Types of Innovation

The majority of businesses need help with innovation. Only 6% of executives are truly happy with their performance in terms of innovation, according to McKinsey (What is innovation? 2022). Due to this, it is challenging how few corporate leaders have the confidence or expertise to address the issue before it is too late (Lee et al., 2019). Generally speaking, disruptive, incremental, bincremental, and radical innovations differ significantly from what businesses are used to doing most of the time.

Disruptive Innovation

Since no system, method, or industry is immune to disruption, many find it beneficial to seek new disruptive discoveries. Reusing resources like technology can help generate new ideas that appeal to consumers (Marion & Fixson, 2020). To illustrate, consider the rise of the iPhone from Apple Inc., which popularized touch displays over conventional button phones. Disruptive innovations, like everyday commercial ventures, are unmanageable because they are riskier than incremental improvements (Sjödin et al., 2020).

Standardization is used to improve quality and create new goods and processes, but it is hard to apply to fresh concepts (Soni et al., 2020). New inventions cannot be valued by comparing them to existing products and services, which is another opportunity for improvement (Ceipek et al., 2020). Businesses can overcome this significant innovation challenge by using a different disruptive innovation strategy than they do for other projects (Pedersen et al., 2020). This shows that disruptive innovation makes innovations impossible to manage.

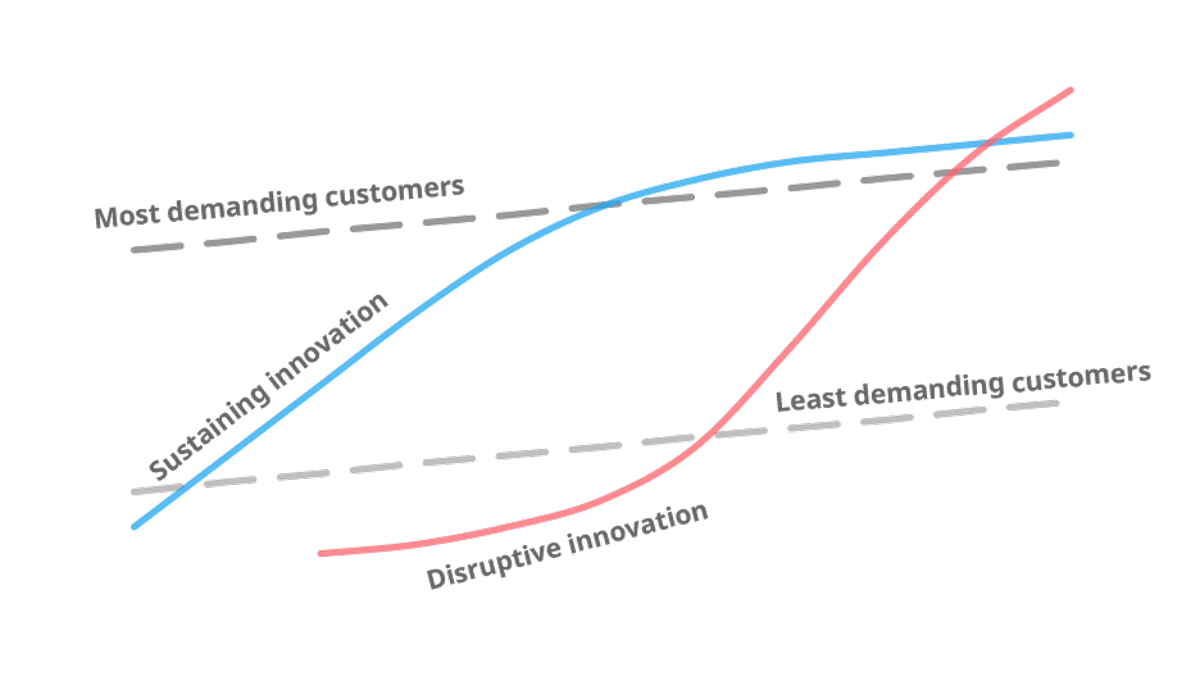

The Innovator’s Dilemma hypothesis provides insight into the widespread inability of businesses to manage innovation effectively. First innovations, especially those of a disruptive nature, are not as good as the ones already on the market (Breier et al., 2021). At this phase in the S-curve, the customer value is low since improving the product takes a long time and requires several iterations (see Figure 1) (Mendling et al., 2020). Established firms focus on serving increasingly demanding, high-end clients via their traditional value channels, while disruptive innovation first caters to a tiny and not-so-profitable customer base (Cichosz et al., 2020). Here is when the profit margins are the highest, which is why well-established businesses using logical decision-making processes frequently opt not to participate in disruptive ventures during their early stages.

Incremental Innovation

One of the most prevalent types of innovation people may face is incremental innovation. The same technology is used, but the firm does something to make it stand apart, like adding new features or altering the design. Whether it comes to software upgrades or adding new capabilities to smartphones, such as cameras and sensors, Samsung is a great example of a company that takes advantage of this innovation. Despite their relatively minor impact on short-term performance, incremental improvements are essential to sustained expansion and financial success (Afriyie et al., 2019). Although difficult to implement, their benefits are substantial (Elmo et al., 2020). Notwithstanding their importance to the advancement of society at large, its unpredictable enterprises cannot be brought under control, making it unmanageable.

Bincremental Innovation

Tech conglomerates like Amazon or Google frequently use bincremental innovations. They are able to offer items in new markets due to their combined knowledge, developed technology, and people resources. The entry of Amazon with Amazon Care into the healthcare industry is a prime illustration. It makes use of its extensive consumer base, experience creating apps and platforms, and other resources to offer its current skills to an untapped market. Although this invention is beneficial, small and medium-sized businesses will find it difficult to manage.

Radical Innovation

It is likely that radical innovation is the common person’s mental image of what innovation entails. For an innovation to be considered revolutionary, it must make use of cutting-edge tools and usher in wholly novel applications and services that create whole new markets (Gurzawska, 2019). Aeronautics’ progress and the introduction of airplanes by Boeing are examples of revolutionary progress (Rampersad, 2020). As a result, not only did the way people travel change drastically, but a whole new industry was born. Since it occurs accidentally when numerous employees engage in self-organization and learn from several failed initiatives, radical innovation is incredibly difficult to govern.

Types of Organization

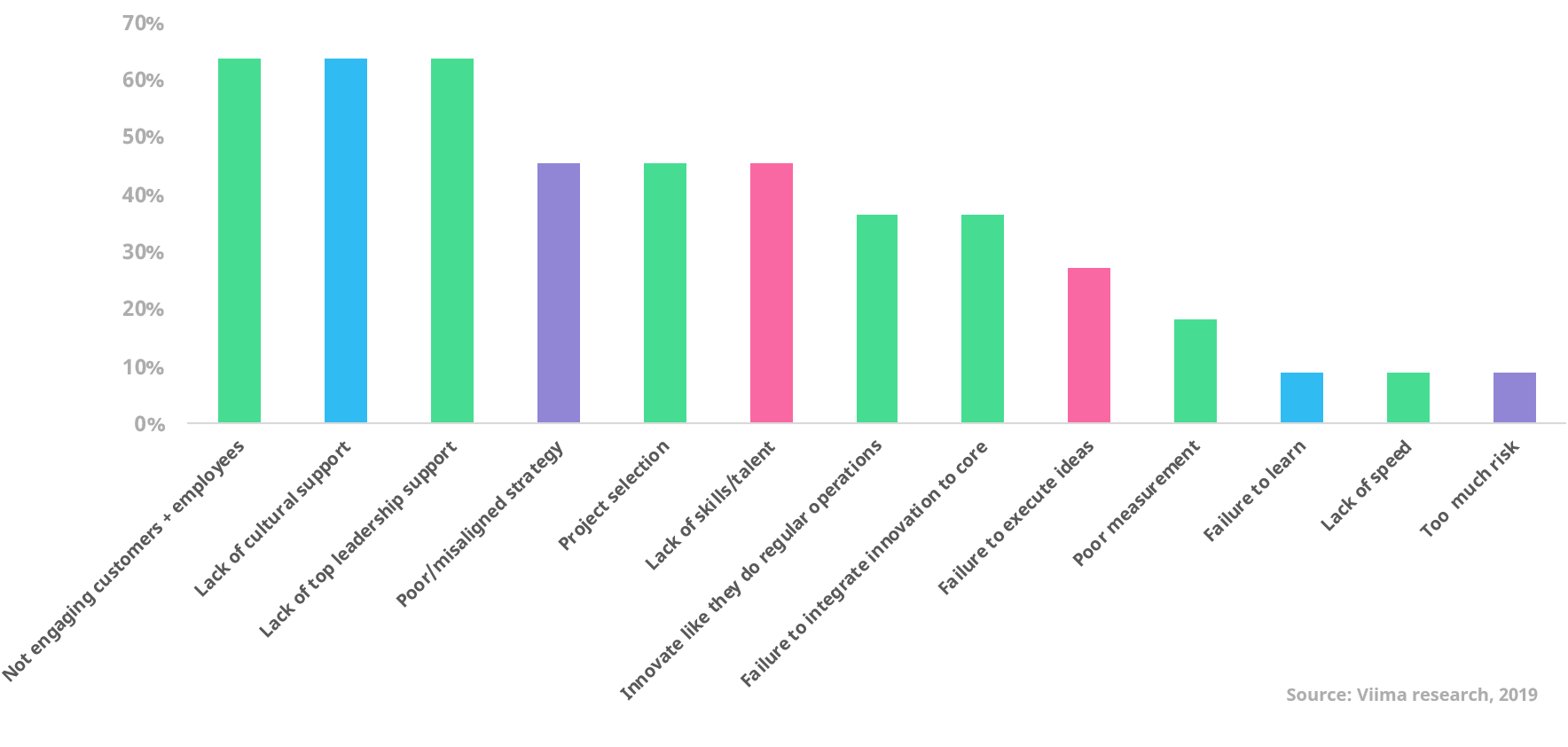

I have analyzed and gathered the facts to have a deeper comprehension of the challenges that many businesses are currently facing. As a result, I found a dozen complete studies available to the public that identify the variables that have the biggest influence, either positively or negatively, on innovation management (see Figure 2). A diverse set of factors influenced each of the four essential facets of innovation—capabilities, culture, structure, and strategy.

At least one organizational structure issue was noted in the innovation studies. When I say “structures,” I mean the basic organizational framework, procedures, and resources employed to govern imaginative initiatives. The numerous approaches to innovation management and framework development present unique difficulties (Bogers et al., 2019). Only a fraction of the ideas individuals come up with will be put into action without the proper infrastructure, procedures, and communication routes (Koh et al., 2020).

This shows that there are many problems associated with effectively managing innovation (Hofmann & Jaeger-Erben, 2020). Leadership based on “command and control,” in which employees have little say in company affairs and mostly do tasks independently, is an example of restrictive innovation.

Reference List

Afriyie, S., Du, J. and Ibn Musah, A.-A. (2019) ‘Innovation and marketing performance of SME in an emerging economy: The moderating effect of transformational leadership,’ Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 9(1). Web.

Bogers, M. et al. (2019) ‘Strategic management of open innovation: a dynamic capabilities perspective,’ California Management Review, 62(1), pp. 77–94. Web.

Breier, M. et al. (2021) ‘The role of business model innovation in the hospitality industry during the COVID-19 crisis,’ International Journal of Hospitality Management, 92, p. 102723. Web.

Ceipek, R. et al. (2020) ‘Digital transformation through exploratory and exploitative internet of things innovations: the impact of family management and technological diversification*,’ Journal of Product Innovation Management, 38(1), pp. 142–165. Web.

Cichosz, M., Wallenburg, C.M. and Knemeyer, A.M. (2020) ‘Digital Transformation at Logistics Service Providers: Barriers, success factors and leading practices,’ The International Journal of Logistics Management, 31(2), pp. 209–238. Web.

Elmo, G.C. et al. (2020) ‘Sustainability in tourism as an innovation driver: an analysis of family business reality,’ Sustainability, 12(15), p. 6149. Web.

Gurzawska, A. (2019) ‘Towards responsible and sustainable supply chains – innovation, multi-stakeholder approach and governance,’ Philosophy of Management, 19(3), pp. 267–295. Web.

Hofmann, F. and Jaeger‐Erben, M. (2020) ‘Organizational transition management of circular business model innovations,’ Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(6), pp. 2770–2788. Web.

Koh, L., Dolgui, A. and Sarkis, J. (2020) ‘Blockchain in transport and Logistics – Paradigms and transitions,’ International Journal of Production Research, 58(7), pp. 2054–2062. Web.

Lee, J. et al. (2019) ‘Emerging technology and business model innovation: the case of artificial intelligence,’ Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 5(3), p. 44. Web.

Lee, Y.K. (2021) ‘Transformation of the innovative and sustainable supply chain with upcoming real-time fashion systems,’ Sustainability, 13(3), p. 1081. Web.

Marion, T.J. and Fixson, S.K. (2020) ‘The transformation of the innovation process: how digital tools are changing work, collaboration, and organizations in new product development*,’ Journal of Product Innovation Management, 38(1), pp. 192–215. Web.

Mendling, J., Pentland, B.T. and Recker, J. (2020) ‘Building a complementary agenda for Business Process Management and Digital Innovation,’ European Journal of Information Systems, 29(3), pp. 208–219. Web.

Pedersen, C.L., Ritter, T. and Di Benedetto, C.A. (2020) ‘Managing through a crisis: managerial implications for business-to-business firms,’ Industrial Marketing Management, 88, pp. 314–322. Web.

Peltokorpi, J. and Jaber, M.Y. (2022) ‘Interference-adjusted power learning curve model with forgetting,’ International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 88, p. 103257. Web.

Petzold, N., Landinez, L. and Baaken, T. (2019) ‘Disruptive innovation from a process view: a systematic literature review,” Creativity and Innovation Management, 28(2), pp. 157–174. Web.

Rampersad, G. (2020) ‘Robot will take your job: innovation for an ERA of artificial intelligence,’ Journal of Business Research, 116, pp. 68–74. Web.

Sjödin, D. et al. (2020) “An agile co-creation process for digital servitization: A micro-service Innovation Approach,” Journal of Business Research, 112, pp. 478–491. Web.

Soni, N. et al. (2020) ‘Artificial Intelligence in business: From research and innovation to market deployment,’ Procedia Computer Science, 167, pp. 2200–2210. Web.

Sun, G., Zhang, X. and Lin, Y. (2022) ‘Evaluation model of sports culture industry competitiveness based on fuzzy analysis algorithm,’ Mathematical Problems in Engineering, pp. 1–8. Web.

What is innovation? (2022) McKinsey & Company. Web.