Literature Review

Introduction

This section of the report contains a review of previous research works that have explored the study topic. Particularly, the articles sampled in this review highlight the role of student attitudes towards educational tourism, differences in law between the UK and China, their impact on educational programs and the effects of high costs of education on educational tourism.

However, before delving into the details of these areas of analysis, it is vital to note that this literature review is contextualised within the main tenets of the research questions, which focus on investigating trends in Chinese and British educational tourism, understanding the effects of intrinsic factors (such student motivation) on educational tourism, examining the role of external conditions, such as social conditions and legal framework, on educational tourism in China and the UK and identifying possible solutions that would improve educational tourism standards in the United Kingdom (UK) and China. The first area of analysis centres on understanding the attitudes of Chinese and British Students towards educational tourism.

Attitudes of Chinese and British Students towards Educational Tourism

Educational tourism is partly a product of student attitudes towards learning and their experiences in the classroom setting (Muthanna & Miao 2015). However, this area of research has been poorly explored because of the inadequacy of research studies to understand its implicit attributes, such as student motivation. However, overriding this concern is the belief that seeking overseas education would improve the learning outcomes of students who engage in educational tourism and by extension, the opportunities to advance their careers (Özoğlu, Gür & Coşkun 2015). These beliefs and perceptions about learning could be influenced by several factors relating to the learning environment but culture is deemed one of the primary forces of influence (Gavin 2018; Yuan 2018).

Culture affects student perceptions about educational tourism, including what they deem useful to their educational pursuits, or not (Gavin 2018; Yuan 2018). Although largely seen to be positive, student attitudes encompass different emotions relating to the learning process, including their behaviours and values (Muthanna & Miao 2015). In turn, their thinking patterns and behaviours are influenced by the same force (culture) and their learning outcomes shaped through their interactions with it. Based on the influences of these attitudes on student learning outcomes, the success of educational tourism largely depends on the beliefs about travelling abroad to seek quality education, as opposed to the acquisition of specific knowledge that relates to it (Gavin 2018; Yuan 2018).

Several research studies have pointed out that students’ attitudes could significantly affect the outcomes of educational tourism by influencing the willingness of learners to acquire new knowledge and respond to associated challenges (Perry, Lubienski & Ladwig 2016; Auger, Abel & Oliver 2018; Burton, Ma & Grayson 2017). Therefore, their level of engagement and interest in educational tourism could be significantly affected by the same factors. Without a personal initiative to learn, it is increasingly difficult for students to perform well in any capacity of educational tourism (Auger, Abel & Oliver 2018).

While positive attitudes could empower students to take bold steps in promoting their educational tourism goals, negative attitudes also have the same effect because they make students fearful and anxious about studying in foreign lands (Landon et al. 2017; Siraprapasiri & Thalang 2016). Consequently, they are prevented from witnessing the rich experiences of learning broad and are inhibited from using any of the tools that would improve their learning outcomes (Perry, Lubienski & Ladwig 2016).

In line with this view, studies have shown that students who suffer from negative attitudes about educational tourism often exhibit diminished morale, boredom, or low levels of participation in educational tourism (Landon et al. 2017; Siraprapasiri & Thalang 2016).

In this context of analysis, it should be noted that negative student attitudes not only prevents students from enjoying the benefits of educational tourism but also discourages those who have the ability to do so from enjoying the same benefits because of their inability to use their full capabilities. Research studies have also shown that the opposite is true because students who have a positive attitude towards educational tourism are easily engaged in the process of learning and motivated to excel in it because they find the linked learning processes enjoyable or valuable to their foreign learning experiences (Bacon 2016; Perry, Lubienski & Ladwig 2016; Auger, Abel & Oliver 2018; Burton, Ma & Grayson 2017).

For example, research studies have explored how the attitudes of Chinese students towards learning in English influence their learning experiences and willingness to participate in educational tourism (Lu, Woodcock & Jiang 2014; Zhai, Gao & Wang 2019). Therefore, those who have a positive attitude towards learning English have a higher probability of engaging in educational tourism compared to those who have a negative attitude. Again, as highlighted in this document, such differences are intrinsic and may vary across different jurisdictions or even personalities.

A study by Yuan (2018) and Bislev (2017), which investigated student attitudes about cultural themes, suggested that most Chinese students were willing to learn about their cultural themes first before international ones. This view highlights the quest by Chinese students to seek their own local understanding of education before attempting to understand an international one. For example, attitudes towards English learning are deemed to align with international standards for developing education curriculum because of its global nature (Lu, Woodcock & Jiang 2014; Zhai, Gao & Wang 2019). Therefore, those who are interested in learning the language have better chances of succeeding in educational tourism compared to those who do not (Lu, Woodcock & Jiang 2014; Zhai, Gao & Wang 2019).

Studies that have explored the attitudes of Chinese and British students towards educational tourism suggest that there are more commonalities among both sets of students than there are differences in their attitudes towards educational tourism (Bacon 2016; Perry, Lubienski & Ladwig 2016; Auger, Abel & Oliver 2018; Burton, Ma & Grayson 2017).

For example, a study by Cozart and Rojewski (2015) showed that both groups of students liked beach holidays and preferred to relax after school by engaging in recreational activities. In this regard, both sets of students do not view educational tourism as a pure learning process but also an opportunity for recreation. Studies have also shown that both British and Chinese students are enthusiastic about visiting and learning in new environments or taking part in the local culture of foreign communities (Lin 2019; Lubienski & Ladwig 2016; Auger, Abel & Oliver 2018).

Alternatively, some studies have shown that there are significant differences between the British and Chinese students regarding their intentions to participate in educational tourism (Perry, Lubienski & Ladwig 2016; Auger, Abel & Oliver 2018; Burton, Ma & Grayson 2017).

Notably, it has been observed that the Chinese are interested in learning about other cultures and visiting historical sights, while their English counterparts look forward to enjoying recreational activities and having fun through educational tourism (Lubienski & Ladwig 2016; Auger, Abel & Oliver 2018; Burton, Ma & Grayson 2017). These differences are seen to supersede gender differences because they are rooted in long-standing cultural beliefs associated with eastern and western lifestyles (Lubienski & Ladwig 2016; Auger, Abel & Oliver 2018; Burton, Ma & Grayson 2017).

Differences in Law and their Impact on Educational Tourism among Chinese and British Students

Different countries have unique legal systems that affect different aspects of their social, political and economic growth (Guo, Li & Yu 2017). Particularly, there is a difference in the manner western and Eastern countries, such as China, design their laws and use them to further their educational agenda (Cozart & Rojewski 2015). These laws significantly influence different areas of educational tourism, including travel, visa status and even residency programs (Guo, Li & Yu 2017).

The Chinese law is based on Confucianism and it emphasises the need to respect the morality of legal actions more than the law that underpins it (Anshu, Lachapelle & Galway 2018). This line of reasoning discourages authorities from imposing strict judgements or harsh punishments on offenders and instead encourages them to reform, as a more permanent way of instituting change not only in education but also other aspects of life as well. In this regard, the Chinese believe that the administration and adjudication of laws touching on different aspects of educational tourism need to be analysed through a moral but not a legal lens (Zhang & Lovrich 2016).

Stated differently, the realisation of social order is best achieved through moral persuasion, as opposed to the implementation of legal clauses of law (Anshu, Lachapelle & Galway 2018). Therefore, the law is there only to complement the process of educational tourism and not to initiate it or be an end unto itself. Again, this application of law stems from Confucianism, which emphasises the need to maintain strong social relationships in the society (Cozart & Rojewski 2015). Each type of relationship between a person of authority and his or her subjects (say a father and son) has its own unique merits and context that has to be respected when exercising principles of law.

It is important to understand the implications of law when analysing educational tourism between China and the UK because they have a strong implication on existing policies about travel, residency and the development of educational curriculum (Byrne 2017). For most parts of the last two decades, both China and Britain have made significant changes to their Legal systems to encourage international students to seek education services in their countries (Lang 2018; Yuval-Davis, Wemyss & Cassidy 2018).

For example, the UK recently announced a change in its law to allow foreign students who have graduated from local universities to stay in the UK for up to two years (Tuner 2019). Previously, they were only allowed to stay for four months after graduation (Tuner 2019). The move is speculated to be aimed at increasing the demand for education by international students (Tuner 2019).

Visa stipulations affecting international students in the UK are only a small part of the wider sets of laws that students have to comply with before coming to the country. For example, students are required to uphold immigration checks and meet the minimum entry grade requirements for each university or course (Chankseliani 2018). China also has similar laws although its regulations are designed to appeal to the mainstream philosophies of the Chinese government and people (Kubat 2018).

For example, it is mandatory for internationals students to study some aspect of Chinese culture when they enrol in a local university (Lang 2018). China’s laws also prohibit foreign students from engaging in political activities whenever they are in the country. Therefore, students have to only focus on completing their learning programs and stay away from the political systems of the country.

Observers say that some of the legal guidelines described here attempt to create a stronger or firmer political and ideological control over the teaching and learning processes undertaken in China (Lang 2018; Yuval-Davis, Wemyss & Cassidy 2018). The trend has been on-going for a long time and it is informed by the view that some Chinese universities have been operating without much control from the government. In line with this view, there is a consensus among many researchers who have investigated China’s laws on education that the country prefers a legal system that aligns with the current political ideologies of the state (Lang 2018; Yuval-Davis, Wemyss & Cassidy 2018).

However, a broad overview of the country’s laws shows that China has emphasized a lot on culture and language. This is why before admission to some courses, students are required to study some aspects of the Chinese culture.

Although legal changes in Britain and China have made it possible for students from both countries to access international education, some policies have not been fully implemented. Consequently, China has instituted several legal reforms to promote the growth of the sector, including education tourism (Lang 2018; Yuval-Davis, Wemyss & Cassidy 2018). This is why several provinces and jurisdictions still have the leeway to institute additional laws to facilitate educational tourism (Chankseliani 2018). For example, the city of Xi’an allows for tax exemptions to international students who seek education in private universities because the government planned to encourage such higher institutions of education to improve the quality of their education and make it world class (Kubat 2018).

Differences in Educational Costs between Britain and China and their Impact on Educational Tourism

The cost of education has gained prominence in academic circles within the past three decades. Many literatures that have delved into this area of analysis have used different concepts, such as economies of scale and cost structures to explain the impact of higher education costs on student learning outcomes (Schneider & Deane 2015). These discussions have also been conveyed within the general need to improve resource allocation in the higher education sector (Schneider & Deane 2015; Courtney 2019).

The importance of understanding the impact of educational cost structures on student learning outcomes has also been pegged with discussions surrounding the growth of educational tourism because the concept is impacted by the willingness of students to seek affordable educational opportunities overseas (Courtney 2019).

Although the cost of education in Chinese universities is relatively standardized, there is a lot of variation to the amount of money students can pay to access education services in private universities (Schneider & Deane 2015). Comparatively, the cost of education in the US is significantly higher than China. A report by Merola, Coelen and Hofman (2019) suggests that the difference could be more than 50%. The lowest tuition fees paid in US public universities is about $1,500 per year but the average tuition fees is $6,500 for private institutions of higher learning (Kyungpook National University 2019). In some cases, this number could be as high as $9,000 for some universities (Kyungpook National University 2019).

The low tuition costs linked to public universities are often associated with 2-year courses as opposed to 4-year learning programs that take more time to complete and assess (Kyungpook National University 2019). Overall, tuition costs in public universities in the US are significantly lower than those in private universities (Courtney 2019). The tuition fees paid by non-resident students is also significantly high because there is an additional residency fee that foreign students have to pay to authorities (Kyungpook National University 2019). Resident students do not have to pay for this cost.

Cost is often a significant consideration for most foreign students in the US an China because they have to think about tuition and accommodation costs when studying abroad. These concerns have been further extended to the need to understand the future of education because issues about quality and inefficiencies of education services have increased the impetus to understand why cost is an important consideration in promoting educational tourism and sustainability (Schneider & Deane 2015; Courtney 2019).

The problem is not only confined to the education sector because people generally have concerns regarding the implications of an expensive education system on the ability of students to get quality services (Courtney 2019). In the US, such discussions have been contextualised in debates surrounding rising levels of student debt. Similar discussions have been had in the UK (Courtney 2019).

Relative to the above discussions, the revenue theory of cost, as developed by Howard Bowen in the 1980s, has been used to explain financial trends in higher education (Schneider & Deane 2015). This theory suggests that higher institutions of learning often spend most of the resources they have on on-going projects and have little to save (Schneider & Deane 2015). Therefore, whenever, they receive increased resource allocations, their costs also escalate, thereby creating a spiral effect of income and expenditure (Schneider & Deane 2015).

Decades that have seen the application of this theory in practical educational contexts show that many countries have systems that create a strong need for seeking financial resources, which are later absorbed into different school programs that equally demand a lot of money to run (Schneider & Deane 2015).

To address some of the above-mentioned concerns, many countries that have a vibrant education sector are paying attention to education tourism because it helps to boost their economies and improve their existing infrastructure networks (Lee, McMahon & Watson 2018). Doing so generates revenues for the travel industry and indirectly leads to the assimilation of different cultures, thereby makings students more dynamic and responsive to multicultural issues (Lee, McMahon & Watson 2018).

Although educational tourism is widely welcomed by many countries, it only serves a small niche market in tourism and education sectors. The uniqueness of this market means that few researchers have focused on understanding how it works in educational tourism or why students are motivated to travel across borders to get an education. One discourse that has emerged from this investigation is the need to understand the true meaning of the context of analysis.

Studies show that the cost of higher education in China is significantly lower than the UK (Kyungpook National University 2019; Thøgersen 2015). However, the cost of education in China is higher than some European countries (Hahn 2015).

In line with this discussion, it is important to acknowledge that the low cost of education in China is not felt in all parts of the country because the tuition fees associated with pursuing an education in major cities, such as Beijing and Shanghai, is significantly higher than other parts of China (Zhou 2018). The competitiveness of the college admission process in China is part of the reason why some Chinese students leave the country and seek new opportunities for higher education overseas (Hansen 2015). Those that secure a spot in these foreign universities are often forced to pay high tuition fees which could be prohibitive to some people.

Thøgersen (2015) says that analysing the cost of education between China and western countries should be done after acknowledging the cost of living as well. Relative to many western countries, including the US and UK, the cost of living in China is significantly lower than most western countries (Chen & Ross 2015). Therefore, students who study overseas may experience challenges adapting to new expenses. This change in living costs has been prohibitive for many Chinese families who come from low income households.

A report by Courtney (2019) suggests that the cost of education in the UK is significantly higher than most western countries. The article also investigated the cost of higher education in England and found that it was among the highest in the world (Courtney 2019). Notably, the cost of education in the UK was found to be higher than the 25 countries that constitute the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (Courtney 2019).

The US was the only country identified to have similarly high tuition fees. However, its public institutions of learning were identified to be significantly cheaper than similar institutions in the UK (Courtney 2019). Ironically, the same article by Courtney (2019) showed that the net return students get from studying in the UK is significantly lower than most OECD countries.

The cost-benefit analysis of pursuing higher education in the UK and China has been characterised by discussions that focus on the net income students get after graduation (Bacon 2016; Perry, Lubienski & Ladwig 2016; Auger, Abel & Oliver 2018; Burton, Ma & Grayson 2017). Following this school of thought, several studies have shown that the societal benefits of acquiring educational degrees are far less than the cost paid to get them (Bacon 2016; Perry, Lubienski & Ladwig 2016; Auger, Abel & Oliver 2018; Burton, Ma & Grayson 2017).

The situation is worse in China because millions of students who graduate from universities do not get a job (Coates 2015). The situation is further catalysed by heavy investments made by families to pay tuition fees for their sons and daughters (Lai 2015). Therefore, it is not uncommon to find households which have spent a lot of money on educating their children and yet they stay home after graduation because of the lack of employment opportunities.

To address such concerns, the UK educational system has a robust financial support system for needy students. Furthermore, the government often makes significant investments in the education sector to make the fund more impactful and effective (Burton, Ma & Grayson 2017). For example, it is reported that financial investments made in education are the fourth highest in the country (Courtney 2019). Stated differently, the UK has spent about four times its gross domestic product (GDP) on education (Courtney 2019). Therefore, the number of students who suffer from strained financial resources is lesser than China. Broadly, the high tuition fees associated with UK universities is commensurate with the demand for higher education in the country. Indeed, the UK is the second-most sought after destination for educational tourism in the world after the US (Courtney 2019).

Summary

A review of existing literature highlighted in this chapter has shown that several factors affect how educational tourism is practiced in China and the UK. Student attitudes, existing laws and educational costs have emerged as some of the most impactful forces influencing student behaviour in educational tourism. Although the findings mentioned in this chapter are elaborately developed and underpin different facets of educational tourism, the researcher observed that no studies have done a comparative analysis of educational tourism between the UK and China. This gap in research is filled by this study and the methods adopted in addressing the research issue are highlighted in the methodology section below

Methodology

Introduction

This section of the report highlights the methods used by the researcher to address the study topic. Key sections of this chapter highlight the research approach, design, data collection methods, sample population and data analysis techniques used in the study.

Research Approach

According to Coe et al. (2017), there are two major research approaches used in academic research: qualitative and quantitative. The qualitative method is often used to measure subjective variables, while the quantitative technique is for measuring quantifiable data (Uprichard & Dawney 2019). In this study, both techniques were integrated to form a larger mixed methods framework.

The mixed methods approach was used in this study because of the complexity of the research topic (Moseholm & Fetters 2017). This is because educational tourism is a broad concept that conceptualises different aspects of quantitative and qualitative investigations. For example, the legal basis for its implementation, which has been highlighted in the literature review above, is a qualitative issue because of its openness to interpretation. Similarly, the cost of education, which informs travel decisions and student experiences are quantitative concerns that had to be addressed in the study. Therefore, the mixed methods research approach provided a framework for integrating multiple sets of data. Its effectiveness in doing so is highlighted by Snelson (2016).

Research Design

According to Research Rundowns (2019), the mixed methods research framework is characterised by six research designs: sequential explanatory, sequential exploratory, sequential transformative, concurrent triangulation, concurrent nested and concurrent transformative methods. The major point of difference for the aforementioned designs is the order of prioritising the collection of qualitative and quantitative findings.

Based on the merits of each research design and as highlighted by Research Rundowns (2019), the sequential transformative method was used as the main research design. It does not have a preference for the collection of either qualitative or quantitative data. Instead, either method of data collection could be adopted and the overall findings merged at the last stage of data analysis, which is the integration phase (Research Rundowns 2019). This design gives room for the researcher to use the technique that best serves a theoretical perspective.

Data Collection Methods

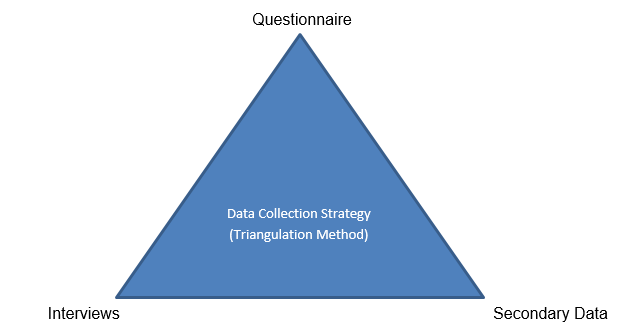

The data collection process was implemented in two phases. The first one was meant to gather views regarding the impact of external factors on educational tourism in China and Britain, while the second one was meant to assess the role of intrinsic factors on educational tourism between the two countries. Data relating to the intrinsic factors affecting educational tourism were gathered using surveys and interviews, as the primary mode of data collection. Alternatively external factors impacting educational tourism were reviewed by assessing secondary research data from reputable books, journals and websites. Collectively, these sources of information formed the triangulation technique of data collection, which was used to collect data, as described by Morgan (2019). Figure 1 below highlights the structure of the data collection strategy.

According to Farrell, Tseloni and Tilley (2016), the triangulation method highlighted above is a robust way of collection data because one set of information could be used to verify the merits of another. For example, secondary research information was used to contextualise the primary data gathered from interviews and questionnaires. Similarly, the primary data obtained created the impetus for the collection of secondary data for verification purposes.

Furthermore, secondary data provided guidance to the researcher to select relevant materials for review. As will be explained in subsequent sections of this chapter, the triangulation strategy was also instrumental in safeguarding the validity of the research findings because of the integration of multiple aspects of data collection. Stated differently, this triangulation method helped the researcher to cross validate the findings and identify patterns or areas of inconsistency that warranted further review. In line with this goal, the main motivation for using the triangulation method was to analyse the topic from different dimensions.

Indeed, as proposed by Suharyanti, Masruroh and Bastian (2017), it was possible to increase the level of knowledge about the research phenomenon and to strengthen the foundation of the research findings because the triangulation method supports a researcher’s views from various standpoints.

Sample Population

As highlighted in this chapter, data was gathered from two perspectives: primary and secondary information. Primary data involved the collection of qualitative information from the respondents using interviews (focus groups) and surveys. Since the interviews were lengthy, only four respondents were selected to participate in the research. Respondents who took part in the study comprised of Chinese or British students who have participated in educational tourism either in China or the UK. However, exception was also made to allow for the recruitment of participants who did not participate in educational tourism in any of the aforementioned two countries.

Similarly, those who studied in the two countries had an opportunity to participate in the study. The use of a small sample size in the research is justified through the works of Sekaran and Bougie (2016), which recommend that interviews should have less than 12 informants. The purpose is to improve the quality of engagement between the researcher and respondents. The small sample of respondents selected to answer the research question also aligns with the techniques used by other researchers to investigate a similar research topic.

For example, Cockrill and Zhao’s (2017) interviewed only five respondents when seeking the views of Chinese students regarding their motivations to participate in education tourism in the UK. The small sample population selected for interviews also mirrors a similar approach taken by Sekaran and Bougie (2016) in conducting focus group discussions because such meetings are often characterised by the involvement of about four people.

Therefore, instead of pressuring the respondents to vote about the specific research issue (as would be the case in many quantitative assessments), the interview process allowed the informants to give their views about the research topic in a relatively relaxed environment. Nonetheless, focus group discussions have been identified to be more effective in data collection than individual interviews because they benefit from the enrichment of data which is created when different people from diverse backgrounds discuss specific research issues (Creswell 2014). However, the main challenge associated with this data collection technique is the lack of control of the research process by the researcher.

Therefore, it is difficult to determine the quality or direction of research that will be generated from the study. Similarly, it is observed that some respondents may be affected by “group thinking” when giving their responses, thereby creating the potential for variations to occur between the views they would give individually and as a group (Creswell 2014).

The stratified random sampling was selected as the main approach for recruiting respondents. In line with the principles of this sampling design, the researcher sorted the respondents’ views based on similar data features, such as gender, age and nationality. After the implementation of the stratified random sampling method, the different respondent groups were later randomly sampled.

This method was adopted because it reduced the possibility of bias during sampling because each group member had an equal chance of being selected (Creswell 2014). Lastly, for the quantitative aspect of the study, the researcher sought the views of 150 respondents to have a broad and representative understanding of the research issue. This approach is in line with the recommendations of Sekaran and Bougie (2016), which suggest that large sample sizes help to improve the reliability and effectiveness of research projects.

Primary Data

Primary data was collected using focus group discussions and questionnaires. According to Garner, Wagner and Kawulich (2016), there are two major types of questionnaires used to collect data in research: interviewer and respondent questionnaire. The interviewer questionnaire involves a direct way of collecting data because it relates to face-to-face interviews, whereby researchers ask direct questions and the respondents give similarly direct responses (Garner, Wagner & Kawulich 2016).

Comparatively, the respondent questionnaire is used in research investigations that high the role of informants as the main drivers of data collection. This type of questionnaire often involves giving respondents an opportunity to answer questions without the direct involvement of the researcher. This method of data collection is often implemented online.

This paper adopted the online questionnaire as the main basis for data collection. Stated differently, information was collected from the respondents when the informants gave their views online. This method of data collection was selected for this study because it gave the respondents adequate freedom of time to give their views. Furthermore, it was difficult to collect information physically as the respondents were dispersed across a large geographical area. The large sample of informants selected to give their views about the research topic also informed the use of online questionnaires because it made the data collection process cost-effective.

One of the main challenges associated with the collection of data using virtual means was the difficulty of responding to the questions posed by the informants on time. Therefore, it can only be assumed that the respondents understood the questions posed and answered them correctly. As will be highlighted in subsequent sections of this chapter, the member-check technique was used to address this challenge.

The questionnaire design for collecting primary research data was categorised into two sections. The first one was focused on collecting demographic data, which involved determining the respondents’ location, age, gender, income, nationality and education levels.

The purpose of collecting this type of information was to understand key characteristics of the researcher and evaluate whether they influenced their views. The second section of the questionnaire sought to finding out the respondent’s experience with educational tourism and whether they had participated in it in the first place. The key pieces of information that were sought in this area of study were the format of participating in educational tourism, the length of time for participation and the number of participants. This second area of assessment was related with the third one because the latter sought to find out detailed activities of educational tourism.

Important pieces of information that were obtained in this manner related to the knowledge students expected to have obtained from participating in educational tourism, the identification of preferred destinations of travel and how long students intended to stay there. Other important data obtained in this manner related to their satisfaction with the services provided in educational tourism and the affordability of the same services.

The last part of the questionnaire was open-ended because it sought to find out the respondents’ views regarding educational tourism. These questions were open-ended and appealed to the qualitative aspect of this analysis. The researchers were also required to state why they chose to participate in educational tourism in this section of the questionnaire. The complete document was posted online for the informants to access. The simple design of the questionnaire allowed the respondents to complete it in less than 15 minutes.

As highlighted in this report, the interview technique was the second method of collecting primary data. The interviews were semi-structured because it helped the researcher to have open discussions about the research topic but in a formal way. The small number of respondents included in the study made it possible to interview all the informants in the group. Therefore, data was collected from a focused group perspective.

According to Jenkinson et al. (2019), groups of less than ten people who want to discuss a topic or product launch fit the description of focus groups. The main justification for using this data collection method was its ability to measure students’ attitudes towards educational tourism. The focus group discussion also provided the researcher with an opportunity to save time in collecting data because it would be tedious to undertake all four interviews separately.

Therefore, it was simpler to conduct have the four interviews in one sitting. However, Lijadi and van Schalkwyk (2015) say that focus group discussions are often abstract because the respondents do not spend a lot of time explaining their views. Another disadvantage associated with this technique is moderator bias because it has been observed that researchers could influence the direction of the discussions by asking leading questions (Jenkinson et al. 2019; Lijadi and van Schalkwyk 2015). These challenges were addressed in this study by making sure the discussion remained objective to the research topic.

To guide the focus group discussion, the researcher followed a guideline for asking the research questions but had the freedom to deviate from the main line of questioning if there was a need to do so. Therefore, not all the questions asked were framed before the interviews were conducted because some of them were simply created during the interviews. In this manner, both the researcher and interviewees had the freedom to delve into the conversations more in-depth, as opposed to a rigid interview framework that leaves little room for deviation. Compared to this technique, Creswell (2014) says that the interview method requires careful thought and planning.

The need to do so was recognised in this study when developing the research questions because the researcher carefully thought about the questions before-hand, thereby creating the opportunity to undertake the probing process formally. One of the major justifications for using the semi-structured interview method was its ability to allow for a two-way communication between the researcher and respondents (Creswell 2014).

The use of semi-structured interview was also informed by a similar use of the technique by other researchers who have investigated a related research issue. For example, Abubakar, Shneikat and Oday (2014) used the semi-structured interview method to identify the main factors influencing educational tourism. His sample population was comprised of 31 respondents who provided comprehensive views on the research topic.

Secondary Data

As highlighted in this chapter, secondary data was sought as a complementary method of data collection. It was meant to contextualise the findings within the body of existing literature to find out whether they merged or diverged with the existing body of knowledge surrounding educational tourism in China and the UK. Emphasis was made to source credible and reliable published information by sampling articles or websites that were published within the last five years (2014-2019). The justification for doing so was to receive updated information on the research topic. This need was informed by the importance of understanding the latest trends in educational tourism among British and Chinese students.

Articles whose publication dates are older than five years may fail to capture such trends. Therefore, the sources of secondary data were limited to a five-year publication time frame because the researcher intended to get updated information. The secondary data collected in this manner were mostly confined to educational materials contained in books, journal and credible websites. These three sources of data were selected for use in the investigation because they are credible and reliable (Creswell 2014). Indeed. As highlighted by Sekaran and Bougie (2016), these three sources of information have been extensively used in academic circles as credible sources of research information.

Data Analysis Methods

As mentioned in this study, three sets of data were generated from this study. The first one was qualitative information and it was generated from focus group discussion involving a select group of students who had participated in educational tourism within china and the UK. The second set of data (quantitative) was obtained using questionnaires that were filled online by a group of 150 students. The third set of data was obtained from secondary research. Its purpose was to be a platform for comparing the current findings with historical information on the research topic. Consequently, the researcher was able to identify areas of commonalities or divergence of opinions between the study’s findings and existing research. Each method of data collection had its own data analysis plan. They are discussed below.

Qualitative Data

To recap, qualitative information was obtained through focus group discussions. The data generated was through interviews, which were subjective in nature. Consequently, there was a need to analyse this type of data using the thematic and coding method that identified patterns in responses and transforming them into key themes (Nowell et al. 2017). According to Nowell et al. (2017), the thematic and coding method has six key steps of data analysis, which include:

- familiarising the researcher with data,

- generating initial codes of analysis,

- searching for themes,

- reviewing themes,

- defining themes and developing the final report.

The main justification for using the thematic method of data analysis in this study is its flexibility. Particularly, its ability to accommodate different types of theories gave room to the researcher to interpret the findings in an open manner.

Quantitative Data

The Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences (SPSS) was used as the main data analysis software for the quantitative data. It is a software package that has been used by several researchers to handle large volumes of data (McCormick & Salcedo 2017). This ability was the motivation for using it in this research process because there were 150 responses that had to be analysed. The SPSS method was also appropriate for this study because the researcher had the necessary technical skills of operating such a software.

This recommendation stems from the views of McCormick and Salcedo (2017), which suggest that SPSS users have to have the necessary skills needed to operate the software. Another justification for using the SPSS technique is its proven record in managing complex statistical data analysis procedures (Denis 2018). Its efficacy in this regard has been demonstrated by market researchers, data miners and other professionals who have used it to undertake different levels of statistical analyses (McCormick & Salcedo 2017).

However, the use of the SPSS software to analyse quantitative data was limited to descriptive analysis techniques, which helped to espouse the key characteristics of the data mined. Therefore, key features of the statistics that were generated from the data included (but were not limited to mean, frequencies and standard of deviation). These different characteristics of the data helped the researcher to make sense of the quantitative findings and ultimately link them to the research questions.

Secondary Data

As highlighted in this study, secondary data was one of the main sources of information in the study. It helped to contextualise the findings and identify areas of data convergence or divergence, relative to the findings of other researchers who have done similar investigations. Dozens of articles were analysed within this research framework using the thematic and coding method, as described in the qualitative section of data analysis above.

Ethical Considerations

The ethical considerations of a study refer to the duty to do what is right in the course of undertaking a research project (Creswell 2014). As with other types of research that involve human subjects, the need for conducting the investigation ethically was paramount. It was informed by the importance of protecting the rights of respondents when they give out their views about a research topic (Creswell 2014).

In line with this practice, the researcher sought ethical approval from the university by completing the ethical form of the faculty of study. Since the process of data collection was relatively straightforward and did not focus on collecting the views of organisations, there was no need to seek additional ethical approval from an external agency. As part of the institutional regulations governing research projects on international tourism and hospitality management, the researcher made sure that the ethical guidelines proposed in this study conformed to the Cardiff Met Research Governance Framework.

This model mandates researchers to follow high standards of academic practice and honesty in the process of conducting educational research. Key principles underpinning this framework include honesty, responsibility, honesty, acknowledge, rigor and sustainability. Lastly, the researcher also complied with Cardiff Met requirements on confidentiality and anonymity by protecting the identities of the respondents when presenting the final report. This ethical practice was intended to allow the informants to speak freely without the fear of reprisals. This principle also prevented the researcher from disclosing any aspect of the research investigation without prior approval from the university or respondents.

Reliability and Validity of Findings

The reliability and validity of the findings presented in this study were safeguarded by the implementation of the member-check technique. This strategy allowed the researcher to share the study findings with the respondents to make sure that the information conveyed in the final report represented their original views (Management Association and Information Resources 2019).

The member-check technique has been supported by research institutions, such as the Management Association and Information Resources (2019), which have demonstrated its efficacy in improving the credibility, validity, reliability and transferability of research data. Its effectiveness in improving the quality of interview findings has also been highlighted by researchers, such as Burton (2017). Nonetheless, the ability to develop quality findings based on its merits depends on a researchers’ ability to develop rapport with the respondents and obtain open and honest feedback.

Summary

As highlighted in this chapter, the mixed methods research approach was used as the overriding framework for this investigation. It gave room for the researcher to integrate qualitative and quantitative findings using the sequential transformative design. The quantitative investigation sampled the views of 150 participants who were students that had participated in educational tourism in China or Britain, while the qualitative findings were developed from focus group discussions that involved four informants. Their findings were assessed using the SPSS method and thematic techniques. Lastly, ethical approval was sought from the researcher’s university.

Reference List

Abubakar, A., Shneikat, B & Oday, A 2014, ‘Motivational factors for educational tourism: a case study in Northern Cyprus’, Tourism Management Perspectives, vol. 11, no. 1, pp.58-62.

Anshu, S, Lachapelle, F & Galway, M 2018, ‘The recasting of Chinese socialism: the Chinese new left since 2000’, China Information, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 139-159.

Auger, RW, Abel, NR & Oliver, BM 2018, ‘Spotlighting stigma and barriers: examining secondary students’ attitudes toward school counseling services’, Professional School Counseling, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 1-10.

Bacon, DR 2016, ‘Reporting actual and perceived student learning in education research’, Journal of Marketing Education, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 3-6.

Bislev, A 2017, ‘Student-to-student diplomacy: Chinese international students as a soft-power tool’, Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, vol. 46, no. 2, pp. 81-109.

Burton, SL (ed.) 2017, Engaged scholarship and civic responsibility in higher education, IGI Global, New York, NY.

Burton, WB, Ma, TP & Grayson, MS 2017, ‘The relationship between method of viewing lectures, course ratings, and course timing’, Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 1-10.

Byrne, B 2017, ‘Testing times: the place of the citizenship test in the UK immigration regime and new citizens’ responses to it’, Sociology, vol. 51, no. 2, pp. 323-338.

Chankseliani, M 2018, ‘Four rationales of HE internationalization: perspectives of U.K. universities on attracting students from former Soviet Countries’, Journal of Studies in International Education, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 53-70.

Chen, Y & Ross, H 2015, ‘Creating a home away from home: Chinese undergraduate student enclaves in US higher education’, Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 155-181.

Coates, J 2015, ‘Unseeing Chinese students in Japan: understanding educationally channelled migrant experiences’, Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 125-154.

Cockrill, A & Zhao A 2017, ‘The UK as an Educational Tourist Destination: Young Chinese’ experiences of the UK’, In: CL Campbell (ed.) The customer is not always right? Marketing orientations in a dynamic business world, Springer, Cham, pp. 885-886.

Coe, R, Waring, M, Hedges, LV & Arthur, J 2017, Research methods and methodologies in education, SAGE, London.

Courtney, S 2019, ‘Higher education in England among world’s most expensive, report says’, Metro. Web.

Cozart, DL & Rojewski, JW 2015, ‘Career aspirations and emotional adjustment of Chinese international graduate students’, SAGE Open, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 1-10.

Creswell, JW 2014, Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches, SAGE, London.

Denis, DJ 2018, SPSS data analysis for univariate, bivariate, and multivariate statistics, John Wiley & Sons, London.

Farrell, G, Tseloni, A & Tilley, N 2016, ‘Signature dish: triangulation from data signatures to examine the role of security in falling crime’, Methodological Innovations, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1-10.

Garner, M, Wagner, C & Kawulich, B (eds) 2016, Teaching research methods in the social sciences, Routledge, London.

Gavin, NT 2018, ‘Media definitely do matter: Brexit, immigration, climate change and beyond’, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 827-845.

Guo, Q, Li, Y & Yu, S 2017, ‘In-law and mate preferences in Chinese society and the role of traditional cultural values’, Evolutionary Psychology, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 1-10.

Hahn, CL 2015, ‘Teachers’ perceptions of education for democratic citizenship in schools with transnational youth: a comparative study in the UK and Denmark’, Research in Comparative and International Education, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 95-119.

Hansen, AS 2015, ‘The temporal experience of Chinese students abroad and the present human condition’, Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 49-77.

Jenkinson, H, Leahy, P, Scanlon, M, Powell, F & Byrne, O 2019, ‘The value of group work knowledge and skills in focus group research: a focus group approach with marginalized teens regarding access to third-level education’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, vol. 18, no. 9, pp. 1-10.

Kubat, A 2018, ‘Morality as legitimacy under Xi Jinping: the political functionality of traditional culture for the Chinese communist party’, Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 47-86.

Kyungpook National University 2019, The cost of studying at a university in China. Web.

Lai, H 2015, ‘Engagement and reflexivity: approaches to Chinese-Japanese political relations by Chinese students in Japan’, Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 183-212.

Landon, AC, Tarrant, MA, Rubin, DL & Stoner, L 2017, ‘Beyond “just do it”: fostering higher-order learning outcomes in short-term study abroad’, AERA Open, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 1-10.

Lang, B 2018, ‘Authoritarian learning in China’s civil society regulations: towards a multi-level framework’, Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 147-186.

Lee, MC, McMahon, M & Watson, M 2018, ‘Career decisions of international Chinese doctoral students: the influence of the self in the environment’, Australian Journal of Career Development, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 29-39.

Lijadi, AA & van Schalkwyk, GJ 2015, ‘Online Facebook focus group research of hard-to-reach participants’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 1-10.

Lin, J 2019, ‘Be creative for the state: creative workers in Chinese state-owned cultural enterprises’, International Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 53-69.

Lu, J, Woodcock, S & Jiang, H 2014, ‘Investigation of Chinese university students’ attributions of English language learning’, SAGE Open, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 1-10.

Management Association and Information Resources (ed.) 2019, Civic engagement and politics: concepts, methodologies, tools, and applications: concepts, methodologies, tools, and applications, IGI Global, New York, NY.

McCormick, K & Salcedo, J 2017, SPSS statistics for data analysis and visualization, John Wiley & Sons, London.

Merola, RH, Coelen, RJ & Hofman, WH 2019, ‘The role of integration in understanding differences in satisfaction among Chinese, Indian, and South Korean international students’, Journal of Studies in International Education, vol. 23, no. 5, pp. 535-553.

Morgan, DL 2019, ‘Commentary after triangulation, what next?’, Journal of Mixed Methods Research, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 6-11.

Moseholm, E & Fetters, MD 2017, ‘Conceptual models to guide integration during analysis in convergent mixed methods studies’, Methodological Innovations, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 1-10.

Muthanna, A & Miao, P 2015, ‘Chinese students’ attitudes towards the use of English-medium instruction into the curriculum courses: a case study of a national key university in Beijing’, Journal of Education and Training Studies, vol. 3, no. 5, pp. 59-69.

Nowell, LS, Norris, JM, White, DE & Moules, NJ 2017, ‘Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 1-10.

Özoğlu, M, Gür, BS & Coşkun, I 2015, ‘Factors influencing international students’ choice to study in Turkey and challenges they experience in Turkey’, Research in Comparative and International Education, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 223-237.

Perry, LB, Lubienski, C & Ladwig, J 2016, ‘How do learning environments vary by school sector and socioeconomic composition? Evidence from Australian students’, Australian Journal of Education, vol. 60, no. 3, pp. 175-190.

Research Rundowns 2019, Mixed methods research designs. Web.

Schneider, M & Deane, KC 2015, The university next door: what is a comprehensive university, who does it educate, and can it survive? Teachers College Press, New York, NY.

Sekaran, U & Bougie, R 2016, Research methods for business: a skill building approach, 7th edn, John Wiley & Sons, London.

Siraprapasiri, P & Thalang, C 2016, ‘Towards the ASEAN Community: assessing the knowledge, attitudes, and aspirations of Thai university students’, Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 113-147.

Snelson, CL 2016, ‘Qualitative and mixed methods social media research: a review of the literature’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 1-12.

Suharyanti, Y, Masruroh, NA & Bastian, I 2017, ‘A multiple triangulation analysis on the role of product development activities on product success’, International Journal of Engineering Business Management, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 223-226.

Thøgersen, S 2015, ‘I will change things in my own small way: Chinese overseas students, western values, and institutional reform’, Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 103-124.

Tuner, C 2019, ‘Foreign students will be allowed to stay in UK for two years after graduating’, The Telegraph. Web.

Uprichard, E & Dawney, L 2019, ‘Data diffraction: challenging data integration in mixed methods research’, Journal of Mixed Methods Research, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 19-32.

Yuan, J 2018, ‘The culture of science as a new direction for the development of Chinese culture: a review of studies of the culture of science in contemporary China’, Cultures of Science, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 53-67.

Yuval-Davis, N, Wemyss, G & Cassidy, K 2018, ‘Everyday bordering, belonging and the reorientation of British immigration legislation’, Sociology, vol. 52, no. 2, pp. 228-244.

Zhai, K, Gao, X & Wang, G 2019, ‘Factors for Chinese students choosing Australian higher education and motivation for returning: a systematic review’, SAGE Open, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 1-10.

Zhang, Y & Lovrich, N 2016, ‘Portrait of justice: the spirit of Chinese law as depicted in historical and contemporary drama’, Global Media and China, vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 372-389.

Zhou, M 2018, ‘How elite Chinese students view other countries: findings from a survey in three top Beijing universities’, Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, vol. 47, no. 1, pp. 167-188.