Introduction

Background of the Study

Brand image is considered one of the most important aspects of present day marketing strategies, especially where the fashion industry is concerned. Based on the analysis of Ross & Harradine (2010), the present day fashion industry is a multi-billion market with roughly $500 billion in annual sales which encompasses a multitude of brands and product types (Rajagopal 2011) Through the use of their respective brand images, companies create a means of distinction from their other competitors.

This method of distinction can manifest in a myriad of possible variants of present day fashion such as items that are considered chic, hip, counter culture or luxury oriented. The end result is that there are multiple companies that field a wide variety of fashion styles that are all attempting to penetrate the same consumer market, albeit at different levels (i.e. high class, mid class, average, etc.) (Stephen & Galak 2012).

It is within this context that this paper will examine the effect of brand image on consumer purchasing behaviour with the UK. This type of examination will encompass the strength of brand images and celebrity endorsed products and will examine the capacity of brand image to influence consumers with or without celebrity assistance (Shute 2004; Roehm, Pullins & Roehm Jr. 2002). It is anticipated that this paper will yield a considerable amount of data that will contribute towards a better understanding on the impact of brand image on consumer purchasing decisions. It is the assumption of this study that brand images can stand alone without celebrity assistance but are inherently limited by price, budget constraints, preferences and the rational behaviour of consumers.

Significance of the Study

The significance of this study is in its potential contribution to help clothing companies within the UK make better marketing decisions when it comes to utilizing endorsement deals with celebrities or focusing on the implementation of traditional advertising campaigns in their marketing efforts. While it may be true that in previous decades celebrity endorsements have helped the brand efforts of numerous companies, the fact remains that the concept of “brand image” being associated with celebrities has become increasingly questionable given the oversaturation in the UK clothing market.

An examination must be conducted regarding present day perspective of consumers regarding the impact of brand image and whether celebrities continue to be a relevant means of making a company’s brand image better. Through this study, a better understanding of consumer purchasing behaviour within the UK clothing industry will be established which will go a long way towards improving present day brand development strategies within this particular industry.

Aims/ Objectives of the Project

- The main objective of the research shall be to determine the current impact of brand image on consumer purchasing behaviour in the UK clothing industry.

- The other objective of this research is to determine whether celebrity endorsements continue to be an effective means by which companies improve their brand image and penetrate their desired target markets.

- The research paper shall also utilise various theories on consumer behaviour in order to properly interpret the data that was received.

Research Questions

The proposed research shall seek to address the following questions:

- What is the impact of brand image on consumer purchasing behaviour within the UK clothing industry?

- Do celebrity endorsements continue to be relevant when it comes to the development of a company’s brand image?

Scope of the Study

The independent variable in this study consists of the academic literature that will be gathered by the researcher for the literature review while the dependent variable will consist of the responses gained from various consumers within the UK that will be recruited. It is anticipated that through a correlation between the literature examined on consumer behaviour and the responses of UK based consumers, the researcher will in effect be able to make a logical connection regarding the current effectiveness of brand image on influencing consumer purchasing behaviour.

It is anticipated by the researcher that the data collection process is expected to be pretty straightforward (i.e. researching online and collecting data from participants); however, some challenges may be present in collecting data involving consumer purchasing behaviour that is to be utilised in this study. Such issues though can be resolved through access to online academic resources such as EBSCO and Jstore as well as popular magazines (ex: Time) and other sources of potentially relevant information.

Furthermore, online websites would have several online articles which contain enough information that should be able to help steer the study towards the proper direction. Do note though that these websites will merely act as a guide and will not be utilised primary or even secondary sources of information. It must be noted that the time constraint for this particular study only allowed a limited number of individuals and also a limited amount of flexibility when collecting the research data.

Limitations

The main limitation of this study is in its reliance on survey results as the primary source of data in order to determine the effect of brand image on consumer purchasing behaviour in the UK clothing industry. There is always the possibility that the responses could be false or that the consumers in question are answering randomly without actually trying to understand the data that is being presented. While this can be resolved by backing up the data with relevant literature, it still presents itself as a problem that cannot be easily remedied.

Literature Review

Introduction to Literature

Through this section, readers will be able to better understand the various factors that influence consumers to choose particular brands and what theoretical concepts can be utilised in order to properly understand their purchasing behaviour when subject to outside influences. The literature in this review is drawn from the following EBSCO databases: Academic Search Premier, MasterFILE Premier; as well as Jstore and various internet sources when applicable. Keywords used either individually or in conjunction include: celebrity, brand image, consumer, purchasing decision, perception, price, and rationality.

Analysing the Importance of Brand Image on Purchasing Decisions

Going over the various luxury clothing brands that are currently in business within the UK, it can be seen that when they are broken down into their basic components, these items, whether they consist of shirts, bags, jeans, etc. are comprised of the same materials that can be found in other clothing brands, however, they are sold at a quarter of the price. De Barnier, Falcy & Valette-Florence (2012) explain that through the efforts of various marketing departments, various customers have developed the notion that particular types of fashionable items that have a certain brand name plastered on them have a far higher quality as compared to similar items from lower priced retailers.

Clothing companies would of course defend the veracity of such claims, however, the fact remains that through the investigation of Patton (2006), it was shown that suppliers for high end clothing brands were also the same suppliers for smaller and far less well known clothing manufacturers as well. Further analysis by Sonnier & Ainslie (2011) also showed that the overall quality of component items that were used in the production process were similar in style, design and the materials that were being used.

From this perspective, it must be questioned as to why consumers continue to purchase particular brand items for an exorbitant amount when similar and far cheaper alternatives are present (Xueming, Wiles & Raithel 2013). It is true that the designs utilised by certain brands do exceed those of other companies in the clothing industry, however, if the type of material used is the same and the only difference is the design then if the design could be replicated and the same materials used then would not that mean that the same type of product could also be produced as well? Pina, Iversen & Martinez (2010) say that this is not necessarily true from the perspective of consumers and points towards an experiment that was conducted involving consumers and their perspective regarding luxury products and their ordinary counterparts (Pina et al. 2010; Kim & Yoon 2013).

In this analysis, consumers were presented with two wallets that, for all intents and purposes, were similar in every way possible, yet one had a popular brand name plastered on it while the other had the name of a relatively unknown company. When asked to evaluate the difference in quality, design, and the aesthetic appeal, a vast majority of the participants agreed that the wallet with the luxury brand was far better despite the fact that the materials, design, and the overall quality of production were the same (Woo Jin & Winterich 2013).

The only difference between the two was that one had a well known designer label while the other did not. This apparent bias despite two products being exactly the same was analysed by Magnoni & Roux (2012) with the conclusion being that consumers had a preconceived notion of “superiority” regarding products that were attached to a particular brand image. It is this preconceived notion of superiority that influences consumers to buy products that have a markup well beyond 500% of the original production cost.

To better understand why consumers are apparently “blinded” by brands which results in an illogical purchasing decision (i.e. paying far more for a product than they should), it is necessary to examine the work of Kort, Caulkins, Hartl & Feichtinger (2006) which delved into the social connections between brand image and present day consumers. Kort, Caulkins, Hartl & Feichtinger state that the apparently illogical behaviour of consumers when it comes to popular brands actually boils down to the method in which these brands associate themselves with particular trends, celebrities, etc. in order to justify their high costs (Ferraro, Kirmani & Matherly 2013).

The brand image in this case creates what Bellezza & Keinan (2014) define as “an acknowledged societal connection” which can be construed as possession being correlated with belonging. Jung, Lee, Kim & Yang (2014) go a bit further into this topic by explaining that ownership of an article of clothing with a particular brand is connoted as being a form of “identification” within present day society wherein people buy a piece of expensive branded clothing not because they actually need it (there are cheaper alternatives), rather, they buy it because they want to feel that they belong to a particular group of people.

This method of “identification” is not necessarily a result of popular culture (however it does have strong connections to it as seen in the forms of idolism and emulation that people have towards celebrities), rather, this behaviour can be considered as a manifestation of the sense of community that is inherent in all humans (Spiggle, Nguyen & Caravella 2012).

Various studies have shown that man (i.e. humanity) is a social creature and actually craves societal contact and desires to be identified with a particular type of group. It is based on this that the concept of identification through branded fashion is a way in which man has created a means by which he is able to identify himself with a particular social group and once this particular sense of identification is achieved, they derive from such an act a sense of fulfillment and happiness since they feel that they belong (Turner 2005; Sichtmann & Diamantopoulos 2013). If you think about it from this particular perspective this helps to explain why people go out of their way to pursue the latest fashions, conform to the latest trends, or buy ridiculously overpriced items that they can get for a fraction of the cost elsewhere, they are simply doing so in order to conform to their desire to feel that they belong to a greater whole (Vernuccio 2014).

Brand Image and Celebrity Endorsements

It is within this saturated market that in order to gain a competitive advantage various clothing brands attempt to leverage their brand image through the use of celebrity endorsements in order to create a positive association. Known as “growth through association”, fashion brands attempt to capitalise on the popularity of celebrities resulting in a psychological correlation between that celebrity and the brand that they are endorsing (Luo, Raithel & Wiles 2013). This process, which is defined as “the dynamics of public interest”, occurs when members of the general public (that are fans of popular culture icons) become fascinated with various celebrities to such an extent that they attempt to emulate them.

The manifestation of such a behaviour takes the form of “celebrity emulation” wherein they end up buying coats, t-shirts, shoes and other types of fashionable items that are in the same style as those worn by their favourite celebrity (or pop culture icon). Companies exploit this type of behaviour by utilizing celebrity endorsement deals in the form of corporate sponsorship agreements by having certain celebrities present their brand.

Examples of this in the UK clothing industry can be seen in the case of Burberry wherein they hired Emma Watson to represent their brand in 2012 (Satomura, Wedel & Pieters 2014; Sood & Keller 2012). Other examples can be seen in sponsorships associated with Daniel Craig (Tom Ford Suits), Keira Knightly (Chanel) and many other examples that are too numerous to mention. Suffice it to say, the association of brand image with celebrities is strategy that has been highly utilised in order to increase the level of consumer patronage of a company’s brand (Satomura et al. 2014).

As explained by Marwick (2010), brand image as it manifests in the present day ubiquitous nature of pop culture fandom has resulted in brands being associated more with who represents them rather than the brand itself (Swoboda, Pennemann & Taube 2012). What must be understood is that current trends in the clothing industry all have a habit of appearing one day and disappearing the next day (Gwinner & Eaton 1999).

In fact, with a few notable exceptions, brands that were popular two to three decades ago are no longer around or their fan base has significantly decreased as compared to when they were at the height of their popularity. Rae (1997) delves more into this by explaining that the popularity of brands is normally associated with their period of entry into the fashion world and the means that they penetrate into a particular consumer segment. Individuals such as Coco Chanel popularised “daring” luxury fashion items for women and the end result was a surge in popularity for the brand Ms. Chanel established during the 1920s till the 1950s. However, as noted by Linyun, Cutright, Chartrand & Fitzsimons (2014), the popularity of the Chanel brand has been in decline as of late as its consumers that were around during the height of its popularity have died off with present day consumers associating the brand as being far too “aged” when compared to present day fashion brands that appeal to the “young masses”.

This particular situation is not unique to the Chanel brand image, rather, it encompasses brands such Christian Dior, Louis Vuitton, etc. which have all experienced contractions in their relative popularity when compared to new brands that have developed within the past 10 years (Folse, Burton & Netemeyer 2013). From this example, it can be seen that brand image can have an impact on consumer purchasing behaviour wherein consumer perspectives regarding the association of a brand with the type of aesthetic appeal desired by present day buyers (i.e. to be chic, hip or have a distinctly counter culture design) can impact the rate of sale (Magnusson, Krishnan, Westjohn & Zdravkovic 2014).

Do note that another aspect that can be taken from this example is that brand image can be developed outside of celebrity endorsements. For instance, brands such as Levi’s Strauss and Co., Gap, Banana Republic and numerous other clothing brands have been successful in their respective markets despite having relatively little exposure to the utilisation of celebrity of endorsement deals (Simões & Agante 2014; Dolnicar & Grün 2014). As such, it can be seen that brand image and effect on consumer purchasing behaviour can exist outside of the spectrum of being correlated with celebrities in order to be popular.

Consumer Buying Behaviour in the UK Clothing Industry and the Various Factors that Influence it

In this section, what will be tackled are the factors that influence consumer buying behaviour in the UK clothing industry. It is anticipated that through the data that will be analysed, this will help to shed light on the consumer decision process and how brand image factors into it (Chunqing, Jing, Li & Songling 2014). First and foremost, it is important to note that various theories surrounding consumer decision making processes assume that consumers pass through distinct stages during the process of selecting a particular fashionable item to buy (Younghee, Won-Moo & Minsung 2012). Within the context of the consumer buying experience, what must be understood is that a consumer of dresses, pants, and other types of fashion is influenced by a myriad of different factors that affect the way in which they choose to patronise a particular brand.

This can range from various psychological reactions such as the way in which they think and feel about different products (i.e. brand perception) to the way in which the market environment they are currently present in affects the way in which they perceive a particular product or service (i.e. local culture, their family, local media influences etc.) (Andzulis, Panagopoulos & Rapp 2012). One example of a psychological reaction within the UK was a shift in professional women’s attire during the late 1990s from traditional long hemmed skirts to pant suits.

Dall’Olmo, Hand & Guido (2014) explain that the growth of this particular style was heavily influenced by the growing societal perspective surrounding feminism and its expression through stylistic choices. It was due to this brand perception for various clothing companies within the UK changed from the “girly” towards the “empowering” (He & Lai 2014). This resulted in various women eschewing traditional female attire in favour of something that was more “manly” (Kort, Caulkins, Hartl & Feichtinger 2006). Oddly enough, this particular stylistic choice has begun to run its course with a new shift in place resulting in women now preferring skirts once again (Sela, Wheeler & Sarial-Abi 2012).

This is not the first time such a shift has occurred since during the 1930s with the development of the pant suit by Chanel, a resurgence in the popularity of “empowering” clothing came about, which subsequently changed by the 1960s (skirts became popular again) (Romaniuk, Bogomolova & Riley 2012; Aggarwal & McGill 2012). As it can be seen, consumer buying behaviour is heavily influenced by trends as they occur resulting in consumers purchasing brand name goods in order to “keep up with the trend” in fashion and societal thinking at the time.

One way to explain such behaviour can be seen in the work of Levy (2011) which explained that the psychological reaction consumers feel towards particular brands is a form of irrational exuberance which manifests as a direct result of their desire to showcase that they belong to particular societal groups. Irrational exuberance can be thought of as an individual basing their actions on the behaviour of other people without taking into consideration the full ramifications of their decision. For example, the sudden shift of women from traditional skirts to pant suits during the late 1990s did not take into consideration the high costs of having to replace their entire office wardrobe for what was essentially an overpriced suit for women.

Other similar examples of irrational exuberance for fashion during the 1990s was noted during the rather abrupt popularity of MC Hammer (a rap artist) and his trademark baggy pants that were several sizes too large (Fang, Jianyao, Mizerski & Huangting, 2012). Consumers actually went out and bought various iterations of the pants despite the fact that they looked absolutely ridiculous, at least by today’s standards.

The primary lesson that you can take away from this is that when it comes to conforming to fashion trends, there is a tendency among certain sections of the population to forego logic in favour of conforming to a trend (Freund & Jacobi 2013). This behaviour was noted in the first section of this literature review which explained how brand names tended to be used by people as a means of associating themselves with a particular class of individual (i.e. rich, well to do, fashionable, etc.) (Thompson, Rindfleisch & Arsel 2006; Lim & Weaver 2014). Thus, fashion trends and their subsequent popularity can be considered as a manifestation of the desire of people to feel that they “belong” to a certain group with brand images becoming the means by which people are classified under a particular group of people.

Another example to take into consideration is when the general environment influences consumer purchasing behaviour. One case in which this was seen was during the 2008 financial crisis and the subsequent financial recession in the UK which greatly affected the way in which consumers perceive brand name fashions (Bremner & Lakshman 2007). This was due to the fact that there was an “atmosphere” of apprehension at the time due to the adverse impact of the financial crisis which made purchasing high end branded goods less appealing. The basis behind this was related to the desire to survive financially rather than to feel that they belonged to a particular group (Cleeren, Van Heerde & Dekimpe 2013). From this perspective, it can be seen that irrational exuberance can often be overridden in cases where a person has limited financial means.

One way in which this becomes immediately obvious can be seen in the case of the working class within the UK and their limited financial means. While some members of this community desire to wear high-end branded goods, the fact remains that their financial situation would restrict their capacity to do so (Langlois & Downs 1979; Mehta 2012). As such, it can be stated that the capacity of a brand image to result in the sale of a product is limited by the income of the consumer. It is from this perspective that the next section will delve into the theory of consumer behaviour which takes into consideration price, demand and perceived value in order to understand the purchasing decisions behind particular fashion products. The next section will act as the basis behind the analysis portion of this study when it comes to determining how brand image impacts consumer purchasing behaviour.

Theory of Consumer Behaviour and the UK Clothing Industry

The theory of consumer behaviour that will be utilised in examining the UK clothing industry revolves around the concept of the perceived value or satisfaction that a consumer derives from the purchase of a particular fashion brand (Shih-Ching, Soesilo, Dan & Di Benedetto 2012). To understand the demand side of market consumption in the UK clothing industry, the theory of consumer behaviour uses two distinct methods of measurement, namely Total Utility (TU) and Marginal Utility (MU). Total utility is defined by various experts in the field of consumer behaviour as being the equivalent to the total level of satisfaction that a consumer can get from the purchase of clothes (Shih-Ching et al. 2012). Within the context of this examination, this comes in the form of the total amount of satisfaction that a consumer derives from purchasing a particular type of brand.

When it comes to analysing consumer behaviour, marginal utility can be described as an add-on, namely it is the additional form of satisfaction that a consumer can get from the purchase of an added portion of a particular good. In the case of certain fashion brands, the marginal utility derived is the exclusivity that is normally associated with certain clothing brands since only a certain number of people can afford clothes from companies such as Burberry, Channel, etc (ApeagyeI 2011). It must be noted though that while total utility increases with the overall level of quality seen in some clothes, at some point due to the continuous purchase of a particular fashion product, the overall yield will result in smaller and smaller levels of additional utility towards the consumption (Ivens & Valta 2012).

To better understand this point, one can imagine a woman buying a Chanel shirt from one of their exclusive stores in London (ApeagyeI 2011). While at the start of the purchasing experience the total utility and marginal utility are equal, however, if the woman were to go back and kept on buying the same type of product in order to be considered “cool and hip” the total utility would increase due to the consumption however the marginal utility would decrease over time as a result of the continuous consumption of the same product.

This can be interpreted as the woman only being able to wear one shirt at a time and the fact that she is buying the same type of shirt with the same label which results in a relative decrease in the variety of clothes she wears (i.e. she would get tired of wearing the same type of outfit again and again). This is based on the notion explained by Naylor, Lamberton & West (2012) that continuous consumption of the same type of product would eventually cause a person to get tired of consuming. As a result of such actions, the added value attributed to it continues to decrease over the course of consumption or in the case of this study the amount of purchases of branded goods made (Lovett, Peres & Shachar 2013).

It is based on this that when taking into consideration the purchasing decisions of consumers, continuous consumption of the same type of branded clothing would in effect decrease the marginal utility over time (Beneke, Blampied, Miszczak & Parker 2014; Guzmán & Paswan 2009). This is important to take note of since after a certain point that the decrease in marginal utility has been met; it is likely that consumers that purchase a particular clothing brand switch to another brand where they can derive more marginal utility.

Evidence of this was seen in a survey done by Ross & Harradine (2011) which examined the purchasing decisions of various consumers and noted that when it came to particular brands, consumers did not stick exclusively to a single brand when it came to the type of purchases made, rather, their individual wardrobes consisted of an assortment of different fashion brands (Hudders, Pandelaere & Vyncke 2013). When asked why they did not simply stick to a single brand, the consumers stated that they wanted a certain level of variety in the types of clothes they wore and did not want to stick to a single brand for their entire clothing needs. The next section will delve into the

The Four Fundamental Concepts of Consumer Choice and its Impact on Consumer Purchasing Behaviour in the UK Clothing Industry

In order to better understand consumer purchasing behaviour in the UK clothing industry, the four fundamental concepts of consumer choice will be taken into consideration. These concepts consist of the following: rational behaviour, preferences, budget constraints and prices.

Rational Behaviour

First and foremost, Mccracken (1989) explains that rational behaviour assumes that consumers are individuals who maximise their received income to achieve the best level of satisfaction from purchasing a particular type of product which in this case is a fashion brand. For instance, when it comes to shopping for clothes it is unlikely that a person would shop only for pants, no matter how much they like pants, since they also need shirts as well. They would this follow the process of rational behaviour and have a certain degree of variety in the type of clothes that they buy. However, it should be noted that this type of rational behaviour is based on the assumption that consumers will act in an economically competent manner. This takes the form of consumers not spending too much of their hard earned income on items they cannot use.

One example of irrational behaviour in this context would be if someone spent the entirety of their monthly income on clothes instead of food, electricity or rent (Ritch & Schröder 2012). It is based on this that the concept of rational behaviour assumes all consumers within the UK clothing market engage in rational buying behaviours which becomes the basis for any future analysis of consumer buying behaviour. Within the context of purchasing branded clothing, this means that consumers will have a “limit” to the amount that they can purchase on a monthly or annual basis (Syed Alwi & Kitchen 2014; Kum, Bergkvist, Lee & Leong 2012).

This is a particularly obvious in the UK clothing industry wherein despite the numerous styles, trends and fashions that are released per quarter, there is a limited amount of consumers that can actually purchase these goods at any given time (Hede & Watne 2013). The ideal situation for clothing companies would be if every time they released a new style all their former customers would go to their stores and purchase this product. However, this is unlikely to happen given the aforementioned limitations (Maehle & Supphellen 2011).

Preferences

It must also be noted that the concept of preferences is based on the fact that each individual consumer has their own personal preference towards a particular product that is in the market from which they are able to derive the greatest amount of total utility/ satisfaction. What this means is that despite a fashion brand placing their label on a particular type of sweater, if that customer prefers t-shirts over sweaters, no matter how appealing the brand is, that customer is unlikely to purchase that sweater (Herstein, Gilboa & Gamliel 2013). Taking this into consideration, it can be stated that the capacity of brand image to influence consumer choice is inherently limited to the type of product that consumers are oriented towards. In the case of fashion brands, this takes the form of the type of garment that a particular customer prefers (Anselmsson, Bondesson & Johansson 2014; Hankinson 2012).

While brand image can influence consumer choice under the same type of garment line, it has no effect if the consumer wants a completely different type of garment (Octagon and Premier Management Define Terms of Endorsement 2005). This example thus shows the effect that rational choice has on consumer purchasing behaviour in the UK clothing industry and how price and personal choice factor into the type of product that is bought.

Budget Constraints

When it comes to the different clothing brands currently within the UK, it is understood that under the concept of budget constraints each consumer has a fixed and finite income due to the limited amount of income each individual consumer is capable of achieving within a given month or year (Han, Nunes, & Drèze 2010). While under the auspices of the clothing industry it is assumed that there is unlimited demand for designer brand goods (which is true to a certain extent), however, this level of demand is offset by the limited income of each individual consumer (Fischer, Völckner & Sattler 2010). It is due to this that the clothing industry often has specific types of brands available that take into account varying income levels (Agnihotri, Kothandaraman, Kashyap & Singh 2012).

The reason behind this is quite simple, different clothing brands would attempt to appeal to different consumer groups. As such, it is not surprising that certain brands would appeal to the more affluent members of the population (ex: Chanel, Burberry) as compared to other brands that would focus on the Middle or Working class (ex: Gap, Levis, etc.).

Prices

In this last section involving the fundamental concepts of consumer choice, the primary assumption that is being analysed is that of consumers being part of the total demand within the UK clothing market (Zolkos 2012; Swoboda, Pennemann & Taube 2012). As such, due to the limited amount of income each consumer is capable of achieving they must choose to obtain the best combination of goods that maximises their total utility while at the same time remaining within a certain price range (Miller & Mills 2012).

Taking this into consideration, it can be stated that despite customers knowing the total utility they can get out of a particular clothing brand they buy, they are inherently limited by the price of the object in question (Balabanis & Diamantopoulos 2011; Lee, Lee & Wu 2011). While the concept of consumer preference plays an important role in the choice of what brand to buy, the fact remains that the remaining concepts of rational behaviour, budget constraint and price also play roles that can actually override the concept of preference.

While a consumer may prefer to buy a particular type of branded fashion item, barriers to this choice in the form of higher prices which directly conflicts with a consumer’s inherent budget constraints would thus change their pattern of behaviour to choose a more affordable solution in order to conform to what is rational (Kremer & Viot 2012). Within the context of the UK clothing industry, this takes the form of consumers purchasing a similar product under a more affordable brand as compared to purchasing the same product under a more expensive brand (Correia, Veríssimo & Cayolla 2013). It should be noted though that if a consumer is presented with two choices of the same product, namely one with a well known brand and the other being relatively unknown, and both have similar prices, it is likely that the consumer will choose the well known brand rather than the unknown one.

This decision is influenced by all concepts of consumer behaviour wherein preference and rational behaviour for well known brands that are supposedly of a better quality led the consumer to choosing the former rather than the latter. It must be noted that the theory of consumer behaviour is basically an examination of what influences a consumer’s choice in a particular product or service (Cassidy 2003). Should a consumer be presented with the same choice of two competing brands with both being within budget constraints and prices, the choice is usually left up to consumer preference (Bane, Dubin, Gage, Singh Gee, McIntyre & Murphy 2005; Batra, Ahuvia & Bagozzi 2012).

On the other hand, if a choice is beyond budget constraints, price level and is considered to be an irrational choice preference is no longer included into the decision making process (Erdogan & Drollinger 2008). Thus, in terms of understanding consumer purchasing behaviour, preference should not be considered the sole deciding factor in understanding consumer behaviour rather a combination of rational behaviour, preference, budget constraints and price must always be taken into consideration in order to understand how consumer behaviour towards a particular clothing brand (Erdogan & Drollinger 2008).

Theoretical Concepts

Vroom Expectancy Theory

On one end of the spectrum is Vroom’s expectancy theory which has the fundamental belief that people’s behaviour is shaped by a conscious choice (Lee, Chen & Guy 2014). In the case of celebrities being influencers of fashion trends, this comes in the form of an approach that states that consumers can be motivated to buy more and expensive products for the company is if there is a sufficient positive correlation between the effort they put into the purchase done and reward they are given (Navarro-Bailón 2012).

Maslow’s Theory of Needs

When it comes to consumer purchasing in the UK clothing industry, what must be understood is that based on Maslow’s theory of needs the motivation of consumers to buy certain products tends to change over time and, as a direct result, it would be necessary to for the company to change its method of marketing and sales along with these shifting needs (Lewis 2002). For example, Maslow states that once basic needs are met people tend to move onto satisfying other needs which are their motivating factors (Bellezza & Keinan 2014). In the case of sales in the UK clothing industry, this means that consumers move on from wanting look their favourite celebrity to actively taking the steps to look like them by buying the same fashions (Newman & Dhar 2014).

Methodology

Introduction to Methodology

This section aims to provide information on how the study will be conducted and the rationale behind employing the discussed methodologies and techniques towards augmenting the study’s validity. In addition to describing the research design, theoretical framework, and population and sample size that will be used in this study, the section will also elaborate on instrumentation and data collection techniques, validity and reliability, data analysis, and pertinent ethical issues that may emerge in the course of undertaking this study.

Role of the Researcher

The role of researcher in this particular study is that of a collector of data. This takes the form of the researcher being the primary point of contact when it comes to contacting via email, text or personal face to face communication to the necessary individuals in order to obtain the subject data need via a survey. During each individual survey distribution, the researcher will be the only point of contact with the research. This unfortunately brings up the issue of “interpretation bias” wherein what was stated by the consumer being surveyed is interpreted in such a way that it conforms to what the researcher is attempting to prove via the data collection process. In order to prevent accusations of unethical manipulation of data, the collection process will primarily be handled by surveymonkey.com (i.e. compilation) with the data only being corrected for grammatical consistency in order to be effectively understood. This ensures that the research data is consistent with proper academic ethics.

Research Design

This study utilises a quantitative research design to examine consumer data in order to determine the impact of brand image on consumer purchasing behaviour in the UK. This methodological approach will objectively answer the key research questions. For the purpose of data collection, the process that will be used is a survey based method of examination for the purpose of collecting participant data. This particular data collection technique technique is used when a researcher is principally interested in descriptive, explanatory or exploratory appraisal, and, as such, would be an ideal method for this study.

The justification for choosing an survey based approach for this particular study is grounded on the fact that it will utilise an online survey tool (surveymonkey.com) in order to collect and aggregate all the necessary data. Given the number of participants, their respective locations and the sheer amount of data that needs to be processed in order for the study to be completed, it was determined by the researcher that using an online survey maker and creating a link to a web page where they could input their information would be a far more efficient means of collecting data as compared to manual data entry via printed survey forms.

An analysis of related literature will be used to compare the study findings with other research on the impact of impact of celebrity endorsements in the development of the fashion industry. This particular method of analysis should help in connecting ideas and theories that have been established by past researchers. This would help to justify the various arguments that would be brought up by the researcher by having a sufficient academic foundation to base the arguments on.

Another factor that should be taken into consideration is the necessity to choose people who actually shop for branded clothing. This limits the potential number of individuals to people of sufficient income levels as well as removes those who do not shop for themselves (i.e. children and the disabled). Cluster sampling will be particularly helpful for the purpose of this study. This approach will enable the researcher to find the respondents in quick and easy fashion resulting in a far more efficient method of data collection.

Context

The data gathering procedure for the interview will be held over a 3 week period spanning various locations within the UK. The reason for such an approach is quite simple, location variety is essential in order to get a sufficiently varied collection of data from analysis. For each location, the researcher will spend approximately 3 to 4 days in order to gather the necessary research data.

The data collection process will be divided into two distinct aspects; the first will determine the overall impact of brand image on consumer purchasing behaviour while the second aspect will focus on celebrity endorsements of particular fashion brands and whether it can be considered an effective means of improving a company’s brand image. This takes the form of inquiries regarding whether people would actually purchase a type of dress, shirt, jacket, etc. once a celebrity endorses it, their likelihood of remembering a brand and connecting it to a celebrity as well as their capacity to have a favourite brand and connect it to their respective celebrity. This method of analysis will also attempt to examine income levels and its capacity to influence consumer purchasing behaviour outside of the brand image context that is being examined.

Research Subjects

The research subjects for this study on consumer purchasing behaviour in the UK will consist of individuals recruited from known associates of the researcher as well as complete strangers on the street. The primary criteria for participation in the study consist of the following:

- Must have knowledge on pop culture and must be knowledgeable about various clothing brands

- Must have knowledge regarding price, budgets and displays the capacity to understand rational shopping behaviour

- Should be urban resident due to the difficulty of gathering research subjects from rural areas

- Should fulfill either one of the following requirements: a college graduate, a current employee, an executive of a company, or an individual that handles the family budget

- The research subjects should also fall under the age demographic of 23 to 55 years of age to ensure that they have sufficient awareness regarding present day fashion brands

- Lastly, the research subjects that are included in this examination should only be local residents within the U.K. and should not merely be “visiting”. The reason for this is quite simple; since the study is examining consumer purchasing behaviour within the UK clothing industry, getting the perspective of people from other countries would taint the veracity of the study results.

Given the level of scrutiny implemented by the researcher when it comes to the research subjects that will be recruited, it is expected that the results of the study should be sufficiently accurate. Do note though that since it is the intention of the researcher to analyse the impact of consumer purchasing behaviour in the UK clothing industry, it would be necessary for the research subjects involved to actually have a certain level of knowledge regarding fashion brands. As such, the rather stringent controls placed on the type of research subject that can be recruited is justified and is not indicative of undue manipulation on the part of the researcher.

Study Concerns

This methodology exposes the participants to very little risk since the study is asking them for data that is not private in the least. However, to eliminate all risk, the responses will be kept in an anonymous location. This way, the only way to access the information will be through a procedure that involves the researcher. The project thus observes research ethics in sampling as well as during data collection process.

Deciding on the Questions to be used in the Interviews

The questions for the interviews were based on an evaluation of the research questions and the data and arguments presented in the literature review section. The aim of the researcher was to develop the questions in such a way that they build up on the material utilised in the literature review. Thus, the questions place a heavy emphasis on confirming the data in the literature review to reveal the extent by which celebrities influence developments within the fashion industry as well as the impact of public perception on celebrity endorsements on their buying behaviour (Dolnicar & Grün 2013).

Data Collection Process

The researcher will utilise the views garnered through the surveys collected via surveymonkey.com along with the literature review data in order to develop a sufficient platform from which effective conclusions can be developed involving the research that is being conducted. The data collection process will actually be quite straightforward; the researcher will first ask various known associates to fill out the online form and instruct them to follow the research criteria when it comes to sharing the same survey link to other individuals that they know.

The consent form will of course be included each time. By asking permission prior to the data collection procedure, this ensures that the researcher follows proper ethical research protocols. The surveys will be filled out individually by the research subjects to ensure its alignment with the aforementioned anonymity of the study results. It will also be necessary to assure the participants of the safe storage of information. This is being done by the research since it was determined that responses will be more favourable if there are assurances of anonymity and identity protection.

Evaluating the Questionnaire Responses

Two methods may be used to score the test, raw score and relative. Both will be used for comparison in the study. The raw score method is a simple sum of the responses within each scale. This involves merely examining which responses seem similar to each other or which are widely divergent. The relative scoring method compares scales for relative contribution to the overall score. The relative proportion for each scale is found by dividing the individual mean score for the scale by the combined means for all scales.

Ethical Considerations

Possible ethical considerations that may arise through this study consist of the following:

- The potential for unintentional plagiarism through direct copying of information.

- The use of nonacademic resources.

- The use of a biased viewpoint on issues which may result in an alteration of the questionnaire results.

- Presentation of data without sufficient evidence.

- Falsifying the results of the research

- Using views and ideas without giving due credit to the original source.

The researcher will endeavor to follow proper academic standards when it comes to the research process and will avoid all the aforementioned ethical considerations that were mentioned.

Analysis

Evaluating Question 1

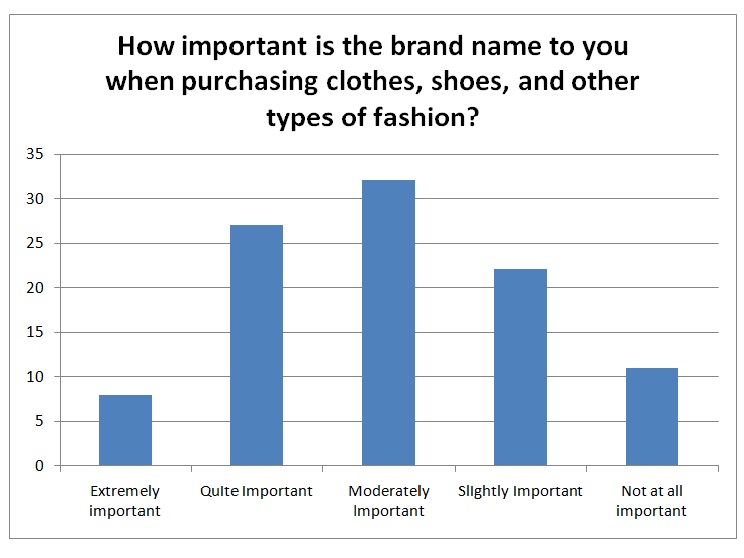

The first question of the survey analysed the importance of brand names to consumers when it came to purchasing clothes, shoes, etc. The survey showed that only 8% of those that responded were oriented towards brands being extremely important towards their choice of apparel. However, a trend in the data was seen which showed that 59% of the respondents placed a considerable level of importance on brands being a deciding factor when it comes to their choice of apparel. Only 33% of those that were evaluated indicated that brands were not as important when it comes to their choice of what to wear. The data thus shows that 67% of those polled focused on the brand name of a product. This helps to support the initial assumptions made in this paper which indicated that brand image did play a considerable role in influencing consumer decisions regarding fashion choices.

Evaluating Question 2, 3 and 4

The following questions were utilised to gauge the overall capacity of consumers to associate popular brands with their favourite celebrities:

- When you think of a fashion brand, what brands come to mind? (Please limit it to three brands)

- Who are your favourite celebrities? (Please limit it to three celebrities)

- What fashion brands come to mind when you think of your favourite celebrities? (Please limit it to three brands)

Consumers were first asked to think of brands that came to mind, then they were asked to think of their favourite celebrities, and afterwards they were asked to associate their celebrities with their respective endorsement deals. The purpose of utilizing this type of question was to gauge the capacity of brand image to exist outside of the context of celebrity endorsements. This was an examination to determine if consumers had a preconceived notion of brand image being associated with celebrities or if there was a separate notion that was apparent. In layman’s terms, this half of the experiment sought to determine whether celebrities were an integral aspect of the concept of brand image associated with the UK clothing industry or if they were a completely independent factor.

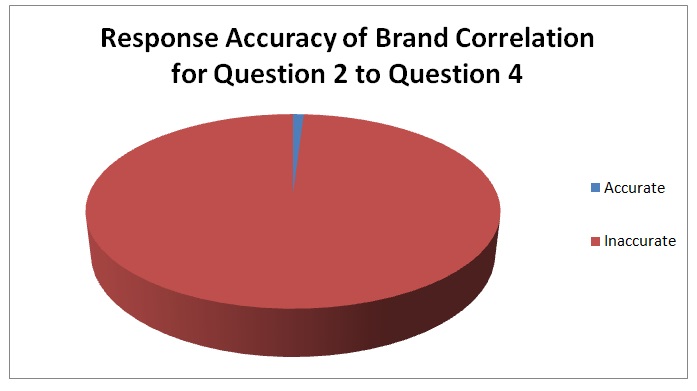

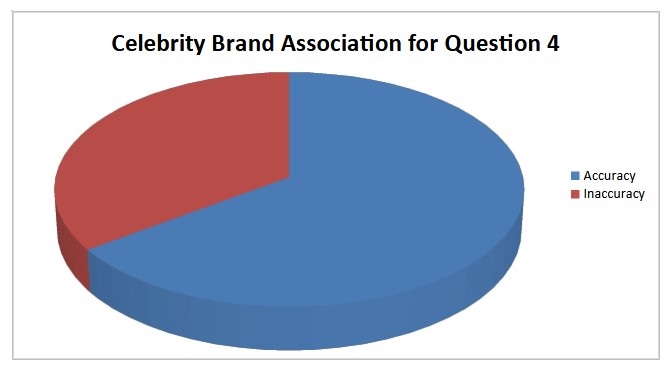

The findings of the study showed that were was a 65% accuracy rate when it came to brand association between celebrities and their respective endorsement deals (a simple Google search to compare each celebrity given with the endorsements they were supposedly associated with), however, when comparing the initial brands that came to mind for the respondents, it showed that there was a 99% inaccuracy rate wherein the brands that were stated initially had no correlation with the brands that were being endorsed by celebrities.

Furthermore, when comparing the results from question 2 to those in question 3, there was no correlation as well with the celebrities that were mentioned. This aspect of the study shows that while consumers are aware of what type of fashion products celebrities are endorsing, they already have a preconceived notion of different brand images that is independent from celebrity endorsements. If there was a dependence factor, it would have shown up as the initial brands being stated being the same as those being promoted by celebrities, however, this was not the case. Based on this result, it can be stated that while celebrity endorsement deals do help in promoting a product, they are not necessarily an integral part of developing the brand image of a company.

Evaluating Question 5

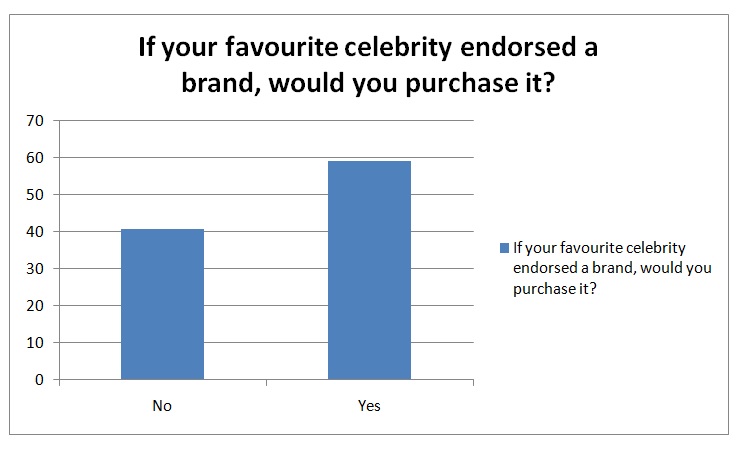

The results of question 5 support the assumptions formulated from questions 2, 3 and 4 wherein it can be seen that 59.18% of the respondents would not buy a product if it was endorsed by their favourite celebrity while 40.82% said that they would. What this result shows is that while celebrity endorsements are effective to a certain extent in popularising a particular brand image, the fact remains that a large percentage of consumers are willing to purchase a fashion brand that is not being endorsed by a celebrity that they know.

Evaluating Question 6

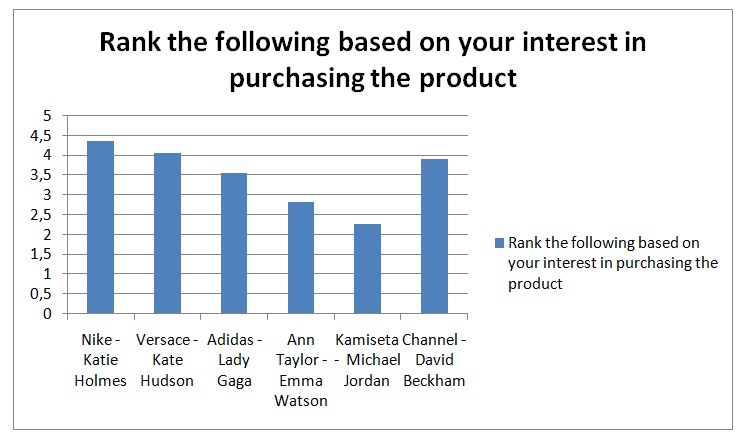

This section tests whether it is the brand image or the celebrity promoter that would cause people to purchase the product. There is an ongoing idea that some brands are inherently more popular based on the type of celebrities that are endorsing it despite the quality or price of the product. (The bigger the celebrity, the more likely people will purchase the product regardless of the price or the type of product being sold). In order to prove or disprove this assertion, this section first devised a set of original endorsements of popular fashion accessories and then mixed up the original endorsers with each other. The result is a list that has celebrity endorsers that normally have absolutely nothing to do with the company’s they are now under.

Original endorsements

- Nike – Michael Jordan

- Ann Taylor – Kate Hudson

- Adidas – David Beckham

- Channel – Emma Watson

- Kamiseta – Katie Holmes

- Versace – Lady Gaga

Altered Fake Endorsements

- Nike – Katie Holmes

- Versace – Kate Hudson

- Adidas – Lady Gaga

- Ann Taylor – Emma Watson

- Kamiseta – Michael Jordan

- Channel – David Beckham

The end result of the investigation involving this question is that despite the “star power” that were placed on certain brands such as Michael Jordan, Emma Watson, or Lady Gaga, the brands did not do as well as the three best brands that were utilised, namely: Nike, Versace and Channel. While known within the UK, Adidas, Ann Taylor and Kamiseta are relatively small brands within the UK market and, as such, despite the celebrity endorser attached to them, they did not do as well as compared to relatively small celebrities being attached to better brands.

The false endorsement of Channel and David Beckham was used as the control category for the experiment which revealed high levels of popularity for both the brand and for the celebrity advertising it which was an expected outcome. What this section shows is that regardless of the “star power”, brand image continues to be a dominating factor that supersedes the “star power” of a celebrity endorser. This shows that brand image has a definite impact on influencing consumer purchasing behaviour. The results seen in this portion of the survey help to support the answers derived from questions 2, 3 4 and 5 regarding the effectiveness of brand image over celebrity endorsement.

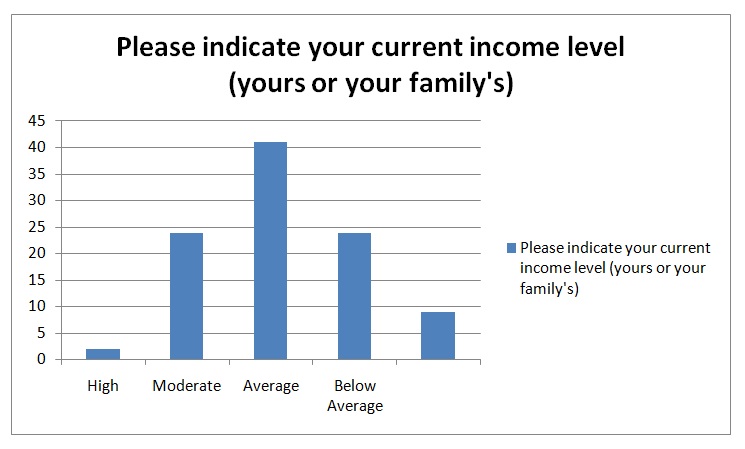

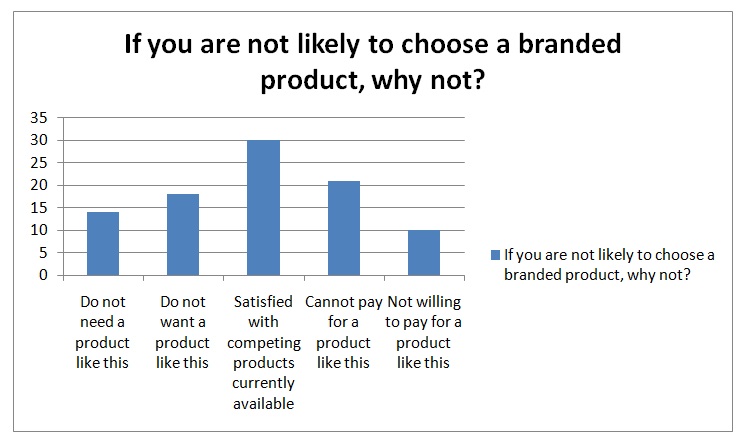

Evaluating Questions 7 and 10

In this section of the work, a comparison was done regarding income levels and the likelihood of people purchasing a branded product. It was revealed that the respondents from moderate, average and below average incomes from question 7 responded that they were unlikely to purchase a brand name piece of clothing since they were either satisfied with what they had, they could not pay for it at the time or were not willing to pay for it at all.

When it comes to consumer purchasing, what must be understood is that based on Maslow’s theory of needs the motivation of consumers to buy certain products tends to change over time and, as a direct result, it would be necessary to for the company to change its method of marketing and sales along with these shifting needs. From this perspective, despite the importance these same respondents placed on brands being the deciding factor when choosing a particular fashion product, the fact remains that their current economic situation is not conducive towards purchasing these items.

This behaviour goes back to the theory of consumer behaviour that was stated within the literature review. From a total utility perspective, consumers of branded goods do indeed derive a considerable level of satisfaction from purchasing this type of product since it makes them feel like they belong to a particular group. However, what you need to take into consideration is the declining marginal utility of each successive purchase and how people would react when confronted with the concepts of price, budget constraints and rational behaviour.

While the first purchase would make consumers feel great, those who are under price and budget constraints would experience a declining marginal utility for each successive item bought since it is eating away at their budget that could have gone towards their own personal lives (i.e. paying bills, rent, etc.). It is due to this that the concept of rational behaviour kicks in wherein despite their desire to purchase more of a fashion brand, they are thus unlikely to do so within the immediate future.

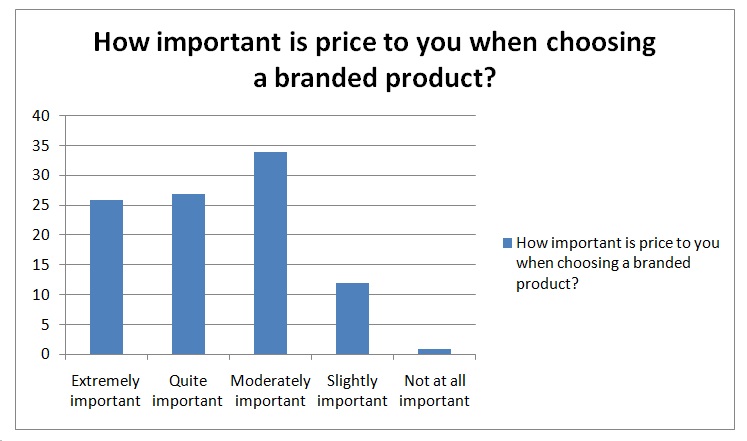

Evaluating Question 8

So far, it has been shown that while brand image considerably influences the buying behaviour of consumers, aspects related to the four fundamental concepts of consumer choice and the theory of consumer behaviour helps to mitigate the capacity of brand image to cause higher amounts of sales. Based on the results of question 9, it can be seen that price is the fundamental concept of consumer choice that is at the forefront of turning people away from a brand name good. This particular conclusion is actually quite obvious given the high prices associated with some brand name goods.

Evaluating Question 9

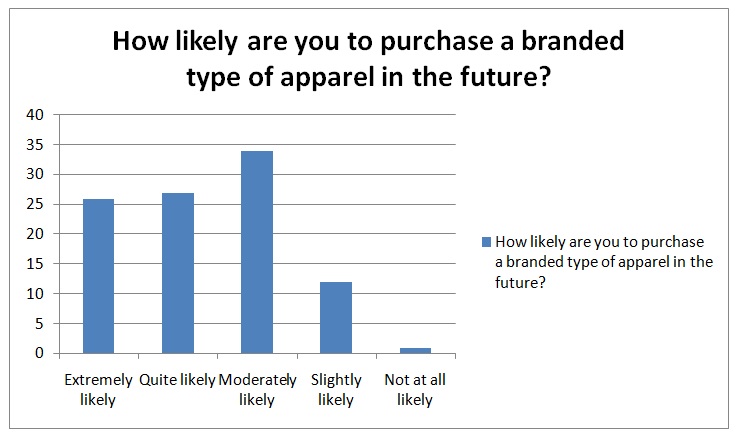

Despite everything involving the four fundamental concepts of consumer choice and the theory of consumer behaviour that has been presented thus far, this analysis concludes with the 9th question which shows that 82 percent of those surveyed are likely to purchase a popular brand name good in the future. What this shows is that the aforementioned constraints on purchasing behaviour that were elaborated on earlier are only temporary and that the demand for brand name goods brought about through brand image continues to be very strong.

Discussion

When examining the data that has been presented so far, the four fundamental concepts of consumer choice must be taken into consideration. In the survey four different kinds of income streams were added namely: high, moderate average, and below average. These levels of income were directly contrasted to decision making process of the customer involving the likelihood of them purchasing a popular brand name fashion item. The survey revealed that the greatest factor in the decision making process for consumers in the UK that was the price of the brand in question and not necessarily the brand itself. This conclusion was developed by comparing the answers of respondents involving the importance of a brand when it came to purchasing shoes, clothes, etc. with their level of income. It showed that those with high to moderate income cared more for the brand as compared to those in lower income classes.

However, the overall answer was that when it came to clothing purchases, customers did place a significant level of importance on the brand a product came from. It should be noted though that this preference conforms to the information stated in the literature review section of the study which stated that consumers are inherently limited to their brand purchases based on price and budget constraints. As such, it is the assumption of this study that as income levels increase the propensity for consumers to purchase popular brand name goods increases, however, when their income decreases this propensity goes down. However, just because this propensity goes down does not mean that the demand for popular brand name goods disappears altogether.

Through the concept of rational behaviour in consumer purchases, it was shown that consumers will react in a logical fashion when it came to their purchases. Thus, despite a consumer desiring to purchase a particular brand name fashion item, they are inherently limited from purchasing it due to the rationale that they need to allocate the money towards other purposes (i.e. food, rent, etc.).

The results of the survey show that there are three particular levels of income that act as majorities in the income selection namely: high, moderate and average which can come to represent the different social classes that exist within the UK (i.e. upper class, middle class, and lower class). When comparing the income classes with the level of importance attributed to brand image, the fact that the importance is the same despite differing income levels shows that brand image can affect the demand side of consumer purchasing behaviour despite limited income levels on one end of the spectrum. This of course goes against the theory of rational behaviour since consumers in this case desire brand name goods despite the fact that they can barely afford it with their income as compared to their higher income counterparts.

One way to understand this behaviour is through the Vroom expectancy theory which explains that consumers can be motivated to buy more and expensive products if there is a sufficient positive correlation between the effort they put into the purchase done and reward they are given. Under this context, since there is an association of luxury goods with wealth and prestige which is the result of the influences of popular culture, it can be stated that the “reward” consumers get in this instance is the association of being well off and rich.

This applies not only to the population set that can afford the brand name products but also those that cannot. This supports the earlier assertions made in this study which stated that consumers “flocked” towards particular brands in order to feel that they “belonged” to a particular group. This means of association with being well off (despite most people not being well off at all) is what drives consumers to purchase particular brand name fashion items since they want to be associated with a particular group of people.

Do note that when comparing the consumers that were concerned about price in the 8th question of the paper with those that were unwilling to purchase a luxury good in the future (the 10th question), it was noted that those who were mostly concerned about price, namely those in the top three choices of extremely important, moderately important and quite important, were the same ones who were unlikely to purchase a brand name good in the future. From a brand image perspective, it can thus be stated that no matter how popular a particular fashion brand is, consumers are still inherently limited by their capacity to purchase that company’s product and thus the brand image of a company only has a limited effect on consumer purchasing behaviour when taking the price of that brand’s products into consideration.

Going into the aspects of the survey that examined the general opinion of UK based consumers regarding their opinions of celebrity backed endorsements; the results showed that nearly 60% of those polled were unlikely to purchase a product if their favourite celebrity were to endorse it. On the other hand, 40% of those surveyed were willing to purchase a product if their favourite celebrity was promoting it. There are several conclusions that can be drawn from this, the first is what was mentioned earlier in the literature review wherein people often identify standards of beauty and appearance based on the celebrities they see on television on a daily basis.

This “standard” as set by celebrities results in consumers patronising particular brands as evidenced by 40 percent of the respondents. Based on the information in the literature review and from the results of the interview, it can be stated that consumers identify pop culture trends and attempt to emulate them as much as possible in order to become more like their celebrity idols. It is desire for emulation that actually drives several aspects of the branded clothing industry within the UK and explains why companies continue to pursue celebrity endorsement contracts. However, this overview does not explain why a vast majority of those that were surveyed said that they would not choose a product if their favourite celebrity endorsed it.

In order to explain why this occurred, it is first important to point out that not all consumers can immediately buy a product. The budget constraints that were brought up earlier need to be taken into consideration and it is due to this that the concept of rational behaviour in purchasing decisions enter into the picture. As explained earlier, most consumers can be thought of as individuals that follow a rational line of thought when it comes to the type of products they buy. As such, if the type of product that a celebrity is endorsing is outside of their price range, then it is unlikely that they would purchase the product. This helps to explain why, despite the endorsements of celebrities, 60% of those that were surveyed were unlikely to purchase a product based on the celebrity endorsement alone.

Further analysis of the data showed that the same people that were unlikely to purchase a product endorsed by a celebrity were also the same ones that placed a higher concern on the price of a product. As such, it can be stated that while brand image is an effective means of getting people to purchase a product, the fact remains that its capacity to do so is limited based on the four fundamental factors of consumer choice which limits the capability of a company’s brand image.

Conclusion

Based on the results of the survey and the concepts of rational behaviour, preference, budget constraints and prices it can be said that brand images can stand alone without celebrity assistance but are inherently limited by price, budget constraints, preferences and the rational behaviour of consumers. Taking this into consideration, it can be stated that the capacity of brand image to influence consumer choice is inherently limited to the type of product that consumers are oriented towards. In the case of fashion brands, this takes the form of the classification of the garment that a particular customer prefers. While brand image can influence consumer choice under the same type of garment line, it has no effect if the consumer wants a completely different type of garment due to price, preference, budget constraints and rational behaviour. This example thus shows the effect that rational choice has on consumer purchasing behaviour in the UK clothing industry and how price and personal choice factor into the type of product that is bought.

Implications

The implications of the study reveal that present day brand image operations that rely on celebrity endorsement may not be as effective as companies believe them to be. A reevaluation is necassary in order to determine whether the high amount paid to celebrities justifies the supposedly postive contribution the association of a brand has towards these celebrities.

Recommendation for Further Study

After analysing the content of the study, it was determined by the researcher that further studies should delve into the difference that brand image has on different cultures. For instance, while this study has delved into the impact of brand image on consumer purchasing behavior within the UK, the results may not be ask applicable when applied to other countries such as Taiwan, the Philippines or Australia. The basis behind this assumption lies in the fact that each country has its own unique culture and, as such, may respond differently to brand images utilised by companies within their respective regions.

Reference List

Agnihotri, R, Kothandaraman, P, Kashyap, R, & Singh, R 2012, ‘Bringing “Social” into Sales: The Impact of Salespeople’s Social Media Use on Service Behaviours and Value Creation’, Journal Of Personal Selling & Sales Management, vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 333-348.

Aggarwal, P, & McGill, A 2012, ‘When Brands Seem Human, Do Humans Act Like Brands? Automatic Behavioral Priming Effects of Brand Anthropomorphism’, Journal Of Consumer Research, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 307-323.

ApeagyeI, PR 2011, ‘The impact of image on emerging consumers of fashion’, International Journal Of Management Cases, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 242-251.

Andzulis, J, Panagopoulos, N, & Rapp, A 2012, ‘A Review of Social Media and Implications for the Sales Process’, Journal Of Personal Selling & Sales Management, vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 305-316.

Anselmsson, J, Bondesson, N, & Johansson, U 2014, ‘Brand image and customers’ willingness to pay a price premium for food brands’, Journal Of Product & Brand Management, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 90-102.

Balabanis, G, & Diamantopoulos, A 2011, ‘Gains and Losses from the Misperception of Brand Origin: The Role of Brand Strength and Country-of-Origin Image’, Journal Of International Marketing, 19, 2, pp. 95-116.

Bane, V, Dubin, D, Gage, E, Singh Gee, A, McIntyre, S, & Murphy, K 2005, ‘Trend of the Week’, People, vol. 64, no. 7, p. 102.

Batra, R, Ahuvia, A, & Bagozzi, R 2012, ‘Brand Love’, Journal Of Marketing, vol. 76, no. 2, pp. 1-16.

Bellezza, S, & Keinan, A 2014, ‘Brand Tourists: How Non–Core Users Enhance the Brand Image by Eliciting Pride’, Journal Of Consumer Research, vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 397-417.

Bellezza, S, & Keinan, A 2014, ‘How “Brand Tourists” Can Grow Sales’, Harvard Business Review, vol. 92, no. 7/8, p. 28.

Bremner, B, & Lakshman, N 2007, ‘India Craves the Catwalk’, Businessweek, vol. 30, no. 12 p. 18.

Beneke, J, Blampied, S, Miszczak, S, & Parker, P 2014, ‘Social Networking the Brand—An Exploration of the Drivers of Brand Image in the South African Beer Market’, Journal Of Food Products Marketing, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 362-389.

Cassidy, H 2003, ‘How the Mighty Have Risen or Fallen’, Brandweek, vol. 44, no. 41, p. 24.

Chunqing, L, Jing, Z, Li, C, & Songling, L 2014, ‘The Brand Image of Customer Loyalty Programs Partnerships in Aircraft Industry Based on Customer Experience. (English)’, Modern Marketing, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 6-9.

Cleeren, K, Van Heerde, H, & Dekimpe, M 2013, ‘Rising from the Ashes: How Brands and Categories Can Overcome Product-Harm Crises’, Journal Of Marketing, vol. 77, no. 2, pp. 58-77.

Colavita, C 2004, ‘British Invasion’, DNR: Daily News Record, vol. 34, no. 1, p. 26.

Correia, S, Veríssimo, Â, & Cayolla, R 2013, ‘The effect of Portuguese Nation Brand on Cognitive Brand Image: Portuguese and Canadian comparison’, International Journal Of Management Cases, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 247-264.

Dall’Olmo, F, Hand, C, & Guido, F 2014, ‘Evaluating brand extensions, fit perceptions and post-extension brand image: does size matter?’, Journal Of Marketing Management, vol. 30, no. 9/10, pp. 904-924.

De Barnier, V, Falcy, S, & Valette-Florence, P 2012, ‘Do consumers perceive three levels of luxury? A comparison of accessible, intermediate and inaccessible luxury brands’, Journal Of Brand Management, vol. 19, no. 7, pp. 623-636.

Dolnicar, S, & Grün, B 2013, ‘Including Don’t know answer options in brand image surveys improves data quality’, International Journal Of Market Research, vol. 55, no. 4, pp. 2-14.

Dolnicar, S, & Grün, B 2014, ‘Including Don’t know answer options in brand image surveys improves data quality’, International Journal Of Market Research, vol. 56, no. 1, pp. 33-50.

Erdogan, B, & Drollinger, T 2008, ‘Endorsement Practice: How Agencies Select Spokespeople’, Journal Of Advertising Research, vol. 48, no. 4, pp. 573-582.

Fang, L, Jianyao, L, Mizerski, D, & Huangting, S 2012, ‘Self-congruity, brand attitude, and brand loyalty: a study on luxury brands’, European Journal Of Marketing, vol. 46, no. 7/8, pp. 922-937.

Ferraro, R, Kirmani, A, & Matherly, T 2013, ‘Look at Me! Look at Me! Conspicuous Brand Usage, Self-Brand Connection, and Dilution’, Journal Of Marketing Research (JMR), vol. 50, no. 4, pp. 477-488.

Fischer, M, Völckner, F, & Sattler, H 2010, ‘How Important Are Brands? A Cross-Category, Cross-Country Study’, Journal Of Marketing Research (JMR), vol. 47, no. 5, pp. 823-839.

Folse, J, Burton, S, & Netemeyer, R 2013, ‘Defending Brands: Effects of Alignment of Spokescharacter Personality Traits and Corporate Transgressions on Brand Trust and Attitudes’, Journal Of Advertising, vol. 42, no. 4, pp. 331-342.

Freund, J, & Jacobi, E 2013, ‘Revenge of the brand monsters: How Goldman Sachs’ doppelgänger turned monstrous’, Journal Of Marketing Management, vol. 29, no. 1/2, pp. 175-194.

Guzmán, F, & Paswan, A 2009, ‘Cultural Brands from Emerging Markets: Brand Image Across Host and Home Countries’, Journal Of International Marketing, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 71-86.

Gwinner, K, & Eaton, J 1999, ‘Building Brand Image Through Event Sponsorship: The Role of Image Transfer’, Journal Of Advertising, vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 47-57.

Han, Y, Nunes, J, & Drèze, X 2010, ‘Signaling Status with Luxury Goods: The Role of Brand Prominence’, Journal Of Marketing, vol. 74, no. 4, pp. 15-30.

Hankinson, G 2012, ‘The measurement of brand orientation, its performance impact, and the role of leadership in the context of destination branding: An exploratory study’, Journal Of Marketing Management, vol. 28, no. 7/8, pp. 974-999.

He, Y, & Lai, K 2014, ‘The effect of corporate social responsibility on brand loyalty: the mediating role of brand image’, Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, vol. 25, no. 3/4, pp. 249-263.

Hede, A, & Watne, T 2013, ‘Leveraging the human side of the brand using a sense of place: Case studies of craft breweries’, Journal Of Marketing Management, vol. 29, no. 1/2, pp. 207-224.

Herstein, R, Gilboa, S, & Gamliel, E 2013, ‘Private and national brand consumers’ images of fashion stores’, Journal Of Product & Brand Management, vol. 22, no. 5/6, pp. 331-341.

Hudders, L, Pandelaere, M, & Vyncke, P 2013, ‘Consumer meaning making’, International Journal Of Market Research, vol. 55, no. 3, pp. 391-4.

Ivens, B, & Valta, K 2012, ‘Customer brand personality perception: A taxonomic analysis’, Journal Of Marketing Management, vol. 28, no. 9/10, pp. 1062-1093.

Jung, H, Lee, Y, Kim, H, & Yang, H 2014, ‘Impacts of country images on luxury fashion brand: facilitating with the brand resonance model’, Journal Of Fashion Marketing & Management, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 187-205.

Kim, J, & Yoon, H 2013, ‘Association Ambiguity in Brand Extension’, Journal Of Advertising, vol. 42, no. 4, pp. 358-370.

Kort, P, Caulkins, J, Hartl, R, & Feichtinger, G 2006, ‘Brand image and brand dilution in the fashion industry’, Automatica, vol. 42, no. 8, pp. 1363-1370.

Kremer, F, & Viot, C 2012, ‘How store brands build retailer brand image’, International Journal Of Retail & Distribution Management, vol. 40, no. 7, pp. 528-543.

Kum, D, Bergkvist, L, Lee, Y, & Leong, S 2012, ‘Brand personality inference: The moderating role of product meaning’, Journal Of Marketing Management, vol. 28, no. 11/12, pp. 1291-1304.

Langlois, J, & Downs, A 1979, ‘Peer Relations as a Function of Physical Attractiveness: The Eye of the Beholder or Behavioural Reality?’, Child Development, vol. 50, no. 2, pp. 409-418.

Lee, H, Lee, C, & Wu, C 2011, ‘Brand image strategy affects brand equity after M&A’, European Journal Of Marketing, vol. 45, no. 7/8, pp. 1091-1111.

Lee, H, Chen, T, & Guy, B 2014, ‘How the Country-of-Origin Image and Brand Name Redeployment Strategies Affect Acquirers’ Brand Equity After a Merger and Acquisition’, Journal Of Global Marketing, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 191-206.

Levy, A 2011, ‘One Picture Is Worth A Thousand Pitches’, Bloomberg Businessweek, vol. 42, no. 40, pp. 39-40.

Lewis, E 2002, ‘Nicked by the fashionistas’, Brand Strategy, vol. 165, p. 16.

Lim, Y, & Weaver, P 2014, ‘Customer-based Brand Equity for a Destination: the Effect of Destination Image on Preference for Products Associated with a Destination Brand’, International Journal Of Tourism Research, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 223-231.

Linyun W., Y, Cutright, K, Chartrand, T, & Fitzsimons, G 2014, ‘Distinctively Different: Exposure to Multiple Brands in Low-Elaboration Settings’, Journal Of Consumer Research, vol. 40, no. 5, pp. 973-992.

Lockwood, L 2004, ‘LF Brands: A Stain on Fashion’s Image?’, WWD: Women’s Wear Daily, vol. 187, no. 10, pp. 2-12.

Lovett, M, Peres, R, & Shachar, R 2013, ‘On Brands and Word of Mouth’, Journal Of Marketing Research (JMR), vol. 50, no. 4, pp. 427-444.

Luo, X, Raithel, S, & Wiles, M 2013, ‘The Impact of Brand Rating Dispersion on Firm Value’, Journal Of Marketing Research (JMR), vol. 50, no. 3, pp. 399-415.

Maehle, N, & Supphellen, M 2011, ‘In search of the sources of brand personality’, International Journal Of Market Research, vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 95-114.

Magnoni, F, & Roux, E 2012, ‘The impact of step-down line extension on consumer-brand relationships: A risky strategy for luxury brands’, Journal Of Brand Management, vol.19, no. 7, pp. 595-608.

Magnusson, P, Krishnan, V, Westjohn, S, & Zdravkovic, S 2014, ‘The Spillover Effects of Prototype Brand Transgressions on Country Image and Related Brands’, Journal Of International Marketing, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 21-38.

Marwick, A 2010, ‘There’s a Beautiful Girl Under All of This: Performing Hegemonic Femininity in Reality Television’, Critical Studies In Media Communication, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 251-266.

Mehta, NK 2012, ‘The Impact of Comparative Communication in Advertisements on Brand Image: An Exploratory Indian Perspective’, IUP Journal Of Brand Management, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 6-3.

Miller, K, & Mills, M 2012, ‘Probing brand luxury: A multiple lens approach’, Journal Of Brand Management, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 41-51.

Mccracken, G 1989, ‘Who Is the Celebrity Endorser? Cultural Foundations of the Endorsement Process’, Journal Of Consumer Research, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 310-321.

Navarro-Bailón, M 2012, ‘Strategic consistent messages in cross-tool campaigns: effects on brand image and brand attitude’, Journal Of Marketing Communications, vol. 18,no. 3, pp. 189-202.

Naylor, R, Lamberton, C, & West, P 2012, ‘Beyond the “Like” Button: The Impact of Mere Virtual Presence on Brand Evaluations and Purchase Intentions in Social Media Settings’, Journal Of Marketing, vol. 76, no. 6, pp. 105-120.

Newman, G, & Dhar, R 2014, ‘Authenticity Is Contagious: Brand Essence and the Original Source of Production’, Journal Of Marketing Research (JMR), vol. 51, no. 3, pp. 371-386.

‘Octagon and Premier Management Define Terms of Endorsement’ 2005, Nutrition Business Journal, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 26-27.

Patton, T 2006, ‘Hey Girl, Am I More than My Hair?: African American Women and Their Struggles with Beauty, Body Image, and Hair’, NWSA Journal, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 24-51.

Pina, J, Iversen, N, & Martinez, E 2010, ‘Feedback effects of brand extensions on the brand image of global brands: a comparison between Spain and Norway’, Journal Of Marketing Management, vol. 26, no. 9/10, pp. 943-966.

Rae, S 1997, ‘How celebrities make killings on commercials’, Cosmopolitan, vol. 222, no. 1, p. 164.

Rajagopal 2011, ‘Consumer culture and purchase intentions toward fashion apparel in Mexico’, Journal Of Database Marketing & Customer Strategy Management, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 286-307.

Romaniuk, J, Bogomolova, S, & Riley, F 2012, ‘Brand Image and Brand Usage’, Journal Of Advertising Research, vol. 52, no. 2, pp. 243-251.