Abstract

Mergers and Acquisitions are old corporate strategies used by many companies to meet their goals. Different firms have unique motivations for choosing such strategic choices. Using a case study approach of LVMH, this paper focuses on the luxury brand segment to find out the main motivations why luxury brands choose the M&A strategy, the possible synergies they enjoy from choosing such strategies, and the value creation potential associated with the M&A strategy. The findings of this paper would help us to move a step closer to arriving at a conclusive position regarding why luxury brands, such as LVMH, have consistently pursued this strategy. Furthermore, they would help researchers who want to expand their body of knowledge regarding mergers and acquisition in the luxury brand segment to do so.

Introduction (Background)

According to Holliday (2015), there has been a dramatic increase in the number of Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) in the last few decades. Today, the global value of M&A transactions has surpassed the $5 trillion mark (BUSMAN 2014). While most M&A transactions have occurred in the United States (U.S), other parts of the world are now reporting increased numbers of such transactions (Miller 2011). For example, between the late 1990s and the early 2000s, the volume of European M&A transactions matched those in the U.S. Conversely, according to Teixeira (2011), different economic sectors have reported increased volumes of M&A transactions, among them being the luxury goods sector. Indeed, in the last decade, consolidation has characterized the luxury brand industry. Therefore, many companies have adopted M&A strategies to remain relevant, outwit their competition, and promote their brands.

LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton, better known as LVMH, is a pioneer company in the luxury brand segment that has been on the forefront in pursuit of the M&A strategy (Gaughan 2007). It has participated in several M&A deals within its sector, such as the purchase of an 80% controlling stake in Italy’s Cashmere Company, Loro Piana, for more than $2 billion (The American Graduate School of International Management 2013). In 2011, the company also entered into an M&A deal with Rome-based jeweler, Bulgari for $5 billion (Gaughan 2007). In 2010, the company also purchased minority shares in rival companies, such as Hermes International. LVMH has also acquired several small niche brands such as Ole Henriksen and Nude skin care in the last decade (Needle 2004). Based on these deals, the company has earned a reputation for being “predatory” (Teixeira 2011). Nonetheless, content with its strategic direction, the company’s brand development strategy and expansion plans have seen it open more than 3000 branches around the world (Hitt 2012). With more than 100,000 employees (80% of whom work outside France), LVMH has had a strong growth trajectory (Needle 2004). Using the LVMH as a case study, this paper focuses on finding out the impact of mergers and acquisitions on the Luxury brand segment.

Research Rationale

The luxury brand market is a multibillion-dollar industry (Kapferer 2012). Although researchers have associated mergers and acquisitions with increased value creation for companies that operate in this sector (Holliday 2015; Miller 2011), there are still unclear outcomes for luxury brand companies that pursue this strategy. For example, while some researchers say that M&As have created value for luxury brands (Vadapalli 2007), others posit that this strategy has decreased brand value for some of the mainstream luxury brands (Miller 2011). Most of the studies that have investigated M&A strategies have mainly focused on other economic sectors, besides the luxury brand segment (Sherman 2011; Kapferer 2012). For example, numerous volumes of research studies explain M&A in the banking and insurance sectors (Vadapalli 2007; Kapferer 2012). Comparatively, few studies explore M&A in the luxury brand segment.

To the extent that this study would find out the purpose and motivation for pursuing M&As in the luxury brand industry, its academic significance would be the increased volume of literature that relates this strategic approach to the industry’s needs. This way, we would move a step closer to arriving at a conclusive position regarding why luxury brands, such as LVMH, have consistently pursued this strategy. Furthermore, the findings of this study would help researchers who want to expand their body of knowledge regarding mergers and acquisition in the luxury brand segment to do so. Besides the academic significance of this paper, the findings of this study will also benefit luxury firms that intend to pursue the M&A strategy. Its findings will mainly be important to helping such firms to get value for pursuing this strategy and safeguard their interests in the deals. The research aim and objectives appear below

Research Aim and Objectives

Research Aim

The aim of this study is to find out why LVMH chooses the M&A strategy. Following this aim, this study has four main research objectives

- To explain LVMH’s purpose and motivation for pursuing a mergers and acquisition strategy

- To explain how LVMH chooses the mergers and acquisition strategy

- To understand the synergies LVMH could benefit by pursuing M&A

- To understand the value creation that LVMH pursues in M&A transactions

Research Questions

Based on the above research aim and objectives, this study adopted the following items as the main research questions

- What is LVMH’s purpose and motivation for pursuing an M&A strategy?

- What criterion does LVMH use to choose its M&A strategy?

- What synergies and values does LVMH pursue when adopting its M&A strategies?

Research Structure

This paper consists of six chapters. The first chapter is the introductory chapter and sets the stage for the rest of the paper. It provides the background of the study and explains the rationale for undertaking this research. The second chapter is the literature review section, which analyzes past studies that have focused on M&A strategies in the luxury goods sector. The third chapter is the methodology section, which outlines the processes, procedures and techniques underlying the study. The fourth chapter is the findings section, which describes the main themes and data pertaining to M&A strategies in the luxury good segments. Information from this paper provides the data for writing the fifth chapter (discussion and analysis), which relies on the study’s findings to answer the research questions and recommend further areas of analysis for future research. The last chapter is the conclusion.

Literature Review

Introduction

Mergers and acquisitions have been a core part of strategic management for many companies (Holliday 2015). The strategy involves buying, selling and dividing different companies for purposes of market growth, or to gain competitive advantages, without necessarily creating a third enterprise (Bruner 2004). Although M&A deals became popular in the 19th century, they are as old as corporate history. Corporate history literatures show that M&As started as early as 1708 when the East India company merged with one of its competitors as a competitive strategy to outwit its rivals in the Indian market (Ernst & Young 2004). European-specific corporate literatures show that among the earliest M&A agreements started in the late 1700s when Italian banks merged as part of a grand corporate finance and management dealing between Monte dei Paschi and Monte Pio banks (Glenlake Publishing Company 2000). The trend towards mergers and acquisitions has built up in recent years, with financial and economic experts recording the biggest M&A deals in the last century (Ruback 2002). For example, the 1999 Vodafone AirTouch’s acquisition of Mannesmann AG was valued at more than $200 billion (Holliday 2015).

Other major M&A deals include American Online acquisition of Time Warner, which was valued at more than $180 billion, the 2007 RBS’ acquisition of ABN-AMRO, which valued at more than $90 billion, and the 2008 Altria’s acquisition of Philip Morris International, which was valued at $113bn (Holliday 2015). Many more M&A deals have characterized the global economic space. However, their continued increase in value and numbers show that many companies are choosing this strategic approach in the wake of today’s fast-paced and competitive business environment (Koller & Goedhart 2005). This phenomenon is especially true in the luxury brand market (Ait-Sahalia & Parker 2004). This chapter analyzes previous research studies that have focused on exploring M&A transactions in the global corporate space and more specifically in the luxury brand industry. It explores several issues relating to the research questions, including understanding the motives for pursuing mergers and acquisitions, finding out the value creation associated with M&A transactions, and investigating the types of synergies enjoyed by luxury goods companies when pursuing the M&A strategy.

Motives for Mergers and Acquisitions

The motives for engaging in mergers and acquisitions are many. Indeed, different companies have different motivates for participating in such transactions (Bruner 2004). According to, BUSMAN (2014) these motives depend on the nature of their businesses and the objectives they want to achieve in their corporate plan. Alternatively, Straub (2007) says that the motives for engaging in mergers and acquisitions could be classified into two categories. The first category is neoclassical motives, which refer to the desire by companies to maximize their shareholder’s wealth by creating synergies. The second category is behavioral motives, which strive to improve managerial efficiencies as opposed to increasing shareholder wealth (Straub 2007). In a related set of literature, DePamphilis (2010) says that the motives for engaging in M&A transactions may include synergies, hubris and agency motives. Researchers such as Sherman (2011) and Swanson (2014) adopt a different perspective of this issue by analyzing M&A transactions from three perspectives – choice, process, and macroeconomic perspectives.

A rational understanding of the motives for pursuing mergers and acquisitions would argue that most companies adopt this strategy to maximize shareholder value or to improve managerial efficiency (BUSMAN 2014). The rational choice theory also states that M&A transactions could help to transfer wealth to customers and companies. The monopoly theory also supports this view (Wolff 2008). According to both theories, customers could reap economic benefits from M&A transactions because they would benefit from market consolidation and reduced competitive pressures (Carrington 2008). The nature of certain mergers offers this benefit automatically. For example, conglomerate mergers and horizontal mergers offer this benefit by reducing the number of entrants in the market (Fee & Thomas 2004). Such mergers also create huge barriers to entry, thereby allowing dominant players to reap from their dominant positions. Cross-product subsidies are also notable benefits that are associated with such mergers (Vadapalli 2007). Acquisitions made within the same industry also result in such advantages. Relative to this fact, the rational choice perspective also reveals that scalability advantages are other motives for pursuing M&A transactions (Orlovic 2003). The raider theory adds to this analysis by proposing that M&A transactions could generate shareholder value by transferring it from target shareholders through greenmailing or alternative techniques (Orlovic 2003).

Investment and valuation theories have supported the principles of the rational choice theory because they share the same premise for understanding M&A motives (BUSMAN 2014). These theories show that some companies engage in M&A transactions because of the net gains they would get from using confidential information. These theories hold that such private information yield value because firm managers are usually aware of important company information concerning targeted companies that they could use to create value for themselves (Glenlake Publishing Company 2000). The empire building and agency theories have further reinforced this fact because they hold that manager efficiency is a key motive for engaging in M&A transactions (Glenlake Publishing Company 2000).

Researchers have also used the efficiency theory to explain how M&A transactions maximize shareholder value. This theory maintains that these companies could realize these benefits by attaining operational, financial, and managerial synergies (Carrington 2008). Focusing on managerial synergies, Schlossberg (2008) holds a different view from many researchers who believe that most managers often adopt M&A strategies to increase their efficiency because he believes that the same managers could be motivated by non-economic factors, such as improved social profile and increased salaries, to adopt M&A strategies. This way, they would not necessarily be engaging in such strategies to increase shareholder wealth, but to meet their selfish interests. Some critics of the agency theory have highlighted this problem by saying that it emerges from the separation of ownership and management (BUSMAN 2014; Carrington 2008).

The agency theory shares a close relationship with the hubris hypothesis, which argues that, occasionally, managers make irrational corporate decisions because they are overconfident about their ability to manage an organization (Swanson 2014). For example, this problem mainly arises in acquisitions because some managers buy other companies (usually smaller companies) because they believe they can do a better job at managing them, compared to the existing managers. Wolff (2008) and BASEAK (2014) have taken a keener look at this problem. They say it occurs within the context of employment risk (Wolff 2008; BASEAK 2014). The problem emerges from the clash between managers’ personal interests and the potential for companies to grow from M&A transactions. Following this understanding, risk averse managers often prefer to engage in M&A transactions as a strategy to reduce their employment risk (Vadapalli 2007).

The Glenlake Publishing Company (2000) takes a different perspective in understanding the motivations for engaging in M&A transactions by showing that such decisions occur out of processes that involve different aspects of organizational performance. For example, it says that organizational politics, managerial capabilities, and information processing capacities often contribute towards a wider elaborate decision-making process that defines whether companies should engage in M&A transactions, or not (Glenlake Publishing Company 2000). According to proponents of the disturbance theory, macroeconomic movements often create uncertainties in the business environment, which further lead managers to change their expectations and choose whether to adopt M&A strategies as a coping mechanism, or not (Miller 2011). Such cases may lead to M&A waves if the people who do not own assets begin to believe that available assets are worth more value than their actual value or than the value perceived by the real asset owners. Following these theoretical insights, many researchers have highlighted the following factors as the main motivations for engaging in M&A activities.

Defensive Strategy

Grossman and Hart (1980) argue that different companies engage in M&A transactions as a defensive corporate strategy to minimize the possibility of a hostile takeover. For example, there is enough evidence showing that some companies often engage in M&A activities to increase their size and intimidate other firms from thinking about acquiring them. For example, the proposed merger between LVMH and its French rival, Hemes, highlights this fact. LVMH has consistently engaged in negotiations to merge, or acquire, the French company, but it has failed to do so (Guardian News 2015). It first started by buying non-controlling shares in Hemes, with the hope that it would eventually hold a majority stake. However, Hemes has been unimpressed by LVMH’s overtures and instead created a holding company, which owns 51% of the company’s stocks to make sure that LVMH does not successfully buy it out (Guardian News 2015). This example shows how some companies may be defensive about the M&A strategy. Alongside the same continuum of defensive corporate strategies, some companies also prefer to engage in M&A deals to prevent rival firms from consolidating their market positions (DeLong 2001). Similarly, they may do so if they want to minimize the possibility of a takeover by a third party.

Increasing Control

According to McLean (2002), some firms engage in M&A strategies as way of increasing control of their operations, or in their primary markets. This motivation often emerges because M&A strategies often allow participating firms to internalize their upstream and downstream operations (Kapferer 2012). This way, the firms have better control of their value chains. The result is that these organizations reap the benefits of lower transaction and information costs (Kapferer 2012).

Regulatory Reasons

Changes in the legal environment also act as a motivation for companies to engage in M&A activities. Particularly, increased deregulation of the business environment presents an opportunity for firms to improve their competitive edges through M&A. The same deregulated legal environment allows firms to enjoy lower tax liabilities (Orlovic 2003).

Access to New Resources

M&A strategies often allow companies to access new resources that they would have otherwise not had if they decided to operate alone (Teixeira 2011). This motivation derives its merit from the commonly known phrase “two is better than one.” Participating firms could enjoy a wide variety of resources, including technology, patents, and superior management (among other factors). Closely associated with this motivation is the potential for participating firms to diversify their operations through mergers and acquisitions (McLean 2002). For example, Dash (2010) says, M&A activities allow participating firms to increase their products and expand their product lines. Many luxury brands, such as LVMH, commonly use this advantage (Miller 2011). Similarly, the same advantage allows them to access new geographical areas and markets, which may further improve their bottom-line and increase their profitability. This way, they could easily diversify their risks. Nonetheless, some researchers say that this strategy may not necessarily add value to the company; instead, they propose that value creation could happen through internal diversification (independently diversifying a company’s product portfolio) (BUSMAN 2014; Carrington 2008).

Access to New Markets

According to Carrington (2008), the rise in the number of M&A transactions in luxury brand segment emerges from the need for western-based luxury companies to expand their outreach to emerging markets. Particularly, there is growing interest among these companies to enter into such transactions to gain access to large and lucrative markets, such as China.

Value Creation in Mergers and Acquisitions

Value creation in M&A transactions is a long-standing topic in the analysis of M&A activities (Holliday 2015; Corominas 2014). Although many researchers have explored this issue, their views regarding the value created by M&A transactions vary. Different types of value emerge in their analysis. Key among them is shareholder wealth creation.

Shareholder Wealth

Many researchers have commonly touted shareholder wealth as a significant platform for value creation, in M&A transactions, with many analysts believing that M&A activities increase shareholder wealth (Frensch 2007; Geiger 2010; McLean 2002). Many researchers believe that value creation occurs from the maximization of shareholder wealth through M&A transactions (BUSMAN 2014). Neoclassical theorists have mainly promoted this view. To understand its factuality, Risberg (2013) believes that shareholder value could only increase if the sum outlay, after the M&A, is more than the sum outlay of the transaction before the merger or acquisition. Within the context of M&A transactions, the maximization of shareholder value supports the rational choice theory (Wolff 2008). Proponents of this theory say that value creation (in M&A activities) only occur when companies recoup their merger or acquisition costs and generate a premium above this value (Swanson 2014). According to Geiger (2010), such values could only emerge through the creation of synergies. Such synergies could similarly occur through “shared knowhow, shared tangible resources, pooled negotiation power, coordinated strategies, vertical business integration and combined business creation” (Brage 2014, p. 6).

Although many researchers argue that M&A increase shareholder wealth, some of them believe that M&A activities could decrease shareholder wealth (Geiger 2010; McLean 2002). For example, a study by Swanson (2014), which analyzed acquisitions between 1980 and 2001, revealed that many acquisitions create decreased shareholder value. Nonetheless, there was a distinction in his findings, which revealed that decreased shareholder value was more common in acquisitions that involved a large firm acquiring a small firm and not when a small firm acquires a large firm (Swanson 2014). This difference traces its roots to the agency theory because Orlovic (2003) says the agency problems that often characterize large firms lead them to make wrong decisions, which ultimately manifest in reduced shareholder value.

Nonetheless, a closer look at the stock market performance for M&A activities, which involve both small and large firms, show that they both lead to value creation (Homsud & Wasunsakul 2009). Many researchers do not explore the reasons for this outcome. Nevertheless, Hitt (2012) approaches this issue from a redistribution perspective, which questions a hypothesis proposed by some researchers that mergers and acquisitions simply involve a transfer of shareholder wealth from the acquired firm to the acquiring firm. According to Gaughan (2007), there is no empirical evidence supporting such a hypothesis. However, some analysts who support the creation of shareholder wealth as an advantage of M&A activities use it to support their positions (BUSMAN 2014; BASEAK 2014). Orlovic (2003) believes that the real gains/value of M&A activities would only emerge from the efficient management of resources to increase a company’s revenue.

Needle (2004) conducted an analysis of the 50 largest mergers and acquisitions, from 1979 to 1984, and found that most mergers and acquisitions increase asset productivity in the end. An indicator of this advantage is increased cash flow for the participating firms, compared to their peers (Ross 2015; Gaughan 2007). Based on this analysis Miller (2011) argues that M&A transactions mainly create value for the shareholders of targeted firms. This advantage emerges from the fact that targeted firms often look for short-term benefits, mainly for their shareholders, before they consent to any merger or acquisition deal (Glenlake Publishing Company 2000). Comparatively, acquiring firms look for the long-term gains in M&A transactions, without necessarily looking at how their shareholders would benefit in the short-term (Glenlake Publishing Company 2000). These long-term benefits may materialize, or not, depending on the quality of due diligence conducted by the participating firms. Relative to this discussion, Bruner (2004) concludes, “M&A clearly pay for the shareholders of target firms, while most studies on the combined result of bidder and target present a positive net value” (p. 15).

Improved Competitiveness

Increased competitiveness is an advantage enjoyed by many firms that engage in M&A transactions. This advantage is often applicable for companies that enjoy improved operational synergies from M&A activities (Hitt 2012). Mostly, companies that have complementary operations enjoy this advantage. Analysts have pointed out that vertically integrated companies are the main beneficiaries of such value creation advantages (Damodaran 2005b; Ernst & Young 2004).

Innovation

Many analysts have revealed that M&A transactions lead to technological transfers (Vadapalli 2007; Kapferer 2012). In fact, this paper has shown that this advantage is a motivation for firms to engage in M&A transactions. Particularly, it is more beneficial to small firms that enter into M&A deals with large firms because the latter could provide them with technological knowledge that they do not have. Relative to this understanding, Hitt (2012) says,

“Acquisitions that provide new knowledge to the acquiring firm that can be used to enhance its competitive position often create value. For example, the knowledge gained from acquisitions can enhance innovation when the target firm has complementary science and technology to that held in the acquiring firm” (p. 11).

Furthermore, the large firms have big research and development facilities that the small firms could use to improve their product development processes. Increased innovation is a byproduct of this process because with increased technological transfers, firms could improve their innovative activities. Increased innovation closely aligns with improved firm competitiveness as a value creation advantage in M&A transactions because firm competitiveness rides on the support of improved innovation (Kapferer 2012).

Synergies associated with M&A Types

According to Frensch (2007), synergies associated with M&A transactions often emerge from the principle that stipulates, “The sum of a whole is greater than the sum of individual parts” (p. 17). Although this principle applies to different disciplines and different research contexts, in M&A transactions, it refers to the additional value created from M&A activities (Brage 2014). This value is usually greater than the value that most firms would realize by operating alone. Independent of the M&A analysis, different researchers have unique typologies of synergies. For example, Kapferer (2012) says the main types of synergies are tax, financial, marketing and operational synergies. Others have categorized synergies into the following categories – operational, financial, managerial, and market power synergies (Brage 2014). Carrington (2008) proposes a more simplistic understanding of synergies by saying that they split into only two groups – financial and operational synergies.

Financial Synergies

Financial synergies refer to “the performance advantage of firms from leveraging financial resources across their businesses” (BUSMAN 2014, p. 38). Financial synergies often accrue from several financial operations, including tax benefits, corporate risk reduction, and economies of scale (Dash 2010). They may also arise from the increase of an internal financial pool. The portfolio theory argues that most companies, which have imperfectly correlated financial performance, are likely to experience minimal financial distress after a merger or acquisition (Ernst & Young 2004). Such transactions are also likely to minimize default costs by increasing the debt capacity of combined risks. In this regard, M&A activities increase the debt capacity of merged firms. These advantages could help companies to exploit their debt shields and leverage their improved financial positions in future corporate negotiations. A substantial risk reduction is likely to occur in such firms (Gaughan 2007).

According to Miller (2011), investors are often attracted to such companies because they provide them with an opportunity for undertaking firm-specific investments that lead to lowered cost risks. Sherman (2011) says that M&A transactions also allow participating firms to account for their profit and losses more effectively because the companies could use one firm’s profits to offset the losses of another. This advantage allows these companies to reduce their tax liabilities. Furthermore, companies that operate in countries that accommodate tax-deductible interest payments are bound to enjoy a financial reprieve that arises from an increase in their debt capacities (Faccio & Masulis 2005; Needle 2004). Financial synergies also accrue from increased economies of scale that arise from lower debt and equity transactions. Lowered floatation costs could also contribute to the same synergies because such costs can spread over a merged (larger) business (Ernst & Young 2004).

The increase of a firm’s internal capital reserves also helps to increase the same financial synergies because companies that enjoy such synergies also enjoy improved quality of capital allocation (Wolff 2008). Reduced financial costs and increased financial flexibility are also common advantages enjoyed by these companies. Increased financial flexibility also increases the rate of financial returns enjoyed by these companies. The merger between LVMH and the Italian luxury company, Bulgari, is an example of the quest by companies to realize financial synergy through M&A deals. Analysts said, besides, increasing LVMH’s market share, this merger increased the company’s earning potential (financial synergy) by $1billion, which the company added as additional revenue from the merger (Guardian News 2015). Through such mergers, the companies also enjoy increased liquidity, which they used to exploit existing market opportunities. Most of these luxury groups use the money they get from such M&A transactions to expand their distribution networks in emerging economies, such as China, India, and Brazil (Vadapalli 2007). They have done so with the quest to increase their market presence in these emerging markets.

Operational Synergies

Besides financial synergies, operational synergies also emerge as common types of synergies associated with M&A transactions (Sirower & Sahni 2006). Operational synergies refer to improved performance of organizational processes, including improved economies of scale, scope economies, and resource complementarities (Ernst & Young 2004). According to Teixeira (2011), operational synergies often arise from several factors, common being the spread of factors of production and overhead costs. Such synergies may also occur from expanded geographical markets that emerge when two or more companies merge. In such situations, companies could leverage their fixed costs, such as marketing, warehousing and distribution costs, in expansive geographical markets thereby maintaining low operational costs, even as they increase their geographical outreach (Teixeira 2011).

This way, they enjoy reduced operational costs and increased operational synergies. Scope economies are closely associated with these operational efficiencies because they emerge when two or more companies enjoy reduced operational costs, associated with decreased production and selling costs (Kapferer 2012). Economies of scale often emerge when companies share research and development (R&D) costs or distribution costs. Similarly, such benefits may emerge from the use of a common brand that subdivides into several independent products (Kapferer 2012). Such advantages often lead to increased profits and revenues as opposed to reduced operational costs. According to Vadapalli (2007), other sources of operational synergies include “team work, waste reduction, team-building, superior production scheduling, and quality improvement” (p. 19).

Managerial Synergies

Brage (2014) says that although different literatures do not acknowledge managerial synergies as a common advantage in M&A transactions, they are difficult to ignore in today’s business world where companies strive to outdo one another based on their managerial competencies. This synergy often emerges when companies leverage their management capabilities after merging or after acquiring new firms (Miller 2011). The synergies may manifest in different forms, mostly through superior functional and design capabilities. Similarly, they may manifest through improved strategic competencies, improved leadership styles, and enhanced management systems. According to BASEAK (2014), these advantages often result in improved decision-making systems in an organization.

Summary

Mergers and acquisitions are important strategic choices for different types of companies to overcome some of their inherent operational and financial challenges. This chapter has shown that some of the world’s notable luxury brands, such as LVMH have used this strategy as a competitive strategy and as a market expansion strategy. Independent researchers, cited in this chapter, have also pointed out that these companies stand to benefit from operational and financial synergies after adopting the M&A strategy. Value creation advantages have also emerged as a key consideration for most companies to pursue in the M&A plan because companies have benefitted from increased shareholder wealth (albeit contentious), improved technological and innovation capabilities, and improved competitiveness. Although most of the findings represented above strive to ascertain the value creation associated with M&A transactions, most of the post-merger performance of participating firms do not necessarily trace to M&A transactions (Straub 2007).

For example, the market can react negatively to a company’s internal growth opportunities and lead to negative M&A outcomes (Hitt 2012). These outcomes could easily lead to a negative reporting of M&A activity, even though firms may be enjoying a positive net present value. Ernst & Young (2004) has further explored this issue and suggested that the mode of M&A payment could similarly affect the outcome of M&A activity. For example, it posits that cash and stock payments could have different effects on M&A (Ernst & Young 2004). Bruner (2004) adds that most mergers and acquisitions paid for in cash have a better positive outcome on the participating firms, compared to those that involve stock payments. Based on the insights highlighted in this section, Hitt (2012) and Damodaran (2005a) summarize the possible reasons for the failure of M&A to create value to include the inability of firms to create synergy and paying high premiums in M&A transactions.

Miller (2011) adds to this list of possible causes of M&A failure to include the failure of organizations to carry out an effective and efficient integration process and the selection of inappropriate targets for mergers or acquisitions. Conversely, the opposite is true because strategically selecting M&A targets and undertaking a successful integration process could easily create synergies and lead to the creation of M&A value (Bruner 2004). These insights show that although different companies could benefit from different forms of value creation in M&A transactions, they need to be wary of the factors that could lead to a decrease in these values (Bruner 2004). Nevertheless, there is a need to undertake more research to understand these transactions and possibly recommend new opportunities for improving value creation opportunities in them.

Methodology

Introduction

This chapter outlines the processes and techniques used to collect research information for purposes of answering the research questions. Some of the main elements outlining this chapter include the research approach, research design, data collection technique, and data analysis techniques. This chapter also contains information revealing how the researcher maintained high standards of validity and reliability throughout the data collection and analysis processes. Collectively, these elements of the research process appear below

Research Philosophy

The aim of this study is to understand the reasons why luxury brands choose the merger and acquisition strategy. The research objectives seek to understand the main motives for pursuing mergers and acquisitions, strive to explain how luxury groups choose the M&A strategy, want to understand the synergies associated with M&A strategies and seek to understand the value creation opportunities that luxury brands stand to enjoy from pursuing the M&A strategy. To meet these research objectives, this paper adopted the post-positivist research philosophy, which involved measuring observable facts and phenomena (Dover 2013). According to Bernard (2011), measuring observable facts and phenomena are key considerations in the post-positivist school of thought. To come up with relevant information and statistics that could help in answering the research questions, this paper also adopted the event study method, which analyzes the financial performance of LVMH before and after mergers and acquisitions (Dover 2013). Although the method usually uses complex mathematical equations to analyze research issues (Hosken & Simpson 2001), this paper used simple financial data, such as stock market performance and sales growth numbers, to answer the research questions.

Similarly, this paper used different accounting indicators, such as the Return on investments (ROI) and Return on Assets (ROA) to analyze the performance of LVMH, viz-a-viz its M&A strategies. Comprehensively, the research philosophy underlying this study adopted the use of mathematical equations and logic to answer the research questions. These processes involve the use of positivist measurement tools. Combined with the use of the quantitative research design, the processes underlying this study premised on empirical analyses. Comprehensively, since the objectives of this study go a step further into analyzing intricate details of the M&A strategy, this paper delved into details surrounding the intricate motivations for seeking M&A deals. Therefore, although the post-positivism research approach is usually concerned with describing the surface reality of things (Akita 2008), the structure of this paper went a step further to explain the motives and synergies associated with LVMH’s M&A quest. The focus on only one case study aligned with recommendations by proponents of the post-positivism approach to use only one case study for purposes of research analysis (Dover 2013). The single case study provided an opportunity to undertake incisive analysis of the research issues and understand patterns that would openly help to understand the research phenomenon (Dawson 2002). Consequently, the philosophy (post-positivist philosophy) underlying this study aligned with the nature of the study.

Research Approach

Based on the research aim and objectives of this study, this paper does not simply describe M&A transactions in the luxury segment, but goes a step further to investigate the motivates why luxury groups pursue this strategy, which types of synergies they enjoy and the value creation advantages present in such transactions. Based on these processes and insights, this study is not descriptive, but explanatory. The mixed methods research approach was appropriate for this paper because the study used qualitative and quantitative metrics to answer the research questions. For example, to justify the use of the quantitative research method, this paper used numerical measures of analysis to explain the research issues. Similarly, to support the use of qualitative research measures, this paper used behavioral theories (such as managerial attitudes towards M&A) to explain the motives for pursuing M&A strategies. Furthermore, the use of the mixed methods research approach was justifiable because some of the research questions required a qualitative assessment, while others required a quantitative assessment. For example, understanding the value creation associated with M&A transactions requires a quantitative understanding, while understanding the motives of LVMH to engage in M&A transactions required a qualitative assessment.

Research Strategy

Although many luxury brands have participated in M&A strategies, this paper only focused on the LVMH case. The single case approach justifies the use of the case study approach as the main research design. The focus on a single case helped the researcher to undertake an in-depth analysis of the research phenomenon (Tracy 2012). The use of the case study research design was also justified because it can answer “why” and “how” questions. This study contained both types of questions. For example, understanding the motives for engaging in M&A is a “why” question, while investigating the different types of synergies enjoyed by LVMH by participating in M&A is a “how” question. The case study analysis provided the justification for using an inductive approach in the study, because the paper makes broad generalizations from one case. Comparatively, the deductive reasoning tests hypotheses and helps researchers to reach a logical conclusion of a research issues. There were no hypotheses in this paper.

Data Collection

The main sources of data used in this study were secondary research materials. Mainly, the paper used information from books and credible websites that explored M&A transactions globally and in the luxury brand segment. However, the researcher supplemented the information received from journals. The main types of information obtained from the books included research information regarding the motives of pursuing mergers and acquisitions in the global corporate space and in the luxury brand segment. Information sought from this literature source also included the types of value created through M&A transactions. Credible websites were instrumental in providing information relating to company financial performance and managerial attitudes towards M&A transactions. To make sure that the information received through this research source was credible, the paper included research information from institutional websites. Unlike primary research that often consumes a lot of time, the secondary research process was easy to carry out because it was less costly and convenient to do. This advantage helped the researcher to focus on more substantive areas of the research process, such as data analysis (Liu & Nissim 2000). Furthermore, considering most of the information used in this paper is available online, it was easy to undertake comparative evaluations of available findings.

Data Analysis

The content analysis method provided the main framework for analyzing available research data in this study. As its name suggests, the content analysis method is instrumental in evaluating the contents of varied research materials in the context of the research phenomenon (Schreier 2012). Motivated by the intention to make inferences from the research materials to the context of the research phenomenon, the researcher applied its competencies to the study. To answer the research questions and to make inferences regarding the subject of interest, the content analysis method was mostly instrumental in evaluating research information that the researcher developed though the event analysis method (Krippendorff 2012).

For example, to find out the value creation potential associated with M&A transactions in the luxury brand sector, the content analysis method helped to compare the post-merger financial performance of LVMH with the its pre-merger financial performance. A positive net gain meant that value creation was apparent. Similarly, a negative net loss in value mean there was no value creation potential in the M&A agreement. Similarly, a comparison of financial metrics data, such as the ROA, was instrumental in knowing who benefitted most from value creation. For example, a net increase in LVMH’s share price showed that its shareholders were the biggest beneficiaries of the M&A transactions.

Comprehensively, the content analysis method was appropriate for this paper because it offered the researcher several advantages in the data analysis process (West 2012). In this regard, the content analysis method offered the researcher with an easy and convenient way of undertaking the research process. Similarly, it required little time and resources to undertake the data analysis process. Furthermore, there was little possibility of bias in the research because unlike other human-based data analysis methods, there was minimal involvement of the researcher in the study.

Reliability and Validity

The reliability of this study depended on the extent that the views of the authors sampled in this paper merged or diverged on the issues investigated in this paper. Particularly, the researcher strived to investigate the areas of convergence or divergence concerning their views on value creation and synergy creation. This paper also included the test-retest reliability standard by comparing information from past and recent studies. For example, to evaluate the consistency of studies sampled in this paper, the researcher compared the results of previous studies and this paper’s results. The aim of the process was to find out if there were areas of divergence or convergence, especially with regard to M&A transactions that occurred in the past and those that occur today. The researcher measured validity from analyzing the findings of different tests conducted on the same set of data.

Summary

This chapter has outlined the different steps followed to answer the research question and to meet the research objectives. The philosophical framework of this study stemmed from the post-positivism philosophy. Here, the researcher’s focus was on investigating the underlying mechanisms of the research issue. Indeed, since this paper goes a step further than describing the main motives for adopting M&A strategies in the luxury brand sector, it suffices as an explanatory paper. To answer the different types of research questions presented in this study, this researcher used the mixed methods research approach. Using a case study design also helped to undertake an in-depth research of the research phenomenon and the research questions. The researcher analyzed information obtained from journals, books, and credible online websites using the content analysis method because it helped to make inferences from the literatures sampled to the content of the study’s analysis. Lastly, this chapter reveals that there were deliberate efforts by the researcher to make sure that the information included in the study was reliable and valid. To do so, the researcher checked for consistency in the study’s findings.

Findings and Analysis

Introduction

The integrative literature review showed that uncertain regulations, market volatilities, and limited funding challenges have characterized today’s fast-paced and globalized world. These issues have made M&A transactions more complex and trickier, for businesses that want to reap their benefits, compared to past years (The American Graduate School of International Management 2013). The characteristics of the luxury brand segment have further compounded these complexities because the fast-paced nature of product lifecycle development and style complexities in this industry have made it difficult for fashion brands to openly merge or accept acquisition agreements (Firm News 2015).

The LVMH Case

Based on the last 21 years of LVMH’s operations, the company has consistently established itself as a leader in the adoption of the M&A strategy, within the luxury brand sector (The American Graduate School of International Management 2013). For example, in the past two decades, the company has acquired several brands, including “haute-couture houses Christian Dior and Givenchy, as well as luxury champagne grandes marques such as Dom Pérignon and Krug, and fashion labels Donna Karan, Céline and Marc Jacobs” (The American Graduate School of International Management 2013, p. 5). This strategy has put the CEO of LVMH at the helm of the world’s largest luxury goods brand. Analysts say the company’s M&A strategy is the main driver for the company’s high sales (Vadapalli 2007; Roberts 2013). In 2014, it reported a profit of $5 billion. This was a 19% increase compared to the previous year (Guardian News 2015). This growth has manifested in different competencies enjoyed by the company’s shareholders. A key objective of this study was striving to understand these competencies through an analysis of how M&A has created value for the company.

Value Creation

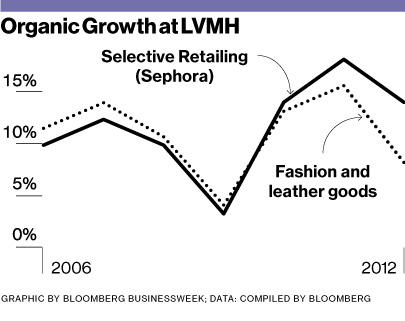

According to Roberts (2013), the potential for market growth in many mainstream Asian markets explains LVMH’s growth strategy. Its current engagements in these markets have made LVMH flush with cash, which has made it eager to offload it through organic growth and strategic M&A transactions. According to Wolff (2008), the company has expanded its number of stores in most of its main Asian markets, except for Japan where it has maintained a steady number of 320 stores. Currently, few researchers explain why it has had a static growth in Japan. However, the company has added more than 130 stores in other markets (Stevenson 2011). Comparatively, it added 165 stores in the previous year, 2012. Sherman (2011) says that LVMH should pursue M&A deals in China because this is the biggest emerging market in the world. Particularly, the Asian giant poses a huge market potential for LVMH’s wines and spirits. LVMH’s M&A plan, which has spanned several decades, has partially complemented the market potential for LVMH. The following diagram shows the company’s organic growth trajectory in the last decade (stemming from its M&A plan)

According to the graph above, the fashion and leather segments of the company reported the lowest growth. This means that other luxury segments, such as clothing, perfumes, wines and spirits reported better sales during the same period. However, the fashion and leather segment shares the same growth pattern with other segments of LVMH’s portfolio. The dip in growth numbers reported after 2006 signifies the slump in the global economy during the 2007/2008 global economic crisis (Lamb 2011). Luxury brands were among the hardest hit products during this recession (Stevenson 2011). Therefore, the dip was not only unique to LVMH (Lamb 2011). Indeed, it does not negate the fact that the company has consistently created value for its shareholders. The following diagram also shows how the company has created value for its customers through an increased share growth trajectory

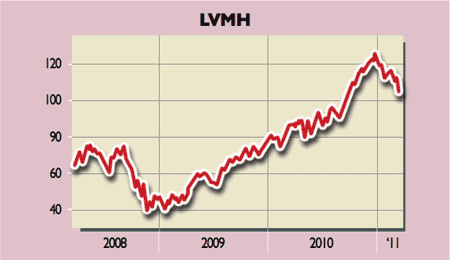

According to the graph above, LVMH has reported a strong growth in its share price numbers, since 2007. Again, the slump noted after 2008 traces to the aftermath of the global economic crisis. However, since the global economy is on a recovery path, the company’s share prices have revamped. A full description of the company’s financial performance appears in appendix one.

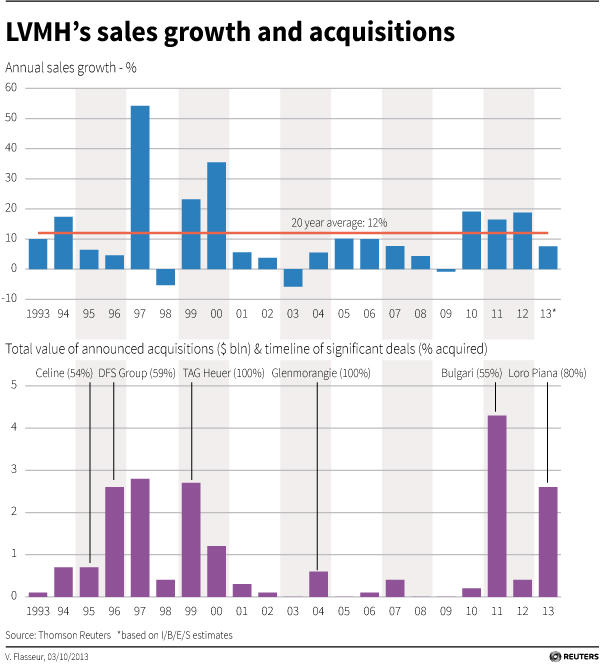

There is a direct correlation between LVMH’s strong company growth and its M&A deals. For example, the company reported increased sales figures during periods of increased M&A activity. The following graphs show this fact

According to the above diagram, the pattern of total value of announced acquisitions from 1993 to 2013 mirror the pattern of sales growth during the same period. Comprehensively, the two graphs show that periods of increased M&A activity heralded periods of increased sales growth. Conversely, it is correct to deduce that M&A transactions were responsible for increased sales numbers. LVMH created shareholder wealth this way.

Motivations for Engaging in M&A transactions

Expansion of Markets

The history of LVMH litters with opportunistic mergers and acquisitions by the company’s CEO (Valtsev 2014; Roberts 2013). Since 1990, when Mr. Arnault assumed the helm of the company, LVMH has expanded its operations into many overseas markets, making it among the world’s largest luxury brand companies (Glenlake Publishing Company 2000). Indeed, through its M&A strategy, LVMH has grown its five business divisions to include “wines and spirits, fashion and leather goods, perfumes and cosmetics, watches and jewelry, and selective retailing” (The American Graduate School of International Management 2013, p. 6). Through this expansion strategy, LVMH has more than 50 products under its umbrella. The company acquired many prestigious brands under its banner, such as Givenchy and Kenzo, through M&A (Valtsev 2014).

These acquisitions refer to mergers and acquisitions that occurred in LVMH’s fragrance and cosmetic segment (Bruner 2004). They highlight the company’s pursuit of market expansion as a motivation in M&A. Christian Dior, Guerlain, Givenchy, and Kenzo are some of the most notable brands owned by LVMH in the fragrance and cosmetic segments. However, within the last two decades, the company has acquired other brands, such as Bliss, Hard Candy, and Urban decay among others through the same M&A plan (The American Graduate School of International Management 2013). According to Miller (2011), LVMH acquired these brands to expand its market to appeal to younger markets. For example, although the fragrance and cosmetics industry has mainly had a strong appeal in Europe, LVMH has acquired new brands, in the same sector, in the US, to penetrate the North American market (Stevenson 2011). Collectively, these insights show that market expansion was a significant motivator of LVMH to engage in M&A activities.

Expanding its Business Model

LVMH has used its M&A strategy to expand its business model. So far, the company has specialized in five lines of business, which include, wines and spirits, fashion and leather goods, perfumes and cosmetics, watches and jewelry, and selective retailing (BASEAK 2014). Its M&A strategy has helped it to expand its business model beyond these five categories (Valtsev 2014). Particularly, LVMH’s venture into auction houses, which sell antiques and art, is a new line of business for the company. It ventured into this new line of business by acquiring Philips in a $60 million deal, in 1990 (The American Graduate School of International Management 2013). Subsequently, it acquired Geneva-based gallery, de Pury through the same strategy. At the same time, it acquired Parisian auction house, L’Etude Tajan in the same way (BASEAK 2014).

These acquisitions helped to expand the company’s involvement in the collection of home artistic products (Glenlake Publishing Company 2000). In the same fashion, it further expanded its art collection to include automotive products by acquiring Bonham and Brooks (a top automotive company in Europe). According to the American Graduate School of International Management (2013), the company’s CEO leveraged some of the synergies it enjoyed from its other business segments to help its new line of business succeed. For example, it says, “The CEO could use the champagne, rare wines, jewelry and fashion as well as the cachet of its parties and product launches to lure new customers. In terms of synergy, it would all fit together nicely” (The American Graduate School of International Management 2013, p. 7).

Synergies Associated with M&A

The literature review segment of this paper showed that the main types of synergies in M&A transactions include financial and operational synergies.

Operational Synergies

LVMH has constantly enjoyed these synergies through its cross-border M&A activities (Teixeira 2011). The company’s success in the Asian market highlights this fact. For example, the fashion and leather goods sector has benefitted from increased operational synergies through M&A arrangements (Teixeira 2011). This sector accounts for 30% of the group’s total revenue. Most of this income comes from the company’s operations in the Asian-pacific markets, mostly Japan (Gaughan 2007). Its success partly stems from the increased operational synergies that the company enjoys through unique mergers and acquisitions within the sector (Mulherin & Boone 2000). For example, Valtsev (2014) says LVMH’s success in Japan stems from unique M&A agreements that have fortified its presence in the market. It has replicated the same success in Europe through mergers with Italian leather designer, Leather Karan (Hitt 2012). In the US, the company has merged with Prada and enjoyed improved operational synergies, especially in product development and distribution. Its M&A strategy also accounts for the rise of Louis Vuitton as a leading leather product, in not only Europe or Asia, but around the world as well.

The success of this product and other similar brands within the fashion and leather goods sector shows the capacity of LVMH to leverage its synergies in the market (Frensch 2007). To support these findings, Hitt (2012) gives an example of its Kenzo production plant, which LVMH turned into a logistics facility. The facility mainly focuses on organizing logistics for the production and distribution of men’s products. Givenchy and Christian Lacroix are some brands that use this facility (Glenlake Publishing Company 2000). As part of its larger plan to exploit operational synergies, LVMH also acquired new brands in the US fashion and cosmetics segment. This strategy helped it to leverage its R&D synergies across different brands within the same segment. This advantage was mainly vivid in the company’s operations within the US and Europe.

Relative to this discussion, the American Graduate School of International Management (2013) says, while LVMH’s R&D expenditure was similar to most firms in the industry, it generated a higher growth rate than its peers within the fashion and cosmetics segment. In fact, LVMH hoped that its R&D competencies would help to increase the sales of the acquired brands. This prediction happened. Relative to this discussion, the American Graduate School of International Management (2013) adds, “As part of the company’s drive to consolidate margins in this division, the company had been integrating R&D, production, distribution, sourcing and other back office operations across brands” (p. 8). LVMH benefitted from these operational synergies because, for example, its raw material costs decreased by 20% (Teixeira 2011). Analysts also believe that the company’s fragrance section benefitted from the spillover effects of branding LVMH products under one banner. Particularly, the company’s brands were associated with LVMH’s ready-to-wear product segment, which was “cash cow” for the company (Frensch 2007).

LVMH’s operational synergies also emerged in the company’s watches and jewelry segment (Dover 2013). Some notable brands within this category include Tag Heuer, Ebvel and Zenith. An attempt by the company to increase its portfolio, in 2000, through the acquisition of new brands only added 5% to its sales numbers (Brage 2014). Its rivals, such as Richernmont and Hemes, had better fortunes in this segment because customers perceived their products as more upscale. However, LVMH leveraged its operational synergies in the manufacturing sector to outwit its competition and even eventually acquired a rival in this sector – Bulgari (Valtsev 2014). Part of the operational synergy came from leveraging Tag Heuer’s expertise in retail distribution (Roberts 2013). These strategies helped to minimize competition in this sector

Financial Synergies

The luxury brand segment has mainly suffered from poor sales in the ready-to-wear market segment (Roberts 2013). However, LVMH has been able to leverage its cost savings and maintain profitability in the wake of poor sales. The Louis Vuitton brand has merged with the larger financial capabilities of the LVMH group to create a formidable brand that has helped the company to expand its product line and improve its sales numbers, at the same time. Comprehensively, many financial experts say that they would have better financial perceptions of small brands if they were part of a larger parent company, such as LVMH (Ernst & Young 2004).

Summary

This chapter has shown the main motivations for LVMH to pursue the M&A strategy. In line with the research objectives, it has also shown the value creation advantages for LVMH’s M&A deals and the synergies it has enjoyed from pursuing such strategic choices. The expansion of geographical markets emerged as the strongest reason for the pursuit of the M&A strategy. Business model expansion emerged as a secondary motive for engaging in such deals. Similarly, financial synergies emerged as a secondary synergy, created through M&A deals, because the primary synergy enjoyed by LVMH was operational synergies. LVMH’s deals have mainly created value for their shareholders through increased share prices and increased sales numbers. These insights show that M&A activities have largely underpinned the company’s success.

Analysis and Discussion

This chapter combines the study’s findings with the findings of the literature review section. Since this study adopts an inductive approach, we extrapolate the findings of the LVMH case study to the wider luxury market segment.

How Luxury Brands Choose the M&A Strategy

Different researchers have advanced different reasons explaining why companies choose to adopt M&A strategies. So far, the literature review has shown that the different types of synergies associated with M&A transactions motivate most companies. They include financial synergies and operational synergies. The literature review also showed that other reasons why companies engage in M&A strategies include expanding their geographical markets and improved brand recognition. Although these insights are true for most companies, they represent a general understanding of the reasons many companies would engage in M&A transactions. Most of these reasons do not apply to luxury brands because of the characteristic of the industry. For example, the case study revealed that the financial synergies or operational efficiencies associated with M&A transactions may not always force luxury brands to adopt M&A, instead, cultural and non-monetary factors influence their decision to merge. The proposed merger between LVMH and its French rival, Hemes highlights this fact.

LVMH has consistently engaged in negotiations to merge or acquire the French company, but it has failed to do so. It first executed its control plan by buying non-controlling shares in Hemes with the hope that it would eventually hold a majority stake (BASEAK 2014). However, Hemes was unimpressed by LVMH’s overtures and instead created a holding company, which owns 51% of the company’s stocks, to make sure that LVMH does not successfully buy it out (BASEAK 2014). Despite this rejection, LVMH has remained optimistic that the family-owned business would eventually accept an M&A agreement (Valtsev 2014). This is why the company’s CEO, Arnault, recently said in an interview “I hope that this partnership [with Bulgari] will demonstrate that some families are able to understand the meaning of a merger with LVMH” (Guardian News 2015, p. 6). LVMH has even gone a step further to reassure opponents of the deal that the company is a peaceful shareholder. Nonetheless, these arguments have not had any significant impact on the unwillingness of Hemes to enter into an M&A agreement with LVMH. In fact, recently, reporters quoted the company’s CEO saying,

“We do not want to be a part of this financial world, which is ruining companies and dealing with people like they are goods or raw materials. It is not a financial fight, because we would lose that. It is a cultural fight” (Guardian News 2015, p. 9).

Nonetheless, as history shows, LVMH is not a stranger to controversy when it comes to M&A transactions. In fact, the 1999 pursuit of the failed Gucci merger showed that the company could go to extreme lengths to secure an M&A deal (Valtsev 2014). Particularly, the company’s CEO has a reputation for “pouncing” on struggling companies by acquiring them through M&A deals (The American Graduate School of International Management 2013). Therefore, the aggressive nature of LVMH mirrors the aggressiveness of the company’s CEO. This fact manifests through the rise of Arnault as the company’s CEO. Relative to this understanding, the Guardian News (2015) said, “In his own accession to the throne at LVMH, Arnault punched his way to the top in an acrimonious battle involving Henry Racamier, president of the Louis Vuitton business, and Alain Chevalier, the chief of the Moët Hennessy operation” (p. 9). Nonetheless, comprehensively, the failed merger between LVMH and Hemes shows that although the company may have the financial power, will, technical expertise and market advantages over its competitors, some luxury brands still consider cultural factors as a significant influence of their decision to merge or not. Besides cultural factors, some luxury brands would consider how M&A influence their value chain processes before participating in M&A deals.

Value-Chain Integration

The role played by value chain processes in informing companies’ decisions to merge or not traces its root to some fashion experts who believe that luxury brands have to maintain strict control over most aspects of their product development lifecycle because their brand reputation (particularly, the quality of their brands) depends on this fact (Kapferer 2012; Bruner 2004). Therefore, they have to maintain strict controls of different aspects of their product development processes, including sourcing raw materials, manufacturing, marketing and distribution processes because these aspects of their operations influence the quality and reputation of their brands (Kapferer 2012).

Based on this consideration, Glenlake Publishing Company (2000) reveals that most M&A activities in the luxury brand segment occur in the form of vertical integration. The main motivation of doing so is to get access to top suppliers and technical expertise that would allow struggling luxury brands to improve their brand image. Vertical integration gives them this opportunity. Efforts by established foot and handbag luxury brands to buy controlling stakes in leather and tanning development companies emphasize this fact because by doing so, they ensure the control of key raw materials. Established jewelry brands have also joined the fray by buying controlling stakes in mining companies because of the need to maintain control of their value chain. According to Schlossberg (2008), such efforts have highlighted the importance of the “mine to market” concept in the luxury jewelry market.

Conversely, luxury brands are engaging in M&A agreements to control their point of sale activities. Relative to this finding, Swanson (2014) says, “Luxury brands looking to establish a presence in emerging markets are looking for joint-ventures or partnerships with local distributors to ensure that the brand is able to maintain a certain level of control over retail operations” (p. 3). Based on the same insights, DePamphilis (2010) says luxury brands are participating in M&A agreements to indulge further in the growing trend towards the e-commerce retail segment. Particularly, this trend has increased the volume of M&A transactions between luxury brand companies and experts in the e-commerce space.

The Globalization of Luxury Brands

This paper has already shown that M&A activities increase the geographical markets for participating firms. The globalization of luxury brands has forced many luxury brands to pursue the M&A strategy because it would expand their geographical outreach, in tandem with the quest to push their brands, globally (Rough & Polished 2011). For example, LVMH has pursued this strategy to expand its market outreach in Asian and Middle East markets. So far, this strategy has yielded increased profits, as could be seen through the increased interest by private equity players to invest in the company (The American Graduate School of International Management 2013).

Indeed, Carrington (2008) says many emerging market financial groups are investing in established global luxury brands because of their perceived success in emerging markets. Many western-based luxury brands are accepting such investments because it increases their profile in the emerging markets and supports their brand growth strategy. Relative to this discussion, Swanson (2014) affirms, “Conversely, established European private equity firms are looking to focus their funds on aspirational Asian brands, particularly in China and India, with a view of helping smaller, local luxury brands grow into global luxury labels” (p. 2). The involvement of private equity firms in the global luxury brand segment has not only increased the profile of established brands in emerging markets, but has also provided much-needed market expertise in these markets and the financial muscle needed by these global brands to finance their expansion strategy (Graham & Harvey 2001).

Synergies Associated with M&A

The literature sampled in this paper showed that different companies pursued M&A transactions to enjoy different synergies. An analysis of M&A transactions of LVMH show that the company adopted the M&A strategy to enjoy different synergies. Although unclear about which synergies LVMH pursued, Kapferer (2014) and Straub (2007) say that the company’s expansion into different market segments of the luxury brand industry was an attempt by the company to generate different synergies. This fact explains why LVMH is one of the few luxury groups that have influenced most sectors of the luxury brand segment. According to Corominas (2014), having a large collection of global brands, in different premium brand segments was a stepping-stone for creating operational and financial synergies.

Summary

This chapter reveals that the motives for engaging in M&A transactions are subject to non-financial factors such as company culture and the corporate positioning in the M&A deal (Guardian News 2015). Unsuccessful attempts by LVMH to merge with unwilling partners highlight this fact. However, if companies do the M&A deal right, the inductive nature of this review (based on the LVMH case) shows that M&A deals could lead to value creation (Ernst & Young 2004; Frensch 2007). This chapter shows that synergy creation is the main driver for value creation.

Conclusion and Recommendation

Introduction (M&A Motives)

This study has shown that M&A is a core strategy, which is pursued by many luxury companies. Geographical market expansion emerged as the main motivator for engaging in M&A deals. In particular, the LVMH case showed that its market entry strategy in Asia hinged on the success of its M&A deals. M&A also provides an opportunity for the company to engage in new business segments. Particularly, its core ventures in its five business segments show that the M&A strategy helped it to promote its brand through new business ventures. These insights show that geographical market expansion and business model expansion are the main motives for engaging in M&A.

Why Choose M&A

Based on the insights highlighted in this paper, luxury brands choose to engage in M&A transactions because of synergy and value creation. This paper has shown that operational and financial synergies are the main motivators for LVMH and other luxury brands when pursuing the M&A strategy. Operational synergies have helped LVMH to improve its distribution and marketing activities. In particular, the access to new technology has emerged as a significant operational synergy enjoyed by LVMH. Financial synergies have also helped the French-based organization to improve its R&D processes and to improve its sales figures, thereby improving the company’s bottom-line and increasing shareholders’ wealth. In particular, this paper has shown that synergy creation and financial improvements share a close relation because synergies create value for such organizations. Therefore, the possibility of realizing increased value is low if LVMH and other luxury brands do not enjoy improved synergies. Lastly, brand promotion also emerged as a key motivator for these groups to acquire prestigious brands in different premium markets.

Value Creation – Synergy

Value creation is a key byproduct of many M&A deals (Lamb 2011). Although the second chapter of this paper showed that this issue is contentious, evidence from the LVMH case study showed that value creation occurred through increased shareholder wealth. Particularly, carefully targeted and skillfully managed M&A deals by the company have yielded increased value creation and synergy advantages for LVMH. For example, this paper has shown that the successful acquisition of reputable luxury brands, such as Chanel and Louis Vuitton, have not only created improved synergy and value creation advantages for LVMH, but also increased the brand’s profile in the luxury brand segment.

This is why LVMH group is among the most prestigious brands in this segment. Increased wealth creation and improved synergies have affirmed the views of the rational choice theory, which posits that M&A transactions could help to transfer wealth to shareholders and participating companies alike. These insights show that value creation often occurs through stakeholder synergy. Comprehensively, these findings contradict the views of many researchers who argue that many M&A transactions lead to the destruction, as opposed to the creation of value. Therefore, this study’s findings reveal that LVMH group mostly enjoys value creation advantages and improved synergies in M&A transactions.

What leading Academic Theories are saying about the case?

Based on the increased value creation advantages highlighted in this paper, the findings of this paper enforce the rational choice theory, which says that M&A transactions could help to transfer wealth to companies and customers. Increased shareholder wealth for LVMH’s shareholders affirms this fact. The monopoly theory also supports this fact because LVMH’s shareholders have reaped economic benefits from M&A transactions because they have benefitted from market consolidation and reduced competitive pressures (Fernandez 2007).

Recommendations

This paper has already shown that LVMH enjoys specific synergies and value creation advantages by adopting the M&A strategy. These benefits will only suffice if the company makes sure that total cost for M&A and the value of the synergy is more than the acquisition costs of new companies (Kaplan 2000). This is the only way that the company will realize capital growth and create shareholder value. Similarly, to minimize the possibility of loss in M&A transactions, it is pertinent for LVMH to effectively implement its acquisition strategy, failure to which the company may report shareholder wealth losses (Stahl & Mendenhall 2005). For example, acquiring new companies may force LVMH to make new HR changes. Therefore, it is up to the HR department to change its processes to align with the new M&A objectives.

LVMH and other luxury brands should also learn that the realization of M&A objectives depends on effective teamwork across all organizational departments. For example, Mitschreiben (2006) says the quality of coordination between the finance, personnel and business units would dictate the success or failure of M&A processes. LVMH should also understand that rapidness in M&A counts because the creation of M&A value depends on the fast creation of M&A synergies (Cigola & Peccati 2003). Stated differently, synergy creation depends on how well the company plans the integration process. Ideally, integration planning should happen when the company is undertaking its due diligence process for M&A. In this plan, the company should have a plan for overcoming communication barriers, personnel issues, change management processes, and any other barrier that may affect M&A implementation. Collectively, these recommendations would improve the odds of realizing increased synergies and value creation through increased capital growth.

General Limitations of the Study

The main limitation of this study stems from the case study research design. The focus on the LVMH case shows that the study’s findings mainly apply to this firm. Yin (2009) defines this limitation as a construct validity problem because its reliability and replicability is limited (mostly to the firm and to the wider luxury brand segment). Furthermore, the broader theoretical premises used in this paper apply to the luxury market segment. The absence of systematic procedures in conducting this research was also a limitation for this paper because, as Seawright and Gerring (2008) sees, the relative absence of a methodological guideline in case study designs is a concern for such studies. Similarly, Harvey and Brecher (2002) suggest that, “The use of the case study absolves the author from any kind of methodological considerations. Case studies have become in many cases a synonym for freeform research where anything goes” (p. 4). Some researchers explain this concern as the absence of methodological rigor (Farber & Gillet 2006; Verschuren 2003). However, to counter this limitation, this paper compared and contrasted the case study findings with other findings that have investigated how luxury brands adopt M&A.

Future Research

In the next few years, there are bound to be increased M&A activity in the emerging market segment. This interest is bound to emerge from the backdrop of increased demand for luxury goods in Middle East and Asia. This trend is also likely to increase the value of mergers and acquisitions in this industry because there are inadequate sellers in these markets while the demand for such goods is high (Goedhart & Koller 2010). China is going to be a frontier market in this segment. Already, growing interest from Chinese firms, such as the Chinese Fosun, shows that China wants to position itself in the middle of the growing appetite for mergers and acquisitions among western-based luxury brands in Asia. The growing interest by the Qatar Luxury Group in the M&A sector also shows the potential for the growing appetite for mergers and acquisitions in the Asian market. Nonetheless, emerging partners would be facing stiff competition from established luxury companies and brands, such as LVMH. Based on the growing potential for M&A in the Asian and Middle East markets, it is important for future researchers to investigate the impact of these M&A deals on the performance and brand development of luxury groups.

References

Ait-Sahalia, Y & Parker, J 2004, Luxury Goods and the Equity Premium’, The Journal of Finance, vol. 59, no. 1, pp. 2959-3004.

Akita, G 2008, Evaluating Evidence: A Positivist Approach to Reading Sources on Modern Japan, University of Hawaii Press, Hawaii.

BASEAK 2014. Mergers and Acquisitions in the Luxury, Fashion and Beauty Sector, Web.

Bernard, R 2011, Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, Rowman Altamira, London.

Brage, V 2014, Measuring Value Creation in M&As – A comparison between related and unrelated firms, Goteborg University, Gothenburg.