Overview of Diabetes

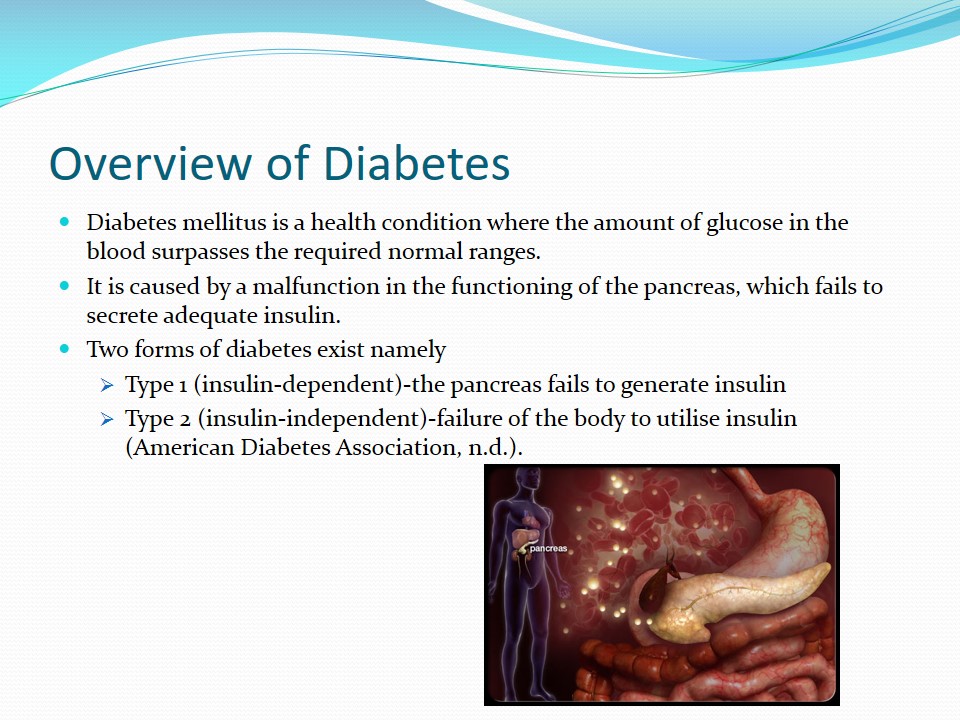

- Diabetes mellitus is a health condition where the amount of glucose in the blood surpasses the required normal ranges.

- It is caused by a malfunction in the functioning of the pancreas, which fails to secrete adequate insulin.

- Two forms of diabetes exist namely:

- Type 1 (insulin-dependent)-the pancreas fails to generate insulin.

- Type 2 (insulin-independent)-failure of the body to utilise insulin (American Diabetes Association, n.d.).

Juvenile Type 1 Diabetes

- This is the form of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus that occurs in children and adolescents.

- The precise cause of juvenile type 1 diabetes is unknown.

- However, the immune system plays a role in the development of the condition.

- Genetics also influence the development of the disease.

- The main indications of insulin-dependent diabetes in children comprise:

- Increased need for water;

- Regular urges to pass urine;

- Extreme food cravings.

- Other symptoms include:

- Weight loss;

- Exhaustion and weariness;

- Irritability and sudden mood changes;

- Blurred vision (Majeed & Hassan, 2011).

Risk Factors

- There are two key risk factors for juvenile type 1 diabetes.

- Genetics- the presence of the HLA genes (human leucocyte antigen) increases the likelihood of developing the condition.

- Family history- individuals with parents or siblings with type 1 diabetes are more prone to developing the condition than those without a family history of the disease.

- Other risk factors include:

- Viral infections-Epstein-Barr virus, rubella and Coxsackie stimulate the immune system to generate autoantigens that destroy the islet cells (Majeed & Hassan, 2011).

- Ethnicity-Whites are more susceptible to type 1 diabetes than Blacks and Hispanics.

- Diet-Previously, it was thought that an intake of vitamin D lowered the chances of having the condition (Hyppönen, Läärä, Reunanen, Järvelin, &Virtanen, 2001). However, it has been established that feeding infants with cow’s milk (a rich source of vitamin D) increases their chances of developing diabetes (Casu, Pascutto, Bernardinelli, The Sardinian IDDM Epidemiology Study Group, & Songini, 2004).

- Obesity and rapid linear growth correlates with the incidences of type 1 diabetes (Hyppönen et al., 2000).

- The presence of elevated blood sugar levels and the typical diabetes symptoms must be established to identify diabetes. (American Diabetes Association, n.d.).

- The provision of care in diabetic children ought to keep in mind the disparities between kids and adults, and should be tailored to the age of the patient.

- Education needs to include the patient’s parent or caregiver.

- The management of type 1 diabetes involves the integration of insulin therapy into the individual patterns of diet and physical activity (American Diabetes Association, 2007).

- About 30% of all children with newly-diagnosed type 1 diabetes usually suffer from diabetic ketoacidosis and should be treated (Diabetes UK, 2013).

- Children without life-threatening symptoms are released and cared for in the comfort of their homes.

The education ought to call attention to age and developmentally suitable self-care, which should gradually empower the children to take care of themselves as they progress from childhood to adolescence and into adulthood.

North West England

- The region comprises one of the most socially deprived regions of England (Harwood, Mytton, & Watkins, 2004).

- The region comprises diverse ethnic groups including Asians and Blacks. Whites make up 94.4% of the population while other races make up 5.6%.

- 2.2% of people in North West England are living with type 1 diabetes.

- A large proportion of people in the region comprises skilled, partly skilled and unskilled manual workers while a tiny proportion works in professional, managerial and technical positions.

- Several studies indicate that there is a strong association between social deprivation and the prevalence of diabetes (Lopez, Mathers, Ezzati, Jamison, & Murray, 2006).

- Therefore, it is expected that the incidence of chronic illnesses such as diabetes is high in such regions.

The Needs of the Population

- There is inadequate knowledge on the management of diabetes among the people of North West England, which can be attributed to the social class of a majority of the populace.

- The lack of adequate knowledge regarding the condition leads to poor management of the condition and leads to the underutilisation of preventive services.

- The Pakistani women living in North West England have inferior glycaemic control practices and know-how of self-monitoring due to their poor educational backgrounds.

- The population of North West England does not have adequate care for diabetic patients.

- Therefore, the National Service Framework for Diabetes has established a few policies to guide the delivery of proper health care to all diabetic patients.

- All diabetic children are set to get assistance and attention to improve the regulation of their blood glucose levels.

- The support aims at improving their bodily, mental, academic, didactic, and social development (Harwood, Mytton, & Watkins, 2004).

Incidences of Juvenile Type 1 Diabetes

- The total number of children under seventeen years living with type 1 diabetes in North West England by 2009 was 2,630 out of the 1,498,716 of children under the age of 17 in the region (Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, 2009).

- The incidence translated to a prevalence rate of 175.5 out of every 100,000 children aged seventeen and below.

- The prevalence was slightly lower than the expected incidence of 2,792.7 using the overall prevalence of type 1 diabetes in the entire country.

- Out of the 2630 children with type 1 diabetes, 97 fell in the age group of 0 to 4 years while 527 fell between the ages of 5 and 9 years.

- 1153 of the children were between the ages of 10 and 14.

- 302, 338 and 213 children were aged 15, 16 and 17 respectively.

- The age-related prevalence (per 100,000 population) of the disease in the region was:

- 24.1 among children between the ages of 0 and 4 years.

- 218.7 among those aged between 5 and 15 years.

- 290.1 among teenagers between 16 and 17 years.

- The numbers of school-going children were:

- 2,042 for the ages between the ages of 5 and 15.

- 575 for those aged between 16 and 17.

Risk Factors and Access to Services

- Risk factors for juvenile type 1 diabetes in northwest England include:

- Ethnicity;

- Smoking;

- Genetics;

- Access to services:

- Children living with type 1 diabetes receive specialized care from paediatricians who are well-versed with endocrinology and diabetes.

- Most of these professionals are also members of diabetic organisations (Harwood, Mytton, & Watkins, 2004).

- The personnel involved include medics, nurses, the management, book-keeping staff, and allied health professionals such as dieticians.

- In the UK, a number of groups have been developed to help the population cope with the incidences of type 1 diabetes. An example is the Dose Adjustment for Normal Eating (DAFNE) group, which was first established in Germany. The group provides an effective inpatient instructive program for type 1 diabetes patients.

Ethnicity -a large number of people hospitalized for type 1 diabetes-related complications come from multicultural centres.

Smoking- 15% of professionals in North West England are smokers while 42% of the manual labourers are smokers.

Though children do not smoke, they are exposed to secondary smoke from their parents in their homes and other surroundings.

Fatness-A large proportion of the children in northwest England is obese hence elevating the chances of having type 1 diabetes.

Genetics and family history also increase the chances of developing type 1 diabetes in the region.

Intervention Strategy and the Reduction of Type 1 Diabetes Disease Burden and Inequalities

Children and young people living with diabetes ought to have access to the best medical care that gives them the power to handle their condition on a daily basis.

They ought to receive specialized care that goes farther than hospital settings to ensure that they can lead their daily lives in a manner that is clinically favourable and psychologically appropriate.

The most appropriate intervention strategy to lower the problem of juvenile type 1 diabetes among children and adolescents in North West England is the provision of diabetic children and their families with adequate education on the disease.

The importance of education has been established in numerous studies involving children, adolescents as well as adults.

Evidence of the Effectiveness of Education in the Management of Type 1 Diabetes

- Proper education of families of children with type 1 diabetes leads to a substantial decline in incidences of hospitalization of children with the condition.

- These measures have reduced instances of emergency hospital visits and the overall cost of treatment.

- The success of patient education in the management of adult type 1 diabetes has been extrapolated into the management of diabetes in children.

- In a proposed randomized pragmatic clinical trial, George et al. (2007) suggested the use of Brief Intervention in Type 1 diabetes: Education for Self-efficacy (BITES).

- In the actual trial, George et al. (2008) enlisted the treatment group into educational sessions that extended for six weeks during which the patients were able to reflect and practice the knowledge gained.

- The intervention led to an improvement in diabetes treatment contentment. In addition, the patients were empowered to handle their diabetic condition in a better way.

- Similar findings were recorded by Couch et al. (2008).

Components of Education

- A comprehensive education program should consider the individual and cultural needs of the patient.

- The program also needs to consider the patients’ siblings who may feel disregarded due to increased attention paid to the patient because of the new diagnosis (NHS Diabetes, 2010).

- The information and mode of delivery need to be suited to paediatric needs.

- The family should not be burdened with many details on the management of the disease immediately after diagnosis because they may still be in shock or angered by the life-changing diagnosis (Silverstein et al., 2005).

- Some of the components of the education include:

- Continued education:

- Regular education and support to ensure the children develop more elements of self-care as they grow (Daneman, 2006).

- Sessions can be flexible to allow diabetic adolescents to come along with their close friends for peer support (Greco, Pendley, McDonell, & Reeves, 2001).

- Adolescents with diabetes often experience bodily, emotional, mental strain because of the pressure of a complex medical routine (Davidson, Penney, Muller, & Grey, 2004).

- Continued education:

- Self-management is the foundation of effectual preventative care in diabetes.

- Factors such as age, cognitive capabilities, emotive maturation, and the motor advancement of the patients influence their capacity to take part in self-management of diabetes.

- Blood glucose monitoring and glycaemic control:

- The management of type 1 diabetes seeks to keep blood sugar levels within the acceptable ranges.

- During adolescence, the numerous changes that occur lead to insulin resistance hence necessitate higher doses of insulin.

- It has been reported that HbA1c levels in diabetic adolescents are one percent higher than in other diabetic patients (Australasian Paediatric Endocrine Group, 2005).

- Education sessions prepare adolescents psychologically certain changes that affect their blood glucose levels.

- Parental presence is vital throughout to guarantee proper self-management and metabolic regulation.

- It is vital that certain self-management capabilities are present at various developmental stages.

- The use of insulin in the management of diabetes

- Insulin doses are determined by the age, weight and state of puberty.

- Younger children require small doses while older ones need elevated insulin doses due to hormonal alterations at puberty.

- Advice on the preparation and administration of insulin is provided during educational sessions for diabetic patients.

- Nutrition advice focuses on:

- Achieving blood glucose objectives devoid of extreme hypoglycaemia.

- Average growth and development, as well as lipid and blood pressure targets.

- These objectives can be attained through personalized meal planning and adaptable insulin routines and algorithms.

HbA1c is the ultimate yardstick for evaluating the control of diabetes. Reduced levels of HbA1c correspond to a low incidence of microvascular complications .

Implementation of the Intervention

- The implementation of patient education as a measure to manage juvenile type 1 diabetes is achieved with the help of various bodies.

- Successful outcomes can be realized with the help of organisations as well as local, national and professional bodies (Martin, Liveley, & Whitehead, 2009).

- Local intervention:

- A local diabetes network has been established in North West England as stipulated by the National Services Framework for Diabetes.

- This network finds local leaders and chooses network managers, clinical champions and diabetic patients to champion the views of the local people.

- A local diabetes list and research unit have been established to recognize main areas for future research in the improvement of diabetes services to the people of North West England.

- Professional intervention:

- Carried out by the health professionals that provide the education.

- These professionals include endocrinologists, dieticians, nurses, and mental health care professionals.

- They schedule appointments with the patients and their families once in a while to monitor the progress of the patient and advise accordingly (Harwood, Mytton, & Watkins, 2004).

- National implementation:

- Initiatives such as “Saving Lives: Our Healthier Nation” are in place to establish national paradigms and outline service models to promote health.

- The British Society for Paediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes promote the education of paediatric endocrinology hence helping children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes.

- The Department of Health in the UK has authorized the Research Division of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) to carry out a study to determine the population of diabetic children.

- Other organisations such as the Royal College of Nursing, the Association of Children’s Diabetes Clinicians and the NHS Diabetes among many others are also part of the study.

- Organisational implementation:

- Organisations such as Diabetes UK oversee endeavours to promote the education of children with diabetes to enable them to lead productive lives.

- The NHS undertakes local and national appraisal of diabetic services.

- The members of staff involved in the provision of care to diabetic patients undergo training to improve and advance their health care delivery skills.

- The Local Workforce Development Confederation takes part in the development of learning and training curricula for diabetic patients (Harwood, Mytton, & Watkins, 2004).

Resources

- Databases used included the general Google search engine and Google scholar database.

- The search terms used included:

- Diabetes mellitus;

- Type 1 diabetes;

- Juvenile type 1 diabetes;

- Juvenile type 1 diabetes in North West England;

- Intervention against juvenile type 1 diabetes in North West England.

- There were millions of results after the searches. However, relevant sources were selected from the first 20 results of each search.

References

American Diabetes Association. (n.d.). Diagnosing diabetes and learning about pre-diabetes. Web.

American Diabetes Association. (2007). Nutrition recommendations and interventions for diabetes: A position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care, 30 (Supplement1), S48-S65.

Australasian Paediatric Endocrine Group. (2005). Clinical practice guidelines: Type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents. Web.

Casu, A., Pascutto, C., Bernardinelli, L., The Sardinian IDDM Epidemiology Study Group, & Songini, M. (2004). Type 1 Diabetes among Sardinian children is increasing. Diabetes Care, 27(7), 1623–1629.

Couch, R., Jetha, M., Dryden, D. M., Hooton, N., Liang, Y., Durec, T., Sumamo, E., Spooner, C., Milne, A., O’Gorman, K., & Klassen, T. P. (2008). Diabetes education for children with type 1 diabetes mellitus and their families. Web.

Daneman, D. (2006). Type 1 diabetes. The Lancet, 367(9513), 847-858.

Davidson, M., Penney, E. D., Muller, B., Grey, M. (2004). Stressors and self-care challenges faced by adolescents living with type 1 diabetes. Applied Nursing Research, 17(2), 72–80.

Diabetes UK. (2013). Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). Web.

George, J. T., Valdovinos, A. P., Thow, J. C., Russell, I., Dromgoole, P., Lomax, S., Torgerson, D. J., & Wells, T. (2007). Brief Intervention in Type 1 diabetes – Education for Self-efficacy (BITES): Protocol for a randomised control trial to assess biophysical and psychological effectiveness. BMC Endocrine Disorders, 7(6), 1-5.

George, J. T., Valdovinos, A. P., Thow, J. C., Russell, I., Dromgoole, P., Lomax, S., Torgerson, D. J., Wells, T., & Thow, J. C. (2008). Clinical effectiveness of a brief educational intervention in Type 1 diabetes: Results from the BITES (Brief Intervention in Type 1 diabetes, Education for Self-efficacy) trial. Diabetic Medicine, 25(12), 1447–1453.

Greco, P., Pendley, J. S., McDonell, K., & Reeves, G. (2001). A peer group intervention for adolescents with type 1 diabetes and their best friends. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 26(8), 485–490.

Harwood, C., Mytton, J., & Watkins, F. (2004). Diabetes and inequalities in the North West of England. Liverpool: University of Liverpool.

Hviid, A., Stellfeld, M., Wohlfahrt, J., & Melbye, M. (2004). Childhood vaccination and type 1 diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine, 350(2004), 1398-1404.

Hyppönen, E., Läärä, E., Reunanen, A., Järvelin, M-R., &Virtanen, S. M. (2001). Intake of vitamin D and risk of type 1 diabetes: a birth-cohort study. The Lancet, 358(9292), 1500 – 1503.

Hyppönen, E., Virtanen, S. M., Kenward, M. G., Knip, M., Akerblom, H. K., & Childhood Diabetes in Finland Study Group. (2000). Obesity, increased linear growth, and risk of type 1 diabetes in children. Diabetes Care,23(12), 1755-1760.

Lopez, D. A., Mathers, C. D., Ezzati, M., Jamison, D. T., & Murray, C. J. L. (2006). Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: Systematic analysis of population health data. The Lancet, 367(9524), 1747 – 1757.

Majeed, A. A. S. & Hassan, K. (2011). Risk factors for type 1 diabetes mellitus among children and adolescents in Basrah. Oman Medical Journal,26(3), 189–195.

Martin, C., Liveley, K., & Whitehead, K. (2009). A health education group intervention for children with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Diabetes Nursing, 13(1), 32-37.

NHS Diabetes. (2010). National Service Framework for Children, Young People and Maternity Services – Type 1 diabetes in childhood and adolescence. Web.

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. (2009). Growing up with Diabetes: Children and young people with diabetes in England. Web.

Silverstein, J., Klingensmith, G., Copeland, K., Plotnick, L., Kaufman. F., Laffel, L., Deeb, L., Grey, M., Anderson, B., Holzmeister, L. A., &Clark, N. Care of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes: A statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care, 28(1), 186-211.