Introduction

The ideas associated with the construction of an ideal city were a vital part of architecture until the 21st century. It is not surprising that the rulers of many countries were concerned with the role of architecture, especially those in which the dictatorship and authority of one person were manifested. As the representative of Nazism and totalitarianism, Hitler strived for order, universal correctness, and validity, working on the idea of some utopian town-planning project.

In the center of attention of Hitler, there was the restructuring of Berlin by the architect Albert Speer. Such buildings as the Volkshalle and the Cathedral of Light were the most expressive projects that illustrated the power and authority of the Nazi regime. To understand the role of the architectural Nazi propaganda in an in-depth manner, this paper will discuss the works of Speer, both internal and external scales, including their inherent aims and perception by people.

Albert Speers’ Works

Architecture and Nazi Germany

A supporter of classicism, Hitler admired the layout of the center of Paris and especially that of Vienna. In his memoirs, Speer mentioned the words of Hitler, who stated that Berlin is a large city, but not a world city; it is nothing more than a disorderly cluster of buildings, and it is necessary to surpass Paris and Vienna. The Third Reich could not exist without the support of representatives of various spheres – not only military and political but also economic, social, and cultural ones. Albert Speer was an architect by profession. Nevertheless, he managed to become one of the most influential figures in Nazi Germany and Hitler’s confidant.

At the Congress of the party in Nuremberg, the cultural program of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) was adopted. In particular, it declared that since Germany should consider the eternity of the Empire, works of art were also to become eternal, thus satisfying not only the magnificence of their concept but also the clarity of the plan along with harmony of their relations. These powerful works were also to be an exalted excuse for the political strength of the German nation. It should be emphasized that the above statement concerned primarily architecture.

Role of Urban Scale-Relationship with the City in Implementing Nazi Policies

Albert Speer developed a project of the so-called new Berlin architecture, which was supposed to be implemented by 1950. According to the mentioned project, several railway stations, a town hall, a soldier’s palace, an opera house, and the Reich’s chancery were to be located on the main axis of the capital. The General Construction Inspectorate led by Speer began with the compilation of lists of Berlin Jews subject to eviction from the city.

Many of them owned luxury apartments in good houses, which the Reich planned to use for their purposes. By the way, the office headed by Speer was also engaged in the construction of concentration camps. In 1942, Hitler appointed Speer to the post of Reich Minister of Armaments and War Production. He managed to significantly increase the productivity of military-industrial enterprises through the involvement of forced labor of prisoners and those of concentration camps.

On the avenue located north-south, there was a plan to erect a Triumphal Arch with a height of 117 meters and a width of 170 meters. On the construction, Hitler wanted to carve the name of every German soldier who died in World War I. The image of the arch turned out to be extremely cumbersome, but Hitler did not allow Speer to ease it, and the arch and a wide avenue were built. The rest of the layout of Berlin was background: Hitler was not interested in either the purpose of the buildings or the effectiveness of the grid of streets. He was not worried that the implementation of the project required massive destruction in Berlin.

Nevertheless, he understood that if the stratospheric rates of the project cost became known to the general public, the project might be unpopular. Therefore, the financing of the project was divided between different departments. At the end of the war, Speer without notifying Hitler spent the fund for humanitarian needs collected for construction.

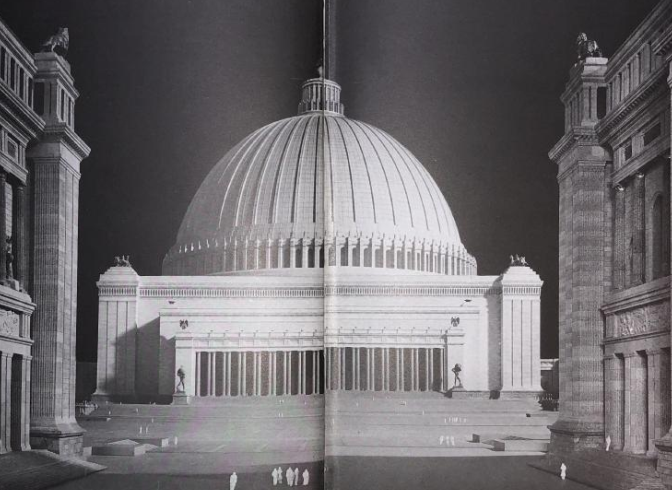

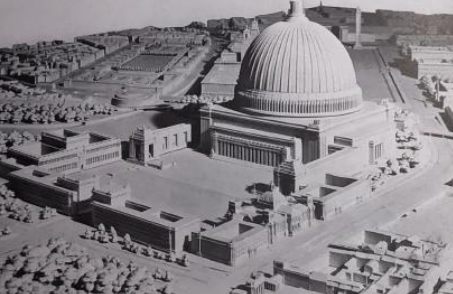

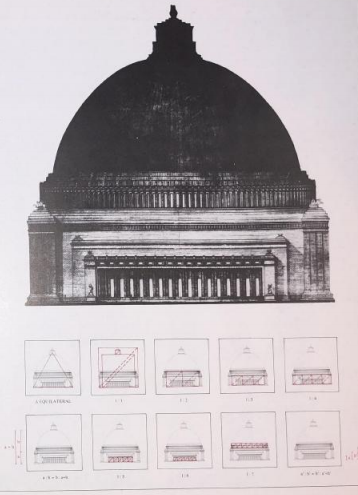

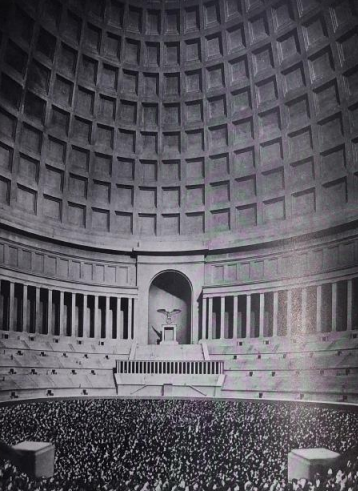

Hitler continued to focus mainly on palaces, museums, theaters, ministries, and other important buildings. The Volkshalle, the People’s Hall, which is the main building of the Reich, was intended to be a 300-meter diameter dome and equip it with a hall with a capacity of 150-180 thousand people. Its height was 320 meters with a perimeter of 315 × 315. The Volkshalle is perceived as a colossal dome building, monstrous and great at the same time (see Picture 1).

Speer subsequently noted why Hitler insisted on such large dimensions. The Ulm Cathedral, for example, had an area of 2500 square meters. The very idea of designing such a building may be interpreted as the intentions of superiority over other nations and elevation of the Nazi regime. In other words, the building seems to be conceived as the one to demonstrate the power and potential of Hitler, while paranoiac architectural monumentalism can also be noted. In particular, disproportionate forms in terms of other buildings and the whole city look like the expressions of personality disorder. Compared to Newton’s Cenotaph that also relates to monumentalism, the Volkshalle intends to affect human consciousness and subjugate it in a sense.

A grandiose and magnificent picture unfolds before the viewers while they look at the Volkshalle. The presentation of the building is expressive and poetic. At the same time, gigantic dimensions of the construction do not deny grace. The idea of the Volkshalle was designed to impress the human imagination since the upwardly directed building was to reflect the greatness of the Nazi leader. Since Hitler was personally overseeing developments in the field of Nazi architecture, one may suggest that he understood its role in building and promoting his Nazi ideas to people.

Megalomania along with an imprint of the neo-classical motives can be traced in the forms of the People’s Hall likewise in the Cenotaph of Newton. However, the paramount task of presenting monstrously huge and impressive projects of Hitler was realized through the mentioned building to result in reverential awe and cause a mobilizing effect that was rather important for the Nazis. Not shelters or houses, but powerful and large-scale buildings likewise were declared as signs of a new culture of Nazism.

Likewise other works of totalitarian art, the above building was called not only to admire but also to terrify, not without reason it resembles monstrous giants. The People’s Hall was to correspond to the idea of the sublime in the understanding of Kant and Burke. Kant distinguishes between two varieties of the sublime – mathematical and dynamic, and the former may be viewed drawing on the example of the People’s Hall.

One gets the impression that what he or she sees goes far beyond his or her sensory perception, and people tend to imagine more than is available to their eyes. As clarified by Kant, a person is inclined to this because his or her mind (the ability to comprehend the ideas of God or the world or freedom that cannot embrace intellect) tells to postulate an infinite that cannot be felt by senses and imagination to be embraced in a single intuitive image. Instead, the Volkshalle translates a restless and negative pleasure that allows people to feel the greatness of subjectivity capable of wanting something inaccessible.

In his turn, Burke’s ideas also found their embodiment in the representation of the Volkshalle. The mentioned philosopher considered fear and suffering as the emotional sources of the sublime, while objects themselves include emotional esthetics. In the philosophical and aesthetic views of Burke, the combination of analysis of a person’s thinking abilities and his or her reactions to the experienced pleasure, affectation, and manifestation of the morals and actions of other people are traced. Being derived from displeasure or danger, these emotions, far outweigh all the other effects of power and are primarily connected with the experience of the sublime.

In the Volkshalle, fear causes the dominant principle of the sublime, and the latter may be characterized as the strongest emotion that the soul is capable of experiencing. Consistent with the philosophy of Burke, the reasons for such a strong and deep perception of the People’s Hall are rather impressive factors such as strength, power, megalomania, infinity, and the subsequently occurred magnificence.

The concept of haunted buildings elaborated by Vidler may also be noted in terms of the Volkshalle and margins of the sublime. The genre of uncanny in architecture reveals the essence of its very idea. In particular, unattainability is emphasized by the author as the core root of a pathological uncanny world within the boundaries of fear. An unattainable ideal of conquering other nations, implanting new perverse culture, and Hitler’s personality striving for enormous power and terror help to understand the aim of the People’s Hall.

The architecture of the People’s Hall building was permeated with the idea of going beyond the limits of the human, which connects with the figure of the totalitarian leader – Hitler. It seems that all this sublime symbolism was designed to reflect his greatness as he wanted to see the architecture of his time, and on these principles, he began to rebuild Berlin and other German cities. The Reich Chancellor proclaimed the following requirements for architecture: there should be no native places and chamber buildings, but the majestic figures adopted from the time of Egypt and Babylon should be adjusted.

Nazi architecture should create sacred structures as iconic symbols of new high culture. Using the above symbolism, Hitler was to evoke the inexhaustible spiritual nature of people and the time. The comfort was to be denied as a great man should live in a magnificent building.

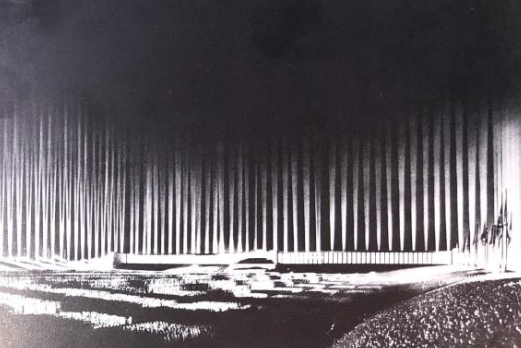

Solemn events such as NSDAP parties took place at the Arena of Luitpold, a square located on the outskirts of the city, which could hold up to 150,000 people, as well as in the Hall of Luitpold, the capacity of which was 16,000 people. Since 1933, festive events stretched for eight days, and there was also an impressive light show in the program of late congresses called the Cathedral of Light. Albert Speer used 150 antiaircraft searchlights to create the above building (see Picture 5).

As a replacement for the unfinished stadium, Speer created the Cathedral that was built not of concrete but light. The architect borrowed from the Luftwaffe powerful antiaircraft searchlights and sent them skyward at intervals of 12 meters. When the installation was switched on at night, it created a huge wall of high rays. They surrounded the site and made it visible for tens of kilometers around.

Speer described the effect of the Cathedral of Light as being in a vast room with mighty pillars of light instead of concrete outer walls. The German stadium was added to the list of famous unfinished buildings as it was never completed. These rays were grandiose propaganda events carefully organized to strengthen Nazi Party’s enthusiasm and demonstrate the power of National Socialism to the whole world.

Sometimes, a cloud floated through this luminous crown, becoming surrealist elements in the already fantastic spectacle. It seems that the Cathedral of Light was the first example of a luminescent architecture, and it remains to this day not only the embodiment of the most beautiful architectural concept but also the only creation that survived its epoch and stood the test of time. This building remains solemn and beautiful. Largely due to the work of Speer in the first half of the 30s, Hitler attracted the greater part of Germany unaware that Hitler would start burning people in the stoves in a few years and would drag the country into the most terrible war in history.

Importance of Residential Architecture and Interior as an Essential Element of Nazi Architectural Propaganda

Along with the huge buildings that were discussed above, it is significant to note the second direction – the residential architecture. Unlike Stalin, Hitler not only did not stop but also strengthened the construction of houses for workers, for which a traditional folk style with pitched roofs was prescribed. The contemporary style with flat roofs and horizontal windows characteristic to the given period was banned. The single-family houses of Nazi time were not fundamentally different from the interlocked houses of Ernst Mayor Bruno Taut (see Pictures 6 and 7). The point is that the principles of rationalism were embodied in the works of the above architects.

In Nazi Germany, such houses became a special direction and an effective tool of propaganda: the monumental majestic structures, according to Hitler’s plan, we’re supposed to suppress the size and the greatness of the enemies of Germany, and also cause awe in people. The grandiose architecture of the Third Reich should have been better than others to demonstrate the superiority of the regime and glorify the power of the Aryan race.

As Speer noted, several Washington Capitolions could be placed in such a building as People’s Hall. Inside, the hall was designed for 180 thousand people. The dome of the building was crowned by the German eagle, holding the globe in its hands. Nearby, there stretched a pool of 1200 × 400 meters, the largest in the world. Here, Hitler was to meet with people on an annual basis. The vast dome was expected to act as a symbol of the roof over the “center of the world.”

Goals Pursued by Hitler and Speer in Architecture

Nazi art, especially architecture, should have continued a clear hierarchical line, which involved three pivotal elements that are as follows: ideology, a leader, and a nation. In combination, these three components constituted a mythological time continuum. A leader in a totalitarian society was the embodiment of the perfect representative of a new formation and personified the happy and ideal future.

The task of the Nazi Party was to unite the present and the future. In this regard, Hitler used the Communists’ experience in organizing open mass meetings, while taking the religious ritual of the Catholic Church as a model, copying the pomposity of Kaiser’s time. The spirituality of the masses was considered by Hitler in the true sense of the word along with the gigantic revival of the aspirations of the German people.

Art seemed to him, therefore, a political tool. He believed that national-socialist holidays should be solemn, they should not only demand national unity but also strengthen the authority of the idea. In the very organization of the Nazi movement, Hitler saw a certain theatrical nature, which embodied politics and art almost exclusively through large and spectacular dramatizations and which was animated through them.

Likewise, a theatrical production needs a stage in the broadest sense of the word, people need holidays and mass events in terms of architectural framing. From all that has been said, it follows that Hitler actively patronized architecture not so much from his structural position as a sovereign leader, seeking to win himself popularity as patronage, but from personal attachment, being keen on this type of art. However, since he was, above all, a politician and head of a totalitarian state, he inevitably embodied in his architectural ideas and all his architectural creativity the same totalitarian ideas clothed in stone.

Looking at the mentioned buildings, people experienced overwhelm and admiration targeted by Hitler as well as deceit aimed at replacing peaceful intentions with the desire to be above others. The pathological megalomania that is observed in the works of Speer illustrates grandeur and monumentality called to preserve the Nazi regime for eternity. More to the point, Speer’s oeuvre emphasized the authority of Hitler and strived to imprint his image for centuries.

There is no coincidence that Hitler saw the embodiment of the eternity and grandeur of old eras and people in architecture, contrasting it with other more dynamic and quickly disappearing elements of culture. Thus, the idea of greatness and immortality became the core of the architecture of the Nazi time. Formally, this was achieved by the following methods: sharp enlargement of buildings; creation of a clear rhythm of simple architectural forms (towers, columns, blocks, arches, etc.); and the formation of wide-open spaces, limited by architectural wings (fields, stadiums, etc.) (see Pictures 3, 4, and 5).

A return to the architectural forms of the classicism of the nineteenth century was accompanied by easy visibility, clarity, and simplicity of architectural compositions. Looking back in his memoirs, Albert Speer saw in the architecture of the Third Reich, which he created among others, cruelty and the exact expression of tyranny. This late and undoubtedly self-critical assessment was emotional but quite accurately reflected architectonics of megalomania projects of Nazi time designed to suppress a person, inspire him or her with awe and reverence for the daring power of the great Nazi leader as well as the idea of selfless service to the state through the dissolution of the person in the public.

The architecture of Nazism inherits antiquity and renaissance, yet it reinterprets and simplifies the classics: modest cornices and columns are often devoid of capitals. Hitler’s preferences are gigantomastia and aspiration for the past made the Nazi propaganda to be based on German functionalism, adding to it the scale and power. Berlin for Hitler, like Moscow for Stalin, was the future capital of the world. However, the architectural heritage is not limited to the ancient heritage, the aesthetics and symbolism of the Eastern despotism were also rather close to the totalitarian culture.

Speer’s works and the ambition of Hitler to create something eternal may be considered from a different angle. As perpetual objects imply an ever-lasting representation of their ideas, the People’s Hall and other buildings cannot be regarded as eternal. Today, they are perceived by people as the exclusive heritage of Nazi terror and horrific events. The Nazi constructions were to symbolize power expressed in static stone massifs, which were practically devoid of ornamental décor and refer to the Egyptian and Sumerian temple architecture. There is no visible and tangible embodiment of these architectural monuments that can stand for millennia. In this regard, the buildings of the Third Reich can hardly be marked as eternal ones.

Conclusion

To conclude, it was discovered that Nazi architecture was primarily based on the intention to reflect the power and greatness of Hitler. The notion of sublime caused by unattainability and fear was specified as the key explanation of Nazi architectural ideas. At the same time, Hitler’s madness and ambitions as well as striving for eternity in architecture were not achieved since he failed to win the war and now is perceived merely as a paranoiac Nazi leader. The orientation to eternity was embodied in the idea of such buildings as the People’s Hall and the Cathedral of Light. The mentioned architecture was called to evoke the feelings of awe, greatness, and power inherited in Hitler and Nazi propaganda. The two paramount goals of the latter were to admire and encourage people to support their leader and also to terrify other countries and cultures.

Bibliography

Antoszczyszyn, Marek. “Manipulations of Architecture of Power; German New Reichschancellery in Berlin 1938-1939 by Albert Speer.” Technical Issues 3 (2016): 3-12.

Fest, Joachim C. Albert Speer: Conversations with Hitler’s Architect. Cambridge: Polity, 2007.

Hagen, Joshua, and Robert Ostergren. “Spectacle, Architecture and Place at the Nuremberg Party Rallies: Projecting a Nazi Vision of Past, Present and Future.” Cultural Geographies 13, no. 2 (2006): 157-181.

Hirshberg, Gur. “Burke, Kant and the Sublime.” Philosophy Now 11, (1994): 17-20.

Krier, Leon. Albert Speer: Architecture, 1932-1942. New York: Monacelli Press, 2013.

Nelis, Jan. “Modernist Neo‐Classicism and Antiquity in the Political Religion of Nazism: Adolf Hitler as Poietes of the Third Reich.” Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions 9, no. 4 (2008): 475-490.

Sereny, Gitta. Albert Speer: His Battle with Truth. London: Pan Macmillan, 2017.

Speer, Albert. Inside the Third Reich. London: Hachette UK, 2015.

Stuart, Charlotte L. “Architecture in Nazi Germany: A Rhetorical Perspective.” Western Speech 37, no. 4 (1973): 253-263.

Taylor, Blaine. Hitler’s Engineers: Fritz Todt and Albert Speer-Master Builders of the Third Reich. Philadelphia: Casemate, 2010.

Thies, Jochen. Hitler’s Plans for Global Domination: Nazi Architecture and Ultimate War Aims. New York: Berghahn Books, 2012.

Vidler, Anthony. “The Architecture of the Uncanny: The Unhomely Houses of the Romantic Sublime.” Assemblage 3, (1987): 6-29.

Appendices