Introduction

E-commerce is a powerful force in global business that has completely transformed the way goods are being purchased around the world. In addition to changing the structure of modern business operations, e-commerce, as well as the ever-evolving information technology (IT) that precipitated its emergence, has completely transformed logistics (Bowersox et al. 2013; Qin et al. 2014).

Modern business to consumer companies (B2Cs) must have seamless coordination between their e-commerce activities and logistics in order to gain and retain a competitive edge in the business environment characterized by a high level of rivalry. In fact, if an e-commerce company is not capable of delivering goods on time, its customers will opt either for a traditional shopping environment (brick and mortar stores) or will turn to its competitors. Therefore, without the support of effective logistics, it is impossible to imagine a viable e-commerce model.

The aim of this paper is to analyze the logistics operations of the largest e-commerce company in the world and identify several areas for improvement. The paper will focus on the following areas of Amazon’s logistics operations: inventory, transportation, packaging, handling, and warehousing. It will also provide recommendations for minimizing logistics costs and improving the logistical value proposition.

Overview of the Company

Amazon.com, Inc. (henceforth Amazon) is an e-commerce company based in Seattle that dominates the market of Internet shopping. The company was established in 1994 and became the largest retailer in the world whose revenue surpassed $61 billion in 2012 (Taniguchi & Thompson 2015). The tech giant continuously expands its overseas presence and, currently, it holds dominant positions in the UK, the US, Australia, Japan, China, India, Mexico, and many European countries among others. Amazon operates multiple websites and has more than 40 subsidiaries around the globe (Amazon n.d.).

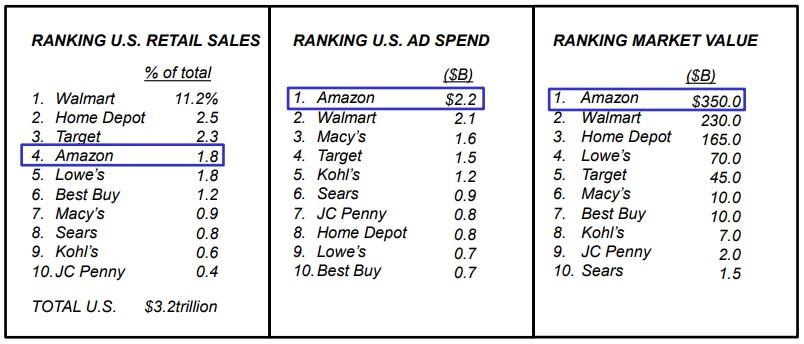

The retailing powerhouse specializes in selling numerous products and services that include, but are not limited to, books, apparel, consumer electronics, food, groceries, tools, musical instruments, and software. Also, a company’s recent announcement to acquire Whole Foods Market in a $13.4 billion deal shows its intention to challenge a multinational retailing corporation Walmart by becoming a major player in grocery retail (Goldman 2017; Wingfield & Merced 2017). Figure 1 shows the company’s rankings in US retail sales, advertising spending, and market value.

Amazon Logistics

Before starting the overview of the company’s logistics operations, it is important to formulate a precise and comprehensive definition of the term ‘logistics.’ According to Richardson, Castree, and Marston (2017, p. 143), logistics refers to “the process of planning, implementing, and controlling the efficient, cost-effective, and synchronized flow and storage of raw materials, inventory, finished goods, and related information from point of origin to point of consumption.”

Amazon is characterized by a complex logistics system that consists of third-party logistics and private logistics department. In some countries, the company relies on postal services as a way of delivery. For example, despite the fact that the retailer owns its own logistics department in China (Beijing Joy Delivery), it also utilizes services of China Postal Express & Logistics (Li & Fan 2014). Amazon makes an emphasis on strengthening its e-commerce function; therefore, its logistics infrastructure hinges on the following logistics resources: “railway, highway, civil aviation, postal services, warehousing, and commercial networks” (Qin et al. 2014, p. 94).

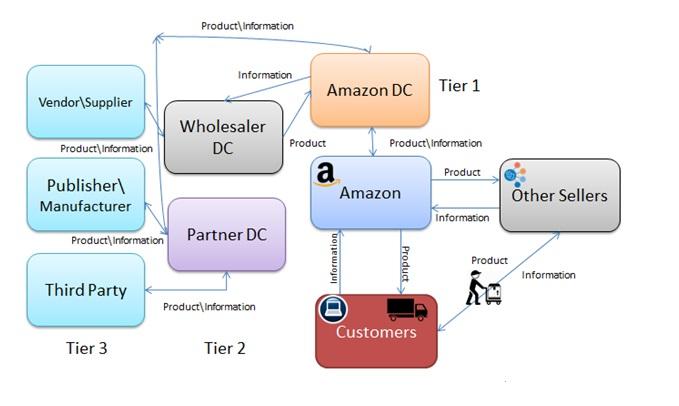

Furthermore, in an attempt to contain the cost of its deliveries, which exceeded $15 billion in 2015, the company has started an innovative on-demand delivery service—Amazon Flex (Saito 2016). The service supplements already existing Prime Now niche delivery models and offer one-hour delivery. The scheme relies on the use of freelance drivers, which allows to substantially reduce the cost of delivery. Moreover, a recent announcement by the company’s Chief Executive Officer (CEO), Jeff Bezos, reveals that it “eventually wants to use drones to deliver packages to customers within 30 minutes” (Dinham 2016, para. 6), thereby cutting its logistics costs. Figure 2 shows the company’s supply chain.

Analysis

Inventory

Inventory management is a key part of supply chain management the efficiency of which can spell a difference between success and failure of an organization. According to an industry report issued by the US Department of Commerce, more than $522, 000 million was held in inventory by retailers in 2013 (cited in Chaffey 2015). Therefore, the tech giant tries to carry as little inventory as possible. For example, almost all books sold by the company are not stored in distribution centers but supplied directly from publishers to buyers, which is an effective method of minimizing storage costs for slow-moving items (Lau, Nakandala & Shum 2016).

The company uses a multi-tier inventory model, which is an extremely efficient approach to managing multiple inventory locations. Figure 3 shows the directions of physical and information flows in the model.

It is clear from the picture that the physical flow of products starts from third party vendors and manufacturers (tier 3), proceeds through wholesaler and partner distribution centers (tier 2), and ends at Amazon distribution centers. Despite the fact that such an approach allows the company to preserve a low inventory level, it is associated with multiple complexities such as demand forecast, redundant safety stock, and a bullwhip effect, which creates a demand distortion (Liu 2013).

In order to facilitate its replenishment decisions, Amazon utilizes a wide range of custom optimizing tools that analyze sales history data and increase visibility across its demand chain (Ivanov, Tsipoulanidis & Schonberger 2017). The company maintains an inventory of millions of products; therefore, it is a heavy user of both private and outsourced IT solutions. Currently, the retailer’s central data warehouse consists of 28 Hewlett Packard servers, each of which contains four CPUs (OPEP 2015).

Given that Amazon works with third-party sellers, in order to ensure that its reputation is not damaged, the tech giant provides its partner companies with custom inventory management solutions (Grundey 2015). The company’s software helps third-party sellers to integrate their inventory data from multiple sources, thereby reducing a rate of error occurrence and increasing customer satisfaction.

It is extremely important since accurate product availability is a key to increased sales and revenues (Wallace & Xia 2014). Also, the system allows Amazon customers to offer items even if they are not currently in stock, which is an attractive trend in e-commerce (McAvoy 2016). A recent retail industry report reveals that more than 63 percent of consumers show a propensity for purchasing at online stores that support this technology (AGC Partners 2016).

Reverse logistics is a part of Amazon’s inventory management strategy. It has to do with the fact that from 25 to 50 percent customers return their online purchases (Manners-Bell 2014). In order to reduce the number of returns, the company urges its venders to add detailed descriptions of goods they sell as well as to feature high-resolution pictures of them. Moreover, the e-retailer has strict packaging policies. For example, those vendors that fail to polybag or properly bubble wrap items are charged a packaging fee (AMZ Advisers n.d.).

Warehousing

Being the largest e-commerce retailer in the world, Amazon requires effective warehousing that is capable of supporting multiple delivery options. The size of the company’s warehousing and fulfillment centers varies greatly and averages around 62, 000 m2 (Manners-Bell 2014). The location of its warehousing/distribution facilities is an important consideration for Amazon since state incentives and sales taxes substantially differ across the US. As a result of such differences, the e-retailer has been forced to strategically locate its facilities “closer to metropolitan areas in which there are larger concentrations of the customer” (Manners-Bell 2014, p. 74). The attempt to extend its same-day delivery capacities is a continuation of the strategy to cut warehousing costs.

Amazon also locates its warehouses close to major transportation hubs used by UPS and FedEx. These companies rely on rail routes; therefore, Amazon’s major warehousing centers are located in Tennessee, Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Ohio. Such warehouses are filled with robotic shelves manufactured by Kiva Systems that automate many warehousing tasks (Knight 2015). Human-machine collaboration is a key feature of all warehouses of the company, which reduces the rate of mistake occurrence and reduces operations costs.

Transportation

Until recently, Amazon has been outsourcing its transportation function. It has to do with the fact that when a company hires a third-party provider, it is able to “take assets off the balance sheet whilst retaining complete control of transport management” (Manners-Bell 2014, p. 21). However, despite the global tendency to outsource logistics activities, the company has started realizing its ambitious plan of entering into the logistics business. Sharma (2016) explains the company’s move by the inability of UPS, FedEx, and the US postal service to handle Amazon’s deliveries the demand for which is constantly on the rise.

In a bold move to cut its reliance on third-party transportation companies, the e-retailer has leased 20 Boeing freighter planes (Rao 2016) By doing so the company will be able to improve its bottom line and even carve off a share of the logistics market. Amazon has also strengthened its logistics presence in China by opening Beijing Century Joyo Courier Services in 2015 (Schreiber 2016). It is an extremely smart move considering that the company’s transportation costs have risen from $6.6 billion in 2013 to $8.7 in 2014 (Rao 2016).

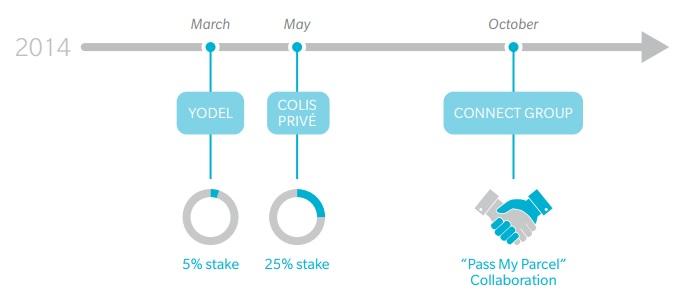

Amazon also invests heavily in transportation in an attempt to become a major player in the European logistics business. As of 2014, the retail giant was in control of 6, 700 delivery trucks owned by a European logistics company—Yodel (Lierow, Janssen & D’Inca 2016). By extending its capacity in Europe, Amazon is capable of delivering more than 170 million shipments annually in the UK (Lierow, Janssen & D’Inca 2016). Due to partial ownership of a delivery logistics company Colis Prive, Amazon’s 1, 700 delivery trucks that operate in France manage to transport more than 25 million parcels per year (Oliver Wyman 2015).

There is plenty of room for expanding the company’s transportation capacities abroad for more than 180, 000 delivery trucks traverse Europe each day (Oliver Wyman 2015). Figure 4 shows the company’s stakes in major European delivery companies.

As has been mentioned in one of the previous sections of the paper, Amazon contracts freelance drivers to deliver its packages. Such an approach to transportation is supported by the development of new information and communication platforms and is called crowd logistics. Despite the fact that the method is still in infancy, it is already disrupting the traditional field of logistics (Mehmann, Frehe & Teuteberg 2015). The use of crowd logistics in last-mile delivery is associated with substantial cost reduction, which is a central part of the company’s logistics model.

Packaging and Handling

Packaging and handling of items sold by Amazon are automated to a great extent. All fulfillment centers of the company work in coordinated harmony with robots that increase the productivity of human labor (Knight 2015). The flow of products through the centers is controlled by computer systems that track their arrival and dispatch. Sophisticated scanners operated by the company workers help to recognize the dimensions of each product and allocate a proper amount of packaging material. Robotic shelves are even capable of identifying and sorting items destined for individual customers (Knight 2015). Also, all boxes are weighted before shipment to avoid mistakes.

In order to make unpacking easier for its customers, the company has launched two packaging certification initiatives: frustration-free packaging and e-commerce ready packaging (Amazon 2014). These initiatives help to ensure that Amazon’s vendors adhere to standardized packaging requirements, thereby improving customer experience and optimizing the handling and transformation of items. The initiatives regulate shape, marking, labeling, and barcode requirements of vendors’ packaging (Amazon 2014).

Problems and Recommendations

Green Logistics

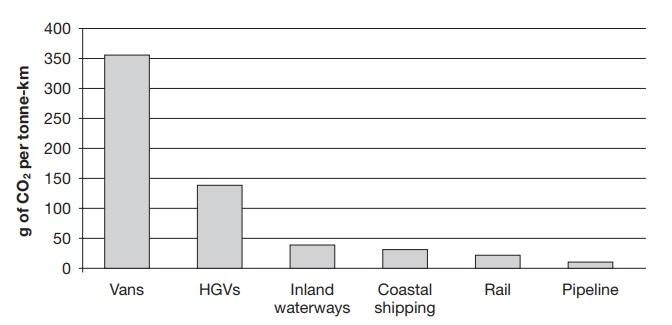

Despite the fact that the company’s e-commerce-ready packaging program, regulates the use of recyclable materials and enhances customer experience, Amazon’s efforts to make its logistics greener are still lacking in both scope and quality. The company relies on three freight transfer modes: road, rail, and water. Unfortunately, the environmental impact of these modes is quite damaging. Figure 5 shows the average CO2 emissions per tonne-kg.

It is evident from the picture that rail freight relates to fewer environmental effects in terms of CO2 emissions. It means that a recent company’s move to purchase delivery trucks is not viable from a sustainability perspective. By making its delivery more environmentally friendly, Amazon will be able to improve its logistical value proposition, thereby making the company more attractive in the eyes of its customers and investors. Therefore, the company has to shift its focus from delivery vans to rail and water modes of transportation.

Swarm intelligence is an IT approach to solving complex problems that can be effectively utilized to reduce the company’s carbon footprint. The ant colony optimization (ACO) is a swarm intelligence algorithm that mimics the behavior of foraging ants (Zhang et al. 2015). The application of the algorithm can help Amazon to find the shortest routes to distribution facilities, thereby optimizing its supply chain design. A chaotic particle swarm optimization (CPSO) is another application of swarm intelligence that might prove useful in making the company’s transportation less damaging for the environment. Venkatesan and Kumanan (2012) argue that the algorithm is capable of streamlining any supply chain network.

Amazon can also make use of SEAMO2, which is an algorithm developed by Harris and associates. Using the mix of integer programming and aggregated data analysis, the algorithm helps to “establish the best allocation of customers to serving facilities” and provides “good quality trade-off solutions” (Harris, Mumford & Naim 2014, p. 19). In addition to making the company’s logistics more sustainable, this solution will also help to reduce Amazon’s operations costs.

Aerial Package Delivery

Amazon logistics department has recently been under a lot of pressure due to the implementation of the Amazon Prime program that relies on freelance drivers. A scoop from the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) reveals that the company’s delivery workers are regularly breaking speed limits in an attempt to stay on schedule and deliver up to 20 packages per day (Monaghan 2016). Furthermore, the workers are forced to spend more than 11 hours a day driving, which is against the law (Monaghan 2016). Also, Amazon drivers in the UK receive much less than the national minimum wage.

Finally, driven by the desire to cut the costs of the program, Amazon has allowed independent vendors to ship directly to Prime customers. Kline (2015) argues that this decision might leave the company “exposed to any shipping problems its partners may have” (para. 6). These problems are grounds for a lawsuit that might substantially damage the reputation of the company. Also, the relinquishing of control over the delivery of its products is fraught with refunds.

Several years ago, the e-commerce giant announced its intention to start a drone delivery program. The project is dubbed Prime Air, and its core idea is the utilization of unmanned aerial vehicles in logistics. It can be argued that in order to ameliorate the issues associated with its original Prime service, the e-retailer has to invest heavily in Prime Air instead of expanding its fleet of cargo vehicles for the last mile delivery. It will help to improve the logistics operations of the organization by reducing legal risks and cutting its reliance on FedEx and UPS.

From the financial point of view, the operation is feasible since there would be no shortage of people willing to receive their packages in under two days. It is projected that despite its numerous drawbacks and inefficiencies, Amazon Prime memberships will exceed 25 million this year (Vempati et al. 2017).

Ark Invest, a developer of innovative investment strategies, has outlined a cost-benefit framework showing that in comparison with ground transportation, aerial delivery with the help of unmanned vehicles is a much cheaper and effective delivery option (Keeney 2015). The company’s publication shows that the retailer will be capable of delivering a package in under 30 minutes while charging its customers only $1 (Keeney 2015). There is no doubt that this analysis contains numerous gaps due to a lack of information on Amazon’s demand intervals across different areas. Furthermore, current regulations of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) pose many restrictions on commercial drone flights. However, if the company is able to get approval for its operations, it will get access to the untapped market of aerial delivery.

The feasibility of drone delivery has been proven in China where several companies have started delivering goods through the air (McKinnon 2016). The country’s experience proves that the likelihood of the emergence of such services in the US is also predicated on their logistical trade-offs. However, in order to explore the potential of air delivery, Amazon will have to reshape its current stockholding points. It has to do with the fact that major logistical facilities of the company “serve areas with radii of hundreds of kilometers, vastly greater than the typical catchment area of a drone” (McKinnon 2016, p. 623).

Keeney (2015) claims that the cost of a major overhaul of the company’s infrastructure will approach $50 million. In addition to retrofitting existing warehouses, Amazon will have to hire additional workers ($300 million), acquire a fleet of small octocopters ($80 million), and spend up to $350 million per year in operating expenses (Keeney 2015). However, given that numerous researchers confirm the feasibility of aerial delivery operations, Amazon should be working on the development of a drone fleet rather than expanding the number of its trucks.

Conclusion

The paper has analyzed the logistics operations of the Amazon and discussed two major areas of improvement: green logistics and Amazon Prime. After outlining the intricacies of the company’s inventory, transportation, packaging, handling, and warehousing, the paper has provided recommendations for improving Amazon’s logistics value proposition by making the company’s transportation greener. It has also been argued that the tech giant has to invest more heavily in the development of drone delivery services rather than concentrating on the expansion of its truck fleet. The recommendation has been based on the findings of numerous studies that point to the fact that drone delivery can support the rapid rate of growth of e-commerce by making last-mile delivery services more efficient.

Reference List

AGC Partners 2016, The retail industry disruptors: speciality online retailers and marketplaces take centre stage. Web.

Amazon 2014, Amazon packaging certification guidelines. Web.

Amazon n.d., Subsidiaries. Web.

AMZ Advisers n.d., Amazon chargebacks: avoiding and handling them smoothly. Web.

Bowersox, D, Closs, D, Cooper, M & Bowersox, J 2013, Supply chain logistics management, 4th edn, McGraw-Hill, New York, NY.

Chaffey, D 2015, Digital business and e-commerce management: strategy, implementation and practice, 6th edn, Pearson, London.

Dinham, P 2016, ‘At a loose end? Amazon will pay you to deliver its packages as it pushes to get all its goods to customers within just half an hour of ordering’, Daily Mail. Web.

Frazier, E 2016, At Amazon, supply chain innovations deliver results. Web.

Goldman, D 2017, Walmart, Amazon expand battlefield in price war. Web.

Grundey, J 2015, How an Amazon inventory management system helps you maximize earnings. Web.

Harris, I, Mumford, C & Naim, M 2014, ‘A hybrid multi-objective approach to capacitated facility location with flexible store allocation for green logistics modelling’, Transportation Research, vol. 66, no. 2, pp. 1-22.

Ivanov, D, Tsipoulanidis, A & Schonberger, J 2017, Global supply chain and operations management: A decision-oriented introduction to the creation of value, Springer, New York, NY.

Keeney 2015, How can Amazon charge $1 for drone delivery?. Web.

Kline, D 2015, Is Amazon making a mistake with two new delivery methods?. Web.

Knight, W 2015, Inside Amazon’s warehouse, human-robot symbiosis. Web.

Lau, H, Nakandala, D & Shum, P 2016, ‘A case-based roadmap for lateral transhipment in supply chain inventory management’, Journal of Information Systems and Technology Management, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 29-37.

Li, Y & Fan, R 2014, The coordination of e-commerce of Amazon.com. Web.

Lierow, M, Janssen, S & D’Inca, J 2016, ‘Amazon is using logistics to lead a retail revolution’. Web.

Liu, Y 2013, ‘An approach to real multi-tier inventory strategy and optimization’, Research Journal of Applied Sciences, Engineering and Technology, vol. 6, no. 7, pp. 1178-1183.

Manners-Bell, J 2014, Global logistics strategies: delivering the goods, Kogan Page, London.

McAvoy, K 2016, What traditional retailers can learn from Amazon inventory management and technology adoption. Web.

McKinnon, A 2016, ‘The possible impact of 3D printing and drones on last-mile logistics: an exploratory study’, Built Environment, vol. 42, no. 4, p. 617-628.

McKinnon, A, Cullinane, S, Browne, M & Whiteing, A 2012, Green logistics: improving the environmental sustainability of logistics, Kogan Page, London.

Mehmann, J, Frehe, V & Teuteberg 2015, ‘Crowd logistics—a literature review and maturity model’, 4th International Conference on Logistics (ICL) conference proceedings, Hamburg, Germany, pp. 117-134.

Monaghan, A 2016, ‘Amazon drivers admit to speeding due to tight delivery schedule’, The Guardian. Web.

Oliver Wyman 2015, Amazon’s move into delivery logistics. Web.

OPEP 2015, Inventory management at Amazon. Web.

Qin, Z, Chang, Y, Li, S & Li, F 2014, E-commerce strategy, Springer, New York, NY.

Rao, L 2016, ‘Amazon is leading 20 Boeing planes to create an air cargo network’, Fortune. Web.

Richardson, D, Castree, N & Marston, R (eds) 2017, The international encyclopaedia of geography, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ.

Saito, M 2016, ‘Exclusive: Amazon expanding deliveries by its ‘on-demand’ drivers’, Reuters. Web.

Schreiber, Z 2016, Amazon logistics services—the future of logistics?. Web.

Sharma, R 2016, Making sense of Amazon’s move into logistics (AMZN). Web.

Taniguchi, E & Thompson, R 2015, City logistics: mapping the future, CRC Press, New York.

Vempati, L, Crapanzano, R, Woodyard, C & Trunkhill, C 2017, ‘Linear program and simulation model for aerial package delivery: a case study of Amazon Prime Air in Phoenix, AZ’, 17th Aviation Technology, Integration, and Operations (AIAA) conference proceedings, Denver, Colorado, CA, pp. 24-38.

Venkatesan, S & Kumanan, S 2012, ‘A multi-objective discrete particle swarm optimisation algorithm for supply chain network design’, International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technologies, vol. 64, no. 1, pp. 1333-1343.

Wallace, W & Xia, Y 2014, Delivering customer value through procurement and strategic sourcing: a professional guide to creating a sustainable supply network, Pearson Education, London.

Wingfield, N & Merced, M 2017, ‘Amazon to buy Whole Foods for $13.4 billion’, The New York Times. Web.

Zhang, S, Lee, C, Chan, H, Choy, K & Wu, Z 2015, ‘Swarm intelligence applied in green logistics: a literature review’, Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 154-169.