Introduction

At the start of the 1990s when the economic bubble exploded, the earlier sense of individuality amongst the majority of Japanese consumers became clattered as the idea of permanent employment busted and numerous people were fired from their jobs. This uneasy era of economic decline together with the appearance of independent-minded women, added to a collapse of traditional societal systems and the formation of a Japanese customer with preferences that varied noticeably in comparison to the bubble era.

During the previous decade, there was suppressing of lux-aholic conduct with respect to the 1980s craving. Nevertheless today, as the Consumer Confidence Index remains less than 50, customer attitude is moderately positive as the nation and its populace gradually ascend out of a downturn stage.

Additionally, as opposed to the United Arab Emirates (UAE) where fashions, cuteness, and brands are an appearance of social status, earnings coupled with refined preferences that permit consumers to differentiate themselves from the typical in Japanese fashion signify the typical Japanese (Japan Market Resource Network, 2007, pp. 2-3). The methodology used in this research project can be employed in studying the association involving women and consumption in the United Arab Emirates.

In a bid to shed light on major alterations in the connection involving women and consumption in Japan, this research paper discusses Japanese consumers, examines accessible secondary data, and discusses consumer groups. In addition, this research paper carries out an Internet study to elucidate Japanese views, mindsets, and aspirations toward fashions, cuteness, and brands. This paper reflects the varying positions and attitudes of Japanese women toward purchasing fashions, cuteness, and brands.

Moreover, this paper will disclose that concern in fashions, cuteness, and brands has decreased with time (Chadha, & Husband, 2006, pp. 56-68). However, there is plenty of proof that fashions, cuteness, and brands that uphold significance in satisfying varying consumer preferences will unsurprisingly find constant success.

In any case, during the gloomier financial period, total income for chief fashions, cuteness, and brands maintained an increasing tendency and consumer attitude continued to tilt positively. Women play a crucial role in contemporary Japanese consumption and media in term of fashions, cuteness, and brands.

Research Question

Individual value, corporate groups, and social identification influence consumption among Japanese women’s fashion, cuteness, and brands. The following research question has been formulated to satisfy the purpose and aim of this research paper: What is the relationship between women and consumption in Japan?

Purpose and aim

Japanese women have an extensive variety of fashions, cuteness, and brands and extensive launch of luxury customs by youthful women. Consequently, the aim of this research paper is to discover the association between women and consumption in Japan.

The paper as well seeks to discover the extent of the position of women in modern Japanese spending and media with respect to fashions, cuteness, and brands, which comprises luxury favourite individual and non-luxury favourite individual qualities. The range of luxury brands discussed in this research paper is limited to fashions, cuteness, and brands; nevertheless, the paper will touch on luxury brands at times.

The outcome of this research paper could assist luxury brand dealers who would want to venture into the Japanese market and those already existing in the Japanese market and desire to uphold the faithfulness of their clients. It could as well be a section of the research on global consumer conduct toward consumption of fashions, cuteness, and brands and marketing tactics in Japan.

Literature Review

Women consumers in Japan are unmatched in their assessment to the world’s fashions, cuteness, and brands, driving more than 40 per cent of international income in an international luxury made merchandise market whose value is estimated to be 50 billion US Dollars. Luxury branded merchandise from other countries started to change the retail setting in Japan at around the 1980s, as their accomplishment was propagated by the affluence of the intoxicatingly prosperous bubble period of the 1980s.

The shopping-stimulated women in Japan retorted to their pristine affluence in a joint “lux-aholic” binge. In Japanese community fashions, cuteness, and brands evolved from standing symbols to social systems by recognising the possessor as fitting in the bigger corporate group.

In the aforementioned social background, not embracing the matching “standing” could induce uneasiness (Tian, Bearden, & Hunter, 2001, pp. 50-66). The state of mind of the women facilitated sustenance of powerful presence of fashions, cuteness, and brands in Japan in spite of macro-economic difficulties.

Nowadays, Japanese women are rising from the refuge of the corporate group as they turn out to be progressively comfortable articulating their distinctiveness- whether via the expression of views formerly construed as excessively assertive or defiant, or through incorporating judgments that reveal personal identities. Assurance in articulating individual tastes is a revolutionary disappearance in a society where consistency has been the principle.

Japanese women are classier than ever in their consumption conduct (Nia, & Zaichkowsky, 2000, pp. 485-487). The varying consumption patterns of Japanese women, the shifting attitudes, and standards are vital to comprehending contemporary fashions, cuteness, and brands market in Japan. The Japanese women have a tendency of holding a stronger concern in purchasing fashions, cuteness, and brands in comparison to that of men.

The existence of women in the labour force is a motivating force because working away from home stimulates expenditure on self-consumption. On the same note, most women are holding up marriage, which is contributing to the high number of unmarried women in their thirties and above in the labour force, and thus offering those women higher amounts of disposable earnings to use on fashions, cuteness, and brands.

In the last 20 years, Japanese women have turned to defy formulaic homemaker duties with the intention of pursuing professions or even merely part-time vocations (Nia, & Zaichkowsky, 2000, pp. 488-497). Even though numerous of these posts are mainly secretarial or managerial conventionally, from the year 1997 Japanese women of between 30 and 44 years of age in the labour force have augmented by 15 per cent.

In Japan, the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication accounted that there were over 16 million women of between 20 and 49 years in the labour force, in 2007 and those of between 30 and 39 years claiming the larger portion of the aforementioned group. Amid Japanese female consumers, parasite singles constitute the highest number of voracious consumers of fashions, cuteness, and brands.

Parasite singles comprise about four million single women in the labour force of between 20 and 34 years who reside with their parents and thus do not incur rent expenses. Since they have minimal monetary responsibilities, these women use nearly 10 per cent of their yearly income on fashions, cuteness, and brands.

A research by Japan Market Resource Network (JMRN) disclosed that, conventionally, numerous younger Japanese women buy fashions, cuteness, and brands to recompense themselves for their hard work. In addition, a new female affluent class has appeared with an income of above ¥10 million ($86,597 US dollars) per annum (JMRN, 2007, pp. 4-6). The highly paid women use approximately 10 per cent of their yearly earnings on embellishment for individual and professional causes.

The Japanese women accounted using their funds on “eating out”, “luxury brands”, “trips”, and “vehicles”, with the biggest amount assigned toward condominium acquisition of approximately ¥30 million ($260,870 US dollars). Essentially, scores of these women have a tendency of spending on fashions, cuteness, and brands in a comparatively spontaneous way.

Over the years, publishers have aimed at Japanese women in the labour force and aged between 24 and 30 years with magazines (for instance, 25ans) that concentrate on fashions, cuteness, and brands. It is also appealing to note that fashion magazines aiming the unwarranted section of prosperous women of between 30 and 40 years have of late started to flourish, representing the purchasing command of this significant group (Eastman, & Iyer, 2012, pp. 80-96).

Methodology

Data Collection

This research paper used secondary data. The secondary sources used include journals, online libraries, Google scholar, books, and information from research by Japan Market Resource Network (JMRN).

Secondary data

Secondary data is helpful owing to its cost effectiveness. In addition, secondary data is employed to obtain early awareness into the study problem. This research paper gathered secondary data mostly from Google Scholar site, online libraries (for instance, EBSCOhost), books, and journals that give well-informed articles and study in accordance with women and consumption in Japan.

A different remarkable database that provided significant information is Mod’Art International Fashion Design and Management School Library (MIFDMSL), which is situated in the capital city of France, Paris.

In view of the fact that the majority of luxury fashion brands used by Japanese women trace their origin to France, this database was vital. Many of the desirable and distinguished luxury brands in the world are created in France. Moreover, Paris stands out as the world’s stylish city.

Findings and Data Analysis

Quality overrides Brand

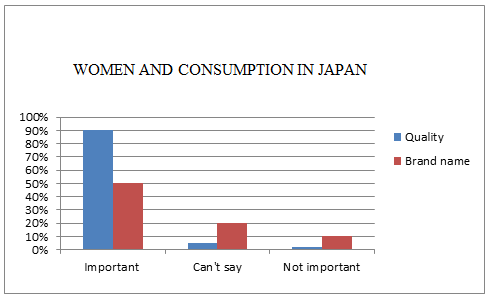

Focus groupings with Japanese women consumers permitted JMRN to comprehend insights concerning “fashions, brands, and cuteness” in a Japanese background. Particularly, the main attributes that Japanese female consumers pointed out as contributing to the consumption of a luxury brand (according to precedence) include quality, recognised brand legacy, and upholding of steady prices.

Of the total 20 interviewees (from all age brackets), several respondents sharply associated quality with the practice of purchasing and possessing a luxury brand comprising consumer service as well as suitability.

The research by JMRN as well pointed out that, the importance of brand name to women consumers in Japan is diminishing (JMRN, 2007, p. 7). The decrease in the importance of a brand name is a crucial pointer of the change from the consumption of fashions, cuteness, and brands as collective code to consumption founded on personal taste.

Fig. 1: Women and consumption in Japan

Consumer mindsets and Approach

The modern shift past social codes based on traditions is affecting the basis of individuality for both male and female consumers. Consumers’ brand preferences progressively line up with their longing for coherence and comparatively advanced intensities of personality (JMRN, 2007, p. 8). JMRN recognised five existing fundamental requirements and alarms articulated by the modern active Japanese women consumers as the following:

- Shift from me and to me foremost: During the period of individuality, Japanese women consumers are searching for distinctive fashions, cuteness, and brands despite the price.

- Mind, Body, and Soul: Japanese women consumers are seeking improved brand knowledge.

- Variety in Brand existence: Japanese women consumers simply admit and consider that cheap brands are capable of conveying value as regards quality and usefulness.

- What is in a Tag? : During the period of inexpensive manufacturing, legitimacy still controls every other aspect.

- Emerald Effect: Japanese women consumers prefer “green” luxury.

The research by JMRN revealed an increasing opposition amid Japanese women consumers to having identical fashion and brands with everybody else. This tendency was mainly obvious among Japanese female consumers of all ages, from the youthful parasite singles to elder wealthy women (SueLin, 2010, pp. 2810-2812). Some of the luxury brands that most Japanese women consumers prefer include the following.

- Gucci – Bottega Veneta -Hermes

- Tiffany – Bulgari – Coach

- Christian Dior – Car tier – Chanel

- Louis Vuitton

Forty-four percent of the women consumers in Japan prefer Louis Vuitton bag to other bags. The research by JMRN demonstrated that the degree of penetration is starting to stabilise in the modern Japanese fashions, cuteness, and brands market (Hata, 2003, pp. 4-7). In interviews, Japanese women across every age articulated the sense that an elevated penetration and profile of fashions, cuteness, and brands decreases their desirable value.

Further disparaging from the value of fashions, cuteness, and brands is the reality that several youthful women, comprising students from secondary schools, can now manage to pay for beautification packages (SueLin, 2010, pp. 2813-2815). Successful luxury brands are the ones that act in response to the preference of Japanese women consumers for distinctive products.

From the interviews, it was recognised that the Bottega Veneta, a brand from Italy, is achieving brand drive amongst Japanese women consumers because of its quality and distinctiveness. Despite the fact that just 5 per cent of interviewees asserted having a luxury brand from Bottega Veneta, 20 per cent pointed out that it is a successful brand at present. Chanel, Car tier, Christian Dior, and Coach embrace a comparable status.

On the other hand, brands like Gucci, Hermes, Tiffany, and Bulgari that have both high extents of brand responsiveness and market access are dropping off their impetus as Japanese women consumers progressively declare that these luxury brands do not merit their pricy costs (JMRN, 2007, pp. 9-11).

Variety

Japanese women consumers simply understand and deem that inexpensive fashions, cuteness, and brands could as well be of high quality and usefulness.

During the 1980s, the purchase of fashions, cuteness, and brands was anchored in their status and attractiveness. From the interview, 20 per cent of the Japanese women consumers had the same opinion that purchasing luxury brands expresses achievement and social grade. As the Japanese women consumers attain higher state of self-assurance, numerous do not consider the requirement to attest themselves through the purchase of a luxury brand.

Importantly, the marketers of fashion, cuteness, and brands are facing more difficulties with time in drawing and upholding devoted consumers, particularly as they become aged (JMRN, 2007, pp. 12-13). According to research, as the Japanese women consumers age, it turns out to be very hard for them to declare that fashion, cuteness, and brands offer them confidence.

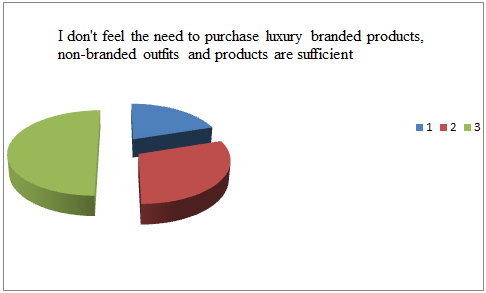

Simultaneously, the earlier negative feelings of Japanese women consumers as concerns buying of brands at reduced prices are varying (Silverstein, & Fiske, 2003, pp. 32-35). At present, it is generally satisfactory to acquire cheap brands from discount shops. Half of the respondents did not consider the requirement to possess luxury brands any longer since they consider non-branded outfit and other products as satisfactory.

At around the age of 40 years, Japanese women consumers confirmed to be strongly attracted to non-branded fashion, cuteness, and brands as compared to women around the age of 20 years. This aspect implies that Japanese women consumers in later life might unsurprisingly prioritise the needs of their families (husband and children) than need for self-spending, or merely have more attention in usefulness of brands.

With an amalgamation of enhanced self-assurance, changing life phase priorities along with an adjusted description of worth, Japanese women consumers are gradually combining high and low standards of living, a tendency as well witnessed across international markets (JMRN, 2007, pp. 14-16). A number of consumers decisively reduce in one section to indulge in a different one.

Fig. 2: Sufficiency of non-branded products

Discussion

Democratisation of fashion, cuteness, and brands coupled with the frequency and convenience of luxury brands is as apparent amid Japanese women consumers as it is worldwide.

In Japan, market tendencies solicit the continuation of counter-inclinations, as revealed in consumer swings from fashions, cuteness, and brands that are excessively readily accessible. Contemporary luxury brands reflect influential yearnings for superiority, distinctiveness, and personal identities amid Japanese women consumers. Therefore, top brands are presenting limited and unique versions; nevertheless, Japanese women consumers are searching for profound associations with quality than merely purchasing of brands.

Research by JMRN established that a great number of aged women in Japan purchase non-branded products while most of the youthful women go for branded products. Generally, currently Japanese women consumers actually take pleasure in the knowledge of a fashion, cuteness, and brand, as compared to just purchasing the product itself. In the last decade, reactions of the marketers of fashion, cuteness, and brands to the needs of Japanese women consumers for entire brand knowledge have increased.

Going past the anticipated advanced ranks of consumer service, thriving fashions, cuteness, and brands now recommend enriching all features of the life of consumers coupled with full brand knowledge for body, mind, and soul. While Japanese women consumers crave for brand contacts past the retail setting, fashions, cuteness, and brands are no more merely selling to consumers, but are offering services to be examined for a particular extent of quality.

Conclusion

Fashion, cuteness, and brands that wish to be successful will be required to acclimatise and reflect on ever-varying consumer desires coupled with their mindsets and attitudes compelled by constantly varying social demographics.

Category income will constantly be held up by prosperous Japanese women as well as by the parasite singles. Nevertheless, fashion, cuteness, and brands that maintain their pulsate on the advancing tendencies might discover that fresh sectors can be cultivated past consumers that lie in the luxury supporter group in addition to the ones whose attention may be deteriorating.

While yearning for distinctive and quality products by Japanese women consumers rises, the significance that rests on brand name is declining and thereby offering opportunities for fresh entries (for instance from France) both at the luxury class and to safe fashion selections at cheaper prices (SueLin, 2010, pp. 2816-2821). The same methodology used in this paper can be employed in studying the association involving women and consumption in the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

References

Chadha, R., & Husband, P. (2006). The Cult of Luxury Brands: Inside Asia’s Love Affair with Luxury. London, UK: Nicholas Brealey International.

Eastman, J., & Iyer, R. (2012). The Relationship between Cognitive Age and Status Consumption: An Exploratory Look. Marketing Management Journal, 22(1), 80-96.

Hata, K. (2003). Louis Vuitton Japan: The Building of Luxury. Tokyo: Nikkei, Inc.

Japan Market Resource Network. (2007). Consumer Survey: Attitudes toward Luxury Brands. Japan: Japan Market Resource Network.

Nia, A., & Zaichkowsky, J. (2000). Do counterfeits devalue the ownership of luxury brands? Emeral Journal, 9(7), 485-497.

Silverstein, M., & Fiske, N. (2003). Trends, Brands, And Practices – The Boston Consulting Group’s 2004 Research Update to Trading Up: The New American Luxury. New York, NY: Penguin Group.

SueLin, C. (2010). Understanding Consumer Purchase Behaviour in the Japanese Personal Grooming Sector. Journal of Yasar University, 5(17), 2810-2821.

Tian, K., Bearden, W., & Hunter, G. (2001). Consumers’ need for uniqueness: scale development and validation. Journal of Consumer Research, 28(1), 50-66.