Introduction

Community-based Intervention in the context of health is a vital concern often ignored in most organizations and even hospitals, which hold the notion of health promotion. Because of the reason that Community-based interventions (CBI) are funded by public health departments, federal, state, or local governments, and private foundations, CBI lack a healthy lifestyle that has its requirements. The priority in CBI must be to consider the various factors, which are responsible for leading a healthy life free from any impurity. In this context, all that can be done is to hire reformers so that they can take interest in the concept of a ‘community health center’, which is a form of group practice. In other words, CBI relies on teamwork among professionals doctors, and others, which focuses on prevention of illness and promotion of health and works with a community board.

Community-Based Intervention

The area of study of my health promotion plan is a community-based (or population-based) intervention to initiate research outside traditional clinical settings such as hospitals or clinics. This research is primarily aimed at promoting health or preventive health practices at the community level. Most of these interventions are intended to change behavior, although some may focus on screening for undetected clinical problems. I envision such interventions as those traditionally undertaken by public health departments, ‘community’ offices of hospitals, private health care systems including health maintenance organizations (HMOs), community-based organizations, or even churches. (Derose et al, 1998, p. 4) Community-based research also includes parenting classes run by a community-based setting, radio announcements to discourage smoking, or a program at a senior center that promotes arthritis screening.

In recent years, health promotion has modified itself so that it may be easier to make clinical decisions based on patient care and so have come to rely more and more on the best available scientific evidence regarding the effectiveness of a given procedure or drug. How might the evidence-based approach be adapted to support decision-making for community-based health interventions? Would such an approach be feasible and helpful? In this report, we seek to answer these questions.

Health Promotion Priority

The paradigm of evidence-based medicine (EBM) is the highest health promotion authority currently practiced largely by clinical researchers in European nations particularly in England, where EBM has been described as the painstaking, unambiguous, and carefully designed domain which not only utilizes current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients (Sackett et al., 1996) but also proposes five elementary health care research techniques to the paradigm (Sackett and Rosenberg, 1995):

- Research Evidence –Clinical intervention along with various other health care decisions are based on the notion of best patient-level which is population-based, and according to laboratory evidence.

- Evidence Setting –Every clinical problem other than habits, procedures, and traditions, determines the evidence set to be sought.

- Identification – Identifying the best evidence calls for the integration of epidemiological and biostatistical ways of thinking with those derived from pathophysiology and personal experience.

- Conclusion –The conclusions of the research are beneficial if and only the critical appraisal of evidence are worthwhile and are implemented into practice that affects patients.

- Evaluation – Continuous evaluation and assessment of performance.

Approaches to Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM)

EBM performs dual tasks at a time. On one hand, it makes wise use of modern best evidence in making choices about the care of individual patients while on the other it practices and applies techniques and researches of EBM thereby combining individual clinical expertise with the finest proven available evidence from systematic research. EBM and other ‘evidence-based undertakings have taken the medical community and health care by storm. Many positive, even enthusiastic commentaries and analyses have appeared in the medical press and elsewhere. EBM ‘came as a gift from the gods, in the words of Sir David Weatherall (Greenhalgh 2001). There are various kinds of community or organizational approaches used in the context of EBM which include: Evidence-based nursing (EBN), evidence-based practice (EBP), and evidence-based health economics (EBHE).

Need for applying an evidence-based approach to Community Setting

The first and foremost reason for the application of the EBM approach to the community setting is the spread of managed care as health care systems are becoming increasingly oriented toward caring for defined populations rather than individual patients. This shift in focus has forced health care systems to consider implementing comprehensive health-promoting population at community-level interventions as a natural and potentially cost-effective complement to individual health services. Many of the most costly health care problems are intimately tied to health-related behaviors, such as smoking and exercise. Community health interventions may be a cost-effective way to promote changes in such behavior before individuals enter the health care system with clinical disease.

Second, with the push to control costs, health care systems are confronting growing pressures for choosing wisely in allocating their limited resources to promote health. Most large health care systems are already involved in a range of community-based health interventions, although typically these programs are not considered an integral part of their primary mission. An evidence-based approach helps in directing increasingly scarce resources to activities that have their desired effect and are efficient. (Derose et al, 1998, p. 5).

Third, there is evidence of increasing barriers in health between those with high socioeconomic status and those with low socioeconomic status (Pappas et al., 1993). Like in community settings majority of the population is hand to mouth and rarely meets all their needs. Furthermore, due to the challenges confronted by the health care system experts, third-party insurers, and government agencies, tighter resource limitations do not always grant access to health care. This is likely to become more difficult for certain populations, particularly the uninsured and, among those, immigrants. Foundations and other funders may feel motivated to try closing some of these gaps and, like other health care funders, will want to make the most of what they have. They will thus also need evidence of what works best among preventive community interventions.

Processes used to determine the need

Need determination is often labeled as formal procedures or qualitative evaluations It is due to the assessments made we have come to know the community’s major problems. Though difficult to assess, need attributions about specific results of interventions are often not backed by sufficient evidence to warrant acceptance of the conclusion. For example, one study of a community-based health promotion program mentioned that religious gathering tended to be the most effective means of reaching the target audience, yet offered no evidence to support that claim (Doyle et al., 1989). I believe such means are not necessary to reach people, as it is enough to meet and understand their primary concerns of leading lives. However most of the researches negate the view on providing evidence of effect; some provided simply no evidence, quantitative or qualitative, of effect.

Besides qualitative evaluations, self-reported behavior is another way of determining need. This involves individual questioning from individuals concerning gender, age and income effect. This may not provide an accurate picture of behavior because participants may be inclined to give what they consider to be desired answers. Standardized measures of outcomes such as biochemical markers of smoking or even more remote outcomes such as morbidity are more expensive and maybe inappropriate or impractical in a community setting (Fishbein, 1996). However, alternative measures, such as measures of behavioral or attitude change, are more reliable as compared to the above mentioned for most community health interventions. Nevertheless, the strength of the evidence of community health interventions will almost certainly improve with the broadened use, when feasible, of more objective and valid measures of the desired outcomes.

While determining need, one can evaluate the need for guides as to the appropriateness of various outcome measures for different types of community health interventions. These are the standards that facilitate the assessment and effectiveness of the evidence in community settings. Even relevancy is also considered that uses valid measures, with similar outcomes which are varied with the study with resource use unreported. This obstructs substantive comparisons among and across various interventions or explicit comparisons of costs versus effectiveness or benefit. (Derose et al, 1998, p. 16) For example, if a community-based organization wants to choose between a school-based intervention targeted at drug abuse and a community-wide intervention to target HIV prevention, the literature as it currently exists would not provide much guidance. The reason is the standard followed by the outcome measures and the provision of cost data which substantially improve the ability of a community-based organization to make such choices.

Relationship to Wellness or ill Health

In the past communities have been described by various research groups among which Howell and Dyck have developed around the profound sentiments, anxieties, and hopes of childlessness and parenting, experiences which are no less emotionally charged and collectively constructed than aging, family, consubstantial relation with land or a sense of a long shared history. (Amit, 2002, p. 37).

Apart from the above social conditions, community upholds the relationship between wellness and ill health based on partiality and episodicity and are not synonymous with triviality and superficiality, and, as Dyck notes, community need not be all-encompassing or directive to provide satisfying forms of social connection and belonging. Indeed, however much they may differ in terms of historical depth, the range of activities they comprise, or their duration, none of the communities described are all-encompassing. In all these cases, they organize and express only some of the attachments, activities, and identities in which their participants are engaged. None, therefore, constitute the ‘terminal identities’ once ascribed by A. L. Epstein to ethnicity (1978). We could argue therefore that the relational character of the community is as likely to be derived from the multiple attachments of its members as from contrasts with collectivities in which they are not members.

Grossman (1972) developed an economic model of an individual’s health behavior, or demand for health, based on the household production model (Becker, 1965). The reason was to identify the relationship between model and wellness. Therefore by using a utility-maximizing framework, Grossman showed that an individual’s behavior concerning expected health change is determined by the balancing of the benefits and opportunity costs of health change. One of many applications of this model over the past 30 years is Ehrlich’s explanation of the systematic diversity in life expectancies across populations and the observed wide variability in empirical estimates of the valuation of life-saving programs (Ehrlich 2000). Under Grossman’s model, benefits incorporate two components: consumption (the direct change in well-being associated with the change in health – feeling healthier or less healthy) and investment (the impact of health change on other aspects of the individual’s life – health change might affect an individual’s income-earning capacity or the capacity to engage in leisure activities, etc.). These are measured in terms of the individual’s valuation of these ‘consequences’ of health change.

Target groups

In terms of the target population, about two-thirds of the interventions usually target children or adolescents with the remaining spread among the elderly, the general population, young adults, and subpopulations with specific diseases. We have targeted the elderly concerning social conditions and economic needs. About half of the interventions are implemented in an educational setting i.e., a primary or secondary school or college. The remainder are broad community interventions (e.g., public health promotion media campaigns)

The focus of most community health interventions is on behaviors that affect health. The specific behaviors of interest varied widely across the studies, with drug and alcohol abuse being most common; others included injuries and violence, HIV prevention, cardiovascular risks, nutrition, and weight loss, and exercise. For example, profound research assessed the effect of a community-wide intervention program experimenting with various strategies to reduce alcohol-impaired driving, driving risks, traffic deaths, and injuries (Hingson et al., 1996). Similarly, two relevant studies after evaluating the need for health screening and promotion projects whose primary goal was the identification of disease rather than behavioral change (Rogers et al., 1992) implemented its’ projects in community settings, they perhaps should have been eliminated from review because of their more clinical focus.

Planning Approaches

Among planning approaches, various evidence reveals that cost-effectiveness is not the only reason that obstructs deciding in community-based programs as analyses are not commonly used in taking decisions. Other reasons include fund-raising, lack of federal or provincial support, etc. A few of those interviewed did say that they relied on cost-effectiveness, which they most often defined as cost per client served. Even so, at least one of these admitted that the cost per client is not the bottom line and that for some programs the decision-making and evaluation tend to ‘respond on an emotional level’ (i.e., how effective is the program on a qualitative level). Other foundation representatives uphold the opinion that the health and managed care perspective causes them to pay more attention to cost-effectiveness. Foundation personnel also recognize the need for evidence if they hope to ultimately affect policy. (Derose et al, 1998, p. 33).

For both foundations and health systems, funding priorities are affected by strategic planning. Those interviewed were generally committed to strategic planning, though foundations’ experience with it varies. Several reports relying on their board, which represents the community, to make the decisions and set the course. Several organizations cited examples of how they use data in planning, such as developing a profile of health problems in the county to compare them to state and national profiles to see where health problems are not being addressed. Indeed, current trends local and national are playing an increasing role in determining priorities. For example, managed care and health finance policy reforms were mentioned by all organizations as important factors affecting their funding priorities. It also seemed important to some that they identify needs that are not being met by other foundations and programs.

The approaches we have adopted for the community’s well-being revolve around their health and social conditions. This is because of the qualitative research we conducted and found that in a population of 37,000 people, kids comprised 40%, women 35%, and men 25%. Among which 20% were aged between 55-80 years. In this respect, we planned our community project so that every individual could benefit from the measures taken.

Framework of Evaluation

Hospitals in rural community settings are surveyed every fifteen days to get detailed information about the patient’s history. This includes a percentage of patients of a particular disease keeping in mind the following concerns: weather conditions, sanitation, and cleanliness of the surrounding areas. Practitioners are asked to document the family history and the living standards of every patient in detail.

DiCenso et al. (1998) state that the evaluation of nursing interventions and the understanding of patients’ experiences have to be investigated by different research methods. RCTs, meta-analyses, and systematic reviews are the best designs for evaluating nursing interventions, while qualitative studies (interviews) are to be preferred to gain a better understanding of patients’ experiences. The latter is particularly useful in exploring and explaining the barriers to patient compliance, how a treatment affects patients’ everyday life, the meaning of illness to the patient, etc. The idea of RCTs, patient analyses, and review research as the ‘gold standard’ methods of assessing the effectiveness of treatment methods and nursing interventions is based on the assumption that systematic reviews provide nurses with a summary of all the tools and techniques used during research on a specific topic. (Kristiansen & Mooney, 2004, p. 35).

Faced with continual increases in the cost of drugs under the program and the need to make sure that resources were being used efficiently, the Quality control adopted an evidence-based approach to the development of its recommendations. The recommendations are based on the economic evaluation of the drugs under consideration, and follow guidelines for the economic evaluation of new technologies published a decade earlier (Laupacis et al. 1992). In this way, the work of the committee would seem to represent EBHE. The evaluation involves a comparison of the new drug with the current way of treating the patient group for whom the new drug is being proposed, and is summarised in the estimated value of the ICER. The ICER is calculated by dividing the difference in costs between new and old treatments by the difference in effects to give the additional cost per unit outcome.

Issues influencing Health Promotion

Donaldson et al. (2002) describe economics as one of the most influential issues of health promotion. It would be better to say that evidence-based health economics (EBHE) is the most profound barrier in the application of ‘evidence-based principles’ of health promotional objectives. (Donaldson et al, 2002).

Two factors have identified that influence EBHE while distinguishing it from other evidence-based approaches. First, the scope of problems addressed by EBHE is much broader than for other areas of the evidence-based approach, such as evidence-based medicine (EBM). Under EBM, interest is confined to individual health care interventions and the clinical consequences of those interventions in community settings. EBHE complements EBM by contributing information on the economic consequences of interventions in the form of the net change in resources used and the impact, in terms of other benefits forgone as a result of taking resources from elsewhere to support a particular intervention.

In economics, these forgone benefits represent the opportunity cost of the intervention. However, EBHE can also be applied to a wide range of economic issues beyond individual health care interventions concerning the production, protection, and restoration of health in populations. So, the application of economics is not confined to whether a particular intervention represents an efficient use of resources. Economics can also be used to consider whether the current method of physician remuneration is the best way of ensuring that physicians prescribe this intervention, as opposed to the alternative, less efficient interventions, to the right people at the right time.

Having established these defining characteristics, the authors return to the focus on economic evaluations of clinical interventions and the important notion of systematic reviews. In other words, although the inclusion of economics in the evidence-based approach provides a resource context to the evidence base, and broadens the focus of attention beyond clinical interventions, the nature of the question being considered remains academically driven. For example, EBHE would include consideration of the outcomes of different methods of paying health care providers, e.g. capitation versus service fee. But the underlying question of EBHE remains contextual – that is, from an economic perspective, does substitute capitation payment for fee-for-service payments ‘work on average’.

Economists’ participation in the evidence-based movement provides the ‘resource’ context into what is primarily a clinical epidemiology exercise (Birch, 2002). Consideration of the impact on both clinical outcomes and health care resources of health care interventions is the basis for the economic evaluation of health care programs. Economic evaluation is concerned with ‘ensuring that the value of what is gained from an activity outweighs the value of what is sacrificed’ (Williams, 1983). The economic question underlying economic evaluation – whether an activity adds more to well-being than the alternative uses of the same resources – would appear to be relevant to health care decision-makers. However, as with the clinical outcomes of interventions, the practice of economic evaluation has tended to approach the estimation of the impact of interventions on both well-being and health care resources in isolation of the problem context. In other words, the practice of economic evaluation has been focused on answering the question ‘Is this intervention an efficient use of health care resources?’ regardless of the context. However, this fails to reflect the underlying nature of the economics discipline and the social science traditions on which it is based.

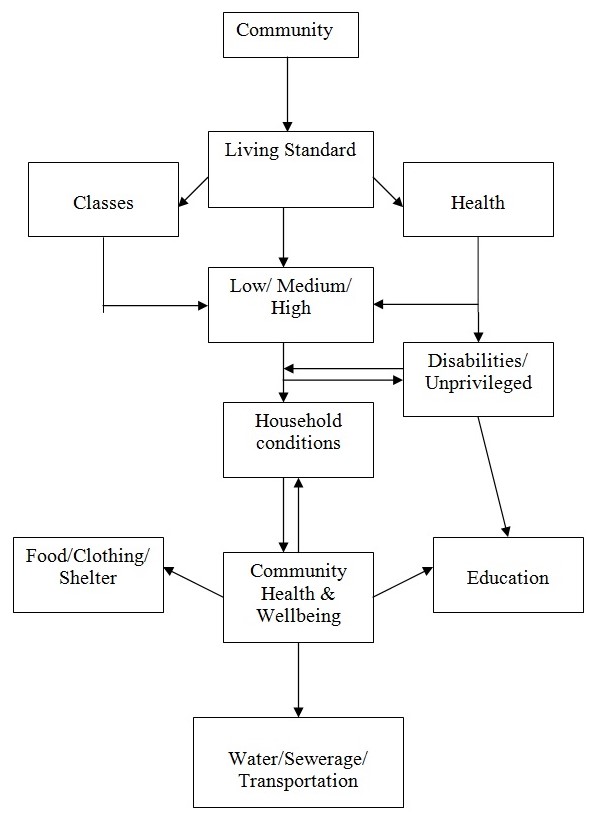

Relationship Diagram between Community and Well being

Conclusion

To make CBI effective we must consider future realization concerning EBM to reconsider the conditions that have always contributed to the growth of the evidence-based approach in clinical settings. We have to think about various aspects of the future growth of our towns and rural areas and in doing so we must not forget the influence of growing economic pressure to control health care costs. Therefore all we can do is the aversion of unnecessary use of services or the use of unproven services which often held out the potential for reducing costs, though the evidence of such an effect is still limited. No doubt that we need strong support to change the conditions of our towns but still a light of hope is there which tells us that a framework for helping decision-makers in community settings assess evidence would be a necessary and important first step toward wider use of evidence in decision making.

References

Amit Vered, (2002) Realizing Community: Concepts, Social Relationships and Sentiments: Routledge: London.

Becker, G. (1965) Theory of the allocation of time, Economic Journal, 75: 493-517.

Birch, S. (2002) “Making the problem fit the solution: evidence-based decision-making and dolly economics, in C. Donaldson, M. Mugford and L. Vale (eds) Evidence-Based Health Economics: From Effectiveness to Efficiency in Systematic Review, London: BMJ Books.

Derose Pitkin Kathryn, Jackson A. Catherine & Kington Raynard, (1998) Evidence-Based Decisionmaking for Community Health Programs: Rand: Santa Monica, CA.

DiCenso, A., Cullum, N. and Ciliska, D. (1998) “Implementing evidence-based nursing: some misconceptions” [Editorial], Evidence-Based Nursing, 1: 38-9. EBN.

Donaldson, C., Mugford, M. and Vale, L. (2002) “Evidence-Based Health Economics: From Effectiveness to Efficiency in Systematic Review”, London: BMJ Books.

Doyle E, Smith CA, Hosokawa MC. (1989) “A process evaluation of a community-based health promotion program for a minority target population” In: Health Education. 20(5): 61-64.

Ehrlich, I. (2000) Uncertain lifetime, life protection and the value of life saving, Journal of Health Economics, 19: 341-67.

Fishbein M. (1996) “Great expectations, or do we ask too much from community-level interventions?” In: Am J Public Health: 86(8):1075-1076.

Greenhalgh, T. (2001) How to Read a Paper: The Basics of Evidence Based Medicine, London: BMJ Books.

Hingson R, McGovern T, Howland J, Heeren T, Winter M, Zakocs R. (1996) “Reducing alcohol-impaired driving in Massachusetts: the Saving Lives Program” In: Am J Public Health. 86(6): 791-797.

Kristiansen Ivar & Mooney Gavin, (2004) Evidence Based Medicine: In Whose Interests?: Routledge: New York.

Laupacis, A., Feeny, D., Detsky, A. and Tugwell, P. (1992) “How attractive does a new technology have to be to warrant adoption and utilization? Tentative guidelines for using clinical and economic evaluation”, Canadian Medical Association Journal, 146: 473-81.

Pappas G, Queen S, Hadden W, Fisher G. “The increasing disparity in mortality between socioeconomic groups in the United States”, 1960 and 1986 In: New England Journal of Medicine. 1993; 329(2):103-109.

Rogers J, Grower R, Supino P. (1992) “Participant evaluation and cost of a community-based health promotion program for elders” In: Public Health Rep. 107(4):417-426.

Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC, Muir Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence-based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. Br Med J. 1996; 312:71-72.

Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC. On the need for evidence-based medicine. J Public Health Medicine. 1995; 17(3):330-334.

Williams, A. (1983) “The economic role of health indicators”, in G. Teeling-Smith (ed.) “Measuring the Social Benefits of Medicine”, London: Office of Health Economics.