vs. $376.96, 365.16 vs. 472.49, and $384.75 vs. $484.55 respectively (Zillow, 2016). Thus, the Small Lot Ordinance policy did not resolve both the problem of density and the problem of housing affordability.

The Future

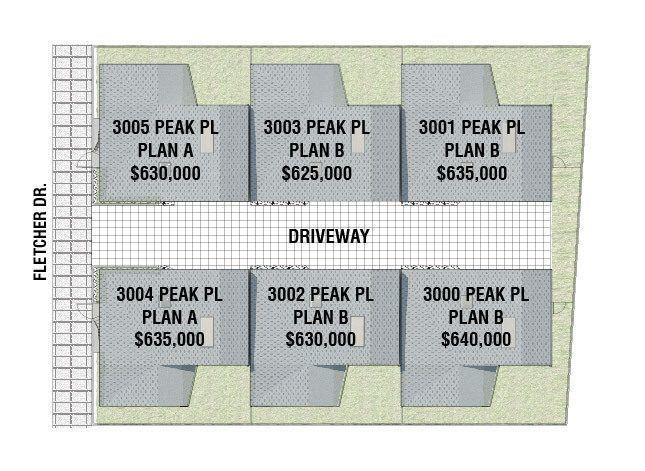

As the policy was not successful in resolving the issue of affordability on the Los Angeles market, appropriate recommendations need to be articulated to understand how the policymakers should proceed with it. To provide successful outcomes, the City needs to provide better control of the constructions of small lot developments and ensure that the units provided by developers are suitable for families with low and medium income. The new design guidelines that will be published online in 2017 will possibly help the policymakers resolve the problem of density as well. So far, the Department of City Planning mostly addressed the design and lack of open spaces on the small lot development units. However, the homes on the units provided for sale or rent are often luxurious and costly; they do not provide opportunities for first-time house buyers but rather target the potential purchasers from the upper class. The following photos depict units which cost is estimated to be between $600.000 and $1.3 billion dollars (see Fig.3, 4, 5).

As it can be seen from the pictures, the facilities located on the units are not regulated by certain rules that would help the houses relate to the street or neighborhood they are located in. It is advisable to develop a set of rules that would cover the problem in detail; as for now, the units can vary so significantly that it is impossible to reach any integrity. This recommendation, as well as the others expressed above, are politically feasible because they address the issues that the policy overlooked; these issues were the reason why it was so heavily criticized and marked as controversial. The current cost of the units suggests that certain neighborhoods are built only for the members of the upper class, which violates the initial aim of the ordinance. New design plan might prescribe new rules about the size of the small lot developments, reducing their cost and integrating them into the neighborhoods.

Affordability per se is not regulated by any developers or rules; in fact, none of the documents dedicated to the small lot developments defines affordability and quantifies it. In order to make the definition clearer both for developers and for future purchasers or renters, it is possible to define affordability (e.g. the cost of an affordable house will be 30% lower than the cost of an average house in the unit). It also seems reasonable to suggest constructing affordable units that will provide homes with a lower price compared to the Los Angeles market. After all, such units will align with the original aim of the ordinance and at least partially solve the problem of expensive rents for low- and middle-class representatives.

Expanding rent control and public housing also seem to be solutions that the Department of City Planning could find effective. Rent control would help decrease the number of situations where families with low income are not able to rent a house that is labeled as affordable. It is an effective measure that can contribute to the existing affordable housing policies and make them more efficient.

Unless small lot developments are indeed made affordable, public housing often remains the only option for citizens with financially unstable income. Although public housing is often associated with poor conditions and high crime rates, it is still possible to use it as a tool that will resolve the problem of lacking housing opportunities. Moreover, public housing is a policy that also needs to be revised and implemented accordingly to the demands of citizens. Combined, public housing and small lot developments have the potential to improve the housing crisis in the city of Los Angeles significantly.

Another option that is often regarded as an alternative or an addition to small development units is micro-housing. Micro-housing allows the construction of small houses that do not increase density and are affordable for single citizens or small families. Micro-housing can become a part of small lot developments policy, presenting yet another opportunity for affordable housing.

The transition from the status quo to proposed recommendations is not challenging, as most of them are easy to include into the updates of the policy; moreover, some of the policies proposed here already exist and simply need to be revised. It should not be forgotten that the new guidelines that will be released in 2017 might provide a solution to the discussed problems.

References

Department of City Planning. (2014). Department of City Planning recommendation report. Web.

Department of City Planning. (2016). Small Lot Subdivision: Code amendment and policy update. Frequently asked questions. Web.

Los Angeles city council’s affordable housing crisis task force offers bold recommendations.(2000). Web.

Los Angeles, California: Small Lot Ordinance. (2011). Web.

Ordinance no. 176354. (2005). Web.

Revised small lot design guidelines. (2015). Web.

Scheinbaum, C. (2015). L.A.’s small lot homes: Destroying low-rent housing, restoring the American dream, or both? Web.

Steinacker, A. (2003). Infill development and affordable housing patterns from 1996 to 2000. Urban affairs review, 38(4), 492-509.

Whittemore, A. H. (2012). Zoning Los Angeles: a brief history of four regimes. Planning Perspectives, 27(3), 393-415.

Zillow. (2016). Los Angeles CA Home Prices & Home Values. Web.