Apple Inc.’s commercial success rests on its production scale based on the outsourcing of manufacturing function to Asia. The company’s triumph is paralleled by the rise of the world’s largest electronics contractor—Foxconn. Even though Apple Inc. has repeatedly professed its “ideals of corporate citizenship, environmental, labor, and social responsibility” in its annual reports and codes of professional conduct, it continues to exploit 1.4 million workers in China alone.

Large contract manufacturers in Asia that are vertically integrated into the company’s supply chain have to go along with price-setting practices that result in unfair treatment of workers and promote health and safety hazards. These and other practices of Apple Inc. can be viewed as the extraction of dark value from what might be called dark value chains.

According to Clelland, the approximate dark value of an iPad amounts to US$1, 077, which is two times greater than its retail price and ten times greater than the company’s operating profit margin. As a result of such value extraction-driven management practices, a wave of employee suicides has swept China.

In 2010 alone, 18 factory workers aged 17 to 25 and employed by Foxconn attempted suicide. These suicide attempts were instigated by a harsh production regime characterized by an excessively high production quota, an extremely limited number of breaks, and strict execution of manufacturing discipline. Therefore, it is necessary to explore the real price of Apple’s corporate success.

The paper will examine how global commodity chains and globalization have helped Apple Inc. achieve a dominant consumer electronics industry position. It will assess the power dynamics of the company’s supply chain using the framework of global commodity chains and global value chains.

The paper will argue that power asymmetry in the industry promoted by buyer-driven commodity chains allows Apple Inc. to pressure its production and logistic service contractors to constantly lower costs. It will also explicate exploitive structural relationships between the tech giant and commodity manufacturers that make possible massive transfers of value added at nodes of commodity chains’ global networks.

The paper will maintain that iPad production has become possible due to the following Apple Inc.’s practices: the appropriation of hidden labor excesses, extraction of unpaid inputs, and “surplus extraction through ecological externalities.” The research theme is directly related to the study conducted so far that shows that Apple Inc. has explored a global business model to achieve extremely low production costs of iPad, which is one of its flagship products.

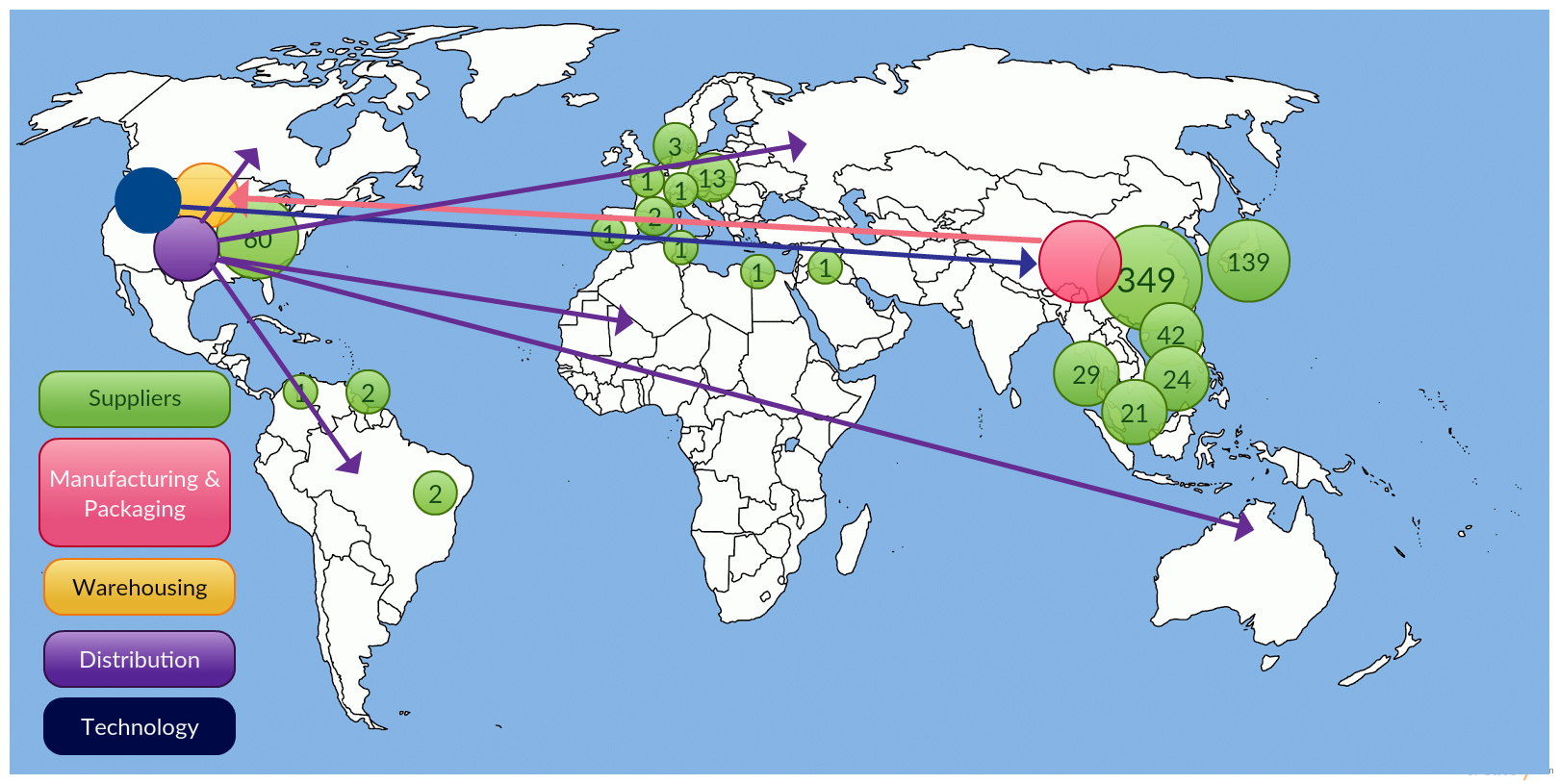

Figure 1 presents a map that demonstrates how the iPad travels across the globe. It indicates the sources of raw materials and technology for the commodity. The map also shows the places where the iPad is manufactured, packaged, and bought.

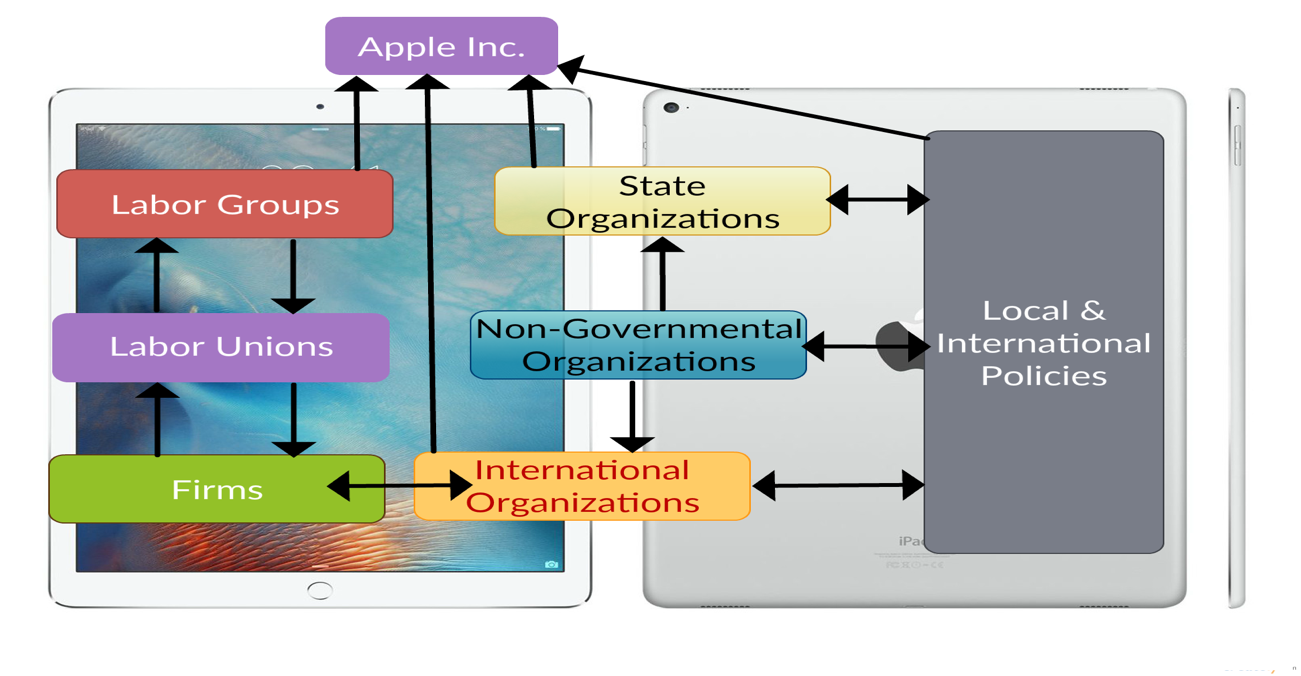

Figure 2 is an actor-network map. It includes the actors and organizations participating in the production of iPad and indicates the nature of the relationship between them.

Bibliography

Chan, Jenny. “A Suicide Survivor: The Life of a Chinese Worker.” New Technology, Work and Employment 28, no. 2 (2013): 84-99.

Chan, Jenny, Ngai Pun, and Mark Selden. “Apple’s iPad City: Subcontracting Exploitation to China.” In Handbook of the International Political Economy of Production, edited by Kees van der Pijl, 76-97. London: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2015.

Chan, Jenny, Ngai Pun, and Mark Selden. “The Politics of Global Production: Apple, Foxconn and China’s New Working Class.” New Technology, Work and Employment 28, no. 2 (2013): 100-115.

Clelland, Donald. “The Core of the Apple: Dark Value and Degrees of Monopoly in Global Commodity Chains.” Journal of World-Systems Research 20, no. 1 (2014): 82-87.

Kraemer, Kenneth, Greg Linden, and Jason Dedrick. “Capturing value in Global Networks: Apple’s iPad and iPhone.” Journal of World-Systems Research 14, no. 1 (2011): 64-73.

Litzinger, Ralph. “The labor question in China: Apple and beyond.” South Atlantic Quarterly 112, no. 1 (2013): 172-178.