The aim of this study has been to examine the prevalence and impact of unbalanced working hours to reward ratio in the hotel sector. To meet this research aim, three objectives were developed. The first one was designed to understand the relationship between working hours and financial compensation received by employees in the hotel sector and the second one aimed at identifying the influence of unbalanced working hours to reward ratio on employees’ perceptions of organizational justice. The third one was to estimate the prevalence of unbalanced working hours to rewards ratio in the hotel sector. Using a quantitative research approach and collecting data from 112 respondents in a survey, the findings revealed that there was no relationship between working hours and financial compensation. Additionally, the researcher did not find evidence indicating that the influence of unbalanced working hours to reward ratio influenced employees’ perceptions of organizational justice. Furthermore, the evidence gathered in the study indicated that wage differentials were not widespread. These findings are inconsistent with the extant literature, which suggests a correlation between working hours and financial compensation.

Introduction

Maintaining an active and energized workforce is one of the most important roles of management. However, for most organizations, this is a daunting task because existing motivation strategies pose different results based on the industry involved. The hotel sector is one of the most significant tenets of the global economy because it employs millions of people around the world (Brotherton, 2015). Characterized by different players in the sector, their varying scope, nature, and size have forced them to adopt different rewards strategies to motivate employees. Therefore, paying attention to the efficacy of these strategies in bolstering workplace performance is important for the hotel industry because it is largely a service-oriented sector, and performance is based on employee motivation (Rosemberg & Li, 2018). This statement implies that quality is a key performance indicator for the sector owing to its importance in improving customer experience. Based on the need to provide high-quality services to customers, the importance of understanding the efficacy of employee reward strategies is of critical importance to the industry.

Different organizations motivate their employees using unique and adaptable ways to improve productivity. However, financial motivation outweighs other alternative strategies adopted by managers to energize their employees to improve their productivity. This type of HRM strategy is based on the assumption that employees would perform better if they get increased financial rewards (Boella & Goss-Turner, 2020). Therefore, the entire reward system is pegged on the provision of monetary gains for good performance. These kinds of rewards primarily involve money, but they may also include other aspects of its use, such as bonuses, commissions, and fringe benefits. Relative to this assertion, research studies have shown that financial rewards are directly correlated with improved levels of job satisfaction and security (Boella & Goss-Turner, 2020). Additional evidence suggests that better financial remuneration is associated with low levels of employee turnover and better recruitment opportunities (Tanwar & Prasad, 2016). These benefits are linked to enhanced organizational success because managers can retain knowledge and experience by having a motivated workforce. Consequently, such organizations allow their employees to become more stable in their work as they familiarize themselves with it because of staying with the company for a long time. Additional research evidence suggests that employees who earn enough money to cover their basic expenses and save for the future are unlikely to serve notice to their employers to vacate their positions because they will be contented with their work (Rosemberg & Li, 2018). This way, they are likely to save themselves the hassle of looking for a new job. Similarly, their employers save the time and resources needed to look for a replacement.

The aforementioned advantages that are linked to improved employee performance stem from the understanding that financial rewards signal to employees that their employers care about their wellbeing. Money is also a recognition of the value of work they put in their respective fields of operation. The association between these positive aspects of employee perception and work output has been linked with the view that money is a driver of employee performance and organizational change (Boella & Goss-Turner, 2020). Stated differently, the more a business makes revenue, the higher the chances that its employees will improve their performance. Therefore, those who feel valued work harder than their counterparts who do not expect any financial benefits because they believe that their work would ultimately create conditions for the improvement of the company’s overall financial situation.

The concept of organizational justice emerges from the above analysis within the context of how employees perceive compensation policies adopted by an organization as being either morally, ethically, or legally right. Broadly, this idea has been used to explain perceptions of fair pay, equal opportunities for promotion, and employee recruitment processes. The concept of organizational justice will be extensively mentioned in this paper to mean perceptions of fairness regarding a company’s reward policies. This concept is often compared to corporate social responsibility, which refers to how firms interact with their external partners (Lee, Kim, Son, & Kim, 2015). Therefore, in the context of this study, organizational justice will refer to how companies treat their internal partners – employees. In this assessment, employees make judgments about how their superiors should treat them based on how they are compensated for their work. These perceptions ordinarily result in attitude and behavioral changes among employees, which may ultimately affect organizational performance.

Rationale of Study

Financial motivation is an important determinant of employee productivity. However, significant wage discrepancies between high-ranking employees, such as managers and supervisors, and low-skilled workers have made it difficult to operate optimally. These wage gap discrepancies emerge in different ways. For example, there is a significant income disparity between employees in developed and developing countries because workers in the latter group could out-earn their counterparts in developing nations several times over (Artazcoz et al., 2016). Wage discrepancies have also emerged among genders, as women tend to earn lower wages compared to their male counterparts in several job groups. For example, researchers estimate that women in the hotel industry earn about 18% less than their male counterparts do (Witts, 2015). The pay divide gap is also evident in several other demographic groups, such as among older and younger employees, as well as across industries because they represent the same pattern of wage earnings.

Although pay gap inequalities continue to persist in many economic sectors, its effects on companies that operate in the hotel industry may be more extensive and impactful because of the important role that services play in contributing to customer satisfaction. Research studies suggest that the industry is in the top ten list for promoting wage gap inequalities (Brotherton, 2015). Typically, low wages, low levels of educational attainment, and high employee turnover characterize the employment and labor environment in the hotel industry (Joo-Ee, 2016). Ironically, employees who are the least paid also get to interact with customers more than their superiors do, thereby creating an opportunity for customers to feel disgruntled from poor services that originate from underpaid workers. Additionally, low-skilled employees spend more working hours in the organization compared to their managers. This statement brings to the fore the need to understand rewards policies relative to the hours employees work in an organization. Relative to this discussion, the following research objectives will be pursued in this study.

The main gap in literature justifying this study is the failure of researchers to link wage gap inequalities and the concept of organizational justice. In this regard, managers have an incomplete picture of the overall effect of their remuneration policies on employee performance because they fail to understand how it is linked to workers’ perceptions of fairness. Consequently, they fail to understand the influences of organizational justice as a subjective phenomenon affecting performance. Similarly, the failure of researchers to link wage gap inequalities and the concept of organizational justice has made it difficult to get a comprehensive view of the effects of employee behaviors and attitudes on a firm’s productivity through their perceptions of fairness and justice. By addressing this gap in the literature, it would be possible to have a broader understanding of the main factors influencing performance at individual and group levels, based on their perceptions of organizational justice.

Aim

This study aims to examine the prevalence and impact of unbalanced working hours to rewards ratio in the hotel sector. This research aim is linked to the research problem, which highlights wage inequalities in the industry.

Objectives

Stemming from the research aim described above, three objectives will guide this study and they are outlined below.

- To estimate the prevalence of unbalanced working hours to rewards ratio in the hotel sector

- To quantify the relationship between unbalanced ratio of working hours to rewards ratio in the hotel sector

- To measure the effects of unbalanced working hours to reward ratio on employees’ perceptions of organizational justice in the hotel sector

Literature Review

This chapter contains an evaluation of existing literature addressing the research topic. To recap, this investigation aims to examine the prevalence and impact of unbalanced working hours to reward ratio in the hotel sector. To address the scope of this statement, three objectives will be pursued. The first one is to understand the relationship between working hours and financial compensation received by employees in the hotel sector. The second one is to identify the influence of unbalanced working hours to reward ratio on employees’ perceptions of organizational justice and the third one is to estimate the prevalence of unbalanced working hours to rewards ratio in the hotel sector. At the end of this chapter, the researcher will highlight the conceptual framework for conducting this investigation and interrogate existing literature on the research topic.

Rewards in the Hotel Sector

Reward policies adopted in the hotel sector continue to highlight wage inequalities that exist in the industry. Several research studies have been conducted to address this problem. For example, Casado-Díaz and Simón (2016) did a study in Spain, which is a leading hotel sector in Europe, and found that wage gap inequalities in the market disproportionately affected low-skilled workers and those who have lower education levels. Therefore, employees who have low skills, education qualifications, and experience generally occupy low-ranking positions in the sector, which, in turn, attracts lower wages. These findings were obtained after collecting data from a longitudinal study that occurred between 2002 and 2010 (Casado-Díaz & Simón, 2016). Within this period, the researchers found out that workers who suffer from these problems are often dispensable and that is why they rarely get fair compensation for their work.

Additional research studies have tried to draw a link between the low wages of unskilled workers and their poor standards of living. However, a majority of the body of evidence suggests that low wages are inherently linked to low standards of living (Tanwar & Prasad, 2016; Casado-Díaz & Simón, 2016). In other words, the findings suggest that workers are paid low wages because their standards of living are equally low. Conversely, the reverse is also true because it means that those who are paid higher wages benefit from this policy due to their higher standards of living. These findings also suggest that wage differentials could largely be explained by standards of living, but this reason is not sufficient to explain the extent of wage disparities in the hotel industry. This finding further suggests that wage inequalities also exist between workers in the same job category but living in different cities.

Based on the aforementioned statement, employees who live in some of the world’s major capitals are likely to struggle to make a living if they are paid low salaries compared to workers who live in villages or cities that have a low standard of living. These findings mean that wage inequalities vary across different job groups and are likely to be more poignant and impactful to workers in low-level jobs or those who live in areas that have a high cost of living. These categories of workers are also likely to exhibit low performance because of wage inequalities. Overall, these findings were obtained after sampling the views of respondents who were spread across 97 job groups in 67 cities around the world (Sturman et al., 2017). Therefore, the findings highlighted above are comprehensive and could be broadly relied on when making comprehensive rewards policies.

Importance of Working Hours to Rewards Ratio

The relationship between working hours and rewards ratio has largely been ignored in extant literature. However, there has been a big body of evidence explaining the role of rewards on employee performance, burnout, and turnover; with a majority of the research indicating that employees who get paid low wages stand a higher likelihood of performing poorly by providing low-quality service. Nonetheless, the larger debate regarding the importance of working hours to rewards ratio can be best understood by understanding employee wellbeing and their perceptions of organizational justice. The relationship between employee performance, working hours, and rewards ratio has been established in many research studies, including those of Kim et al. (2020), Pradhan and Jena (2017), but the same association has not been effectively addressed in studies that focus on the hotel sector. Indeed, most of the evidence gathered in this area of research has mostly been domiciled in the health or public service sectors. For example, a study by Ryu (2016), which sampled the views of 186 South Koreans investigated the relationship between working hours and age differentials and found out that most employees who clocked many hours at work but got little pay, had a lower sense of wellbeing compared to their counterparts who worked fewer hours and received better pay. This type of employee is likely to suffer from a high sense of dissatisfaction compared to their satisfied counterparts.

Studies that have investigated the same phenomenon in the health sector have come up with similar findings. For example, Roxo et al. (2020) and Nightingale (2019) conducted similar investigations in Europe after sampling the views of 20,000 participants drawn from a mixture of low and high-income countries and found out that most employees who worked long hours and did not receive pay commensurate with their contribution suffered poor health. This situation was found to be true for both male and female employees but was more impactful in countries that respected family values compared to those that had liberal policies. Collectively, these findings support the view that most employees who work long hours and receive low pay have poor well-being. To this end, the quality of their work may be undermined because of low job satisfaction levels. Again, organizational performance is likely to be undermined this way.

Relative to the above assertion, organizational justice affects the relationship between extended working hours and corporate performance by influencing the perception of employees regarding their contribution to an organization. It is particularly relevant to the problem of unfair wage differentials in the hotel sector because it refers to how workers develop their views about fairness in the workplace (Imran et al., 2015). For example, employees who work long hours and do not receive fair pay are likely to perceive a company’s reward system as being unfair. In this characterization of workplace performance, a negative perception of organizational justice is likely to have undesirable connotations on an organization’s brand and performance. Relative to this assertion, Imran et al. (2015) sampled the views of 300 Pakistani workers in the hotel industry and found that negative perceptions of organizational justice have a deleterious impact on productivity. Stated differently, organizations perceived as being unjust experience lower levels of profitability and service delivery compared to those that were mindful of fairness in the workplace.

Similar studies done in Asia have also arrived at the aforementioned conclusion because they affirm the relationship between poor perceptions of organizational justice and performance. Particularly, the concept of distributive justice has influenced how workers see their employers’ compensation policies (Ugaddan & Park, 2019). The main points of reference are perceptions of trust, commitment, and motivation, which are significant to the overall development of the notion of organizational justice. This statement means that an unbalanced relationship between working hours and rewards affected employee commitment, thus decreasing organizational performance.

Efforts-Reward Imbalance

The International Labor Organization (ILO) characterizes the imbalance between employee input and reward as a form of discrimination. Particularly, it identifies low-skilled and uneducated workers as being the most affected (ILO, 2020). It also points out that women are the most affected demographic in both developing and developed nations. Therefore, the imbalance between efforts and rewards means that discrimination is being embedded in the workplace. Mainstream researchers have taken a different approach to study the efforts-rewards imbalance with a vast majority of them suggesting that the unbalanced relationship between working hours and wages is symptomatic of the types of jobs employees choose to do (Shuck et al., 2017). Mainly, their argument is predicated on the understanding that the relationship between efforts and rewards can be explained within conventional tools of economic theory.

Different researchers have further explored the imbalance between efforts and rewards using power relationships that exist among employees and employers. Those who have adopted this line of reasoning argue that the labor market is a neutral force in countering the unbalanced power relationship between the two parties (Prasad, 2019). Therefore, labor-based policies can only act in strengthening or weakening these power relationships but do not fundamentally change the way they work. Additionally, managers who exercise these power relationships act according to traditional norms and procedures governing employee-employer relationships and are generally slow in adopting new ideas to improve employee welfare (Iddagoda & Opatha, 2020). It is in these traditional power relationships that pay differentials exist and have thrived for a long time.

This system of inequality supersedes the normal classification of discriminative policies in the workplace because, typically, an employer bases the traditional metric of defining discriminative practices on the presence of unequal treatment of employee groups. However, in the context of this discussion, the imbalance between working hours and remuneration is systemically embedded in the power relationships between employers and employees. In other words, the traditional forces of employer-employee relationships are, to an extent, implicit in supporting unfair rewards systems because the pay is pegged on value and the current remuneration system is based on traditional notions of value. This statement means that different types of labor have varied perceived value from the employer’s perspective. Thus, possible new conceptions of employee value are ignored in several organizations and by different groups of managers because they rely on traditional power relationships where the employer is always dominant. Therefore, instead of eliminating all forms of bias in an organization’s pay or reward system, the determination of wages is seen as a political and institutional process pegged on traditional conceptions of value.

The traditional imbalance of power between employers and employees contravenes fundamental principles of the ILO, which suggests that human labor should be deemed different from other types of commodities because it is provided by human beings who have feelings and can make their judgments about situations. Therefore, pay should not only be seen as a form of compensation for the value of work provided by workers but also a tool for sustaining livelihoods and families. Additionally, wages offered by managers are not only a basis for compensating employees for their work but also a tool for developing social constructs through which identities are reproduced. This reasoning has birthed the concept of wages as a social practice and it is linked to one of the fundamental principles of this study – organizational justice

Conceptual Framework

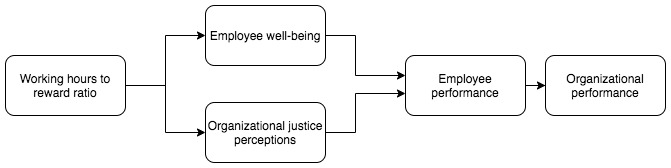

Based on the insights highlighted above, the conceptual framework highlighted in figure 2.1 below explains the modalities and framework for synthesizing the findings of this study. According to the diagram, the relationship between working hours and rewards ratio will be evaluated through an assessment of employee wellbeing and perceptions of organizational justice. These two aspects of performance will be further reviewed to understand employee performance and ultimately organizational output as highlighted below.

Summary

This literature review suggests that the relationship between working hours to rewards ratio is complex and characterized by subjective and context-specific factors that influence how employees construct ideas about organizational justice. However, the findings presented in this section of the paper are anecdotal and not specifically grounded in the hotel industry. At the same time, researchers have made minimal attempts at linking unbalanced working hours, age inequalities and organizational justice. Furthermore, the findings presented by other researchers regarding employee remuneration are too broad to make any sensible conclusions about the relationship between working hours, fair compensation, and organizational justice. Additionally, the evidence espoused in this report is not sufficient to explain the extent of wage disparities in the hotel industry. Consequently, there is a gap in the literature, which will be explored in this study because the present research seeks to understand the relationship among all the three elements of HRM performance. The techniques adopted by the researcher in undertaking the investigation are discussed in chapter three below.

Methodology

This chapter highlights the methods and techniques used by the researcher to meet the objectives of the study. Key tenets of this analysis will explain the research approach, design, philosophy, data collection processes, and analysis methods used in the study. Additionally, in this chapter, an explanation of the sampling procedures, ethical processes followed and limitations of the study will be outlined.

Research Philosophy

The philosophy underpinning a research investigation is dependent on one’s understanding of how data should be collected and analyzed. According to Patten and Newhart (2017), there are four main types of philosophies used in research studies. They include pragmatism, interpretivism, positivism, and realism. In this investigation, the positivism research approach was used in the study because the study aims to understand the relationship between working hours, wage differentials, and its impact on organizational justice. The positivism research approach was appropriate or this investigation because it presupposes that the social world can be evaluated and understood objectively. Using this line of reasoning, the researcher becomes a “scientific tool” aimed at investigating a research phenomenon without imposing personal values. Based on these characteristics, the positivism research philosophy underpinned this research investigation.

Research Approach

There are two main research approaches used in academic studies, qualitative and quantitative techniques. Researchers who intend to measurer numeric variables use the quantitative method, while qualitative research is often adopted in investigations that have subjective variables. Based on this classification, the quantitative research technique was selected for use in the current study because the research variables were measurable. Furthermore, the technique aligns with the nature of the research topic, which is similarly quantitative as it focuses on wage differentials. The qualitative research approach could not have been used in this investigation because the research objectives were quantitative in nature. For example, the need for measuring and quantifying relationships between and among variables was a quantitative process, which required a research approach that had similar characteristics.

Research Design

The research design selected for this study aligns with the aforementioned research approach. According to Stokes (2017), four main types of designs are associated with quantitative investigations: descriptive, correlation, quasi-experimental, and experimental. The correlation research design was selected for use in this study because it helped the researcher to determine the extent of the relationship between variables. The nature of this study is consistent with this design because the study aims to examine the prevalence and impact of unbalanced working hours to reward ratio in the hotel sector. The correlation research design is appropriate to use in such type of an investigation because it is equipped to establish relationships between or among variables. Using statistical data, this type of research design is equipped to recognize trends and patterns in data, which will be used to meet the research objectives.

Data Collection

The data collection process highlights mechanisms used by the researcher to obtain information from respondents. Based on the nature of evidence to be collected, data relating to the research was gathered using questionnaires and sentiments measured using a five-point Likert scale. The justification for using the survey method to collect data is enshrined in its widespread use in business-related research studies. The simplicity of surveys and the ability to collect large volumes of data were also other motivators for using the technique.

Sample Population

The researcher initially sought the views of 300 workers who were sourced from hotels. However, in one organization, management prevented workers from taking part in the survey because doing so would have contravened specific provisions of their contractual agreements. This problem reduced the number of remaining participants to 198. A further 56 respondents did not submit their questionnaires on time for review and were unreachable on phone, thereby reducing the count to 142 informants. A further 30 respondents submitted their questionnaires but the documents contained missing or invalid data. Therefore, they were eliminated from the study. These events led the researcher to remain with 112 complete and valid questionnaires, which formed the basis for the development of this study’s findings.

Sampling Technique

A sampling technique defines the framework for selecting respondents who took part in the investigation. The simple random sampling method was used to select respondents who took part in the study. It was adopted because of its objectivity in data collection. In other words, it is free from a researcher’s bias because every respondent who took part in the study had an equal chance of taking part in the investigation. Therefore, the simple random sampling method was justifiably used in this study because of its objectivity in recruiting participants. Kara (2015) supports its use in quantitative studies that involve a large number of respondents because it gives each employee equal probability of opportunity to take part in the research. Therefore, the context of the study was a significant motivator for the use of the above-mentioned sampling method because the research study was relevant to the hotel sector, which is an extensive industry to cover. Thus, the main motivation for pursuing this sampling strategy was to minimize researcher bias in such a context.

Data Analysis

Data was analyzed using the Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software – version 23. This data analysis technique was used in this study because other researchers and professionals have successfully employed it while undertaking similar data analysis processes. For example, Denis (2018), Wilson and Lorenz (2015) say that government agencies, marketers, data miners, and even companies that conduct surveys for corporate clients extensively use the software to perform market research. Stemming from the use of the SPSS software described above, descriptive and correlation analysis tools were used to analyze quantitative data.

Ethical Considerations

The integrity of a research process is partly protected by the ethical principles that guide it. The ethical implications of a study refer to the conduct of researchers in the course of undertaking their studies. In line with this view, Ababneh et al. (2020) and Petillion et al. (2017) say that addressing the ethical considerations of a research study is an important step in reducing bias and improving compliance with relevant laws and policies governing research investigations. Particularly, the use of human subjects in research demands that a researcher protects and respects their rights throughout an investigation. Petillion et al. (2017) support this view by saying that studies involving human subjects are often subject to ethical considerations to protect the rights of informants. To this end, several ethical considerations were observed in the study. Key among them was the need to protect the privacy of respondents who took part in the investigation and obtain their consent to be recruited in the study. Therefore, all the participants who took part in the research did so voluntarily.

The researcher also provided the informants with information relating to the aim and objectives of the study to get sufficient data for making an informed decision on whether to take part in it, or not. In other words, they were not coerced or given financial incentives to take part in the study. Additionally, the researcher presented the respondents’’ views anonymously, meaning that their identities were protected, including their job positions, organizations, and employers. The aim of doing so was to prevent attempts of victimizing the informants for the views they gave in this study. Furthermore, the information obtained from this investigation was stored in the researcher’s computer and the contents protected using a password. Doing so helped to prevent unauthorized access to the research data collected. Upon completion of the study, the information collected was destroyed to preserve the integrity of the data collected. It is expected that the above-mentioned ethical procedures were sufficient in protecting the respondents from all possible harm that could affect them because of participating in the study.

Limitations of the Study

The use of the correlation research design has been highlighted as a key tenet of this research design. However, investigating the correlation between and among variables is a limitation in this study because the scope of the investigation did not cover causation. This limitation has emerged because this study is observational and does not necessarily seek to explain the cause and effects of the variables analyzed. Instead, only the relationships underpinning the data obtained were examined. In other words, the researcher did not manipulate the variables and only observed themes that appeared in the study setting. This limitation explains why correlation research studies are also described as a form of descriptive research because a researcher does not manipulate any of the variables analyzed (Stokes, 2017). Additionally, another limitation of this study is its indicative nature. In other words, the evidence and findings outlined in this report only seek to guide policymaking and are not necessarily context-specific. In other words, they are not specifically designed to solve wage gap differences in a specific organization, because they are developed to indicate the overall state of affairs underpinning the relationship between working hours and remuneration in the hotel sector.

Results and Discussion

In this section of the paper, the findings derived from implementing the research strategies outlined in chapter 3 above are reported. The results will later be compared and contrasted with the information highlighted in chapter two to identify consistencies or inconsistencies. Key sections of this chapter will explain the demographic findings of the study as well as the respondents’ views regarding the research questions. To recap, the researchers sought their views using a survey questionnaire that explored four key issues about the research aim: working hours, employee wellbeing, compensation, and organizational justice.

Demographic Data Findings

The first part of the survey questionnaire sought to find out the respondent’s age, gender, and education levels. This information was later used to evaluate whether the demographic characteristics of the respondents affected the overall findings. The results are highlighted below.

Gender Findings

According to table 4.1 below, most of the respondents who took part in the study were male (52.7%), while females were 47.3% of the total sample of participants.

Table 4.1 Gender Findings (Source: Developed by Author).

Age Findings

Age was the second demographic variable highlighted in this study. According to table 4.2 below, most of the respondents (49.1%) who took part in the study were between 18 and 30 years. The second-largest group of respondents was between 31 and 40 years old and they represented 21.4% of the total sample of participants. Those who were between the 41-50 age range comprised the third largest group of respondents (17%), while those who were above 60 years formed the fourth largest group of informants comprising of about 11.6% of the total sample. Additionally, only one respondent was between 51 and 60 years and she represented 0.9% of the total sample.

Table 4.2 Age Findings (Source: Developed by Author).

Education Qualification Findings

Employees who took part in the investigation were also asked to state their highest verifiable education qualification. According to table 4.3 below, most of them (58%) had a high school education certification. Comparatively, informants who had a bachelor’s degree certificate formed the second largest group of respondents (18.8%), while those who had a diploma certificate formed 17% of the total sample. The smallest group of respondents was made up of employees who had an advanced diploma. They formed 6.3% of the total number of respondents who took part in the study.

Table 4.3 Education Qualification Findings (Source: Developed by Author).

Employee-Management Data Findings

The findings depicted in this section of the report relate to the second part of the questionnaire that sought to sample employees’ views regarding the relationship between working hours, compensation, and its effects on organizational justice. In this section of the questionnaire, the respondents were supposed to react to different statements relating to varied areas of the above-mentioned relationship, including their views on working hours, employee wellbeing, compensation, and organizational justice. The findings are highlighted below.

Working Hours

The first part of the questionnaire sought to sample the views of the respondents regarding the number of hours worked. In this section of the analysis, the respondents were supposed to react to four issues highlighted below.

Adequate Hours in Job Group

The first statement sought to find out the respondents’ views on the adequacy of hours worked and most of them (38.4%) “disagreed” with the view that they worked adequate hours in their job groups. Furthermore, 35.7% of the respondents held neutral views regarding the same issue to imply that they “neither agreed nor disagreed” with the aforementioned issue. A broader overview of the findings is presented in table 4.4 below.

Table 4.4 Adequate hours in job group (Source: Developed by Author).

Time off Work

The second statement posed to the respondents sought to find out whether employers gave workers time off work if it was justified to do so. As highlighted in Table 4.5 below, a majority of the respondents either “strongly agreed” (40.2%) or agreed (44.6%) with this statement.

Table 4.5 Time off work (Source: Developed by Author).

Fluctuating Work Schedules

The next statement posed to the respondents sought to find out their views about fluctuating work schedules. According to table 4.6 below, most of them (45.5%) agreed with the statement that their job demands lead to fluctuating work schedules. The findings are summarized below.

Table 4.6 Fluctuating work schedules (Source: Developed by Author).

Availability of Workers to Complete Work Schedules

Respondents were also supposed to give their views regarding the availability of workers to complete work schedules and none of them “disagreed” or “strongly disagreed” with the statement stating that there were often few workers in the organization to complete work obligations on time. Conversely, a majority (51.8%) of them either “strongly agreed” or “agreed” (34.8%) with this statement. A broader overview of the findings is presented in table 4.7 below.

Table 4.7 Availability of Workers to Complete Work Schedules (Source: Developed by Author).

Employee Wellbeing

The second set of statements that the respondents reacted to was linked to their wellbeing. In this section of the survey, the informants were required to react to three statements touching on work-family conflict, work stress, and employer concerns about employee wellbeing.

Work-Family Conflicts

The first statement related to work-family conflicts and a majority of them (51.8%) held “neutral” views on this matter, meaning that they neither agreed nor disagreed with the view that their work caused them this type of conflict. A broader overview of the findings is highlighted below.

Table 4.8 Work-Family Conflicts (Source: Developed by Author).

Work Stress

The next statement posed to the respondents sought to find out their views regarding the presence of work stress. Most of the respondents (46.4%) disagreed with the statement that work stresses them out, while the second-largest group of respondents (35.7%) held neutral views about the same statement. A broader overview of the findings is presented in table 4.9 below.

Table 4.9 Work Stress (Source: Developed by Author).

Employer Concerns about Employee Wellbeing

Linked to the above findings, the respondents were also asked to react to the statement, that their employers showed concern for their wellbeing. This statement attracted the least diversity of responses because most of the informants (75%) either “strongly agreed” or “agreed” (25%) with this statement. Table 4.10 below summarises these findings.

Table 4.10 Employer Concerns about Employee Wellbeing (Source: Developed by Author).

Compensation

The next part of the investigation in the questionnaire focused on compensation. The respondents were supposed to react to four statements linked to this issue: fairness in compensation, adequacy of salary, promotion policies, and types of compensation. The findings are highlighted below.

Fairness in Compensation

Table 4.11 below shows that most of the respondents believed that they received fair compensation for the work they did. This statement is supported by the fact that a majority of the respondents (39.3%) “Agreed” with this statement. A further 32.1% of the total sample of respondents “strongly agreed” with the same view, while a further 28.6% held neutral positions. The findings are summarized below.

Table 4.11 Fairness in Compensation (Source: Developed by Author).

Adequacy of Salary

The next statement made by the respondents related to the adequacy of salary received and most of them (51.8%) “Strongly” held the view that they received adequate salaries, while a further 42.9% “agreed” with the same position. Only 5.4% of the total sample held “neutral” views regarding this statement. A broader overview of the findings is highlighted in table 4.12 below.

Table 4.12 Adequacy of Salary (Source: Developed by Author).

Promotion Policies

In the next statement, the respondents were supposed to react to related to promotion policies in their organizations. As highlighted in Table 4.13 below, most of the respondents (38.4%) “strongly agreed” with the statement that their organizations’ promotion policies were based on merit and employee contribution. Additionally, 33.9% of the total sample also “agreed” with the same statement, while a further 13.4% of the sample held “neutral” views.

Table 4.13 Promotion Policies (Source: Developed by Author).

Types of Compensation

The last statement relating to employee compensation sought to find out the employees’ views regarding the presence of different forms of rewards for their contributions to their organizations. A majority of them (48.2%) “strongly agreed” with the statement that their employers provided different forms of compensation, while 25.9% of them “agreed” with the same position. A broader overview of the findings is presented in table 4.14 below.

Table 4.14 Types of Compensation (Source: Developed by Author).

Organizational Justice

The last part of the survey results related to organizational justice. In this section of the analysis, the respondents were supposed to react to three statements focusing on the fairness of compensation policies, type of work environment, and management support. The results are outlined below.

Compensation Policies

The first statement probed the employees’ understanding of whether management adopted fair compensation policies for hours worked. According to the findings highlighted in table 4.15 below, most of them (40.2%) disagreed with this statement.

Table 4.15 Compensation Policies (Source: Developed by Author).

Work Environment

The next statement that the informants reacted to focused on the presence of a supportive work environment that would allow them to address unfairness in compensation practices and a majority of the respondents (41.1%) were undecided on this matter. Table 4.16 below shows a broader overview of the findings.

Table 4.16 Work environment (Source: Developed by Author).

Management Support

The last statement that the informants reacted to related to the need for extra support from management to improve their wellbeing. According to the findings highlighted in table 4.17 below, a majority of the informants (77.7%) “strongly agreed” with the statement, insinuating the need for extra management support in improving compensation policies.

Table 4.17 Management Support (Source: Developed by Author).

Correlation Findings

As highlighted in the introduction section of this chapter, four key issues about the research aim were explored – working hours, employee wellbeing, compensation, and organizational justice. The findings highlighted in table 4.18 below highlight the correlation between the four variables highlighted above.

Table 4.18 Correlation Findings (Source: Developed by Author).

According to the findings highlighted above, the variables did not share correlation, meaning that working hours were not linked to compensation levels, employee wellbeing, or organizational justice. This is because all the variables identified above had correlation values that were higher than p>0.05, which is the significance level. The next step of the evaluation process involved understanding whether any of the three demographic variables identified in this chapter (age, education level, and gender) affected these results and the findings are highlighted below.

Impact of Demographic Variables

Gender was one of the variables analyzed in this study. Its effects on the variables analyzed are presented in table 4.19 below.

Table 4.19 Impact of gender on findings (Source: Developed by Author).

According to the findings highlighted above, gender did not play a significant role in influencing the respondents’ views because the significance value was higher than p>0.05. For example, organizational justice had a significance value of 0.722, which is higher than 0.05. The same is true for compensation, employee wellbeing, and working hours. The effects of education on the same variables are highlighted in table 4.20 below.

Table 4.20 Impact of education levels on findings (Source: Developed by Author).

Similar to the findings investigating the impact of gender on the variables, education also did not have an impact on the respondents’ views. This is because the significance values were above P>0.05. For example, compensation had a significance value of 0.870, while organizational justice had a significance value of 0.261. Employee working hours and wellbeing also posted significance values higher than p>0.05, meaning that the respondents’ education levels did not affect their views on the study. The impact of the respondents’ age on their findings is highlighted in table 4.21 below.

Table 4.21 Impact of age on findings (Source: Developed by Author).

According to the findings highlighted above, age had no effect on the respondents’ views regarding working hours, employee wellbeing, and compensation. However, it affected the respondents’ views on organizational justice. This effect could stem from generational differences between different groups of employees who work in the hotel industry. Particularly, older workers could have a different view from their younger counterparts regarding fairness and justice in employee compensation. For example, older workers could be willing to take a lower pay compared to their younger counterparts because of varying levels of commitment towards their job.

Alternatively, younger workers could be motivated by the increase in employment opportunities available today to demand better terms of remuneration from their employers. Therefore, they would perceive an employer who does not meet their demands as being “unjust” compared to an older worker who grew up in an environment characterized by scarcity. The impact of age on organizational justice could be further traced to differences in work ethic between older and younger workers. Several researchers have narrowed the analysis to differences in perceptions between millennial workers and the baby boomer generation (Chawla et al., 2017). For example, according to Omilion-Hodges and Sugg (2019), the aforementioned generational differences could be explained by differences in perceptions about work between millennials and “baby boomers.”

Conclusion and Recommendation

From the onset of this study, the goal has been to examine the prevalence and impact of unbalanced working hours to rewards ratio in the hotel sector. To meet this research aim, three objectives were formulated. The first one was designed to quantify the relationship between working hours and financial compensation received by employees in the industry and the second one was aimed at measuring the effects of the relationship between unbalanced working hours to reward ratio on employees’ perceptions of organizational justice in the hotel sector. The third objective was designed to estimate the prevalence of unbalanced working hours to rewards ratio in the hotel sector. The findings revealed that there was no relationship between working hours and financial compensation. Furthermore, the evidence gathered in the study indicated that wage differentials were not widespread. These findings are inconsistent with the majority of the literature, which suggests a correlation between working hours and financial compensation.

Stemming from the above findings, the researcher did not find evidence indicating that the influence of unbalanced working hours to reward ratio influenced employees’ perceptions of organizational justice. The inconsistency of the findings highlighted above could stem from the favorable labor policies prevalent in today’s labor market, which have improved working conditions for most employees and boosted their satisfaction level as well. This statement means that these conditions should have neutralized the effects of unbalanced working hours and employee compensation that has been reported in other studies. However, it is also important to note that a significant percentage of the informants sampled in this study also held contrary views regarding the research issue and age accounted for most of the variations in responses witnessed in the findings. In this analysis, low-skilled employees could have held contrary views regarding the favorability of employee matters, indicating that there is still some room for improvement.

Overall, the role of rewards in boosting employee performance has been an essential topic of inquiry in human resource management literature. In the hotel sector, this relationship is crucial because rewards are connected to employee motivation and performance, which, in turn, affect productivity and customer satisfaction. Ensuring that the relationship between rewards and employee outcomes is understood and implementation gaps addressed, could help to enhance HRM practices, bringing better performance and productivity to companies. Alternatively, this process is instrumental in developing a combined policy action among stakeholders in the hotel industry, thereby improving their relationships. Thus, it will provide a foundation for galvanizing more efforts to address wage gap inequalities as a broader HRM problem in the hotel sector.

Recommendations

Broadly, there is a need to increase investments in the provision of decent and sustainable work to reduce the pay gap inequities in the hotel industry. Particularly, this approach could be more useful in low-income countries because the pay gap is wider among low-skilled and highly skilled employees. Particularly, rapidly industrializing nations, such as China and India could find such information useful in managing labor issues in their economies. More importantly, they could find these insights to be useful in supporting their struggling tourism markets as labor dynamics tend to apply to multiple industries. The contributions made by these insights to the above-mentioned economies could happen by providing strong business incentive structures to oversee the improvement of wages among of workers. Particularly, the creation of paid employment frameworks for many low-skilled workers at the bottom of the pay pyramid needs to occur if lasting changes are to be made to improve employee performance and organizational output. For example, employees who work on a casual basis may be incentivized to improve their work terms and make their employees have the benefits of a permanently employed worker. This strategy will minimize the pay discrepancies between employees who are contracted on a casual or permanent basis.

The second strategy that can be adopted in the hotel industry to minimize pay gap inequalities involve increasing investments in work institutions. The process should first start through the development of a wage determination mechanism that would outline the framework for setting wages and outline modalities for improving it over time. For example, enhancing employee fundamental rights and limiting working hours among certain job groups would improve the profile of low-skilled employees and increase their chances of earning better wages. Alternatively, raising the minimum wage to a level that is substantially high and that can cover the basic needs of all employees would also be a welcome step in minimizing wage disparities linked to unbalanced working hours. Doing so would introduce dignity to low-skilled workers who may feel trapped by low wages and a rising standard of living.

In this discussion, the minimum wage should be seen as a starting point for challenging traditional norms and patterns of engagement among different groups of workers. However, minimum wages should not be merely set at a certain price point and assumed to have solved the traditional power imbalance between employers and employees because managers also need to do more work in creating new opportunities for workers to generate additional revenue from their work. Therefore, this policy complements existing HRM policies aimed at improving employee welfare by periodically increasing the minimum wage. This practice is prevalent around the world and in many countries as different labor organizations often advocate for better pay and remuneration from their employers by requesting an increase in their minimum wages.

By following the above-mentioned strategy, progress has been achieved in various sectors of the economy, such as through the success of labor unions, which have managed to highlight unfair remuneration policies by organizations that pursue profits at the expense of workers’ welfare. Similarly, they have achieved success in improving employee working conditions by demanding better compensation for extra hours worked. Therefore, increasing investments in people’s abilities should be a welcome step because it may help to minimize wage inequalities in the hotel sector. This could happen by providing new educational opportunities for workers to improve their skills. Training and seminars could also be organized to improve the level of skills required of employees in the 21st-century workplace.

References

Ababneh, M. A., Al-Azzam, S. I., Alzoubi, K., Rababa’h, A., & Al Demour, S. (2020).

Understanding and attitudes of the Jordanian public about clinical research ethics. Research Ethics, 7(2), 1-10.

Artazcoz, L., Cortès, I., Benavides, F. G., Escribà-Agüir, V., Bartoll, X., Vargas, H., & Borrell, C. (2016). Long working hours and health in Europe: Gender and welfare state differences in a context of economic crisis. Health & Place, 40(1), 161–168.

Boella, M. J., & Goss-Turner, S. (2020). Human resource management in the hotel industry: A guide to best practice (10th ed.). Routledge.

Brotherton, B. (2015). Researching hotel and tourism (2nd ed.). Sage.

Casado-Díaz, J. M., & Simón, H. (2016) Wage differences in the hotel sector. Tourism Management, 52(1), 96–109.

Chawla, D., Dokadia, A., & Rai, S. (2017). Multigenerational differences in career preferences, reward preferences, and work engagement among Indian employees. Global Business Review, 18(1), 181–197.

Denis, D. (2018). SPSS data analysis for univariate, bivariate, and multivariate statistics. John Wiley & Sons.

Iddagoda, Y. A., & Opatha, H. H. D. N. P. (2020). Relationships and mediating effects of employee engagement: An empirical study of managerial employees of Sri Lankan listed companies’, SAGE Open., 4(1), 1–11.

ILO. (2020). Understanding the gender pay gap. International Labour Organization. Web.

Imran, R., Majeed, M., & Ayub, A. (2015). Impact of organizational justice, job security, and job satisfaction on organizational productivity. Journal of Economics, Business, and Management, 3(9), 840–845.

Joo-Ee, G. (2016). Minimum wage and the hotel industry in Malaysia: An analysis of employee perceptions. Journal of Human Resources in Hotel & Tourism, 15(1), 29–44.

Kara, H. (2015). Creative research methods in the social sciences: A practical guide. Policy Press.

Kim, K. Y., Atwater, L., Jolly, P. M., Kim, M., & Baik, K. (2020). The vicious cycle of work-life: Work effort versus career development effort. Group & Organization Management, 45(3), 351–385.

Lee, Y. K., Kim, S., Son, M. H., & Kim, M. S. (2015). Linking organizational justice to job performance: Evidence from the restaurant industry in East Asia. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 20(1), 1527–1544.

Nightingale, M. (2019). Looking beyond average earnings: Why are male and female part-time employees in the UK more likely to be low paid than their full-time counterparts? Work, Employment and Society, 33(1), 131–148.

Omilion-Hodges, L. M., & Sugg, C. E. (2019). Millennials’ views and expectations regarding the communicative and relational behaviors of leaders: Exploring young adults’ talk about work. Business and Professional Communication Quarterly, 82(1), 74–100.

Patten, M. L., & Newhart, M. (2017). Understanding research methods: An overview of the essentials. Taylor & Francis.

Petillion, W., Melrose, S., Moore, S. L., & Nuttgens, S. (2017). Graduate students’ experiences with research ethics in conducting health research. Research Ethics, 13(3), 139–154.

Pradhan, R. K., & Jena, L. K. (2017). Employee performance at the workplace: Conceptual model and empirical validation. Business Perspectives and Research, 5(1), 69–85.

Prasad, A. (2019). Untapped relationship between employer branding, anticipatory psychological contract, and intent to join. Global Business Review, 20(1), 194–213.

Rosemberg, M. A. S., & Li, Y. (2018). Effort-reward imbalance and work productivity among hotel housekeeping employees: A pilot study. Workplace Health & Safety, 66(11), 516–521.

Roxo, L., Bambra, C., & Perelman, J. (2020). Gender equality and gender inequalities in self-reported health: A longitudinal study of 27 European countries from 2004 to 2016. International Journal of Health Services, 2(3), 1-10.

Ryu, G. (2016). Public employees’ well-being when having long working hours and low-salary working conditions. Public Personnel Management, 45(1), 70–89.

Shuck, B., Nimon, K., & Zigarmi, D. (2017). Untangling the predictive nomological validity of employee engagement: Partitioning variance in employee engagement using job attitude measures. Group & Organization Management, 42(1), 79–112.

Stokes, P. (2017). Research methods. Palgrave Macmillan.

Sturman, M. C., Ukhov, A. D., & Park, S. (2017). The effect of the cost of living on employee wages in the hotel industry. Cornell Hotel Quarterly, 58(2), 179–189.

Tanwar, K., & Prasad, A. (2016). Exploring the relationship between employer branding and employee retention. Global Business Review, 17(3), 186–206.

Ugaddan, R. G., & Park, S. M. (2019). Do trustful leadership, organizational justice, and motivation influence whistle-blowing intention? Evidence from federal employees. Public Personnel Management, 48(1), 56–81.

Wilson, J., & Lorenz, K. A. (2015). Modeling binary correlated responses using SAS, SPSS and R. Springer.

Witts, S. (2015). The hotel industry shamed over the gender pay gap. Big Hotel. Web.