Introduction

Exposure to highly stressful major life change events may overwhelm the coping capacity of children, and thus compromise favorable adjustment. Research has indicated that this is particularly true for children in the circumstances surrounding parental divorce, and in the immediate aftermath. Compared to children of intact families, many children of recently divorced families are reported to demonstrate less social competence, more behavioral problems, more psychological distress, and more learning deficits, and are overrepresented in referrals to clinical services (Guidubaldi, Perry, & Cleminshaw, 1984; Kalter, 1977).

Further, an accumulating body of evidence from longitudinal studies of divorce supports continuity of negative effects beyond the 2-year postdivorce crisis period in a substantial minority of children and adolescents (Guidubaldi & Perry, 1984, 1985; Hetherington & Anderson, 1987; Hetherington & Clingempeel, 1992; Hetherington, Cox, & Cox, 1985; Hetherington, Stanley-Hagan, & Anderson, 1989; Wallerstein, 1985, 1987, 1991), as well as the reemergence or emergence of problematic behavior in adolescents who had previously recovered from or adjusted well to parental divorce (Hetherington, 1991a).

Moreover, reports of long-term negative outcomes in offspring beyond the adolescent period suggest that the ramifications of parental divorce on adult behavior may be even more deleterious than those on child behavior (Amato & Keith, 1991b; Zill, Morrison, & Coiro, 1993). The evidence appears to be quite convincing that dissolution of two-parent families, though it may benefit spouses in some respects (Hetherington, 1993), may have farreaching adverse effects for many children.

The divorce and family systems literatures indicate that negative family processes may be more important predictors of poor adjustment in children than family structure (Baumrind, 1991a, 1991b; Kelly, 1988; O’Leary & Emery, 1984). Interparental conflict, for example, is associated with adjustment disturbances in children in both divorced and nondivorced families, and is considered to be a critical mediator of divorce effects in children and adolescents (Atkeson, Forehand, & Rickard, 1982; Emery, 1982; Forehand, Long, & Brody, 1988; Kelly, 1988; Luepnitz, 1979).

In addition, the stress associated with shifting family roles and relationships in newly divorced families contributes to a breakdown in effective parenting practices, which in turn influences adjustment outcomes in children. Decreased levels of warmth, support, tolerance, control, and monitoring, and increased levels of punitive erratic discipline among recently divorced mothers have been related to problematic adjustment in children (Bray, 1990; Brody & Forehand, 1988; Maccoby, Buchanan, Mnookin, & Dornbusch, 1993).

Furthermore, long-term studies of divorce suggest that negative family processes and concomitant stressors may be in operation well after the divorce has occurred, and may become exacerbated when offspring enter adolescence (Hetherington, 1993; Hetherington & Anderson, 1987; Hetherington & Clingempeel, 1992).

Coping with family stressors of such a demanding nature, particularly over an extended time period, may easily tax or exceed the cognitive and behavioral resources that are available to children (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the capacity to cope with and adjust to a stressful life circumstance such as divorce may be even further undermined among those children with difficult temperaments or histories of behavioral or emotional problems (Caspi, Elder, & Herbener, 1990; Hetherington, 1991b; Rutter, 1987).

To test this supposition, the role played by preexisting (i.e., predivorce) individual characteristics such as temperament on children’s responses to divorce needs to be examined, thus advancing a multiple-risk interaction model of adjustment outcomes in children. This same risk model may also be applied to investigate whether divorce affects the course of psychopathology already present in children from a developmental trajectory perspective.

One of the pathways to later disturbance has been linked to earlier temperament difficulties and/or problematic adjustments in childhood, suggesting a vulnerability for future disorders among already troubled children. For example, Mannuzza et al. found that a childhood diagnosis of attention deficit disorder persisted in 40% of probands at age 18, and increased the risk of antisocial and conduct disorder diagnosis by almost five times.

However, while childhood disorder was clearly a risk for later disturbance, the alternative perspective is that stability of diagnosis was not observed in over half the probands. Further, findings from other studies investigating the persistence of childhood hyperactivity and deficits in attention span and impulse control are more equivocal, and indicate more modest relationships in adolescence and in adulthood (see review by Klein & Mannuzza, 1991).

Thomas and Chess (1980) found that the continuity of childhood behavioral adjustment difficulties may be altered by the family’s response to the developing child, and suggested that earlier problems per se are not sufficient to predict later maladjustment. Such observations reflect an interactionalist model of human development whereby individual characteristics interact with psychosocial features of the environment, and as a result are modified (Plomin, 1993; Thomas & Chess, 1980). From a developmental trajectory framework, it is the moderating role played by divorce on the risk of disturbance among already vulnerable children that is at issue. It is this perspective that we consider here.

The purpose of the current study was twofold. The first was to test an adjusted risk model of the effect of family status on outcomes of psychopathology in children by examining whether postdivorce difficulties of children merely reflect stability in preexisting temperament-adjustment difficulties or if divorce has an independent effect. The second was to test a multiple-risk interaction model of temperament-adjustment and family status effects by examining whether parental divorce alters the developmental trajectory already in evidence between preexisting temperament-adjustment difficulties and associated outcomes of psychopathology 8 years later.

There is some evidence that children whose parents eventually divorce exhibit higher levels of problematic behavior prior to divorce than children whose families remain intact (Block, Block, & Gjerde, 1986). The implication is that, in marriages which eventually dissolve, adverse family processes such as parental conflict or disrupted childrearing (most likely due to preoccupation with marital problems) are in evidence before marital dissolution and precipitate predivorce adjustment problems in children.

In order to rule out the possible contaminating effects of divorce-related family processes on children’s adjustment prior to divorce (as demonstrated by Block and colleagues), predivorce differences in child temperament-adjustment between children of families who remained intact versus children of families who divorced were examined.

Only custodial mother families were included in the sample. Because almost one-third of the divorced custodial mothers in this study had remarried, and because the transition into a stepfamily is a major life change with its own complex set of stressors to which children of divorce are often exposed (Bray, 1988; Hetherington, 1987), we examined outcomes as a function of the independent and moderating effects of both single custodial mother family status and stepfamily status.

We considered the outcomes to be long-term in that they were measured 8 years after temperament was observed in 100% of the sample, and 4 or more years postdivorce in 68% of the sample (and 2 or more years postdivorce in 82% of the sample). As time since divorce could not be kept constant for the entire sample, it was included as a control variable in all analyses where family status effects were tested.

The authors proposed to answer the following questions:

- Were there predivorce differences in temperament-adjustment between children who remained in intact families and children whose parents divorced?

- Is problematic temperament-adjustment in childhood a risk for later psychopathology in adolescence?

- Is divorce and/or remarriage a risk for later psychopathology after accounting for the risk of earlier temperament-adjustment problems?

- Does divorce and/or remarriage after the pathway established between preexisting temperament-adjustment characteristics and later outcomes of psychopathology?

- Are there significant sex differences in the effects of temperament-adjustment or divorce and/or remarriage on later psychopathology, or in the effects of the temperament-adjustment to psychopathology trajectory as modified by divorce and/or remarriage?

Method

Sample

The study sample was drawn from the Children in the Community Project, a longitudinal investigation of risk factors for child psychopathology initiated in 1975 in a randomly selected sample of 976 families with children between 1 and 10 years old living in two New York upstate counties. (See Kogan, Smith, & Jenkins, 1977, for a description of sampling procedures and response rates.) The original sample was broadly representative of families living in the northeastern United States. Both mother and child participated in three follow-up studies in 1983, 1986, and 1992. Data from the initial wave in 1975 and first follow-up study conducted 8 years later (in 1983) are employed here.

Of the original 976 families interviewed in 1975, 805 had biological mothers and fathers and were maritally intact. These families comprised the eligible sample for the current study. In 1983 when the children were ages 9 to 18, 699 or 86.8% of the 1975 eligible families were reinterviewed. Youngest children from poor urban families were slightly more likely to be lost; otherwise, demographic characteristics closely matched those of the 1975 eligible sample as tested by chi-square analyses.

Of those reinterviewed, 648 (92.7%) of the 699 families fulfilled study criteria for retention in the current study: 508 families had remained married (intact families), 99 had divorced or separated with single mothers retaining custody of the study children (single custodial mother or SCM families), and 41 had divorced with custodial mothers remarrying (stepfamilies). The remaining 51 families were eliminated because the mothers were no longer living with the children (21), the mothers had been widowed (13), the mothers had obtained more than one divorce (6), the fathers were institutionalized (6), or data were incomplete (5).

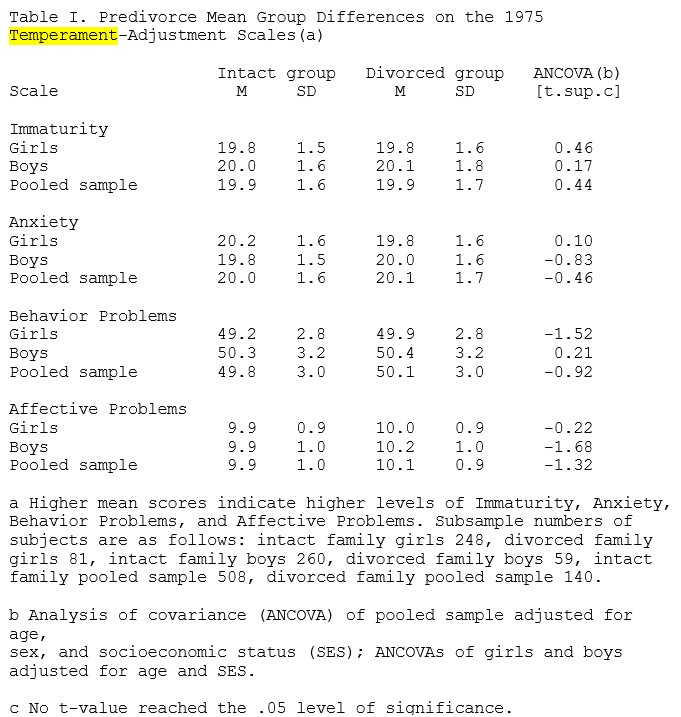

Of the 140 divorced families, 11 separated or divorced within 1 year after the 1975 assessment and 129 (92%) separated or divorced I or more years after the 1975 assessment. Average interval between the 1975 assessment and separation or divorce was 3 1/2 years. Demographic characteristics of the current study sample grouped by family status are presented in Table I.

Materials

The 1975 data set consisted of information obtained from a 1-hour structured interview of mothers covering demographic characteristics, health and pregnancy problems, childrearing practices, and behavioral and emotional functioning of their children. In the 1983 follow-up study, both mothers and children participated. Data obtained from the mothers included portions of the original interview, a self-administered questionnaire on mother and child relationships and personality characteristics, and a child diagnostic interview. Data obtained from youths included parallel personality and diagnostic measures. Youths and their mothers were interviewed separately in their homes by two trained lay interviewers.

Predivorce Measures (1975). The four broad-band measures of children’s temperament-adjustment used here were based on factor analyses of 14 scales reflecting a range of childhood behaviors which captured the temperament constructs originally defined by Thomas, Chess, and Birch (1968). The scales were derived from psychometric analyses of a priori items representing narrow-band symptom sets (Cohen & Brook, 1987).

Sample scale items and Cronbach alphas for the four broad-band measures employed, Immaturity, Anxiety, Behavior Problems, and Affective Problems. Study sample mean scale scores and ranges are 19.9, 16.3 to 25.2 for Immaturity; 20.0, 15.8 to 26.6 for Anxiety; 49.9, 42.1 to 60.6 for Behavior Problems; and 10.0, 8.8 to 14.4 for Affective Problems. High scores on Immaturity indicate a clumsy, distractible child who has much difficulty adapting to a variety of social or learning situations. High scores on Anxiety indicate a sensitive, shy, fearful child. High scores on Behavior Problems indicate an aggressive, argumentative, excitable child with excessive motoric activity. High scores on Affective Problems indicate a child who is frequently unhappy and derives little enjoyment in social situations.

Postdivorce Measures (1983). Diagnoses meeting DSM-III-R criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1987) were derived primarily from mother and child responses to the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-1; Costello, Edelbrock, Dulcan, Kalas, & Klaric, 1984). However, DSM-III-R diagnostic demands were not always met because the DISC-1 was developed to obtain information to satisfy DSM-III criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1980).

Therefore, it was necessary to supplement the information obtained from the DISC-1 with information from items elsewhere in the protocol in order to adequately assess DSM-III-R symptoms. Syndrome scales of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Separation Anxiety Disorder, and Major Depressive Disorder, each based on all relevant items, were constructed. We considered diagnostic criterion to be met with affirmation of the presence of a symptom by either mother or child. For the current study, children who met diagnostic criteria and also had scaled scores of more than 1 standard deviation above the population mean were give a diagnosis.

Support for the reliability, criterion validity, and construct validity of these diagnoses was reflected in improved agreement with clinically obtained diagnoses when scaled measures were used (Cohen, O’Connor, Lewis, & Malachowski, 1987; Cohen, Velez, et al., 1987). The diagnoses also have been related in theoretically meaningful ways to risk factors measured prospectively (Velez, Johnson, & Cohen, 1989), to pregnancy and early health problems (Cohen, Velez, Brook, & Smith, 1989), and to treatment (Cohen, Kasen, Brook, & Streuning, 1991). Mothers provided reports of divorce or remarriage since their previous interviews.

Data Analytic Procedure

The first step was to examine whether any negative influences of divorce-related processes were indeed in operation prior to actual physical separation of spouses (as suggested by Block et al., 1986). Predivorce temperament-adjustment differences between children of families who remained intact and children whose parents later divorced (including mothers who had remarried or remained single) were tested by analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs). Analyses were conducted separately for girls and boys (controlled for age and SES), and for the pooled sample (with sex added to the control variables).

For the longitudinal analyses, we began by using set correlation procedure to examine the overall main and interaction effects of 1975 temperament-adjustment and family status on the set of six 1983 psychiatric diagnoses as a safeguard against Type 1 error (Cohen & Cohen, 1983). In set correlation, multiple independent and dependent variables can be tested simultaneously, and the effects of control variables can be partialed out of both the independent and dependent variable sets.

Thus, because a smaller number of significance tests are conducted, and because the effects of control variables are eliminated, the likelihood of obtaining significant results by chance is reduced. When, in set correlation, a significant main or interaction effect on the set of six 1983 psychiatric diagnoses was observed, each diagnostic outcome was regressed against the specific risk(s) and all control variables to obtain the odds ratio (i.e., the degree of increased risk for a given disorder). Logistic regression is the procedure of choice for analyzing the effects of continuous or categorical risk variables on a binary outcome variable in terms of the odds of being in one of two categories versus the other (Fleiss, Williams, & Dubro, 1986).

There is substantial empirical evidence available to support a differential effect of divorce for boys and for girls (see reviews by Zaslow, 1988, 1989). However, although a sex-specific analysis of divorce effects may be considered more informative than an analysis which employs sex as a control variable, it also precludes testing for significant sex differences. Moreover, to do both becomes quite unwieldy with such a large set of variables. Therefore, all longitudinal analyses addressing main and interaction effects of temperament-adjustment and family status on outcomes were tested for sex differences, and where significant, separate results for girls and boys are reported.

Following the cross-sectional analysis of predivorce differences, the longitudinal analyses of main and interaction effects of temperament-adjustment and family status proceeded as follows:

- Main Effects of Temperament-Adjustment. The set of six 1983 psychiatric diagnoses was regressed against each 1975 temperament-adjustment scale after partialing out the main effects of age, sex, and SES. The temperament-adjustment scales were standardized for all regression analyses so that the unit change in the dependent variable set would be comparable across all six diagnoses.

- Main Effects of Family Status. The set of six 1983 psychiatric diagnoses was regressed against family status after partialing out the main effects of age, sex, SES, time since divorce, and all four 1975 temperament-adjustment scales. Family status was entered into all equations as two dummy variables: single custodial mother families versus intact families and stepfamilies, and stepfamilies versus intact families and SCM families. When considered simultaneously, the regression coefficients reflect the differences between SCM families and stepfamilies, respectively, with intact families (Cohen & Cohen, 1983, p. 194).

- Interaction Effects Between Temperament-Adjustment and Family Status. The set of six 1983 psychiatric diagnoses was regressed against the interaction between each 1975 temperament-adjustment scale and family status after partialing out the main effects of age, sex, SES, time since divorce, family status, and all four 1975 temperament-adjustment scales.

- Sex Differences. Potential sex differences in main and interaction effects of temperament-adjustment and family status, and subsequent pairwise comparisons of effects for each sex, were examined.

Results

Predivorce Differences

If predivorce processes were in operation, we would expect the 1975 temperament-adjustment scales to differentiate between children of families who remained intact and children of families who divorced by 1983. However, there were no significant predivorce differences in Immaturity, Anxiety, Behavior Problems, or Affective Problems between girls of intact families and girls of divorced families, or between boys of intact families and boys of divorced families. We repeated these analyses for the pooled sample to increase power, but still found no predivorce differences.

A Developmental Trajectory for Vulnerability

Significant main effects of predivorce temperament-adjustment on 1983 psychiatric diagnoses were observed with set correlation for Immaturity, F(6, 638) = 2.72, p [less than].05, Behavior Problems, F(6, 638) = 8.85, p [less than].001, and Affective Problems, F(6, 638) = 2.50, p [less than!.05, and followed up with logistic regression. No overall effect was observed for Anxiety, F(6, 638) = 0.35, p [greater than].05. Youths who scored high on Immaturity were at significant increased risk for ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder.

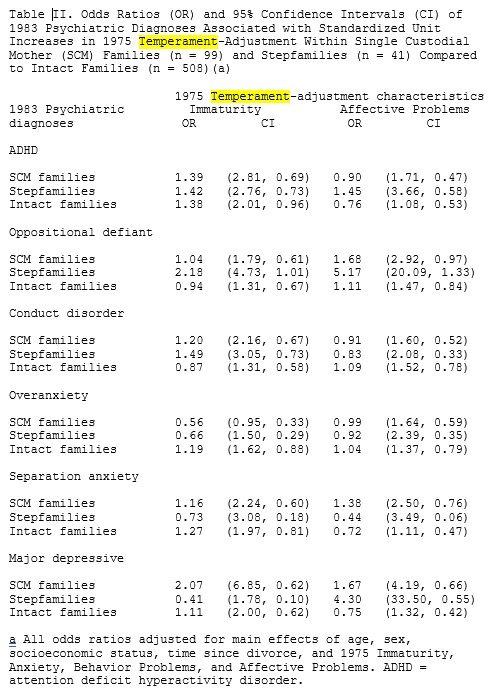

Youths who scored high on Behavior Problems were at significant increased risk for ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, overanxiety disorder, and major depressive disorder. And youths who scored high on Affective Problems were at significant increased risk for oppositional defiant disorder. There was a near significant trend (p [less than].10) for youths who scored high on Immaturity to be at increased risk for major depressive disorder, and for youths who scored high on Behavior Problems to be at increased risk for separation anxiety disorder. See Table II for odds ratios and confidence intervals. (An odds ratio of 3.0 is interpreted as being three times more at risk for disorder, whereas an odds ratio at a fractional level, e.g., 1.5, is interpreted as being at 50% increased risk for disorder.)

A significant two-way interaction effect between sex and Behavior Problems on 1983 psychiatric diagnoses was observed with set correlation, F(6, 637) = 2.46, p [less than].05, and followed up with logistic regression. Compared to boys who scored high on Behavior Problems, girls with comparable scores were at significant increased risk for ADHD and separation anxiety disorder, and showed a near significant trend to be at increased risk for oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder.

Examination of sex-specific odds ratios revealed a similar predictive pattern of high scores on 1975 Behavior Problems and later disorder across sex; however, the data suggest a somewhat stronger effect for girls than for boys overall.

Main Effects of Family Status on Adolescent Psychopathology

Significant independent main effects of family status on 1983 psychiatric diagnoses were observed with set correlation, F(12, 648) = 3.31, p [less than!.001, and followed up with logistic regression. Youths in single custodial mother families were three times more at risk for conduct disorder, almost two times more at risk for overanxiety disorder, and almost three times more at risk for separation anxiety disorder than youths in intact families. In addition, there was a near significant trend for youths in SCM families to be almost two times more at risk for oppositional defiant disorder than youths in intact families. Youths in stepfamilies were over four times more at risk for ADHD and almost four times more at risk for conduct disorder than youths in intact families.

A significant two-way interaction effect between sex and family status on 1983 psychiatric diagnoses was observed with set correlation, F(6, 637) = 2.46, p [less than].05, and followed up with logistic regression. The risk of major depressive disorder was significantly higher in SCM family boys than in SCM family girls. Inspection of sex-specific odds ratios revealed that boys in SCM families were over five times more at risk for major depressive disorder than were boys in intact families. Girls in SCM families, on the other hand, were no more at risk for major depressive disorder than were girls in intact families. In general, there were more pervasive effects of SCM family status for boys than for girls (albeit only significantly more so for major depressive disorder).

Compared to boys in intact families, boys in SCM families were at significant increased risk for four of the six diagnoses (conduct disorder, overanxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder). In contrast, SCM family status effects on girls were more modest, and did not reach significance (compared to intact family girls) when treated independently of the effects for boys, despite the larger ratio of girls to boys in that family context and subsequent increase in power. There was no significant difference in risk of psychiatric disorder between girls and boys in stepfamilies.

The observed variations in pattern of outcome and family status when girls and boys were treated independently are worthy of note. Compared to intact family girls, SCM family girls were not at significant increased risk for any of the six disorders, whereas stepfamily girls were at a significant increased risk for ADHD, and at a near significant increased risk for major depressive disorder and overanxiety disorder.

Compared to intact family boys, SCM family boys were at a significant increased risk of conduct disorder and all three internalizing disorders, whereas stepfamily boys were at a significant increased risk of disruptive disorders (ADHD, conduct disorder) only. Thus, in these reduced, independently treated samples, girls were at significantly elevated risk for psychiatric disturbance only in stepfamilies, whereas boys were at significantly elevated risk for psychiatric disturbance within both the SCM family and stepfamily contexts, but the expression of risk varied.

Interaction Effects of 1975 Temperament-Adjustment and Family Status on Adolescent Psychopathology

Significant two-way interaction effects between Immaturity and family status, F(12, 1,260) = 2.54, p [less than].01, between Behavior Problems and family status, F(12, 1,260) = 1.80, p [less than].05, and between Affective Problems and family status, F(12, 1,260) = 3.03, p [less than!.001, on 1983 psychiatric diagnoses were observed with set correlation and followed up with logistic regression. A near significant trend for Anxiety and family status to interact was also observed, F(12, 1,260) = 1.65, p [less than!.10.

Among youths who scored high on Immaturity, those in stepfamilies were over two times more at risk for oppositional defiant disorder than those in intact families; however, those in single custodial mother families were at only about half the risk for overanxiety disorder compared to those in intact families. Among youths who scored high on Affective Problems, those in stepfamilies were over five times more at risk for oppositional defiant disorder than those in intact families.

There was also a near significant trend for SCM family youths who scored high on Affective Problems to be more at risk for oppositional defiant disorder than were intact family youths with comparable scores. Interaction effects between Behavior Problems and family status were not observed with logistic regression: Increased risk of later disorder given high scores on Behavior Problems was observed for all family status groups.

A significant three-way interaction effect between sex, Immaturity, and family status on 1983 psychiatric diagnoses was observed with set correlation, F(12, 1,250) = 2.44, p [less than].01, and followed up with logistic regression. The risk of conduct disorder was significantly higher in stepfamily boys who scored high on Immaturity than in stepfamily girls who scored high on Immaturity.

Stepfamily boys with high Immaturity scores were over six times more at risk for conduct disorder than were intact family boys with comparable Immaturity scores. Stepfamily girls with high Immaturity scores, on the other hand, were no more at risk for conduct disorder than were intact family girls with comparable Immaturity scores.

In addition, SCM family boys who scored high on Immaturity were at a near significant increased risk for separation anxiety disorder compared to SCM family girls who scored high on Immaturity. The risk of separation anxiety disorder increased almost three times among SCM family boys with high Immaturity scores compared to intact family boys with comparable Immaturity scores. SCM family girls with high Immaturity scores, however, were no more at risk for separation anxiety disorder than were intact family girls with comparable Immaturity scores.

Discussion

Our intention here was to test risk associated with problematic predivorce temperament-adjustment and nonintact family status for later disturbance as interpreted from a developmental trajectory framework. Data are longitudinal and were obtained prospectively from a randomly selected community sample prior to and independently of divorce. Outcomes were measured 8 years after temperament-adjustment was observed, and 4 or more years postdivorce for 68% of the sample, and 2 or more years postdivorce for 82% of the sample.

Mother reports were used for the predivorce temperament-adjustment characteristics and combined mother and child reports were used for the diagnostic outcomes so that no informant was the sole provider of both the independent and dependent variables. To the best of our knowledge, this is the only large-scale study that demonstrates divorce effects in an epidemiological sample after controlling for predivorce temperament-adjustment characteristics. Thus, findings obtained here take on added import for the study of children’s response to marital dissolution.

Before we consider the implications of these results, some methodological issues should be addressed. First, because ethnic and cultural norms involving divorce, child custody, and remarriage vary (Cherlin, 1992), generalizability of findings from a primarily white Catholic sample may be limited. Second, although combined mother-child reports were used for the 1983 psychiatric diagnoses, only mothers provided information about predivorce temperament-adjustment. It is reasonable to assume that reports by single informants are more subject to individual biases than are the reports of multiple informants (Hetherington & Clingempeel, 1992).

However, as these biases would affect children of both intact and divorced families similarly (suggested here by the lack of significant predivorce temperament-adjustment differences between these two groups), this weakness is less problematic in the current study. Furthermore, the strong association between temperament-adjustment and later disturbance found here (the latter derived from combined mother and youth reports) offers some validation of mother reports of earlier behaviors.

Finally, although not a methodological issue, we are well aware that children’s responses to divorce may be less contingent upon family status than upon certain aspects of the home environment, namely, a close, trusting, and mutually respectful relationship between a child and his or her parents, and parental establishment and enforcement of standards of behavior (Maccoby et al., 1993).

Family status, on the other hand, is more structural in nature, and cannot capture the complexity of postdivorce family reorganizations and changes in roles and relationships. However, permanent disruption of intact family status does imply a number of substantial stressors and life changes that require adaptive responses and coping skills on the part of children, no matter how smoothly postdivorce processes may be operating.

Thus, in this study, where the focus is on predivorce vulnerability and subsequent outcomes 8 years later, we have used family status as an abbreviated proxy for the demands placed by divorce and consequent family restructuring on children’s adaptive resources and coping strategies. Nonetheless, this does not obviate the need to study postdivorce family processes in children whose adaptive and coping capabilities may be impaired.

Predivorce Temperament-Adjustment

Predivorce temperament-adjustment did not differentiate girls or boys whose parents divorced from girls or boys whose families remained intact, despite the unusually large sample and substantial statistical power. These findings are in contrast to those of Block et al. (1986), who did find preexisting differences, particularly among boys, and attributed them to divorce processes in effect prior to the actual event. Comparable to Block et al.’s study, we examined divorce as occurring in an 8-year period and on average had a 3 1/2-year interval between predivorce assessment and marital dissolution.

However, the differing methodologies employed may help to explain why findings of predivorce differences were not replicated here. We used a random community sample of families with 1 to 10-year-old children and interviewed mothers, whereas Block and colleagues used a university preschool sample of children and their parents (most of whom were middle and upper class) and administered a Q-sort task to teachers. Thus, sample selection criteria, instrumentation, and informants were not at all comparable across studies.

In addition, in the Block et al. study, the principal findings were based on a relatively small sample of thirty-two 7-year-old boys, five of whom came from families who subsequently divorced and 27 of whom came from families who remained intact over the 8 years from the age 6 to 7 to the age 14 to 15 assessments. Moreover, predivorce differences between the five divorced family boys and 27 intact family boys reaching conventional significance levels (i.e., p [less than].05) at the 7-year-old assessment included nine of the 63 Q-sort items.

Although these differences may, to some degree, account for the inconsistent outcomes, this discrepancy between two major studies underscores the need for future investigations to gather prospective longitudinal data in order to reconcile the confounding of predivorce processes with divorce effects.

Temperament-Adjustment Effects on Later Disturbance

A strong developmental trajectory of vulnerability was supported here after adjusting for age, sex, and SES. Children who had problematic temperament-adjustment 8 years earlier, specifically those who were socially immature or who had disruptive or affective problems, were at increased risk for later psychiatric disturbance. Prediction of later disturbance by temperament-adjustment supported the developmental trajectory posited.

This finding, coupled with that of no predivorce temperament-adjustment differences between children of families who divorced and children whose families remained intact, allowed us to use temperament-adjustment as a salient but nonconfounded control for examining effects of divorce independent of prior problematic adjustment.

Single Custodial Mother Family Status Effects

In comparison with youths in intact families, youths living in single custodial mother families were at increased risk for both disruptive disorders (conduct and oppositional defiant) and anxiety disorders (overanxiety and separation anxiety). These findings are in accord with those of studies of long-term divorce effects reporting both externalizing and internalizing problem behavior in adolescent offspring residing with divorced nonmarried mothers (Hetherington & Clingempeel, 1992; Wallerstein, 1985).

Externalizing symptoms in boys within this family context have been attributed to loss of the fathers in their role as a socializing agent and model for identification (Emery, 1988). Contact with nonresidential fathers tends to wane following the postdivorce transitional period (Furstenberg, Peterson, Nord, & Zill, 1983), and, when in effect, may be less characteristic of a parenting relationship than of a more peer-like friendship one (Emery, 1988). This latter phenomenon may explain the inconsistent findings regarding the relationship between continued contact with nonresident fathers and adjustment outcomes in children.

While some studies of divorce have reported positive effects of regular and frequent contact with nonresident fathers on offspring adjustment (Guidubaldi, Cleminshaw, Perry, & McLaughlin, 1983; Lewis & Wallerstein, 1987), others have failed to find benefits to be derived from continued involvement (Clingempeel & Segal, 1986; Furstenberg, Morgan, & Allison, 1987; Kurdek, Blisk, & Siesky, 1981; Luepnitz, 1986).

Discrepant findings regarding the impact of nonresident father contact may also be due in part to the risk of loyalty conflicts in adolescent children who attempt to maintain close ties to two warring parents (Buchanan, Maccoby, & Dornbusch, 1991). Accordingly, there is also evidence that regular and frequent contact between nonresident fathers and mother-resident offspring may be an artifact of low levels of interparental contact (Hetherington, Cox, & Cox, 1978, 1982).

Nonetheless, whichever of these factors bears the brunt of responsibility for discordant outcomes, a consequence of the limited and altered exposure to biological fathers formerly in residence may be a decline in paternal monitoring and control. Coupled with the maternal decline in monitoring and control following divorce, this may provoke a disruptive response from sons that could persist over time. Given the escalating coercive negativity reported in divorced nonremarried mother-adolescent son relationships (Hetherington & Clingempeel, 1992), it is also possible that after a hiatus of decreasing problematic behavior, boys revert to an exaggerated masculine response in adolescence by engaging in machismo-like behavior as a means of separating from their mothers and establishing their own identities.

Girls, on the other hand, who typically experience close, harmonious relationships with their unremarried mothers after an initial adjustment period (e.g., Hetherington et al., 1979, 1985), become argumentative and openly hostile in adolescence (e.g., Hetherington, 1991a; Kalter, Riemer, Brickman, & Chen, 1985; Newcomer & Udry, 1987). This has been attributed in part to the increasing sexual tensions and heterosexual activities that are typical of the adolescent period. Further, conflicted mother-daughter relationships may be exacerbated by the increased monitoring of daughters’ activities in adolescence by divorced nonremarried mothers (Hetherington & Clingempeel, 1992).

In contrast to a disruptive response in children of divorce, reports of symptoms of anxiety and depression have been much more equivocal. This has been attributed in part to less reliable assessment of internalizing disorders (Achenbach, McConaughy, & Howell, 1987), and to minimal awareness on the part of divorced mothers of their offsprings’ feelings (Wallerstein & Kelly, 1980). The latter may hold true even more so in adolescence.

Findings of internalizing disorder here may be due in part to the use of instruments with empirically supported reliability and validity, and to the use of diagnostic criteria equally dependent on self and mother informants. It is also possible that ongoing stressors experienced by some nonremarried mothers, e.g., task overload, household disorganization, child-rearing problems, loneliness, and depression (Hetherington & Clingempeel, 1992), may contribute to the stressors encountered by children in the developmental transitions to adolescence.

Although single custodial mother effects for boys appeared to be more pervasive, sex differences were not significant with the exception of effects on depression. When treated independently of girls, boys living with their nonremarried mothers were over five times more at risk for major depressive disorder than were intact family boys. Others have suggested that boys respond more adversely than girls to psychosocial stressors, and particularly to residing with nonremarried mothers (Rutter, 1970; Zaslow & Hayes, 1986).

However, heretofore most reports have indicated that they do so in an undercontrolled hostile manner (Emery, 1982, 1988; Emery, Hetherington, & DiLalla, 1985). From a psychoanalytic perspective and the conceptual work of John Bowlby on attachment, separation, and loss (Bowlby, 1973, 1980), parental loss via divorce or other circumstances for that matter is also a formidable risk factor for depression.

For boys, father absence through divorce may not only mean loss of a male model and authority figure, but the more painful psychological loss of a primary attachment figure. It also may be that depression among boys within this family context is more likely with the passage of time, particularly as the child reaches the early and middle adolescent years and has the cognitive capacity to better understand the finality of the divorce (Kurdek et al., 1981). This perception may very well be reinforced by the diminished utilization of visitation rights by nonresidential fathers once the immediate crisis period following divorce has passed (Furstenberg et al., 1983).

Empirical support of internalizing symptoms has been reported in long-term studies of divorce effects (Hetherington et al., 1985; Wallerstein, 1985, 1987), and in the 5-year follow-up of the National Survey of Children (e.g., Peterson & Zill, 1986), after a number of years had elapsed since the divorce and most children were in their preadolescent to adolescent years. However, observation of a significantly greater depressive response in adolescent boys than in adolescent girls to long-term residence in a nonremarried mother household has not previously been reported.

Stepfamily Status Effects

In comparison with youths in intact families, youths living in stepfamilies were at increased risk for ADHD and conduct disorder. Persistent reports of school problems among children of divorce due more to disruptions in concentration and behavioral problems than to deficits in learning ability (e.g., Guidubaldi et al., 1984; Hetherington, Camara, & Featherman, 1983), may be a repercussion of one or both of these syndromes for some children living in stepfamilies. The findings here lend support to reports that children in stepfamilies are more at risk for developing behavioral problems, psychological stress, and lower social competency than are comparably aged children in intact families (Anderson & White, 1986; Bray, 1988; Hetherington, 1987; Hetherington & Clingempeel, 1992).

Data reported by Bray and Berger (1993) suggest that children who experience a remarriage are at elevated risk for developing psychological problems and adjustment difficulties during the transitional phase of stepfamily formation and after 5 years in a stepfamily, especially as they enter adolescence. Furthermore, Hetherington and Clingempeel (1992) reported that after 2 years of remarriage, thus implying a period of restabilization, adolescent step-children were still demonstrating more behavioral problems and psychological distress than were same age peers in intact families.

Other findings suggest that stepfamilies are at greater risk than intact families for developing conflictual parent-child relationships (Hetherington, 1987; Santrock, Warshak, Lindberg, & Meadows, 1982), and that these relationships are related to developmental problems during adolescence (Bray & Berger, 1993; Garbarino, Sebes, & Schellenbach, 1984; Hetherington & Clingempeel, 1992).

No significant sex interaction was observed here within the stepfamily context. Although significant sex differences have been observed with younger children residing in stepfamilies (Clingempeel, Brand, & Ievoli, 1984; Hetherington et al., 1979, 1982, 1985), few differences have been reported in adolescence (Bray & Berger, 1993; Hetherington & Clingempeel, 1992).

When treated independently, stepfamily girls in our sample were at elevated risk for ADHD, overanxiety disorder, and major depressive disorder, whereas stepfamily boys were at elevated risk for the disruptive disorders only (ADHD and conduct disorder). Living in a stepfather family may be particularly stressful for adolescent girls, where the potential for sexual tension (Hetherington, 1991a; Newcomer & Udry, 1987) and interrupted closeness with the mother (Kalter, 1977; Kalter et al., 1985) may foster internalizing as well as externalizing symptoms.

Temperament-Adjustment/Family Status Interaction Effects

There was some support for the alteration of a pathway to disorder, i.e., the trajectory toward future disturbance initiated by problematic temperament-adjustment characteristics was altered by the impact of divorce. Living in a stepfamily significantly increased the likelihood of oppositional defiant disorder given earlier social immaturity or affective problems. Being a part of a stepfamily requires accommodating to a second set of postdivorce transitions, sometimes before those of the single-parent family have been resolved (Hetherington & Clingempeel, 1992). The child merging into a stepfamily is asked to adapt to a new family member in a position of parental authority, and oftentimes to a new home, school, and peers.

Children who have a history of social immaturity or affective problems may be less able to adapt to new situations and thus more vulnerable to disorder when such stressors are present. The significant three-way interaction between sex, Immaturity, and stepfamily status suggests that socially immature stepfamily boys respond with an increased risk of conduct disorder as well. Custodial mothers and their new spouses, attempting to solidify their relationship, may not be able to meet the increased demands for attention or give the extra support necessary to bolster the vulnerable child, who in turn may respond by acting out in a defiant manner.

We also found an increased risk for oppositional defiant disorder to occur, although to a lesser extent, in children with earlier affective problems residing with their single custodial mothers. While not having to negotiate the changes characteristic of stepfamily adaptation, these children must still adapt to a stressful situation where the old rules do not apply, thus overwhelming their already vulnerable coping capacities.

On the other hand, we also found that among youths who had high predivorce social immaturity, those in single custodial mother families were at decreased risk for overanxiety disorder compared to those in intact families; this occurred with boys and, to a lesser extent, with girls, DSM-III-R diagnostic criteria for overanxiety disorder include excessive worry over past and future behaviors, excessive concern over competence, and marked self-consciousness.

Children living with single custodial mothers are often asked to play more responsible roles in family matters, e.g., caring for younger siblings, having an equal say in major family decisions, and/or acting as confidantes and peers to their newly divorced mothers (Glenwick & Mowerey, 1986; Hetherington et al., 1983; Reinhard, 1977; Weiss, 1979), so that the mother-child relationship becomes more of a mutually dependent one rather than a hierarchical nurturer-dependent one.

It is possible that these more “adult” experiences have enhanced immature children’s social skills and self-esteem, making it less likely that they become overanxious compared to immature children growing up in intact families who may not be afforded similar opportunities to develop earlier maturity. It also may be that mothers would be more likely to turn to their sons than their daughters to fill the role formerly held by their spouses, particularly in decision making, thus explaining the stronger effects found here for boys.

An alternative explanation for this effect in boys is that mothers, in general, are less demanding of maturity in their adolescent male offspring than are fathers, and therefore socially immature boys are less anxious when they are not being pushed to act more maturely by fathers (Baumrind, 1991a, 1991b).

Conclusions and Implications

In sum, although previous reports of predivorce behavioral differences in children were not confirmed, we found the expected effects of early temperamental risk and of family disruption on the development of disorders assessed eight years later. Furthermore, effects of divorce on increased risk of psychiatric disorder were independent of prior problematic temperament-adjustment. Effects of single custodial mother family status tended to be larger for boys, not only for disruptive disorders as shown previously but also for affective and anxiety disorders, and negative effects of living in a stepfamily were more likely to be expressed with internalizing disorders for girls and with externalizing disorders for boys.

Thus, sons may experience a more formidable psychological loss when fathers leave than do daughters, whereas daughters experience internalizing symptoms with the addition of a stepfather. Perhaps the presence of a stepfather is tantamount to the psychological loss of the mother for daughters in terms of divided time, attention, and loyalty. The potential for sexual tension in the adolescent stepdaughter-stepfather relationship may also be a factor.

Increased risk of conduct disorder was observed in both single custodial mother family boys and stepfamily boys. The risks associated with earlier vulnerable temperament were increased by divorce and remarriage, especially with regard to subsequent oppositional defiant disorder, and for boys, conduct disorder as well. On the other hand, living in a single custodial mother family was also associated with a decline in the trajectory toward overanxiety disorders in those with an earlier vulnerable temperament, thus reflecting the complicated process of temperament-environment interactions.

In terms of future research, there are several useful directions to take. First, stress models hypothesize that protective factors may buffer the negative effect of stressful events. Thus, when the family structure is examined within the context of the larger family system, there may be alternative explanations for outcomes. For instance, it is conceivable that having a supportive sibling or a supportive substitute parental figure (such as a grandparent) could buffer the negative effects of living in single custodial mother family or stepfamily situations. Second, we have alluded to some of the potential mediating mechanisms between family structure and adolescent outcomes.

Future research would benefit from focusing attention on other possible mechanisms. For example, the impact of family structure on some adolescent outcomes may be mediated by the peer group. A case in point is conduct disorders. Children residing with divorced nonremarried mothers experience less parental control and monitoring, and so may be more likely to associate with deviant peers which in turn increases the risk for conduct disorders.

Finally, further research should study the manner in which children and adolescents use coping strategies to alter the likelihood of adverse emotional and behavioral outcomes when living in single custodial mother families and stepfamilies. We are mindful that family status is a structural variable, and certainly not homogeneous with regard to the complex economic, social, and psychological processes occurring within family structures. However, further investigation of the negotiation of formidable psychosocial stressors as a function of individual traits and characteristics in children will clarify the role of divorce processes on children’s well-being.

The findings of long-term divorce effects on children’s well-being have implications for intervention. Given the independent effects of living in a single custodial mother family or a stepfamily on DSM-III-R disorders, preadolescent and adolescent children of divorce may benefit from support and guidance at a professional level so that they may cope more efficiently with the typical stressors characteristic of this developmental stage.

Given the increased risk of disorder among already troubled children, this may be especially critical for those with previous problematic adjustment. Adolescents have limited independent access to mental health services (Cohen & Hesselbart, 1993); however, utilization of clinical services within the school system is an accessible resource for adolescents.

Alerting school guidance counselors and psychologists, particularly at the secondary school level, would facilitate obtaining such services. In addition, educating parents within these family contexts to recognize when a syndrome of symptoms connotes disturbance at a clinical level may provide the impetus necessary to motivate them to seek out this help for their children in a wider variety of clinical settings in the community.

References

Achenbach, T. M., McConaughy, S. H., & Howell, C. T. (1987). Child/adolescent emotional problems: Implications of cross-informant informants for situational-specificity. Psychological Bulletin, 101, 213-232.

Amato, P. R., & Keith, B. (1991a). Parental divorce and the well-being of children: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 110, 26-46.

Amato, P. R., & Keith, B. (1991b). Parental divorce and adult well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53, 43-58.

American Psychiatric Association (1980). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

American Psychiatric Association (1987). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed., rev.). Washington, DC: Author.

Anderson, J. Z., & White, G. D. (1986). Dysfunctional intact families and stepfamilies. Family Process, 25, 407-422.

Atkeson, B. M., Forehand, R., & Rickard, K. M. (1982). The effects of divorce on children. In B. B. Lahey & A. E. Kazdin (Eds.), Advances in clinical child psychology (Vol. 5, pp. 255-281). New York: Plenum Press.

Baumrind, D. (1991a). Effective parenting during the early adolescent transition. In P. A. Cowan & E. M. Hetherington (Eds.), Family transitions (pp. 111-164). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Baumrind, D. (1991b). The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance abuse. Journal of Early Adolescence, 11, 56-94.

Block, J. H., Block, J., & Gjerde, P. F. (1986). The personality of children prior to divorce: A prospective study. Child Development, 57, 827-840.

Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss (vol. 2): Separation. New York: Basic.

Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and loss (vol. 3): Loss, sadness, and depression. New York: Basic.

Bray, J. H. (1988). Children’s development in early remarriage. In E. M. Hetherington & J. D. Arasteh (Eds.), The impact of divorce, single parenting and stepparenting on children (pp. 279-298). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Bray, J. H. (1990). Impact of divorce on the family. In R. E. Rakel (Ed.), Textbook of family practice (4th ed., pp. 111-122). Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders.

Bray, J. H., & Berger, S. H. (1993). Developmental issues in stepfamilies research project: Family relationships and parent-child interactions. Journal of Family Psychology, 7, 76-90.

Brody, G., & Forehand, R. (1988). Multiple determinants of parenting: Research findings and implications for the divorce process. In E. M.

Hetherington & J. Arasteh (Eds.), Impact of divorce, single parenting and stepparenting on children (pp. 117-134). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Buchanan, C. M., Maccoby, E. E., & Dornbusch, S. M. (1991). Caught between parents: Adolescents’ experience in divorced homes. Child Development, 62, 1008-1029.

Camara, K. A., & Resnick, G. (1988). Interparental conflict and cooperation: Factors moderating children’s post-divorce adjustment. In E. M.

Hetherington & J. Arasteh (Eds.), Impact of divorce, single parenting and stepparenting on children (pp. 169-196). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Caspi, A., Elder, Jr., G. H., & Herbener, E. S. (1990). Childhood personality and the prediction of life-course patterns. In L. Robins & M.

Rutter (Eds.), Straight and devious pathways from childhood to adulthood (pp. 13-35). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Cherlin, A. J. (1992). Marriage, divorce, and remarriage. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Clingempeel, W. G., Brand, E., & Ievoli, R. (1984). Stepparent-stepchild relationships in stepmother and stepfather families: A multimethod study. Family Relations, 33, 465-473.

Clingempeel, W. G., & Segal, S. (1986). Stepparent-stepchild relationships and the psychological adjustments of children in stepmother and stepfather families. Child Development, 57, 574-584.

Cohen, J., & Cohen, P. (1983). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Cohen, P., & Brook, J. S. (1987). Family factors related to the persistence of psychopathology in childhood and adolescence. Psychiatry, 50, 332-344.

Cohen, P., Cohen, J., Kasen, S., Velez, C. N., Hartmark, C., Johnson, J., Rojas, M., Brook, J., & Struening, E. L. (1993). An epidemiological study of disorders in late childhood and adolescence – I. Age- and gender-specific prevalence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 34, 851-867.

Cohen, P., & Hesselbart, C. S. (1993). Demographic factors in the use of children’s mental health services. American Journal of Public Health, 83, 49-52.

Cohen, P., Kasen, S., Brook, J. S., & Struening, E. L. (1991). Diagnostic predictors of treatment patterns in a cohort of adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 30, 989-993.

Cohen, P., O’Connor, P., Lewis, S. A., & Malachowski, B. (1987). A comparison of the agreement between the DISC and K-SADS-P interviews of an epidemiological sample of children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 26, 662-667.

Cohen, P., Velez, C. N., Brook, J. S., & Smith, J. (1989). Mechanisms of the relationship between perinatal problems, early childhood illness, and psychopathology in late childhood and adolescence. Child Development, 60, 701-709.

Cohen, P., Velez, C. N., Kohn, M., Schwab-Stone, M., & Johnson, J. (1987). Child psychiatric diagnosis by computer algorithm: Theoretical issues and empirical tests. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 26, 631-638.

Costello, A. J., Edelbrock, C. S., Dulcan, M. K., Kalas, R., & Klaric, S. H. (1984). Testing of the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC) in a clinical population (Final report to the Center for Epidemiologic Studies, National Institute for Mental Health). Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh.

Emery, R. E. (1982). Interparental conflict and the children of discord and divorce. Psychological Bulletin, 92, 310-330.

Emery, R. E. (1988). Marriage, divorce, and children’s adjustment. Developmental clinical psychology and psychiatry: Vol. 14. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Emery, R. E., Hetherington, E. M., & DiLalla, L. F. (1985). Divorce, children, and social policy. In H. Stevenson & A. Siegal (Eds.), Child development research and social policy (pp. 189-266). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Farrington, D., Loeber, R., & Van Kammen, W. B. (1990). Long-term criminal outcomes of hyperactivity-impulsivity-attention deficit and conduct problems in childhood. In L. Robins & M. Rutter (Eds.), Straight and devious pathways from childhood to adulthood (pp. 62-81). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Fleiss, J. L., Williams, J. B., & Dubro, A. F. (1986). The logistic regression analysis of psychiatric data. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 20, 145-209.

Forehand, R., Long, N., & Brody, G. (1988). Divorce and marital conflict: Relationship to adolescent competence and adjustment in early adolescence. In E. M. Hetherington & J. Arasteh (Eds.), Impact of divorce, single parenting and stepparenting on children (pp. 155-167). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Furstenberg, F. F., Jr., Morgan, S. P., & Allison, P. D. (1987). Paternal participation and children’s well-being after marital dissolution. American Sociological Review, 52, 695-701.

Furstenberg, F. F., Jr., Peterson, J. L., Nord, C. W., & Zill, N. (1983). The life course of children of divorce: Marital disruption and parental contact. American Sociological Review, 48, 656-668.

Garbarino, J., Sebes, J., & Schellenbach, C. (1984). Families at risk for destructive parent-child relations in adolescence. Child Development, 55, 174-183.

Garmezy, N., Masten, A. S., & Tellegen, A. (1984). The study of stress and competence in children: A building block for developmental psychopathology. Child Development, 55, 97-111.

Gersten, J. C., Langner, T. S., Eisenberg, J. G., & Simcha-Fagan, O. (1977). An evaluation of the etiological role of stressful life change events in psychological disorders. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 18, 228-244.

Glenwick, D. S., & Mowerey, J. D. (1986). When parent becomes peer: Loss of intergenerational boundaries in single parent families. Family Relations, 35, 57-62.

Guidubaldi, J., Cleminshaw, H. K., Perry, J. D., & McLaughlin, C. S. (1983). The impact of parental divorce on children: Report of the nationwide NASP study. School Psychology Review, 12, 300-323.

Guidubaldi, J., & Perry, J. D. (1984). Divorce, socioeconomic status, and children’s cognitive-social competence at school entry. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 54, 459-468.

Guidubaldi, J., & Perry, J. D. (1985). Divorce and mental health sequelae for children: A two-year follow-up of a nationwide sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 24, 531-537.

Guidubaldi, J., Perry, J. D., & Cleminshaw, H. K. (1984). The legacy of parental divorce: A nationwide study of family status and selected mediating variables on children’s academic and social competencies. In B. B. Lahey & A. E. Kazdin (Eds.), Advances in clinical child psychology (Vol. 7, pp. 109-151). New York: Plenum Press.

Hetherington, E. M. (1972). Effects of parental absence on personality development in adolescent daughters. Developmental Psychology, 78, 313-326.

Hetherington, E. M. (1987). Family relations six years after divorce. In K. Pasley & M. Ihinger-Tallman (Eds.), Remarriage and stepparenting today: Research and theory (pp. 185-205). New York: Guilford Press.

Hetherington, E. M. (1991a). Families, lies, and videotapes. Journal of Research on Adolescence, I, 323-348.

Hetherington, E. M. (1991b). The role of individual differences and family relationships in children’s coping with divorce and remarriage. In P. A. Cowan & M. Hetherington (Eds.), Family transitions (pp. 165-194). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Hetherington, E. M. (1993). An overview of the Virginia Longitudinal Study of Divorce and Remarriage with a focus on early adolescence. Journal of Family Psychology, 7, 39-56.

Hetherington, E. M., & Anderson, E. R. (1987). The effects of divorce and remarriage on early adolescents and their families. In M. D. Levine & M. D. McAnarney (Eds.), Early adolescent transitions (pp. 49-67). Lexington, MA: D. C. Heath.

Hetherington, E. M., & Camara, K. A. (1984). Families in transition: The process of dissolution and reconstitution. In R. D. Parke (Ed.), Review of child development research: The family Vol. 7 (pp. 398-439). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hetherington, E. M., Camara, K. A., & Featherman, D. (1983). Achievement and intellectual functioning of children in one-parent households. In J. Pence (Ed.), Assessing achievement (pp. 206-284). San Francisco: W. H. Freeman.

Hetherington, E. M., & Clingempeel, W. G. (1992). Coping with marital transitions. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development (Vol. 57, No. 2-3, Serial No. 227).

Hetherington, E. M., Cox, M., & Cox, R. (1978). The development of children in mother-headed families. In H. Hoffman & D. Reiss (Eds.), The American family: Dying or developing? (pp. 117-145). New York: Plenum Press.

Hetherington, E. M., Cox, M., & Cox, R. (1979). Play and social interaction in children following divorce. Journal of Social Issues, 35, 26-49.

Hetherington, E. M., Cox, M., & Cox, R. (1982). Effects of divorce on parents and children. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), Nontraditional families: Parenting and child development (pp. 233-288). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Hetherington, E. M., Cox, M., & Cox, R. (1985). Long-term effects of divorce and remarriage on the adjustment of children. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 24, 518-530.

Hetherington, E. M., Stanley-Hagan, M., & Anderson, E. R. (1989). Marital transitions: A child’s perspective. American Psychologist, 44, 303-312.

Johnston, J. R., Campbell, L. E. G., & Mayes, S. S. (1985). Latency children in post-separation and divorce disputes. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 24, 563-574.

Kalter, N. (1977). Children of divorce in an outpatient psychiatric population. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 47, 40-51.

Kalter, N., Riemer, B., Brickman, A., & Chen, J. W. (1985). Implications of divorce for female development. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 24, 538-544.

Kelly, J. B. (1988). Longer-term adjustment in children of divorce: Converging findings and implications. Journal of Family Psychology, 2, 119-140

Klein, R. G., & Manhuzza, S. (1991). Long-term outcome of hyperactive children: A review. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 30, 383-387.

Kogan, L., Smith, J., & Jenkins, S. (1977). Ecological validity of indicator data as predictors of survey findings. Journal of Social Science Research, 1, 117-132.

Kurdek, L. A., Blisk, D., & Siesky, A. E., Jr. (1981). Correlates of children’s long-term adjustment to their parent’s divorce. Developmental Psychology, 17, 565-579.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer.

Lewis, J. M., & Wallerstein, J. S. (1987). Family profile variables and long-term outcomes in divorce research: Issues at a ten-year follow-up. In J. P. Vincent (Ed.), Advances in family intervention, assessment and theory (Vol. 4, pp. 121-142). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Lewis, S. A., Gorsky, A., Cohen, P., & Hartmark, C. (1985). The reactions of youth to diagnostic interviews. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 24, 750-755.

Loeber, R., & Dishion, T. (1983). Early predictors of male delinquency: A review. Psychological Bulletin, 94, 68-99.

Luepnitz, D. A. (1979). Which aspects of divorce affect children. Family Coordinator, 28, 79-85.

Luepnitz, D. A. (1986). A comparison of maternal, paternal and joint custody: Understanding the varieties of post-divorce family life. Journal of Divorce, 9, 1-12.

Maccoby, E. E., Buchanan, C. M., Mnookin, R. H., & Dornbusch, S. M. (1993). Postdivorce roles of mothers and fathers in the lives of their children. Journal of Family Psychology, 7, 24-38.

Mannuzza, S., Klein, R. G., Bonagura, N., Malloy, P., Giampino, T. L., & Addalii, K. A. (1991). Hyperactive boys almost grown up. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48, 77-83.

Newcomer, S., & Udry, J. (1987). Parental marital status effects on adolescent sexual behavior. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 49, 235-240.

O’Leary, K. D., & Emery, R. E. (1984). Marital discord and child behavior problems. In M. D. Levine & R. P. Satz (Eds.), Middle childhood: Development and dysfunction (pp. 345-364). Baltimore: University Park Press.

Olweus, D. (1980). Familial and temperamental determinants of aggressive behavior in adolescent boys: A causal analysis. Developmental Psychology, 16, 644-660.

Peterson, J. L., & Zill, N. (1983, April). Marital disruption, parent-child relationships, and behavioral problems in children. Paper presented at the meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Detroit.

Peterson, J. L., & Zill, N. (1986). Marital disruption, parent-child relationships, and behavior problems in children. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 48, 295-307.

Plomin, R. E. (1993). Interface of nature and nurture in the family. In W. B. Carey & S. C. McDevitt (Eds.), Prevention and early intervention: Individual differences as risk factors for the mental health of children (pp. 179-189).

Reid, W. J., & Crisafulli, A. (1990). Marital discord and child behavior problems: A meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 18, 105-117.

Reinhard, D. W. (1977). The reaction of adolescent boys and girls to the divorce of their parents. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 2, 21-23.

Rutter, M. (1970). Sex differences in children’s responses to family stress. In E. J. Anthony & C. Koupernik (Eds.), The child in his family (pp. 165-196). New York: Wiley.

Rutter, M. (1983). Stress, coping, and development: Some issues and some questions. In N. Garmezy & M. Rutter (Eds.), Stress, coping and development in children, New York: McGraw-Hill.

Rutter, M. (1987). Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 57, 316-331.

Santrock, J. W., Warshak, R. A., Lindberg, C., & Meadows, L. (1982). Children’s and parents’ observed social behavior in stepfather families. Child Development, 53, 472-480.

Thomas, A., & Chess, S. (1980). The dynamics of psychological development. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Thomas, A., Chess, S., & Birch, H. G. (1968). Temperament and behavior disorders in children. New York: New York University Press.

Velez, C. N., Johnson, J., & Cohen, P. (1989). A longitudinal analysis of selected risk factors for childhood psychopathology. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 28, 861-864.

Wallerstein, J. S. (1985). Children of divorce: Preliminary report of a ten-year follow-up of older children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 24, 545-553.

Wallerstein, J. S. (1987). Children of divorce: Report of a ten-year follow-up of early latency-age children. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 57, 199-211.

Wallerstein, J. S. (1991). The long-term effects of divorce on children: A review. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 30, 349-360.

Wallerstein, J. S., & Kelly, J. (1980). Surviving the break-up: How children actually cope with divorce. New York: Basic.

Weiss, R. (1979). Growing up a little faster: The experience of growing up in a single-parent household. Journal of Social Issues, 35, 97-111.

Zaslow, M. J. (1988). Sex differences in children’s response to parental divorce: 1. Research methodology and postdivorce family forms. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 58, 355-378.

Zaslow, M. J. (1989). Sex differences in children’s response to parental divorce: 2. Samples, variables, ages, and sources. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 59, 118-140.

Zaslow, M. J., & Hayes, C. D. (1986). Sex differences in children’s response to psychosocial stress: Toward a cross-context analysis. In M. E.

Lamb, A. Brown, & B. Rogoff (Eds.), Advances in developmental psychology (Vol. 4, pp. 285-337). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Zill, N., Morrison, D. R., & Coiro, M. J. (1993). Long-term effects of parental divorce on parent-child relationships, adjustment, and achievement in young adulthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 7, 91-103.