Introduction

The study was on the topic of overcoming the church’s hurt. The research employed a survey technique in which individuals were subjected to an open interview of 12 research questions to establish the nature of church hurt and its impacts on the victims. The participants of the study were former victims who were randomly picked. The thematic analysis will apply the Braun and Clarke technique to assess and present the results of the study. The Braun and Clark thematic analysis will apply semantic versus latent coding techniques to generate codes and identify themes.

Assumptions

From the assessment, it is evident that the participants did not confine themselves in their responses but rather gave a comprehensive insight into the subject (Terry & Nikki, 2020). As a result, the study provides the opportunity to go beyond the descriptive level of the participant as well as analyze the data.

Coding

The thematic analysis uses both semantic and latent approaches to generate coding. The analysis will assess all the interview questions and answers to generate the initial codes. Since different individuals participated in the study, all the responses will be analyzed in their descriptive state (Byrne, 2022). In addition, the latent approach will enable the identification of the hidden meanings and make some assumptions that might have been ignored by the participants.

Familiarizing with the Data

To familiarize myself with the data for thematic analysis, the interview responses were insightful read, and assessed. Since the interview was done with individual participants, the feedback was analyzed in a particular manner to get the thoughts and experiences of every participant (Braun, Victoria, and Nikki, 2022). A total of 12 interview feedbacks were analyzed in order to obtain the view of each participant concerning the topic study.

Most participants percept church hurt as pain within a religious institution. As reported by the participants, church hurt is defined as the pain inflicted on a believer by a fellow believer, religious leader, or members within the same church setting or different but under the same religious umbrella (Braun et al., 2023). In the same vein, the examples given by the participants included gossip and discrimination. C1

Most of the victims’ painful experiences stemmed from fellow church members. The majority stated that their distress was caused by individuals they trusted within the church. Going through the interview responses, the participants expressed disappointment as they had not anticipated undergoing such experiences (Kua, Winnie, and Wee, 2022). Since church members are united by the body of Christ, they live as a family and thus have expectations from the church.C2

Church hurt negatively impacted victims’ involvement in religious ministry in terms of attendance and member relationships. Since the church hurt has a psychological effect, most of the individuals who have undergone the ordeal are left with emotional torture, which in turn lowers their motivation in the religious setting (Braun & Victoria, 2019). From most confessions, the victims withdrew their interest in church activities. C3

Most of the victims of church hurt do not share their experiences with their fellows or religious leaders but choose to suffer in silence. Even though some shared their experiences with other church members and leaders, they did not get the needed intervention (Trainor & Andrea, 2021). The victims were not satisfied with the intervention by the people they shared their problems with, as most did not help or intervene. C4

The victims recommend support as an optimal way to address church hurt. The people feel the church community is doing little to resolve the menace or giving it a wised berth. Even though some victims shared their experiences with other members and leaders, they felt the group did little to help them or resolve problems (Braun & Victoria, 2023). For example, the affected individuals expected the church leadership to listen to their stories and follow up on the cases. C5

Codes

- (C1) Church hurt is pain within the church.

- (C2) Church hurt originates from within the church setting

- (C3) Church hurt affects religious participation

- (C4) Victims of church hurt suffer in silence

- (C5) Support is the appropriate solution

Themes

Key

Defining and naming the Themes

Themes

The definition of church hurt

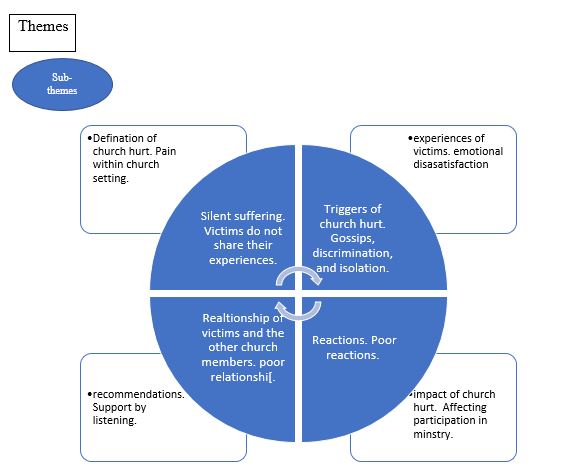

As seen in Figure 1.1, most participants view church hurt in the context of pain within a religious setting. Participants describe church hurt as the emotional distress caused by fellow believers, religious leaders, or members within the same or related religious communities (Braun et al., 2023). Similarly, the examples provided by the participants, such as gossip, outcast, and discrimination, are associated with the church setting

Experiences of victims

As depicted in Figure 1.1, most of the victims’ experiences were from fellow members. According to the majority, their hurting or rather painful experiences were contributed by the people they trusted, such as religious leaders, fellow believers, and church members in general. The interview responses showed that the participants felt disappointed because they had not expected the experience. Most experiences were emotional and affected the psychological well-being of the victims.

The impact of church hurt

As illustrated in Figure 1.1, church hurt affected the participation of victims in the religious ministry. Going through the interviews, most victims were affected by the experiences which lowered their participation in religious activities. For example, there was lower morale in church attendance. Since the church hurt has a psychological effect, the victims are left emotionally distressed, which subsequently diminished their motivation within the religious setting.

Recommendations

As demonstrated in Figure 1.1, the victims recommend support as the major resolution for church hurt. The individuals believe the church community should listen to their stories and intervene; however, they perceive the group as making minimal efforts to address the issue or intentionally avoiding it (Janis, 2022). Although some victims shared their experiences with members and leaders, they felt that the group did little to assist them or resolve their concerns.

Sub-Themes

The triggers

As shown in Figure 1.1, the participants mentioned some of the actions, such as gossip, isolation, and discrimination, as the major triggers of the church hurt. According to their confessions, some church members subjected them to discrimination and isolation, making them feel like outcasts in the church setting (Campbell et al., 2021). In other instances, the participants cited gossip and discrimination by fellow believers as the cause of their hurting.

Relationships

As illustrated in Figure 1.1, church hurt destroys the relationships between the victims and the perpetrators. According to participants, they never felt the same love and sense of belonging that they enjoyed after the hurting. For some victims, they started viewing their fellow believers and leaders in a different way. Most participants believe the experience can destroy not only the church relationship but the entire association of the body of Christ.

Reactions

As demonstrated in Figure 1.1, the participants hinted at poor reactions from the victims and the other members. According to their confessions, the hurt was not something they expected since they believed the church was the place where they could find peace and solace. In addition, since they are united under the body of Christ, they did not expect their fellow members to isolate and discriminate against them.

Silent Suffering

As illustrated in Figure 1.1, many individuals who experience church hurt choose not to disclose their struggles to fellow believers or religious leaders, opting instead to endure their pain in silence. While some did confide in other members or leaders, they did not receive the necessary support or intervention. As a result, most participants confessed to suffering in silence instead of telling other members or leaders about their experiences.

Reporting Findings

The report shows that church hurt is the pain inflicted on believers within the religious setting by the actions of other members, such as isolation, discrimination, and gossip. Church hurt has various impacts on the victims, including affecting their participation in the ministry and their general relationship within the church setting (Braun & Victoria, 2021). Most victims recommend support by listening and intervention as the appropriate solution to the problem.

Conclusion

In summary, the Braun and Clark thematic analysis used data from the study on the topic of church hurting, where victims gave their experiences and knowledge on the subject. The study used an interview report from a survey study that was done on 12 participants who were subjected to 12 different research questions on the topic. The Braun and Clark thematic analysis employed semantic and latent techniques to familiarize with the data, generate codes, and single out the themes.

References

Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2019. “Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis.” Qualitative research in sport, exercise and health 11, no. 4: 589-597. Web.

Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2021. “Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing Reflexive Thematic Analysis and other Pattern‐Based Qualitative Analytic Approaches.” Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 21, no. 1: 37-47. Web.

Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2022. “Conceptual and Design Thinking for Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Psychology 9, no. 1: 3. Web.

Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2023. “Toward Good Practice in Thematic Analysis: Avoiding Common Problems and becoming a Knowing Researcher.” International Journal of Transgender Health 24, no. 1: 1-6. Web.

Braun, Virginia, Victoria Clarke, and Nikki Hayfield. 2022. “‘A Starting Point for Your Journey, Not a Map’: Nikki Hayfield in Conversation with Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke about Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 19, no. 2: 424-445. Web.

Braun, Virginia, Victoria Clarke, Nikki Hayfield, Louise Davey, and Elizabeth Jenkinson. 2023. “Doing Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Supporting Research in Counselling and Psychotherapy: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Research, pp. 19-38. Cham: Springer International Publishing. Web.

Byrne, David. 2022. “A Worked Example of Braun and Clarke’s Approach to Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Quality & Quantity 56, no. 3: 1391-1412. Web.

Campbell, Karen A., Elizabeth Orr, Pamela Durepos, Linda Nguyen, Lin Li, Carly Whitmore, Paige Gehrke, Leslie Graham, and Susan M. Jack. 2021. “Reflexive Thematic Analysis for Applied Qualitative Health Research.” The Qualitative Report 26, no. 6: 2011-2028. Web.

Janis, Ilyana. 2022. “Strategies for Establishing Dependability between Two Qualitative Intrinsic Case Studies: A Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Field Methods 34, no. 3: 240-255. Web.

Kua, Joanne, Winnie Teo, and Wee Shiong Lim. 2022. “Learning Experiences of Adaptive Experts: A Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Advances in Health Sciences Education 27, no. 5: 1345-1359. Web.

Terry, Gareth, and Nikki Hayfield. 2020. “Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Handbook of qualitative research in education, pp. 430-441. Edward Elgar Publishing. Web.

Trainor, Lisa R., and Andrea Bundon. 2021. “Developing the Craft: Reflexive Accounts of Doing Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 13, no. 5: 705-726. Web.