Agricultural Geography

Agricultural geography is a subdivision of geography that focuses on cultivated areas and the impact of farming on the physical landscape (Grigg 4). To be precise, it is a branch of economic geography that deals with the territorial distribution of cultivated lands and the factors that influence the distribution (Husain 3).

The distinct territorial distribution of cultivated land is based on the relationship between agriculture and the natural environment. The locations spread of areas of cultivated land adheres to several legislations characteristics of the socioeconomic structures of the locality (Grigg 5).

The impact of the disparity in the natural environment which causes variable conditions in different geographical areas is reflected in the productivity, production cost and efficiency of production (Husain 9). However, the relationship of these indicators in different regions cannot be regarded as a mere manifestation of the disparity in the natural conditions. This is because the crop development may be considerably altered through land reclamation and cropping method used (Morris, Trisalyn, and Aleck, 4).

Therefore, the disparity in environmental conditions calls for different methods of farming. The most significant elements of agricultural geography entail mapping and modelling of various types of land use and organization of land used by different enterprises (Morris, Trisalyn, and Aleck, 4). The aim of this study is to explore agricultural geography and the production and consumption of food in British Columbia.

Agricultural Geography in British Columbia

British Columbia is a province in western Canada. It is home to a number of the most inventive and advanced food policy in North America (Morrison 4). British Columbia is the second largest province in terms of land area. The province is characterized by high mountains and plateaus. More than half of its land is 1000m above sea level and almost a quarter is rocky and covered with Ice.

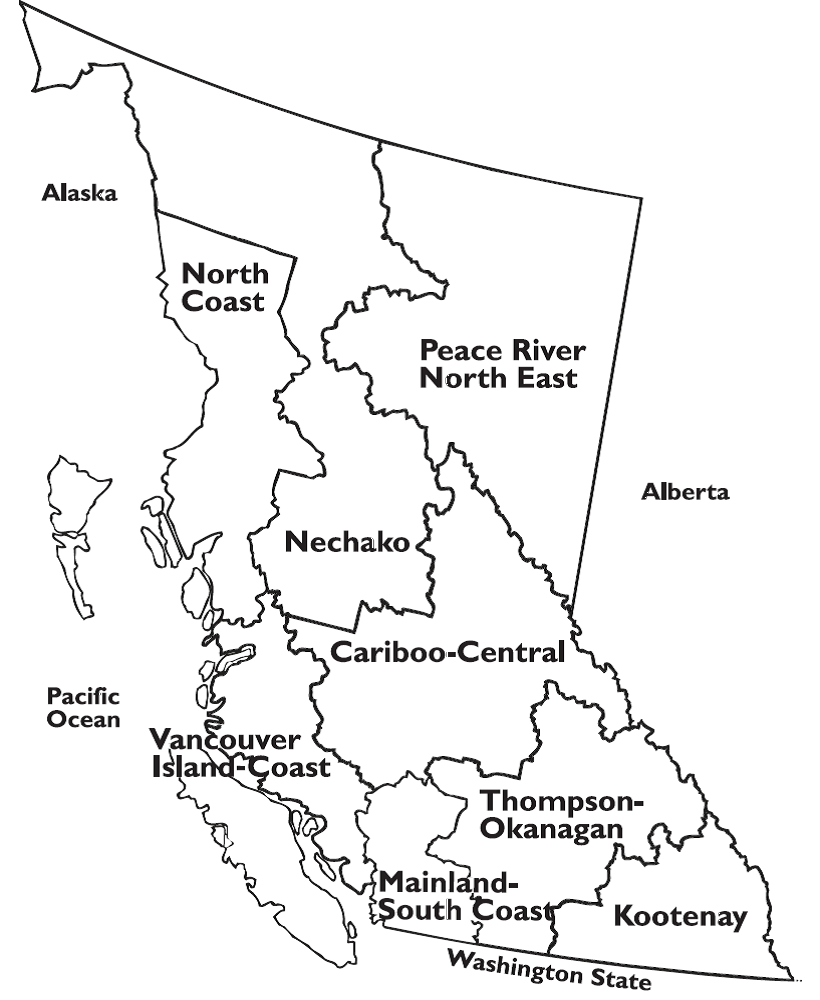

The nature of the physical landscape of British Columbia has led to the scarcity of agricultural land. Less than 3 percent of the province is agriculturally viable (Curran. 8) However, the 2008 agricultural census indicates the high quality of the agricultural land and intensity of land use in British Columbia. The province accounted for more than ten percent of the Canadian agricultural output in that year (Ministry of Agriculture and Lands 10). The figure below shows a map of the agricultural regions of British Columbia.

Source: (Ministry of Agriculture and Lands 10).

The Agricultural Land Reserve (ALR) is the policy used to protect agricultural land from other forms of development (Androkovich, Desjardins and Tarzwell 6). The regional health authorities in the province are developing and implementing policies that are basically promoting the production and consumption of local foods (Provincial Health Services Authority 12).

The interest in local food grew tremendously over the last ten years due to environmental sustainability concerns, farming and food security (Act Now BC 1). A number of food security experts believe that production of local food is the answer to food security in the Province (BC Ministry of Agriculture and Lands 3).

In 2012, the province had approximately 19800 farms covering 2.8 million hectares. Of this, 0.586 million hectares were in crops and 1.7 hectares were grazing land. Out of 10 hectares, 8.5 million hectares were crowned lands used by the ranching sector (Ministry of Agriculture and Lands 5).

The arable soils in the province are mapped and categorized on quality basis ranging from class one to seven. Class one soils are the best and the most appropriate while class seven is the least appropriate. The best arable soils in the province are placed under ALR and are strictly preserved agricultural purpose. Approximately 5 million hectares of land fall under the best arable soils (Curran 9).

During 2010, an average farm was estimated to be 140 hectares. However, the farm size significantly depended on activity type, from ten of thousands hectares for ranching business to less than a hectare for a poultry enterprise (BC Ministry of Agriculture and Lands 22). Agriculture in the province is differentiated by its miscellany.

Some of the agricultural activities carried out in the province include dairy husbandry, cattle ranching, and poultry production in addition to horticultural farming. Agriculture is the third largest economic activity after forestry and mining (BC Ministry of Agriculture and Lands 22).

The principal component of the agricultural sector, in terms of capital and income, is livestock (mainly dairy) and related products. Other livestock enterprises include beef and poultry production. The dairy industry is found mainly in the lower mainland, southeast Vancouver and the North Okanagan (Ministry of Agriculture and Lands 3).

Cattle ranches are concentrated in the southern and central region, north-eastern region, and the Kootenays. On the other hand, beef production is carried out all over the province at large and small scale. Swine and poultry farming are concentrated around Vancouver and Victoria, though highly populated areas also carry out swine and poultry production (Ministry of Agriculture and Lands 4).

The most significant crops in British Columbia include floriculture, garden crops, berries and grapes, and tree fruits. Tree fruits and grapes are grown in the southern interior. The lower Fraser Valley and Southern Vancouver Island, characterized by cool and wet climate, are the most appropriate for berries and vegetable growing. Most of the horticultural and floricultural crops are grown in the fertile soils and even terrains of the Fraser River Delta.

Soils in the Fraser River Delta are among the richest in the whole Canada. Over 95 percent of the greenhouses are found in this region. Most of the cereals in the province are produced in the Peace River basin and the Kootenay region. The North Eastern Peace River area has a prairie like terrain which is suitable for the growth of oil seeds and grains given its physical landscape and climate (Androkovich, Desjardins and Tarzwell 6; Ministry of Agriculture and Lands 4).

Aquaculture is also an integral part of farming in British Columbia (FSDS 2). The most common fish species in the fish farms are finfish (almost exclusively salmon), shellfish (oysters, mussels, scallops and geoducks) and planktons. Fish farming in British Columbia involves three distinct processes: fish hatcheries, fish ponds and recreational trout fee-fishing farms (Fisheries and Oceans Canada 3).

Besides meeting the ever-growing demand for fresh, wholesome and steadfast supply of protein, British Columbian aquaculture also produces a range of non-food products used in aesthetic, fabric, pharmaceutical and biotechnological sector (Gayton 8).

The province has four types of aquaculture namely: marine finfish, shellfish, and freshwater finfish and enrichment facilities (Fast Stats 7). Marine finfish ponds are found in about 135 sites mainly located in Port Hardy, Tofino and Campbell River. Fresh water finfish and shellfish are found in approximately 80 and 500 sites respectively spread across the province. The aim of enhancing facilities is to replenish the dwindling wild fish stocks (Fisheries and Oceans Canada 4).

Major Impact of Agricultural activities on the landscape

A number of studies have been carried out to evaluate the impact of agricultural activities on the environment. These activities include the cultivation of field crops, horticultural crops, vineyards, fruit trees, and livestock ranching and zero grazing (Gayton 22). The impact includes loss of habitat and land fragmentation, pollution from agrichemicals and animal wastes, overgrazing and destruction of local plant communities, and the spread of harmful weeds (Gayton 23).

Numerous efforts have been made to weigh up the impact of ranching on the crown lands (Ministry of Agriculture and Lands 15). The biggest of these initiatives was the Ministry of Agriculture’s Rangeland Reference Location Programs. The study assessed the impact of ranching on native vegetation using temporary and permanent enclosures.

The study established that ranching destroys native plant communities, natural habitats for wildlife, extirpation of riparian vegetation as well as interference with soil structure exposing soil to the dangers of soil erosion. Poorly managed ranches experienced scenarios where the soil was left bare with zero vegetation cover (Ministry of Agriculture and Lands 16).

Excessive use of Agrochemicals especially in the horticultural and crop farms has led to contamination and subsequent eutrophication of local rivers and other water bodies. Pollution and ensuing eutrophication of the surface waters is the principal constituent of agriculture’s negative effect on biodiversity (Gayton 23). The negative impact of Agrochemicals on the local environment forced the Fraser Basin Council to come up with a plan to safeguard Fraser River (Curan 19).

Due to its strategic location ecologically, the production of grapes has had considerable impact on the local environment (Feagan 24). For instance, antelopes in the South Okanagan are in great danger due to the expansion of grape farms. The high demand for wine has led to the expansion of orchards and wanton deforestation. This means that the antelope habitat is growing thin and thinner (Feagan 24).

Food production and Consumption

The term ‘food self sufficiency’ has dominated food security debates over the recent past (Feenstra 28). Food self sufficiency describes the amount of food produced and consumed locally and what needs to be done to provide enough food for the ever-growing population (Wesche and Henry 2).

Food self sufficiency also includes affordability of food (Hinrichs 35). The population of British Colombia stood at about 4.41 million in 2011 census. The figure is expected to rise by 30% by 2025 (Statistics Canada 2). Sustainable development experts in British Columbia have started to include food in their sustainability plan (Morrison 4).

The local farmers produce about 48% (approximately 1600 million kilograms) of the food consumed in British Columbia. The local consumption is about 3300 million kilograms. The shortfall is met by importing food from other provinces and outside the country (Ministry of Agriculture 3). However, the province is 159% (300 million kilograms produced compared to 180 million kilograms consumed) self reliant in the production of fruits. Therefore, it can meet the local demand and export the surplus (Ministry of Agriculture 4).

The province also shows slightly higher figures in dairy and beef products (Statistics Canada 4). Dairy and beef products are 57% and 64% respectively in terms of self reliance. The aggregate dairy production stands at about 620 million kilograms compared to the local consumption of 1100 million kilograms. Similarly, beef production stands at 300 million kilograms compared to 470 million kilograms consumed in the province (Ministry of Agriculture 6). Grains are the least produced foodstuff and the province 14% self reliant.

Grain production stands at about 45 million kilograms compared to 319 kilograms consumed. Vegetables produced are approximately 335 million kilograms compared to 765 million kilograms consumed. In other words, the province is 43% self reliant in terms of vegetables. Last but not least, the province is 472% self reliant in the production of fish. The aquaculture production is estimated to about 182 million kilograms compared to 41 million kilograms consumed (Ministry of Agriculture 7).

British Columbia is a peculiar province where the citizens are highly involved in the production and consumption of local food for health and dietary reasons (Vancouver Food Policy Council 45; Act Now BC 1). Food consumption estimates in the province also varies according to age and gender groups (Ostry 11). British Columbia’s health and nutrition reports show that Adult males between the ages of 18 to 44 consume 50 percent more food than females except for fruits and vegetables which is 30 percent more (Ostry 12).

Almost half of the foods eaten by the youths are dairy products compared to one third by adults. Adult females have a tendency to eat extra fruits and vegetables and less amount of meat and grains compared to their male counterparts. Females tend to consume almost the same amount of food throughout their lifetime. On the other hand, male food consumption drops with age advancement (Ostry 13).

Works Cited

Androkovich, Robert, Ivan Desjardins, and Tarzwell, Gordon . “Land preservation in British Columbia: An empirical analysis of the factors underlying public support and willingness to pay.” Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics 4.3 (2008): 5-50. Print.

Act Now BC. “Healthy Eating.” Healthy Living Tip. Act Now BC, 2006. Web.

BC Ministry of Agriculture and Lands. The British Columbia Agriculture Plan: Producing Local Food in a Changing World. British Columbia: Government of British Columbia, 2010.Print.

Curran, Deborah. Protecting the Working Landscape of Agriculture. British Columbia: The Law Foundation of British Columbia, 2005. Print.

Fast Stats. Agriculture, Aquaculture and Food. British Columbia: Ministry of Agriculture. 2010. Print.

Feenstra, G. (1997). “Local food systems and sustainable communities.” American Journal of Alternative Agriculture 12.1: 28-36. Print.

Feagan, Robert. “The place of food: mapping out the ‘local’ in local food systems.” Progress in Human Geography 31.1 (2007): 23-42. Print.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Aquaculture in British Columbia. Vancouver: DFO, 2010. Print.

FSDS. Aquaculture in Canada: The Aquaculture Sustainability Reporting Initiative. Ontario: Federal Sustainability Development, 2010. Print.

Gayton, Don. “Major Impacts To Biodiversity In British Columbia”. A Report To The Conservation Planning Tools Committee. 2007: 1-25. Print.

Grigg, David. An Introduction to Agricultural Geography. London: Routledge, 1995. Print.

Hinrichs, Clare. “The practice and politics of food system localization.” Journal of Rural Studies 19. 1 (2003): 33-45. Print.

Husain, Majid. Agricultural Geography. Delhi: Inter-India Publications, 1979. Print.

Ministry of Agriculture. Grow BC: a Guide to BC’s Agricultural Resources. Abbotsford, British Columbia: National Library of Canada. 2008. Print.

Ministry of Agriculture and Lands. B.C. Food Self Reliance Report. Government of British Columbia. Vancouver: CCHS, 2012. Print.

Morrison, Kathryn. Mapping and Modelling British Columbia’s Food Self Sufficiency. Victoria: University of Victoria. 2011. Print.

Morrison, Kathryn, Trisalyn, Nelson, and Aleck, Ostry. ‘Mapping Spatial Variation in Food Consumption’. Applied Geography 31(2011): 1262-1267.Print.

Ostry, Aleck. Nutrition Policy in Canada, 1870-1939. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2006. Print.

Provincial Health Services Authority. Implementing Food Security Indicators: Food Security Indicators Project Phase II. Vancouver: The Government of British Columbia, 2010.Print.

Statistics Canada. Farm data and farm operator data tables, 2009. Web.

Vancouver Food Policy Council. Food Secure Vancouver: Baseline Report. Vancouver, 2009: 1-81.Print.

Wesche, Sonia, and Henry, Chan. “Adapting to the Impacts of Climate Change on Food Security among Inuit in the Western Canadian Arctic”. Journal of Economy and Health 1 (2010): 1-13. Print.