Introduction

In an attempt to forecast as well as avoid the development of severe conditions in adulthood, childhood has become a critical element in determining risks. Exposure to abuse, family dysfunction, and neglect when someone is a child have been connected to several physical illnesses and mental issues. The association is believed to result from changes in health-risk behaviors such as increased use of drugs to deal with distress. When one is exposed to much misfortune early in life, it results in poorer health in their future. Various advocates of public health have referred to childhood adversity as a crisis with greater ramifications.

Several states in the United States currently monitor people suffering from different illnesses and check if they experienced any childhood adversity. Proof that connects advanced childhood experiences with an adult’s health comes mainly from research that measures their recollections of their early life. The legitimacy of such a retrospective report has been in question due to likely misclassification or bias. On the one hand, adult respondents may fail to accurately retrieve episodic memory from childhood. On the other hand, they may hide some information about their past as a result of embarrassment. This paper is about a study that seeks to establish the relationship between someone’s childhood and their adulthood health condition.

Methodology

Respondents in this research include members born between April 1972 and March 1973 in New Zealand and were part of the Dunedin study. Their eligibility was based on where they resided in the province and whether they participated in the initial assessment at age three. The cohort depicted a variety of socioeconomic statuses in the general populace of the South Island. Concerning adult health, it matches a survey conducted by the New Zealand National Health and Nutrition with regards to specific indicators, for example, smoking and body mass index. It mainly comprised of White people as less than 7% made up the non-whites, information that is similar to the demographics of the previous investigation.

Assessments were conducted at birth and ages three, five, seven, nine, eleven, thirteen, fifteen, eighteen, twenty-one, twenty-six, thirty-two, and thirty-eight years. The last one was done when the majority of the research members were able to participate. Due to the desire for reproducibility, the examination plan for the paper was posted earlier (Reuben et al., 2016). The researchers obtained consent from the respondents and ensured that the protocol followed was approved by the institutional ethical review boards.

It is important to note that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has articulated an approach to conceptualizing adverse childhood experiences. The researchers’ measure of the ACEs is correspondent to the ten classes of childhood adversity (Berens et al., 2017). They include abuse which can be physical, sexual, or emotional, as well as neglect which could be physical or emotional (Merrick et al., 2017). The other five consist of a family member’s incarceration, household substance abuse, loss of a parent, household psychological disorder, and intimate partner violence. Due to the Dunedin Study starting in the early 70s and the knowledge of the existing since the 90s, the investigation’s definitions of retrospective and prospective adverse childhood experiences were somewhat necessarily varying.

The adverse childhood experiences study gathers retrospectively remembered ACEs through a self-report survey. The researchers’ earlier mentioned measure draws on structured interviews done when the respondents reached adulthood (Briggs et al., 2021). Similar to the investigation conducted by the CDC, they administered the questionnaire at age thirty-eight, which sought to understand the physical, sexual as well as emotional abuse and emotional and physical neglect.

According to the manual, a particular class of harm was present in the event a member of the study had a moderate to severe score. They were interviewed concerning the memories of being exposed to psychological disorders, substance abuse, and incarceration (Sachs‐Ericsson et al., 2017). Some questions were asked to understand whether the environment they grew up in had cases of intimate partner violence. An example includes “…Did you ever see or hear about your mother/father being hit or hurt by your father/mother/stepfather/stepmother?” Losing a parent, either through divorce, separation, or death, was investigated as well.

Results

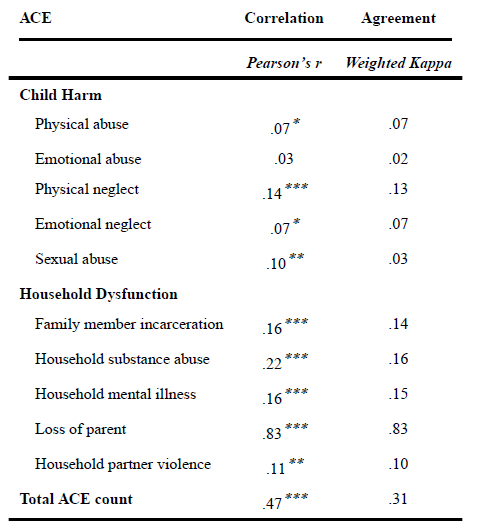

Figure 1 above shows the correlation as well as the agreement coefficients between the scores determined retrospectively and prospectively. At the level of the item, agreement existing amongst retrospectively-remembered and prospectively-documented adversities varied from excellent to poor. At the scale level of total advanced childhood experiences count, the correlation between the scores was r = 0.47, p<0.001, which is a modest impact size (Reuben et al., 2016). Specific agreement between the number of events recalled retrospectively and recorded prospectively was modest. Further examination indicated the overall level of agreement between reports was reliant on the high level of agreement concerning losing a parent. When parental loss was excluded from the ACE measure, the agreement was lower.

In spite of only moderate agreement existing amongst the retrospective and prospective measures of ACE, both were related to the future life outcomes. Effect-sizes for correlation between adult results and prospective advanced childhood experiences were small as well as relatively uniform. Those for association between retrospective past events and outcomes varied more (Reuben et al., 2016). Associations with outcomes measured subjectively had bigger effect-sizes in contrast to those determined objectively. The most significant were for correlations between outcomes of a more mental nature and retrospective childhood negative events.

The researcher utilized multivariate linear regressions to test the associations between retrospective advanced childhood experiences counts as well as adult outcomes whereas regulating for the prospective ACE counts. For the outcomes measured subjectively, retrospective ACEs were still a major predictor even after accounting for prospective ACEs. In comparison, retrospective ACE associations with outcomes established objectively declined to having no significance after addition of controls for prospective ACEs. The trend implied that irrespective of the indications made by the prospective recordings, people’s beliefs that they endured adversity seemed to be greatly associated with the scrutiny of their current life outcomes. The idea that someone went through difficulty in their past did not relate to the outcomes that were measured objectively once consideration was done of the prospective adversities.

In the prospective advanced childhood experiences, sexual abuse may be under-documented. It is thought of as being particularly harmful, as suggested by Reuben et al. (2016). To assess if this could be as a result of biased associations amongst adult outcomes and prospective ACEs, the investigators repeated analyses with sexual abuse eliminated from the count of total retrospective and prospective ACEs. In case false negatives biased the associations with outcomes, the strength of outcome-associations for the two measures needs to become more comparable after removal of sexual abuse from total counts. Then, they as well iteratively detached all types of ACE from the total and did the scrutiny again. The leave-one-out trials failed to alter the outcome which suggested that the overall results were not likely to be biased by wrong categorization in all the components.

The analysis implied that advanced childhood experiences associations with adult outcomes relied on the content recalled from the past. For the outcomes determined objectively, prospectively documented adversity that was not remembered by respondents however forecasted poor outcomes. In comparison, prospectively denoted difficulties that could not be remembered were not associated to adult outcomes established subjectively. This suggests that bias could exist in some people who are viewing their early life in a positive light. Additionally, hardship recalled but recorded prospectively forecasted self-reports of poor memory and health issues unconfirmed by objective tests. Thus, indicating that there are individuals who add some information which was not there since they possess a negative perception.

Conclusion

The paper has been able to establish the relationship between someone’s childhood and their adulthood health condition. It details that exposure to abuse, family dysfunction, and neglect when someone is young has been connected to several physical illnesses and mental issues. It is a belief of experts that the association results from changes in health-risk behaviors such as increased use of drugs to deal with distress. When one is exposed to more misfortunes predicts poorer health. Various advocates of public health have referred to childhood adversity as a crisis with greater ramifications. Several states in the United States currently monitor people suffering from different illnesses and check if they experienced any childhood adversity. Proof that connects ACEs with an adult’s health comes mainly from research that measures their recollections of their early life.

Through the interview method and review of results when participants were younger, the investigators have managed to conduct a thorough research on the issue. In the study, the respondents included members born between April 1972 and March 1973 in New Zealand and were part of the Dunedin study. Their suitability was based on where they resided in the province and whether they participated in the initial assessment at age three. The cohort depicted a variety of socioeconomic status in the general populace of the South Island. Concerning adult health, it matches a survey conducted by the New Zealand National Health and Nutrition with regards to specific indicators, for example, smoking and body mass index. It mainly comprised of White people as less than seven percent made up the non-whites, an information that is similar to the demographics of the previous investigation. The researchers obtained consent from the respondents and ensured that the protocol followed was approved by the institutional ethical review boards. All the results suggested that there is a correlation between a individual’s past and how they live their adulthood especially health-wise.

References

Berens, A. E., Jensen, S. K., & Nelson, C. A. (2017). Biological embedding of childhood adversity: From physiological mechanisms to clinical implications. BMC medicine, 15(1), 1-12. Web.

Briggs, E. C., Amaya-Jackson, L., Putnam, K. T., & Putnam, F. W. (2021). All adverse childhood experiences are not equal: The contribution of synergy to adverse childhood experience scores. American Psychologist, 76(2), 243. Web.

Merrick, M. T., Ports, K. A., Ford, D. C., Afifi, T. O., Gershoff, E. T., & Grogan-Kaylor, A. (2017). Unpacking the impact of adverse childhood experiences on adult mental health.Child abuse & neglect, 69, 10-19. Web.

Reuben, A., Moffitt, T. E., Caspi, A., Belsky, D. W., Harrington, H., Schroeder, F., & Danese, A. (2016). Lest we forget: Comparing retrospective and prospective assessments of adverse childhood experiences in the prediction of adult health. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(10), 1103-1112. Web.

Sachs‐Ericsson, N. J., Sheffler, J. L., Stanley, I. H., Piazza, J. R., & Preacher, K. J. (2017). When emotional pain becomes physical: Adverse childhood experiences, pain, and the role of mood and anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73(10), 1403-1428. Web.