Despite the popularization of policies treating sexual and gender minorities, American society is still considerably hostile towards people not conforming to hetero- and cis-normative standards. Minority stress and marginalization of these people prevent them from being meaningful members of society and thus put them under unfavorable circumstances where they experience inequality and violence. Transgender individuals are an exceptionally vulnerable social group, as they face increased violence and frequently become harassed, assaulted, and even killed (HRC, 2019). Such attitudes are caused by the increased ambiguity of transgendering comparing to lesbian or gay individuals.

The traditional binary framework of sex, gender, and sexuality implies that people can be categorized as male or female, masculine and feminine, heterosexual, or homosexual. Transgendering, however, suggests non-binary relationships between these concepts and causes confusion, which is often responded with violence. It is an umbrella term that describes all groups of people who are gender non-conforming (Tauches, 2016).

People often do not understand how to categorize such identities, so they perceive them as ‘wrong’ and thus treat brutally. Modern American society fails to provide an inclusive environment for gender non-conforming individuals. Unlike sexual minorities, transgender people are invisible, their population is not studied on the national level, their voices are not heard, and they are not legally recognized. Due to marginalization and stigma, many of them are not publicly out. That is why the extent of the problems that transgender people face cannot be known and appropriately addressed. Being in the shade evidently does not help to increase awareness and a positive attitude.

Moreover, they experience institutional and workplace discrimination that leads to marginalization and impacts their social well-being. Many transgender individuals are involved in sex work, substance abuse, and live in poverty. Such conditions strengthen the stigma and hostility, making transgender individuals targets of violence. According to Rojas and Swales (2019, September 30), strikingly high homicide rates for transgender individuals speak of the epidemic of transphobic violence. However, the total number of transgender killings is not known because the gender identity of victims is often excluded from the criminal records if it is non-binary.

The vicious circle of minority stress that leads to marginalization and the marginalization that contributes to the stigma has to be broken. However, the policies that address the problems of transgender people are scarce. Some of these people can access support as the members of the LGBTQ population, but adequate gender-identity oriented policies are necessary. The alarming homicide rates show that there is no time for hesitation regarding this issue.

That is why, along with long-term solutions that focus on education, some immediate actions should be taken to protect the lives of transgender people. Legal recognition and advocating for social justice for gender identity minorities are essential steps to tackling the problem. If transgender individuals did not feel fear and discrimination when communicating with the state institutions, they would ask for help and protection. However, when they remain in the shade, hardly any improvements can take place.

Current research addresses the problem of anti-LGBTQ violence in U.S. society, focusing on transgender individuals. Existing literature on the issue often fails to examine specific hate crime rates against gender identity minorities, including them into a mixed group together with sexual orientation minorities. However, they have different patterns of victimization and face disparate risks of being treated with violence. That is why the purpose of the research is to investigate the factors behind bias-motivated aggression against the LGBTQ community and discuss how they contribute to the design of the solutions.

To address this issue, the project intends to clarify several research questions. Firstly, it is going to discuss the different groups of LGBTQ communities and which of them are exposed to the highest risk of violence victimization. Additionally, the research will study the factors that contribute to anti-LGBTQ violence and its severity and anti-transgender violence specifically. Moreover, the project will analyze data on the violence rates against LGBTQ minorities in the U.S. and apply current knowledge to draw arguments. An in-depth analysis of the trends and violence rates will provide necessary insights into the problem and identify the areas where the solutions are most urgently required. Thus, the policies and improvements can be designed to protect the target groups, prevent violence, and save lives.

Content Knowledge

Life in America is undeniably harder for gender and sexual minority individuals than for non-minorities. That is why dealing with this problem is a pressing challenge for contemporary society. It is vital to recognize the essence of the crisis and identify what violence rates are experienced by LGBTQ community representatives are, and from what types of crimes they suffer. Apart from different categories of hate crimes, high homicide rates are evidently the most severe problem.

The reported epidemic of transgender killings undermines individual safety, causes fear, and calls for immediate action. According to Stotzer (2017), a murder of a gender minority representative takes place every three days across the world. The victims are generally under the age of thirty, which represents the prevalence of total gender minority identification among the age groups.

The problem of the official definition of gender minorities is especially worrying, according to the scholar, as the collected numbers of transphobic homicide are far from reflecting the real picture (Stotzer et al., 2017). The existing gender-binary model compromises the analysis of crime data regarding a variety of identities that do not fit into this framework. As formal data collections practices fail to reveal the frequency, nature, and extent of these homicides, so various NGOs apply their effort to contribute to the research.

Anti-transgender and anti-minority bias motivate a variety of hate crimes, including harassment, assault, bullying, and discrimination, that undermine the social well-being of individuals. The research by Cramer et al. (2018) investigates the patterns of hate crime victimization regarding different sexual identities.

The main contribution of the study is that it focuses on the extended range of minorities beyond lesbian, gay, or bisexual, including such identities as pansexual or questioning, while the formal data collection models fail to address them. The scholars identified that sexual minority individuals suffered from “higher rates of interpersonal violence compared to property crime victimization” (Cramer et al., 2018, pp. 476). Such insights suggest that prejudices and bias towards sexual minorities are strong predictors of hostility and potential victimization.

The pervasiveness of harassment, bullying, and assault among transgender and sexual minority individuals is a pressing issue, especially regarding adolescents and college-age people. Such crimes and overall hostility and discrimination lead to adverse effects such as suicide risk, substance abuse, and violence victimization. Several studies focus on the hate crimes against transgender youth and the implications of the bias.

Johns et al. (2019) explore an extensive sample of youth from 10 states, 1.8% of them identifying as transgender. The findings prove that “at a population level, transgender students are at disproportionately higher risk than are cisgender students for violence victimization, substance use, and suicide risk” (Johns et al., 2019, p. 67). According to Johns at al. (2019), alarming 34,6 percent of transgender youths have reported suicide attempts during the year preceding the research.

The analysis of contributing social factors of the environment where the transgender individuals live is essential to understand the reasons for violence and design preventive measures. Duncan and Hatzenbuehler (2014) study a similar age group of adolescents in Boston, focusing on the geographical prevalence of anti-LGBT hate crimes and its impact on transgender suicidality. The racially and ethnically diverse sample showed a high positive correlation between the suicidal ideation and the residence in the neighborhoods with high rates of transphobic hate crimes (Duncan and Hatzenbuehler, 2014). This research significantly contributes to the understanding of the factors that need to be targeted while solving the problem of transphobic violence.

Transgender and sexual-minority individuals also suffer from various types of sexual violence, including harassment, coercion, and sexual assault. These issues, as well as the problem of physical dating violence, have become the subject of numerous studies. Martin-Storey et al. (2018), for example, explore the “vulnerability among sexual and gender minority students with regard to sexual violence” (p. 701).

The scope of the research includes such types of sexual violence as unwanted sexual behavior, coercion, and sexual harassment. The findings support the earlier studies, proving that transgender or gender non-binary college students are exposed to higher risks of sexual violence than non-minorities (Martin-Storey et al., 2018). Cisgender males are recognized to have the lowest risk of becoming the victims of sexual abuse among the studied population, while the rates are substantially higher for cisgender females. However, gender non-binary or transgender individuals face three times higher likelihood of being sexually harassed or assaulted than the latter (Martin-Storey et al., 2018). These findings create serious implications for addressing sexual violence issues among sexual minorities and transgender individuals.

The research discussed above does not explore the questions of the abusers and their relation to the victims. The study conducted by Edwards et al. (2014) extends the scope of the sexual assault issue, adding physical dating violence and unwanted pursuit. The sexual violence incidence is compared for gender and sexual minority students and non-minorities. The findings provide disquieting data, as the rate of sexual assault of minorities is more than twice as high as that of non-minorities (24,3% and 11,0%).

Intimate partner violence accounts for 30,3% compared to 18,5%, while unwanted pursuit rate equals 53,1% to 36,0%, respectively (Edwards et al., 2014, p. 581). The scholars also explore the concept of minority stress that magnifies the risks for sexual minority victimization. Such factors as identity concealment, discrimination, victimization, and anticipated rejection contribute to the minority stress and overall well-being of individuals.

The analyzed scope of literature that explores the victimization issue proves that transgender and sexual minority individuals experience violence and hostility substantially more often than analogous cisgender populations. The main types of biased crimes against minority groups are homicide, hate crimes, such as bullying, harassment, or assault, and sexual aggression, including intimate partner violence. The issue is extremely pressing, as the pervasiveness of these crimes severely impacts the well-being of the whole social group, increasing the risk of suicide, substance abuse, and mental health issues. Additionally, the insights from the analyzed studies suggest that minority stress, the context of the neighborhood, and sexual risk behaviors are contributing factors to transphobic crime victimization.

Although all representatives of sexual and gender minorities experience the different extent of prejudiced attitudes and suffer from discrimination, there are groups among them that are exposed to higher risks of victimization. Transgender individuals are especially exposed to violence and hostility. That is why Haynes and Schweppe (2017) emphasize the importance of addressing the issue of transgender-related hate crimes separately from other anti-LGBT crimes, “as a category in its own right” (p. 112). According to scholars, today, such cases often estimated along with homophobic violence or merely ignored (Haynes & Schweppe, 2017).

Moreover, different subcategories of trans individuals, such as non-binary, intersex, or agender, require particular concern as they cause confusion in society and thus are treated with increased hostility. The reason that transgender individuals experience higher violence rates compared to cisgender people, and even to other minorities, is that the conflict with the traditional beliefs is more intense in their case. Apart from breaking down the gender-binary social structure, they cause misunderstanding of their sexual identity.

Many researchers have concluded that transgender individuals are the group of higher victimization risk compared to other minorities. However, violence rates are not homogeneous across the gender-minority population, as such factors as race, ethnicity, or gender contribute to the risk of violent attitude. Dinno (2017) explores the demographic parameters of transgender homicide statistics to reveal the pattern of specific risks. Although total rates of transgender homicide are lower than those of cisgender, the situation strikingly changes when the focus shifts to young racial minority transfeminine people.

According to Dinno (2017), homicide rates of Black and Hispanic transgender women in the U.S. are significantly higher than for cisgender women. Among 69 transgender individuals killed from 2010 to 2016, 68 were transfeminine, and 67 of them represented a racial minority (Dinno, 2017, p. ). These numbers show a strong presence of the risk group that requires increased protection against hate crimes and homicides. The bias against transgender individuals, in this case, is strengthened by the traditional perception of masculine dominance, and racial prejudice, making transfeminine Black and Latina individuals the targets of hate and hostility.

Transgender women are also exposed to higher risks of domestic violence and IPV (intimate partner violence). According to Garthe et al. (2018), IPV was reported by 42% of transgender women, the majority of who describe it as trans-biased violence. Scholars claim that the risks of IPV are higher due to such minority stressors as discrimination, unequal daily treatment, or transgender-related victimization (Garthe et al., 2018).

These stressors, combined with overall higher rates of IPV against women, contribute to increasing victimization rates regarding transfeminine individuals. That is why the policies aiming to solve domestic violence should account for transgender women as the group exposed to more frequent cases of aggression and assault.

Multiple studies that focus on specific age groups or environments align with the ideas about the prevalence of hate crime victimization among transgendered women. Griner et al. (2017) contribute to the existing body of the research comparing the violence rates against transgender college students to their cisgender peers. The scholars claim that gender minorities experience an elevated risk of experiencing sexual violence (Griner et al., 2017).

Interestingly, the researchers argue that the age group from 16 to 24 is exposed to higher overall rates of victimization, especially on campus. The combination of minority status and belonging to a vulnerable age group poses an elevated danger to transgender students. This insight is critical in designing the policies that can be implemented on campus to protect young transgender individuals.

The exploration of the literature concerning risk groups of hate crime victimization proves that transgender minorities experience violence victimization even more often than sexual minority representatives. Moreover, the age factor matters, as college-age individuals are experiencing increased hostility and violence. Additionally, women generally suffer increased victimization due to masculine dominated bias.

Thus transfeminine individuals endure sexual abuse and hate crime victimization more often compared to their transmasculine peers. Racial intolerance provides another subject for hostility and discrimination of transgender people. Thus the life in the U.S. is especially hard for young Black or Hispanic transgender women, who represent the majority of transgender homicide victims.

With an attitude as one of the most influential predictors of actual behavior, it is vital to explore the pervasiveness of beliefs and bias regarding transgender individuals in U.S. society. An in-depth analysis of such a pattern will help to address the issue and design the policies that challenge the problem of anti-transgender violence. Flores (2015) seeks to study the trends in public opinion and the support of transgender individuals.

The scholar reports the scarcity of research regarding the attitudes of the Americans towards gender minorities, expressing no confidence that the majority of the population understands the concept correctly (Flores, 2015). According to the respondents’ reports being well-informed, along with personal familiarity with someone who is transgender, are the main factors contributing to trans-positive attitudes (Flores, 2015). That is why education and awareness is one of the critical directions of policy development.

Despite the increased awareness and growing acceptance of gender and sexual diversity, anti-transgender biases persist in the U.S. Many people are not willing to accept transgender people in society, treating them with violence and hostility. Garelick et al. (2017) seek to explain the foundations of transphobic attitudes and motivating causes to promote a better grasp of the issue and its potential solutions. Scholars claim that biphobia and transphobia are similar types of biases that they have the same roots. In essence, they both challenge the binary framework of gender and sexuality, causing ambiguity and misunderstanding (Garelick et al., 2017).

The researchers explain higher rates of transphobia compared to homophobia by the inability to place transgender individuals into their perceived social structure based on dualism (Garelick et al., 2017). Feeling the invalidity of the concept, people tend to regard it as wrong and, thus, having no right to exist.

The profound explorations of demographic predictors of attitude will help to assess what groups have increased risks of developing anti-transgender prejudices and what are the factors behind them. Worthen (2016) presents research on the correlation between the sexual orientation of college students, their gender identity, and transphobic attitudes. As the findings illustrate, heterosexual men tend to be less supportive of the transgender population than heterosexual women (Worthen, 2016). This trend can be explained by perceived masculinity attributes that are challenged by MtF transgender individuals.

Feminist identity, on the contrary, was found to be the predictor of the positive attitude of women toward MtF gender-variant people. The scholars conclude that transphobia undermines both models of hetero- and cisnormativity, and thus, provokes unacceptance and hostility (Worthen, 2016). Apart from the overall bias towards social minorities, the inability to categorize transgender individuals into any of the traditional frameworks causes ambiguity, which magnifies hostile attitudes.

Content Application

The analysis of rates and trends of hate crimes against sexual and gender minorities provides essential insight into the problem and helps to identify risk groups and factors that contribute to victimization. Thus, the research intends to critically analyze the existing data on rates and types of bias-motivated crimes against the LGBTQ community members. Retrospective data is collected from the yearly nationwide reports provided by federal agencies and NGOs, including FBI, NCAVP (National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs), and HRC (Human Rights Campaign).

The data is drawn from the last five reported years, while the yearly reports are summarized, and aggregate numbers are analyzed. The reason for doing this is that the research does not focus on the dynamics, but instead, it aims to find patterns visible on the more extended periods. Moreover, yearly homicide reports provide relatively small samples and summarizing helps to draw more statistically meaningful insights.

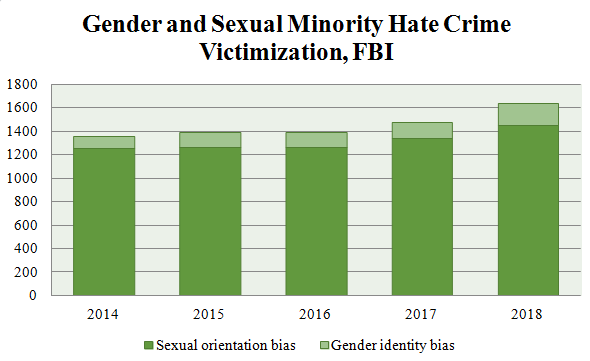

The rates of bias-motivated crimes against the LGBT population speak of the public attitudes towards this social group. According to FBI (2020), hate crimes include intimidation, simple or aggravated assault, vandalism or property damage, homicide, and rape, where the primary motivation is the victim’s belonging to a specific social group. Figure 1 represents the data collected by the FBI regarding the total count of such cases against the LGBTQ representatives over the recently reported years (FBI, 2020). The aggregate yearly numbers include crimes of different severity, the majority of which are mild.

As the chart suggests, the quantity of bias-motivated crimes against LGBTQ people steadily grows every year, which is the worrying trend. The total number and of transgender victims of hate crime also increases. The proportion of gender minority people experiencing violence is relatively small, which represents the size of the population in relation to sexual minorities. However, 24.77% of sexual minority cases were identified as a mixed group of LGBTQ, including transgender, so the proportion of gender identity biased crime should be taken cautiously in this case (FBI, 2020). Moreover, the overall underreporting of such cases should be kept in mind while analyzing the official data.

In addition to a total trend of growing anti-LGBTQ hate crimes, it is critical to assess what social groups are the most vulnerable and what factors can be behind this violence. NCAVP (National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs) collects data on different types of crimes that target the LGBTQ population across the U.S (AVP, 2019). They break down the collected data according to gender identity, race, age, and sexual orientation of the victims to understand the vulnerable groups of the population. The numbers discussed here represented the aggregate statistics of the last five years reported by the organization (2012-2016).

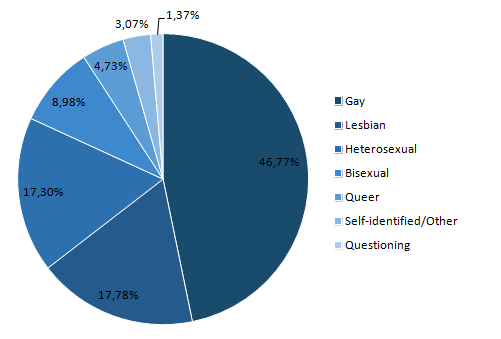

Among sexual orientation minorities, gay men are targeted in almost half of the total cases, while lesbian comprise only 17,78% of hate crime survivors (Figure 2). This pattern supports the research by Worthen (2016), who claims that homosexual men are the most frequently offended group targeted by heterosexual men. 17,30% of heterosexual victims are assumed to belong to gender minorities, but their ratio should not be excluded to this number, as some transgender people identify as homosexual.

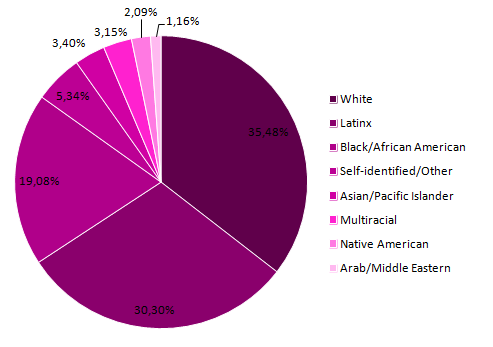

Belonging to the racial or ethnic minority is assumed to be one of the factors contributing to violence victimization risk among sexual and gender minorities. The data provided by AVP (2019) proves the assumption as 64,52% of hate crime survivors are people of color (Figure 3). This proportion does not represent the racial pattern of the U.S. population, proving that racial minorities are exposed to higher victimization rates. Thus, race magnifies the negative attitude towards sexual or gender identity minority, causing an increased risk of violence victimization.

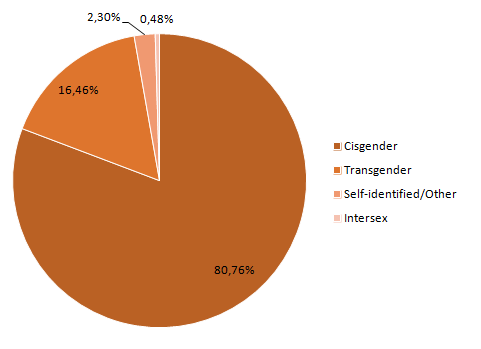

The age distribution of the victims in the reports is consistent with the previous studies. The majority of hate crime survivors are reported to be from 20 to 30 years old (34,74%) with a slightly smaller proportion (24,20%) of people in the age of 30-39 (AVP, 2019). The majority of the survivors were cisgender (80,76%), which proves that they are victimized due to their sexual identity (Figure 4). Gender non-conforming individuals account for 19,24% of the cases, which is due to their smaller overall population.

The statistics presented by AVP suggests that race and age are significant risk factors of hate crime victimization. However, the distribution of gender and sexual identities may not correspond to the rates of violence, as the population size of these groups in the U.S. is unknown.

Moreover, the data on survivors does not give insight into the severity of the cases, many of which are mild. Additionally, lower discrimination rates of sexual minorities compared to transgender people may lead to higher rates of reporting, while many crimes against gender non-conforming people remain unknown because of fear and stigma. That is why it is essential to consider the distribution of the population on the sample of severe crimes, such as homicide.

While the proportion of transgender survivors of bias-motivated crimes is relatively small, the fatal violence rates strikingly differ. Out of the total number of LGBTQ murders for five years, 64,52% were transgender (AVP, 2019). The disparity of the rates between homicide and overall violence rates demonstrates that crimes against gender non-conforming individuals are far more brutal than those against sexual orientation minorities.

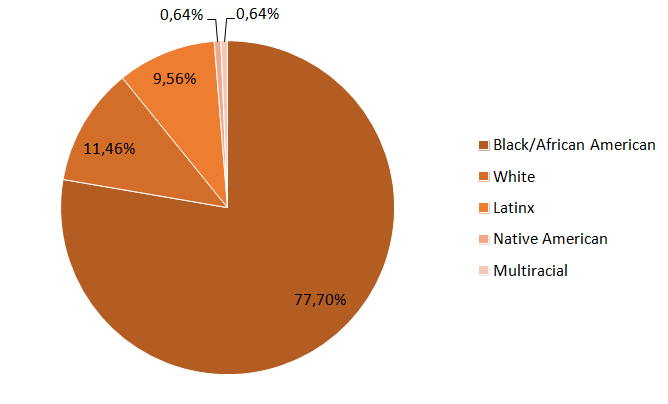

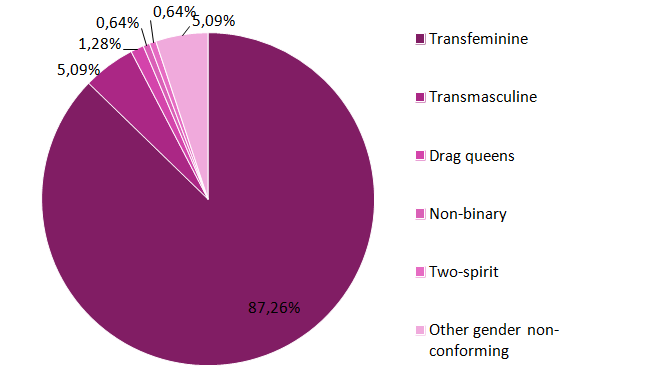

Human Rights Campaign (HRC) has released a report that focuses specifically on transgender homicide from 2013 to 2019. The statistics demonstrate alarming racial, and gender disparity of the victims, as the majority of them are transgender women of color (HRC, 2019). Figure 5 illustrates the racial proportion of the victims, showing that only 11,46% of them were white. African Americans represent the vast majority of the victims (77,70%) being the most vulnerable group among transgender individuals. Moreover, 87,26% of the victims identified as transgender women, proving gender to be another violence risk factor (Figure 6). Thus, American society is particularly violent to transgender women of color who comprise the highest proportion of transgender homicide victims.

The age groups of transgender homicide victims correspond to those of hate crime survivors. Out of a total of 157 people, more than 80 were in the age between 21 and 30 (HRC, 2019). Age might be a significant predictor of violence victimization, but it also might only represent the population of transgender individuals. It is assumed that many of the majority of them are currently under the age of thirty, although the exact numbers are unknown.

The statistics on transgender homicides reveals other social determinants that elevate the risk of violence victimization. HRC (2019) reports that 90% of the murders took place in districts “that had a poverty rate above the 2018 U.S. average of 11.8%” (p. 16). Moreover, 13-36% of the victims were involved in sex work, but the exact rate is undocumented due to the illegality of such activity. These factors contribute significantly to the risk of victimization, as people from marginalized districts who engage in illegal activity have no opportunities to seek for help. Lastly, HRC (2019) reports the disparities according to the U.S. census regions, with the majority of murders occurring in the South (58%) where only 35% of the transgender population is reported to live.

Content Integration

The numbers and rates of hate crimes discussed above support the findings of the previous research and suggest that LGBTQ representatives experience frequent hostility and violence. The most noteworthy conclusion drawn from the analysis is that transgender individuals are treated more violently compared to sexual minorities and non-minorities. The analyzed data proves that transphobic attitudes persist in American society making transgender individuals targets for violence, which in many cases leads to severe adverse outcomes and even death.

The ambiguity of the transgendering and the inability to fit into the binary framework provoke aggression, which is more critical than against cisgender sexual minority individuals. These negative attitudes are amplified when a transgender individual has other discriminated identity, such as race or feminine gender, or both. That is why the lack of education escalates hatred and makes transgender women of color vulnerable targets of prejudiced offenders.

The marginalization of these people at all social levels only aggravates the situation. Due to institutional discrimination, transgender individuals have little career opportunities and suffer from unequal policing. Poverty makes them engage in sex work, substance and alcohol abuse, which bring additional risks and make these people invisible to the state. Such social roles contribute to the stigma and, thus, increase hostility towards gender identity minorities. The geographic context is another risk factor for LGBTQ communities, as the crime victimization is higher in different neighborhoods, cities, states, and census regions.

Making a change in public opinion is a lengthy process that requires long-term solutions and policies. However, dozens of transgender people lose their lives every year and more suffer from biased violence. That is why urgent short-term policies are required, along with long-term programs. First of all, it is necessary to promote advocacy for social justice for LGBTQ individuals and especially gender identity minorities.

Moreover, all the cases of violence should be responded with legal procedures and public attention to ensure that they are investigated with proper diligence. Inclusion programs that help transgender individuals to become meaningful members of society are required to secure their visibility and safety. Decriminalization of sex work will help many marginalized individuals to ask for help and support openly without fears. Such policies should be developed with the focus on crisis areas across the country to protect transgender people exposed to the highest risk of violence.

Recognition of the transgender population on the federal level is a necessary stage in identifying and addressing the problems that this community faces. Without proper knowledge about gender identity minorities, the design of specific policies is inefficient or impossible. Legal recognition of transgender will help to create inclusive policies and opportunities for these people, as well as provide adequate physical and mental health support. Education of the population about transgendering is the essential long-term goal concerning this concept. Promoting such knowledge requires the immense joint effort of all stakeholders will be met with resistance, but in the future, it can eliminate the need for all other policies when the violence rates substantially decrease.

Conclusion

Being a transgender person who lives in the U.S. bears many challenges that include discrimination and violence. Current alarming trends prove that violence against the LGBTQ community is a critical issue in the U. S., and transgender individuals are treated with increased aggression and hostility. They have a substantially higher rate of hate crime fatality than other groups. Moreover, race and gender discrimination of transgender individuals increase the minority stress and aggravate hateful attitudes, making young transgender women of color the most vulnerable risk group. Social marginalization, poverty, and sex work involvement contribute to stigmatization and increase the violence and fatality risks for transgender people.

The evidence drawn from hate crime victimization reports is essential in designing social justice policies. Statistics helps to identify the most vulnerable groups and the most critical issues that should be addressed immediately.

An in-depth overview of the demographic parameters of hate crime victimization in the U.S. highlights the specificity of transphobic hate crime and proves that anti-transgender violence should be studied independently from anti-LGBTQ violence. Current research has several practical implications, as it provides essential information for policy development. As the findings suggest, specific long- and short-term programs that target transgender people specifically should be designed and implemented, focusing on different local contexts.

However, the research has several limitations that concern the quality of data collection sources. Transgender population size and demographic parameters lack adequate study, thus, emphasizing the directions for future research. Apart from scientific research, the issue requires real-life improvements, social activism, and promotion of justice that have to take place immediately to reduce the risks of human tragedy.

Works Cited

Anti-Violence Project (2020). Reports. Web.

Cramer, R. J., Wright, S., Long, M. M., Kapusta, N. D., Nobles, M. R., Gemberling, T. M., & Wechsler, H. J. (2018). On hate crime victimization: Rates, types, and links with suicide risk among sexual orientation minority special interest group members. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 19(4), 476-489. Web.

Dinno, A. (2017). Homicide rates of transgender individuals in the United States: 2010-2014. American Journal of Public Health, 107(9), 1441-1447. Web.

Duncan, D. T., & Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2014). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender hate crimes and suicidality among a population-based sample of sexual-minority adolescents in Boston. American Journal of Public Health, 104(2), 272-278. Web.

Edwards, K. M., Sylaska, K. M., Barry, J. E., Moynihan, M. M., Banyard, V. L., Cohn, E. S., … Ward, S. K. (2014). Physical dating violence, sexual violence, and unwanted pursuit victimization: A comparison of incidence rates among sexual-minority and heterosexual college students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30(4), 580-600. Web.

FBI (2020). Hate crime statistics. Web.

Flores, A. R. (2015). Attitudes toward transgender rights: perceived knowledge and secondary interpersonal contact. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 3(3), 398-416. Web.

Garelick, A. S., Filip-Crawford, G., Varley, A. H., Nagoshi, C. T., Nagoshi, J. L., & Evans, R. (2017). Beyond the binary: exploring the role of ambiguity in biphobia and transphobia. Journal of Bisexuality, 1-18. Web.

Garthe, R. C., Hidalgo, M. A., Hereth, J., Garofalo, R., Reisner, S. L., Mimiaga, M. J., & Kuhns, L. (2018). Prevalence and risk correlates of intimate partner violence among a multisite cohort of young transgender women. LGBT Health, 5(6), 333-340. Web.

Griner, S. B., Vamos, C. A., Thompson, E. L., Logan, R., Vázquez-Otero, C., & Daley, E. M. (2017). The intersection of gender identity and violence: Victimization experienced by transgender college students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 8, 1-22. Web.

Haynes, A., & Schweppe, J. (2017). LGB and T? The specificity of anti-transgender hate crime. In A. Haynes, J. Schweppe, & S. Taylor (Eds.), Critical Perspectives on Hate Crime (pp. 111-136). Palgrave Macmillan.

Human Rights Campaign (2019). A national epidemic: Fatal anti-transgender violence in the United States in 2019. Web.

Johns, M. M., Lowry, R., Andrzejewski, J., Barrios, L. C., Demissie, Z., Mcmanus, T., … Underwood, J. M. (2019). Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school students – 19 states and large urban school districts, 2017. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(3), 67-71. Web.

Martin-Storey, A., Paquette, G., Bergeron, M., Dion, J., Daigneault, I., Hébert, M., & Ricci, S. (2018). Sexual violence on campus: Differences across gender and sexual minority status. Journal of Adolescent Health, 62(6), 701-707. Web.

Rojas, R., and Swales, V. (2019). 18 transgender killings this year raise fears of an ‘epidemic.’The New York Times. Web.

Stotzer, R. L. (2017). Data sources hinder our understanding of transgender murders. American Journal of Public Health, 107(9), 1362-1363. Web.

Tauches, Kimberly (2016). Transgendering: challenging the ‘normal.’ In N. L. Fischer & S. (Eds.), Introducing the New Sexuality Studies (3rd ed., pp. 134-139). Routledge.

Worthen, M. G. F. (2016). Hetero-cis-normativity and the gendering of transphobia. International Journal of Transgenderism, 17(1), 31-57. Web.