Introduction

African American participation in the creation of American music has affected every genre of music, contributing to the development of a distinctively American sound.

The roots of African-American music may be found in musical genres that developed from the historical situation of slavery that defined African Americans’ lives before the Civil War. Moreover, Their music has contributed to forming the national identity, significantly impacting the lives of millions of Americans by reflecting both the struggles and achievements that black Americans have encountered in the United States.

Music created by black people includes some of the most popular current music genres, including hip-hop, blues, rock and roll, funk, and jazz.

The 1920s

The popularity of African-American blues and jazz grew in the early twentieth century. New performers such as Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, and Chick Webb appeared on urban radio stations, and African-American jazz became increasingly popular.

These performers encouraged young people in the 1920s to rebel against the conventional culture of earlier generations, daring fashion statements, and new radio performances.

During this time of postwar equality and free sexuality, female vocalists like Bessie Smith debuted, paving the path for future female musicians.

Sissle and Eubie Blake’s Shuffle Along marked the return of the black musical to Broadway in the early 1920s.

The 1930s

In the 1930s, full-fledged symphonic compositions based on black cultural themes began to appear. The “Afro-American Symphony” (1931) by William Grant Still made history as the first piece by a black composer to be performed by a symphony orchestra.

Later on, a larger spectrum of Black artists, such as Paul Robeson and Marian Anderson, rose to prominence.

The African American church remained the primary arena for early Gospel music in the 1930s. Minister Charles A. Tindley began to produce and distribute religious hymns written exclusively for his own services, signaling a change.

Mahalia Jackson, whose blues-based vocal style established the gold standard of the genre for decades, was the first gospel artist to be a success beyond the church.

The 1940s-1950s

Rhythm and blues, which first appeared in the 1940s, was a forerunner of rock and roll. The style was acoustically connected to rock & roll, which originated in the 1950s, and was best characterized by Ruth Brown and Louis Jordan.

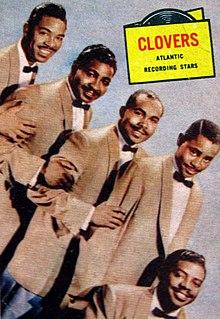

The Cardinals, the Swallows, the Armstrong Four, and the Clovers were all pioneering R&B groups in the 1940s and 1950s. Jam sessions in Harlem clubs like Minton’s Playhouse gave birth to bebop in the 1940s and 1950s. Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Kenny Clarke, and others were among those who jammed at Minton’s.

The big-band sound was the most popular type of jazz in the 1940s. Count Basie’s Big Band, for example, established the standard for what was known as “swing.“

The 1960s

The 1960s began with Hank Ballard and the Midnighters’ release of “The Twist,” a song that became even more popular thanks to Chubby Checker’s interpretation. Twist was popular with the younger generation in the 1960s.

African American music was used to produce uniting anthems for the African American Civil Rights Movement both during and after it.

The evolution of other musical styles was aided by Chicago blues. In the 1960s, bluesmen like Magic Sam, Eddie Floyd, and Ike Turner contributed to the development of genres such as Motown, rhythm and blues, soul, and funk. The Chicago blues of Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, as well as the country blues heritage, were recognized during a folk music renaissance in the 1960s.

The 1970s

In the early 1970s, The Dozens, an urban African-American practice of utilizing fun rhyming mockery, evolved into street jive, which in turn influenced hip-hop. Hip-hop developed among African American communities in places such as New York, Detroit, Chicago, and Los Angeles, shifting long-standing African American cultural styles in new directions.

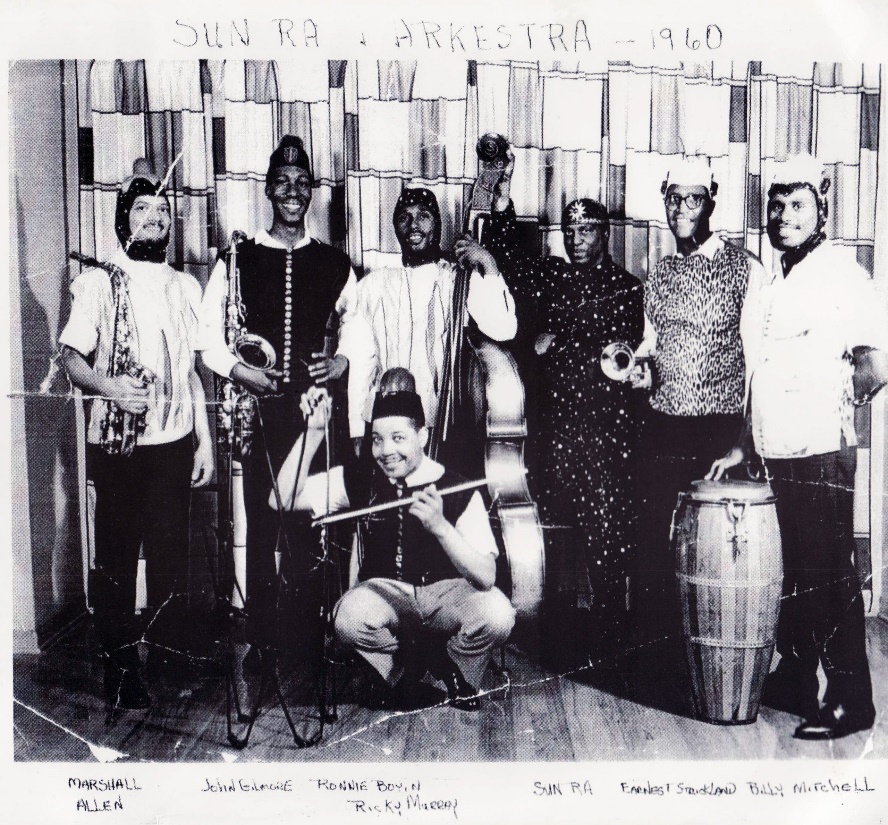

Jazz musicians began experimenting with conventional jazz in the 1970s. The outcome, dubbed “free jazz,” was an approach to creating on bebop’s improvisational and experimental elements. Sun-Ra and his Arkestra, as well as saxophonists Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler, and John Coltrane, were among the free-jazz musicians.

In the early 1970s, the album-oriented soul became hugely popular, changing African-American music. Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder were responsible for the genre’s intellectual and contemplative lyrics.

The 1980s

Michael Jackson’s albums “Off the Wall,” “Bad,” and “Thriller” broke records in the 1980s, changing popular music and paving the way for successful crossover black musicians such as Prince, Lionel Richie, Luther Vandross, Tina Turner, Whitney Houston, and Janet Jackson. By the end of the decade, pop and dance-soul had spawned a new jack swing.

Hip-hop became more diverse as it moved across the country. Techno, dance, Miami bass, post-disco, Chicago house, Los Angeles hardcore, and Washington, D.C. are just a few of the genres represented. During this time, the term “go-go” was coined.

When the rap group Public Enemy debuted in the late 1980s, the political content of rap music made a giant leap forward. The group produced albums with titles like “It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back” and “Fear of a Black Planet.”

The 1990s

Throughout the 1990s, contemporary R&B remained popular. Boyz II Men, TLC, and Destiny’s Child were among the most popular groups in this genre, as were The Temptations and The O’Jays.

“Gangsta rap,” as shown by Ice Cube’s lyrics, was gaining popularity as a means of expressing rage and violence among black adolescents.

During the 1990s, singer-songwriters like R. Kelly, D’Angelo, and Aaliyah were hugely successful, and singers like Mary J. Blige, Faith Evans, and BLACKstreet promoted a fusion style known as hip-hop soul.

D’Angelo, Erykah Badu, Maxwell, Alicia Keys, Jill Scott, Angie Stone, Bilal, and Musiq Soulchild popularized the neo-soul trend of the 1990s, which leaned back on more classical soul inspirations.

References

“African American Song.” The Library of Congress, 2015. Web.

Ramsey, Guthrie P. “African American Music.” Oxford Music Online. 2016. Web.

The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. “Pop Music and the Spatialization of Race in the 1990s.”. 2012. Web.

“The History of African American Music.” Encyclopedia. 2014. Web.