Introduction

Fake news is a form of propaganda that arises from inaccurate or deceitful reporting. According to Oliver and Wood (2014), fake news can be traced back to the 1835 Great Moon Hoax when a prank went viral in the U.S. and Europe following a publication in newspapers, including The Sun, describing the discovery of life on the moon. Later, the world learned that the news entailed half-truths. This hoax evidences the historical existence of misinformation in media platforms, although it is only in recent times that any propaganda has been termed as fake news. The 2016 U.S. elections introduced the debate on fake news in the public domain.

During this time, news such as the move by the Pope to endorse the candidature of President Trump spread across social media platforms, despite the lack of reliable evidence. Calls from different bodies, including the American Library Association, have been made emphasizing the need for shunning fake news across different social media platforms and websites (Spratt & Agosto 2017). The goal is to enhance the dissemination of meaningful, truthful, and unswerving information.

The above highlights have a bearing concerning the focus of the current topic because they underline the need for worldwide media firms to police and/or evaluate contents published in the current era marked by difficulties in differentiating fake and truthful news in social media and websites. Fake news entails a global phenomenon, which is shaping the conduct of 21st-century adolescents. Consequently, the literature review presented in this study suggests that young people aged 11 to 18 years in the UK’s secondary schools lack the necessary skills to identify fake news or information from websites and social media platforms. This study seeks to set a foundation for future explanatory research based on the study topic.

Literature Review

Major Issues and Debates Concerning Fake News

In the digital century, middle-school-going children can fluently engage in verbal and non-verbal communication via digital platforms such as social media and websites. Amid the earlier mentioned historical dating of fake news to the 1835 prank, the phenomenon has escalated following the emergence of new media tools, including social media and other online platforms such as websites. Although some media segments commonly regarded some forms of news as fake, there lacked a scholarly agreement on what amounts to fake news (Waldrop 2017).

However, attempts have been made to define it. Rather than defining it, Waldrop (2017) identifies propaganda as occurring on a large scale, whereby face value jokes, the manipulation of real facts, providing intentionally deceptive information, and giving stories reflecting contentious truth are common types of fake news. Based on the writer’s judgment, the above description may be misinterpreted because it does not reflect on what fake news entails.

As a result, Spratt and Agosto’s (2017) definition is treated as convincing because it not only captures the components of fake news but also indicates its level of infiltration into the field of journalism. According to the authors, fake news is entirely crafted and maneuvered to take the form of a persuasive reporting that seeks to capture the interest of the targeted audience (Spratt & Agosto 2017).

Considering the above different manifestations of fake news, Waldrop (2017) regards critical literacy as essential in helping children to establish a foundation for identifying and screening fake news. Consequently, 11 to 18-year-olds interacting through social media platforms should possess critical literacy skills necessary for their effective navigation through the digital age (Spratt & Agosto 2017). However, considering the focus of the current paper, a question arises on whether the UK’s secondary school children aged 11 to 18 years have the skills to identify fake news or information from websites or other social media platforms. A response to this scholarly question warrants consideration of the extent of the problem among the 11-18-year-olds based in the UK.

Key Theoretical and Conceptual Considerations

Different scholars propose various theories and concepts for teaching digital literacy. The models seek to ensure that young people develop the capability to recognize fake news featured on Internet-based social media platforms. According to Floyd and Morrison (2014), it is crucial to acknowledge the social-cultural concept that children learn social media from the society where older folks such as parents and friends introduce young people to the Internet.

The theory of constructionism, which was engineered by Seymour Papert, reveals that knowledge is constructed in various ways, including the use of Internet-enabled devices such as laptops and phones (Kazakoff 2014). In my opinion, although this theory appreciates that children can gain cognitive expertise from using the Internet, it fails to acknowledge the fact that their (children) social skills and the need to remain in touch with their peers may tempt them to spread or imitate propaganda.

In the global domain, Cranwell et al. (2016) estimate that 80% of young people aged between 10 and 15 years can access the Internet in the UK using phones or other gadgets. This high preference continues in an era when curriculums in many nations have failed to incorporate lessons on key social aspects and issues encountered in children’s online life (Wilkinson & Penney 2014). For instance, Makhdoom and Awan (2014) reveal how the English curriculum does not address mechanisms for analyzing online content in the quest to identify fake news.

A survey conducted in the UK revealed that almost 60% percent of children between 8 and 11 years and approximately 70 percent of those between 12 and 15 years claimed to visit news online applications and sites in 2016 (Lelkes 2016). According to the report, 20% of these young people believe that contents available on such platforms are factual and perfect (Lelkes 2016). Arguably, this figure of 20% presents a significant proportion of young people who lack the expertise to recognize not only the existence of fake news in social media platforms and websites but also those who are clueless about the ill motivation leading to posting fake news.

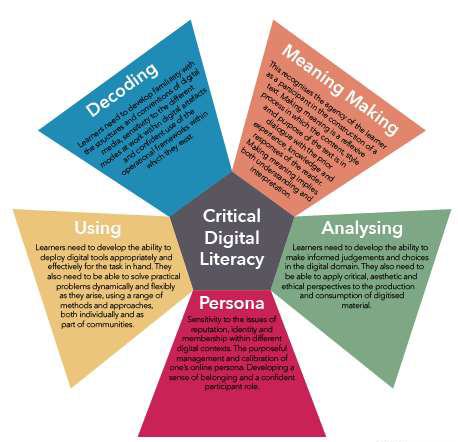

Firkins (2015) emphasizes the Four Resource model, which is a process-oriented digital literacy framework. It opposes the conventional syllabus-centered approach to inculcating digital literacy skills among school-going young people. Indeed, Firkins (2015) supports this conceptual framework by noting that it can provide a reliable mechanism for enhancing the integration of digital literacy across the UK’s curriculum. The Four Resource model has four main pillars.

The first one focuses on breaking the textual code. This step leads to the second pillar of meaning development. The two pillars result in the third step of ensuring that learners progress to become text users. The last pillar ensures the development of text analyst learners. Based on my judgment, this conceptual framework fails to establish details of specific competencies. This gap may have informed the argument by Firkins (2015) that teachers should interpret and manage the development of appropriate competencies depending on how digital information ecosystems evolve.

Figure 1 shows the Four Resource Model framework for inculcating digital literacy. From the diagram, the model has an additional fifth pillar, namely, the persona. Hinrichsen and Coombs (2013) added it arguing that more conceptual digital literacy indicates a prospect for an equivalent transformation from skill-based subjects to the notion of well-founded training. Nevertheless, I believe that the existence of digital literacy conceptual and theoretical frameworks does not imply that instructors in the UK teach 11 to 18-year-old young people about the skills necessary to identify fake news. The above claim is founded on the awareness of the high percentage of young people who are increasingly spending most of their time accessing news online without questioning the reliability and accuracy of news as Cranwell et al. (2016) reveal.

Do the UK’s Secondary 11-18-Year-Olds have the Skills Necessary to Identify Fake News?

Spratt and Agosto (2017) support the line of argument that 11-18-year-olds lack the appropriate expertise to discern fake news. According to the authors, children’s minimal skills in identifying fake news subject them to the risk of incarceration, especially when such misinformation spreads to the respective government authorities. The action taken follows the impact that such fake news from children may have on various areas, including politics.

For example, concerning the Brexit referendum votes in the UK, researchers concluded that fake news had little implication on the results (Allcott & Gentzkow 2017). In my opinion, this research is unreliable because it ignores details such as the age or level of education of individuals who provided data to enable such a conclusion. In other words, it is crucial to point out that such a conclusion was made regardless of whether those who upheld such an opinion were children or not.

In case the UK experiences economic disadvantages in the future, its inability to identify fake news in social media, the source, and the necessary measures to address the situation will be a regrettable problem. Consequently, it is important for the UK to ensure that young people aged 11 to 18 years develop skills for discerning fake news at an early age. For instance, the UK’s curriculum may incorporate lessons for teaching appropriate behaviors for children, especially when they are analyzing and synthesizing information encountered in digital media platforms.

However, although much of the literature on young people’s inability to identify fake news is based on large-scale U.S. studies, Picton and Teravainen (2017, p. 8) point out, “a survey of 1,503 UK teachers, which found that 35% reported pupils citing clearly fake news or false information online as facts within their work”. This finding suggests the degree of students’ lack of expertise concerning verifiable information to support their points of arguments or counterarguments. In fact, the inability to identify fake news but include them in their work as evidence suggests their apparent lack of critical skills necessary to verify false information on social media platforms.

Although Pangrazio (2016) questions the line of argument that children lack the requisite skills to detect fake news, a close examination of the authors’ conclusion may be narrowed down as supporting Picton and Teravainen’s (2017) school of thought. Pangrazio (2016) only brings the aspect of the pedagogy of critical digital literacy whereby the question its level of incorporation into the country’s school curriculum. They reveal how teachers take noble roles to ensure that young people develop the necessary critical analysis skills by way of questioning any information they encounter on social media platforms and websites.

Probing is necessary to help young people to determine the reliability of information presented to them. Based on the writer’s opinion, Pangrazio’s (2016) line of thought is practical because digital literacy and the critical analysis of digital information can be integrated into the UK’s curriculum in primary and secondary education levels. This strategy can allow young people to acquire skills from the subject congruently with other class-acquired knowledge repositories. In this sense, digital literacy entails a mechanism of building talent appropriate for discerning fake and truthful news rather than the introduction of a completely new subject in the UK’S primary and secondary schools.

In my opinion, the blame concerning 11-18-year-olds’ lack of expertise in discerning fake news in the UK should not be solely directed to them. It is equally imperative to question whether teachers in the UK understand the need for equipping learners with such skills. Firkins (2015) borrows this line of argument by questioning the level of the inadequacy of the skills among the UK teachers.

Based on the opinion given by Pangrazio (2016), even though the term digital literacy can be found in almost all policy documents in the UK’s education sector, teachers have insufficient understanding of the concept. This observation substantiates the writer’s concern regarding how such information-deficient teachers in the UK can teach digital literacy effectively in schools to the extent that 11-18-year-olds can identify fake news in social media platforms and websites.

No studies in the current literature have examined whether teachers and government authorities are aware of the need to incorporate subjects that can equip 11-18-year-olds with the necessary expertise to distinguish reliable news from counterfeit information. In my judgment, teachers are responsible for propagating these skills. Indeed, there is a central and common agreement among educational scholars that teachers are critical success factors in boosting critical literacy skills.

For example, borrowing from the views presented by Anwaruddin (2016), the UK’s learners need to have teachers who are confident and assertive about critical skills. The House of Lords Communications Committee held a similar position when it recommended the need for “schools to teach online responsibilities, social norms, and risks as part of mandatory Ofsted-inspected Personal, Social, Health and Economic (PSHE) education” (Picton & Teravainen 2017, p. 9). The commission went on to recommend the need for training teachers and ensuring they are resourceful in teaching digital literacy skills across the UK’s curriculum.

The literature examined in this paper has enhanced my knowledge concerning the topic under investigation. For instance, considering that social media and websites permit users to be newsmakers, it becomes difficult to differentiate between the original and verifiable piece of news. I have realized that millennials focus on how to spread the news by sharing social media information with friends, as opposed to criticizing the authenticity of the news shared (Pangrazio 2016).

However, even where some young news consumers may doubt the reliability and accuracy of news on social media and websites as Martin (2018) suggests, the literature has helped me to realize that people, including the 11-18-year-old population segment, still share an otherwise piece of fake news by treating it as a joke. This step creates a situation whereby the person consuming news on social media after being recommended to visit a particular link by a friend may fail to interrogate the age or experience of the source, in this case, an 11-18-year-old child. He or she may strongly believe in the friend recommending the link. Therefore, the whole debate shifts from the ability to detect fake news to trusting that a friend cannot share inaccurate news.

Consequently, I am now aware that unless teachers and even government agencies instill the expertise to discern fake news among children in the UK, the spread of propaganda by 11-18-year-olds in this country remains a nightmare.

In the UK, the newspaper sector experienced the worst performance since the global recession of 2007 and 2008. According to Williamson (2016), the daily circulation of newspapers fell by about 7 percent. This reduction may have significantly affected news consumption not only by 11 to 18-year-olds but also by the general population. A decrement in newspaper circulation in an increasing population implies that a growing population segment seeks alternative sources of news.

Recently, the globe has witnessed a massive penetration of smartphones and other mobile devices that enable users to easily access the Internet (Waldrop 2017). Hence, websites and social media platforms remain one of the easiest ways of accessing news, especially among the 11 to 18-year-old population segment in the UK. However, the literature has clarified to me that this segment may not only lack the ability to detect fake news but also consume information differently compared to past generations. Waldrop (2017) supports this assertion by observing that instead of just consuming news, the current generation becomes an important element of the process of the news flow chain.

Conclusion

Based on the literature review findings, pre-teen and teens in the UK spend much of their free time interacting through social media and other Internet-based sites. Others share the information they encounter in various social media platforms. The content therein can be spread to millions of other pre-teen and teens in a matter of minutes, thanks to the power of social media. However, they are largely clueless or unaware of the need to evaluate the accuracy or the trustworthiness of the information they come across or spread to their friends. This situation poses an enormous threat, especially among young people who cannot evaluate and differentiate counterfeit information from reliable news.

As discussed in the literature review, while some limited scholars argue that social media experts and professionals should now recognize that people doubt information carried by media platforms, another stream contends that people across all demographics do not interrogate the validity of the news they encounter in the social media and the Internet. In the UK, it is difficult to find a large-scale survey on whether 11-18-year-olds have requisite digital literacy skills to help them in identifying fake news.

Nonetheless, the literature review responds to the proposed research question by revealing that indeed a high number of this population segment lacks the requisite expertise to recognize fake news or information on websites and social media platforms. While the UK government features digital literacy through the education sector as an important critical thinking skill in its policy papers, the literature review suggests that teachers have not mastered the concept and hence the reason why 11-18-year-olds continue to spread fake news because of the lack of understanding of what it entails.

Reference List

Allcott, H & Gentzkow, M 2017, ‘Social media and fake news in the 2016 election’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 31, no.2, pp 211-236.

Anwaruddin, S 2016, ‘Why critical literacy should turn to ‘the affective turn’: making a case for critical affective literacy’, Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 381-396.

Cranwell, J, Whittamore, K, Britton, J & Leonardi-Bee, J 2016, ‘Alcohol and tobacco content in UK video games and their association with alcohol and tobacco use among young people’, CyberPsychology, Behaviour & Social Networking, vol. 19, no. 7, pp. 426-434.

Firkins, A 2015, ‘The four resources model: a useful framework for second language teaching in a military context’, Technical Studies Institute Journal. Web.

Floyd, A & Morrison, M 2014, ‘Exploring identities and cultures in inter-professional education and collaborative professional practice’, Studies in Continuing Education, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 38-53.

Hinrichsen, J & Coombs, A 2013, ‘The five resources of critical digital literacy: a framework for curriculum integration’, Research in Learning Technology, vol. 21 no.1, pp. 1-16.

Kazakoff, E 2014, ‘Toward a theory-predicated definition of digital literacy for early childhood’, Journal of Youth Development, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1-18.

Lelkes, Y 2016, ‘Mass polarisation’, Manifestations and Measurements Quarterly, vol. 80, no. 1, pp. 392–410.

Makhdoom, M & Awan, S 2014, ‘Education and neo-colonisation: a critique of English literature curriculum in Pakistan’, South Asian Studies, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 411-421.

Martin, E 2018, ‘The state of social media’, EContent, vol. 41, no.1, pp. 22-24.

Oliver, E & Wood, W 2014, ‘Conspiracy theories and the paranoid style(s) of mass opinion’, American Journal of Political Science, vol. 58, no. 4, pp. 952–966.

Pangrazio, L 2016, ‘Reconceptualising critical digital literacy’, Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 163-174.

Picton, I & Teravainen, A 2017, Fake news and critical literacy: an evidence review, The National Literacy Trust, London.

Spratt, H & Agosto, D 2017, ‘Fighting fake news: because we all deserve the truth: programming ideas for teaching teens media literacy’, Young Adult Library Services, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 17-21.

Waldrop, M 2017, ‘The genuine problem of fake news: intentionally deceptive news has co-opted social media to go viral and influence millions. Science and technology can suggest why and how. But can they offer solutions?’ Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 114, no. 48, pp. 12631-12634.

Wilkinson, S & Penney, D 2014, ‘The effects of setting on classroom teaching and student learning in mainstream mathematics, English and science lessons: a critical review of the literature in England’, Educational Review, vol. 66, no. 4, pp. 411-427.

Williamson, P 2016, ‘Take the time and effort to correct misinformation’, Nature, vol. 540, no.7632, pp. 171-172.