Introduction

From psychology and the social sciences, we know a lot about the social properties of having different sorts of social relationships. For example, with close friends, we share or exchange lots of different activities and resources. Whereas for strangers, our exchanges are almost exclusively about exchanges of money for activities and resources (Guerin, 2016). Other key social properties include:

- What resources are exchanged between the persons?

- How much they each know about other social relationships they might have.

- How much they tell or keep secret from each other.

- How much they try and check what they are told.

- How much they have interdependent exchanges that rely on each other.

- How much they exchange in a reciprocal or one-sided way.

- How contexts of trust appear.

- What obligations are reported.

- How they maintain an image of themselves to the other and what image that is.

- What each can get the other to do.

- How much they would help them or provide help in life in case it was needed.

These properties shape and maintain our social relationships. In this way, we can analyze people’s social behaviors. When an unexpected behavior occurs, we can then look for other contexts which might be changing the pattern normally found. Social relationships are not static, and changes occur both within people’s lives and across generations. That said, the transition points for human social relationships – especially emerging adulthood and older life (Baker, 2012; Blieszner et al, 2019; Yavuz Güler et al., 2022) – are not well known and change with cultural and technological changes (Katz et al., 2021).

Therefore, it is important to take stock of the ways in which people form new friendships, how friendships are maintained through their life span, and what economic, cultural, opportunities, and other social contextual influences help or hinder the establishment and maintenance of an adult friendship (Laursen, 2017). This report will analyze several interviews on this topic to understand some of these processes and focus in on a particular aspect as a research question.

Research Question

What factors contribute to the dissolution of friendships among university students?

Methodology

Ethics

An informed consent form was used to provide participants with thorough information about the study’s purpose, benefits, and risks, allowing for an educated decision-making process. Furthermore, anonymity was preserved by obtaining no directly identifying data, ensuring that participants’ names remained unknown. To avoid potential participants from getting worried about their personal data, the researcher assured the participants that their data responses were to be anonymized and no third party were privy to the data (see Appendix A).

Participants

The face to face interview was open from November 1st to November 8th, 2023, and had 12 participants for a response rate of 25%. To choose participants, an intentional sampling strategy was utilized. Members of the campus-based project were chosen for participation, and all were asked to participate, ensuring a representative sample of the student population. The sample was racially varied, with one Iranian female, five females and three male of Asian Australian ancestry, and one female and two males of Caucasian origin.

Participants were identified as having little intellectual or developmental impairments or no developmental disabilities, which formed the first question of the interview questions as attached in Appendix A. Despite these challenges, all students demonstrated competent communication skills, allowing for meaningful involvement in the study. This deliberate inclusion of persons with and without minor intellectual or developmental impairments aligns with the research purpose of investigating diverse perspectives on friendship breakdown in the university environment. The demographic mix reflects the university environment’s complexity, ensuring that the findings reflect a varied range of experiences among students of different backgrounds and abilities.

To keep the study’s focus and ethical issues intact, exclusion criteria were applied. To guarantee that participants could contribute to the research, students with significant cognitive or developmental impairments, as well as those without functional communication abilities, were excluded. The goal of this deliberate selection criterion was to preserve the ethical norms of voluntary participation and respect for the research participants’ capacities. By setting explicit exclusion criteria, the study tried to strike a compromise between inclusion and participants’ capacity to give important viewpoints on the phenomenon of relationship breakup within the university context.

Processes

Participants for this study on university students’ experiences were recruited using open communication channels. The project’s goals were presented, and those who exhibited interest were informed on the research. Prior to data collection, informed consent was acquired from the students, and the importance of volunteer participation was emphasized.

To promote participation, participants received a gift voucher at the beginning and upon completion of the study. Demographic data, which was required to contextualize responses, contained a wide variety of attributes. Participants varied in age from 18 to 25, covering a greater period of transition in university life. There were seven females and six males in the group, with no individuals identifying as non-binary or belonging to alternative gender identities. Regarding academic majors, participants represented various disciplines: Four participants came from the social sciences, three from the health sciences, four from the arts, and one from engineering.

The inclusion of such diverse academic backgrounds allowed for a comprehensive exploration of university experiences across different fields of study. This variation in majors ensured that perspectives from multiple disciplines could be considered when analyzing the data collected. It also provided an opportunity to examine potential differences or similarities in experiences based on academic focus.

To preserve participant confidentiality, a comprehensive cleaning procedure followed the initial data collection. This involves eliminating any identifiable information before assigning pseudonyms to participants in order to protect their privacy. Furthermore, any extraneous data points that did not contribute to the research objectives were eliminated during the data cleaning phase. These strong safeguards were put in place to maintain the study’s integrity and the ethical management of participant information. The data was organized using a deductive coding approach that was led by pre-existing group codes and themes (Bingham & Witkowsky, 2022). The coding technique involved categorizing responses into predefined categories, allowing for orderly thematic analysis. Several readings and team discussions improved the coding methodology’s reliability and validity.

Thematic analysis, which was chosen for its capacity to discover patterns in the dataset, enabled themes to emerge from grouped codes. The study team engaged in a reflective approach throughout the examination, examining preconceptions and biases. The study used a face to face interview methodology to generate the data set used for this analysis and to delve into the relationships between friendships and student disintegration experiences, offering depth and context.

One month before semester exams, students were interviewed and reported their semester experiences. The interviews were semi-structured and focused on communication, expectations, and psychological elements. Braun and Clarke’s framework was used to examine the data, and themes were improved through a theoretical phase using Kahu et al.’s (2020) student participation framework (Byrne, 2022; Kahu et al., 2020). All data was non-identifiable due to the use of participant pseudonyms, with this research focusing on friendship dynamics among university students.

Results

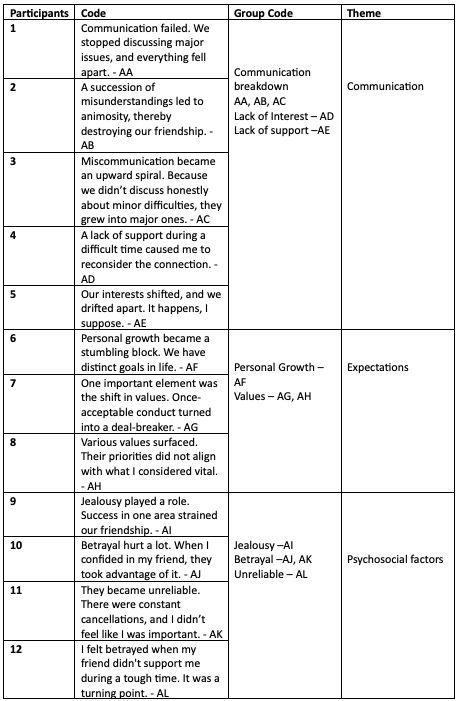

The outcomes of the study demonstrate how friendships impact students’ experiences with university participation. Students have not considered any of the other possible benefits of friendships other from social consequences (see Table1: Appendix B). This study’s thematically structured findings depict a relationship journeys. The first is the students’ expectations about friendships, and the second is the psychosocial elements that made it easier for friendships to dissolve. The final subject was lack of communication as a negative of friendships, which leads to disintegration.

Communication

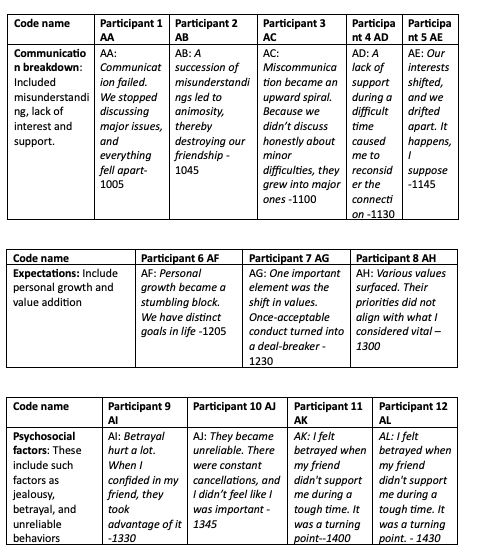

Communication, as a fundamental part of human connection, is the foundation for forming and maintaining friendships. Effective communication entails the interchange of ideas, sentiments, and experiences those results in a common understanding among persons. Communication breakdown was coded as a sub-theme (see Table 2: Appendix C).

- AA: “Communication failed. We stopped discussing major issues, and everything fell apart.”

- AB: “A succession of misunderstandings led to animosity, thereby destroying our friendship.”

- AC: “Miscommunication became an upward spiral. Because we didn’t discuss honestly about minor difficulties, they grew into major ones.”

This phrase stresses the significant impact that a breakdown in communication has on the whole fabric of friendship. When vital interactions stop, the friendship becomes subject to misunderstanding and misalignment, leading to its demise. The loss of support is another sub-theme under communication.

- AD: “A lack of support during a difficult time caused me to reconsider the connection.”

- AE: “Our interests shifted, and we drifted apart. It happens, I suppose.”

The statements emphasize how a breakdown in communication may destroy a friendship’s support structure. Friends express and provide support through effective communication, and its absence can strain the links that hold the relationship together. Lastly, the sub-theme of loss of interest owing to a lack of communication is present within the topic of communication.

Expectations

Expectations in a university relationship situation include shared aims, mutual understanding, and a sense of reciprocity. These possibilities serve as the foundation for the relationship’s predicted trajectory, impacting how persons see and interact with one another. As shown in Table 1, the reasons why two university students’ friendships break are unfulfilled shared personal improvement and disappointed expectations from their friends. The sub-theme of personal progress appeared as a prominent feature within the wider topic of expectations (see Table 2: Appendix C).

- AF: “Personal growth became a stumbling block. We have distinct goals in life.”

These accounts depict the difficulties that come when friends go on diverse paths of personal growth. The anticipation of developing together can become strained when individual ambitions diverge, causing a schism that can lead to the bond disintegrating.

- AG: “One important element was the shift in values. Once-acceptable conduct turned into a deal-breaker.”

- AH: “Various values surfaced. Their priorities did not align with what I considered vital.”

The remarks above capture the strain that occurs when predicted paths differ, resulting in natural drift. The gap between expectations and reality can lead to emotions of disappointment, putting the friendship’s basis in jeopardy. Evolving expectations can cause a mismatch of values, turning once-acceptable actions turn to deal-breakers. Individuals’ priorities alter as they mature, and friendships may fall apart when these developments result in irreconcilable conflicts.

Psychosocial Factors

Negative behaviors and psychological variables weave a complicated tapestry inside the fabric of friendships, altering their dynamics and results. The sub-themes include envy, conflicting values, and different complexities that highlight the delicate interaction of psychological elements. Jealousy and betrayal play an important influence in creating relationship dynamics among some of the questioned individuals. For example, participant five offered his thoughts and stated that their loss of relationship was due to envy, a psychological behavior among university friends (see Table 2: Appendix C).

- AI: “Jealousy played a role. Success in one area strained our friendship.”

Furthermore, the effect of achievement on interpersonal dynamics exposes the subtle but significant ways in which negative emotions can unravel the threads of connection. In this example, betrayal, a significant sub-theme, emerged in participant narratives. Fear of the consequences of admitting the betrayal may cause the betrayed person to bury the trauma. According to Suppes (2022), social exchange theory posits that people, for instance, friends, employ social relations with a hope of receiving benefits. However, when trust is eroded in a mutual friendship, it is often because there are apparent cracks in the reciprocity of connections.

- AJ: “Betrayal hurt a lot. When I confided in my friend, they took advantage of it.”

- AK: “They became unreliable. There were constant cancellations, and I didn’t feel like I was important.”

- AL: “I felt betrayed when my friend didn’t support me during a tough time. It was a turning point.”

AL’s assertion captures the devastating impact of betrayal on the foundation of trust between friendships. Betrayal causes a profound and sometimes irreversible split in the relational structure, contributing to the unraveling of friendships. In addition, the AK statement underlines the psychological consequences of untrustworthy behavior on friendship stability. The feeling of being undervalued because of unreliability provides an element of instability that might destroy the foundation of trust and connection. Therefore, the consequences of negative behaviors characterized by untrustworthiness can inflict lasting damage upon friendship relationships.

Discussion

University students’ friendships have a significant impact on their overall experiences and participation with academic life. Communication, expectations, and psychological aspects all indicated complex dynamics within these partnerships. Communication breakdown revealed as a crucial component, matching prior findings that emphasize excellent communication as vital for maintaining successful connections (Allan, 2021). Participants’ stories underscored the negative impact of communication breakdown on friendship, which leads to misunderstandings, resentments, and disintegration. This is consistent with current work that emphasizes the value of open discussion in maintaining meaningful connections (Felten & Lambert, 2020).

University connections showed expectations as a multidimensional issue comprising shared aims, personal progress, and shifting priorities. The finding supports previous research that emphasizes the importance of expectations in friendship durability (Hajek & König, 2021). Unmet expectations and divergent pathways in personal growth identified as significant reasons to friendship breakdown. Tinto’s (1975) theory, emphasizing the significance of social integration in student retention, supports the findings, implying that disappointed expectations may impede this integration (Braxton, 2019).

Psychosocial variables such as jealousy, betrayal, and dependability added levels of complication to friendship interactions. Negative behaviors had a noticeable influence on friendships, correlating with prior study that identified envy and betrayal as possible disruptors in social relationships (Blayney & Burgess, 2023). The study’s findings are also consistent with betrayal trauma theory, highlighting the long-term consequences of injury in attachment relationships (Fung et al., 2023). Furthermore, friend unreliability revealed as a psychological component impacting friendship stability, resulting to a sense of deprivation and instability. The topic incorporates additional material on the good effects of friendship in university life. According to Kahu et al. (2020), positive relationship influences pupil engagement and retention. As a result, friendships are vital for students’ well-being because they help in the removal of such psychosocial limitations as jealousy, betrayal and reliability.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study sheds light on the dynamics of university friendships, emphasizing the critical importance of efficient communication, matched expectations, and the interaction of psychosocial elements in the maintenance of these relationships. This paper has answered the research question by noting the lack of communication, unmet expectations and psychosocial constrains are the main factors leading to the university students’ friendship dissolution. The incorporation of current literature insights improves this study’s understanding of the numerous contributions friendships make to the lives of university students.

While these findings provide useful information, it is important to recognize the study’s limitations, such as the presence of the researcher during the participant’s interview. The presence of the researcher during data collection, which, in this case, was unavoidable, might influence the participants’ responses. This constraint may have an influence on the validity and applicability of the findings, underscoring the importance of researcher’s involvement during data collection in a qualitative research.

Based on the conclusions presented above, future research should overcome the constraints by using third party interviewees. This improves the external validity of the findings and allows for more solid responses that are not bias or distorted. Furthermore, additional research might focus on the precise methods by which institutions can encourage and nurture healthy social ties among students. Investigating treatments and efforts that encourage effective communication, manage expectations, and traverse psychosocial issues might provide institutions with practical solutions to improve student engagement and overall well-being. In summary, this study paves the way for future research that contributes to the creation of focused support systems in academic contexts.

References

Allan, G. A. (2021). A sociology of friendship and kinship. Routledge.

Baker, D. (2012). All the lonely people: Loneliness in Australia, 2001-2009. The Australia Institute Research that Matters. Web.

Bingham, A.J., & Witkowsky, P. (2022). Deductive and inductive approaches to qualitative data analysis. In C. Vanover, P. Mihas, & J. Saldaña (Eds.), Analyzing and interpreting qualitative data: After the interview (pp. 133-146). SAGE Publications.

Blayney, R., & Burgess, M. (2023). Identifying points for therapeutic intervention from the lived experiences of people seeking help for retroactive jealousy. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 1-9. Web.

Blieszner, R., Ogletree, A. M., & Adams, R. G. (2019). Friendship in later life: A research agenda. Innovation in Aging, 3(1). Web.

Braxton, J. M. (2019). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition by Vincent Tinto. Journal of College Student Development, 60(1), 129-134. Web.

Byrne, D. (2022). A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Quality & Quantity, 56(3), 1391-1412. Web.

Felten, P., & Lambert, L. M. (2020). Relationship-rich education: How human connections drive success in college. Jhu Press.

Fung, H. W., Chien, W. T., Chan, C., & Ross, C. A. (2023). A cross-cultural investigation of the association between betrayal trauma and dissociative features. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38(1-2), 1630-1653.

Guerin, B. (2016). How to rethink human behavior: A practical guide to social contextual analysis. Routledge.

Hajek, A., & König, H. H. (2021). Do lonely and socially isolated individuals think they die earlier? The link between loneliness, social isolation and expectations of longevity based on a nationally representative sample. Psychogeriatrics, 21(4), 571-576. Web.

Kahu, E. R., Picton, C., & Nelson, K. (2020). Pathways to engagement: A longitudinal study of the first-year student experience in the educational interface. Higher Education, 79, 657-673. Web.

Katz, R., Ogilvie, S., Shaw, J., & Woodhead, L. (2021). Gen Z, explained: The art of living in a digital age. University of Chicago Press.

Laursen, B. (2017). Making and keeping friends: The importance of being similar. Child Development Perspectives, 11(4), 282–289. Web.

Suppes, B. C. (2022). Family systems theory simplified: Applying and understanding systemic therapy models. Taylor & Francis

Yavuz Güler, Ç., Çakmak, I., & Bayraktar, E. (2022). Never walk alone on the way: Friendships of emerging adults. Personal Relationships, 29(4), 811– 839. Web.

Appendix A

Interview Questions

By clicking ‘I consent ‘’you agree to participate in this research but understand that your participation is voluntary and that you can exit the interview at any time without explanation or penalty. We uphold privacy for any personal information provided in this interview.

Section A: Demographic

- Do you have any little intellectual or developmental impairment or no developmental disabilities?

- What is your gender?

- How old are you? Are you under 18 years, 19-25 years, 25-30 years or 31 years and above?

- What is your education major or areas of specialization? Does it fall under these major, Social Sciences, Health Sciences, Arts, Engineering? Please specify.

Section B: Relationship

At the university, have you ever ended a relationship with a fellow student? If yes, what led to the dissolution of the friendship? (Respond briefly.)

Appendix B

Appendix C