Introduction

Atrial fibrillation is a supraventricular arrhythmia characterized by rapid and disordered depolarization of the atria, where integrated atrial contraction disappears and is replaced by irregular fibrillary atrial muscle twitching. In atrial fibrillation, there is accompanying irregular rapid ventricular contraction, and although paroxysms may occur, yet, mostly atrial fibrillation (AF) becomes a permanent condition (Scott, 1973). AF is the most prevalent arrhythmia seen in clinical practice. AF frequency increases with age, and based on population studies, AF prevalence is 5% among individuals 65 or older. Common causes and associated conditions include hypertension, cardiomyopathy, valvular heart disease (especially mitral stenosis), sick sinus syndrome, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome (especially in young patients), alcohol use (holiday heart), and thyrotoxicosis (Habermann and Ghosh 2008).

Atrial fibrillation has a distinct focal source or trigger. These focal points are in the cardiac muscle in the proximal parts of the pulmonary veins. Atrial fibrillation must be differentiated from atrial flutter (uniform flutter waves) and multifocal atrial tachycardia (isoelectric interval between premature atrial contractions that have three or more different morphologic forms). Patients with AF face risks of stroke and heart failure, and the dwindled quality of life because of either AF symptoms like fatigability and palpitations or the often associated cardiovascular diseases (Habermann and Ghosh 2008).

Epidemiology of atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation has been recognized as a distinct rhythm since the beginning of the 20th century. In clinical practice, AF is the most common suffered arrhythmia met, yet it remains one of the greatest challenges in heart rhythm disorders. Based on epidemiologic data; nearly 1% of individuals older than 60 years suffer from AF, increasing to more than 5% of individuals aged 65 to 70 years, with the rate of newly diagnosed AF nearly doubling with each decade (Go As et al 2001). Overall, one in four men and women after age 40 develop AF, falling only slightly to one in six in individuals without prior history of cardiac disease such as myocardial infarction (MI) or congestive heart failure (Llyod-Jones et al, 2004). Data from the Rochester Epidemiology Project are consistent with these findings. Further, data point to a significant increase in the age-adjusted prevalence of AF in patients with ischemic stroke when compared with age- and gender-matched controls and was observed both in males and females (Tsang et al 2003). In the United States this translates nearly to 2.3 million people affected by AF, a figure projected to increase to around 3.3 million by 2010 and 5.6 million by 2050. Added to this, the proportion of patients with AF older than 80 years is expected to exceed 50% by 2050 (Kannel and Benjamin 2008).

From the previous discussion, AF may represent a growing epidemic considering a possible underestimation of the prevalence of AF since nearly one third of episodes are asymptomatic. In the Canadian Registry of AF, 21% of patients with newly diagnosed AF were asymptomatic. Further, among untreated patients, asymptomatic episodes of AF are much more common than symptomatic episodes. Besides, in around one fifth of patients, asymptomatic episodes are documented before the onset of symptoms. Further evidence comes from analysis of data gained from permanent pacemaker interrogation, where in patients with a history of atrial fibrillation, up to one in six have silent episodes lasting 48 hours or more (Friberg et al 2003).

Atrial fibrillation also accounts for more than one third of arrhythmia-related hospitalizations in the United States, with more than 2 million hospital admissions in the U.S. over a 5-year period. Added to this is the frequent need for hospitalization, and emergency room visits, in particular, for direct current cardioversion and initiation of antiarrhythmic drug therapy complications as well as episodes of congestive heart failure exacerbation because of inadequately controlled AF. Based on the need for cardioversion, drug therapy, and anticoagulation, the estimated annual cost of treating patients with AF is around 22% higher than for patients without AF. This continues for several years after initial hospitalization. Thus, management of patients with AF imposes significant and continued socioeconomic burden (Khairallah 2004). In 2006, Heeringa et al conducted a retrospective study of a European population, which confirmed the mentioned figures pointing to the lifetime risks to develop AF was similar in European data to North American epidemiological data.

Etiology of atrial fibrillation

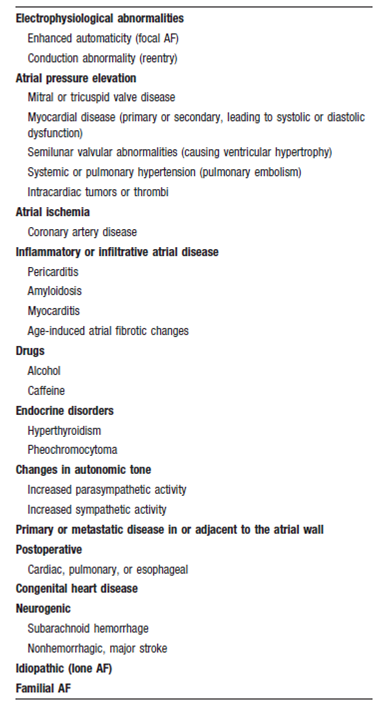

The frequency of AF in the population, its occurrence in those with and without cardiac disease, and its strong association with age suggest that there are many etiologies for this arrhythmia, which may share a common pathology and pathophysiology. Table 1 summarizes the etiological and risk factors that predispose to AF (Fuster et al 2006).

AF is associated with almost any type of underlying heart disease that causes changes of the atrial myocardium, including distention, inflammation, hypertrophy, ischemia, fibrosis, and infiltration. Additionally, there are normal age-related changes of the myocardium, including amyloid deposits and fibrosis, perhaps accounting for the increased incidence of AF in the elderly. Parasympathetic or sympathetic nervous system inputs alter atrial electrophysiological properties and can provoke AF. Systemic infections, pulmonary disease and infections, pulmonary embolism, hyperthyroidism, and certain toxins or metabolic abnormalities may promote AF even in the absence of underlying atrial disease. In up to 15% of cases, there is no structural heart disease and no identifiable cause for the arrhythmia; this has been termed lone AF. Several autopsy studies have reported that the most common cardiac diseases associated with AF are coronary artery disease with or without a prior myocardial infarction, rheumatic heart disease, and hypertensive heart disease. However, clinical observation has emphasized that when AF occurs in those with coronary artery disease, left ventricular dysfunction or heart failure is usually present. Currently the most common underlying abnormalities associated with either intermittent or permanent AF are hypertensive heart disease, which increased the risk of AF almost 5-fold and 9-fold in men and women, respectively. Heart failure of any etiology increases the risk by over 4-fold and 14-fold in men and women, respectively (Kowey and Naccarelli 2005). Thus, for the case at hand a diagnosis priority should focus on the coexistence of hypertension, ischaemic heart disease, or heart failure. Other causes should also be looked because understanding of the interrelationship of etiological factors and the disease presentation and possible progression helps in tailoring an effective management plan (Conen et al 2009).

Pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation (Mechanisms)

The pathophysiology of AF is complex and inadequately understood. The association of AF with diverse cardiac diseases such as ischemia, valvular disease, and cardiomyopathy implies a common mechanism leading to secondary AF and is supported by the finding in many cases of pathologic changes within the atria beyond that associated with the underlying cardiac disease. Fibrillation of the atria leading to the clinical syndrome of AF may represent a final common pathway for several different mechanisms rather than any one distinct disease in and of itself, and more than one mechanism may underlie AF in the same individual (Brady and Gersh 2007).

Histological examination of human atria in patients with AF reveals evidence of patchy fibrosis and fatty infiltration changes consistent with an inflammatory response along with atrial myocytes hypertrophy. Prolonged AF is associated with atrial dilatation and atrial mechanical dysfunction, a process termed structural remodeling. Restoration of normal sinus rhythm links to reversal of these changes and therefore, normalization of atrial function (Falk 2001).

Electrophysiologically, evidence of enhanced automaticity or micro-reentry within the atria (the so-called multiple wavelet hypothesis) is thought to be important. Repeated episodes of atrial fibrillation cause shortening of the atrial refractory period and loss of normal lengthening of atrial refractoriness at slower heart rates, allowing reentry within the atrial tissue. This process has been termed electrical remodeling and is also reversible following restoration of normal rhythm. Increased automaticity within thoracic veins may be an important mechanism in paroxysmal forms of AF, whereas micro-reentry may be more important in persistent or permanent forms of AF. Another important concept is the notion that “AF begets AF.” Specifically, prolonged or recurrent episodes of AF appear to promote both electrical and structural changes within the atria (remodeling), further promoting the likelihood of recurrent AF episodes (Rostock et al 2008).

The role of structural changes occurring within the atria in the pathogenesis of AF is underscored by recent evidence that agents that decrease the progression of fibrosis, such as angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, appear to also reduce progression of AF. Similarly, in experimental models of tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy, ACE and AT-1 receptor blockers reduce the extent of interstitial fibrosis and also the inducibility of AF (Brady and Gersh 2007).

The importance of atrial dilation in the pathophysiology of AF has also been recognized, and left atrial volume along with diastolic dysfunction are important predictors of AF occurrence in the elderly. Gersh et al (2005) assumed that atrial stretch may lead to activation of specific stretch-activated ion channels, promoting cellular depolarization and rapid firing from foci, perhaps within the thoracic veins. Prolonged or recurrent activation of atrial myocardium in this way, as a consequence, may promote structural and electrical remodeling, in turn promoting occurrence of AF (Gersh et al 2005). The concept of multiple modulating factors that initiate or help to maintain AF was explained by Shiroshita-Takeshita et al 2005where the modulating factors know to play a role in initiating and maintaining AF are summarized in figure 1.

Diagnosis of atrial fibrillation

In addition to the patient’s medical history, which may suggest an etiological diagnosis, social history including tobacco, alcohol or other drugs used should be in mind. History suggestive for increased risk of thrombo-embolic like long periods of immobilization, or history of transient ischemic attacks should be sought for. Symptoms of complications like dyspnea related to heart failure or symptoms related to ischemic heart disease are important to trace. Although many cases may be asymptomatic symptoms like fatigability may develop as a result of hemodynamic dysfunction, other symptoms like palpitations may arise because of lost synchronous atrial activity, or the rapid heart rate. The diagnosis of AF needs to be confirmed by ECG either surface or portable like portable Holter ECG in cases of paroxysmal AF. ECG characteristically displays the irregularly irregular narrow QRS complex, besides the absence of p wave, which represents atrial depolarization (Crijns et al 2009).

Further investigations include cardiac imaging, which include a chest x-ray for signs of dilated heart or altered pulmonary vascular markings (Crijns et al, 2009). Imaging techniques like CT and magnetic resonance angiography have produced more accurate measurement of cardiac anatomy. However, echocardiography has an important use in assessing cardiac structure and function, in addition to patients’ risk stratification. Intracardiac echocardiography has allowed real-time guidance of interventions like radiofrequency ablation in patients with AF. Trans-esophageal echocardiography has allowed cardioversion (electric shock applied to the heart to convert abnormal rhythm to a normal one) (Wazni et al 2006).

Complications of atrial fibrillation

Stroke is a cause of significant morbidity and mortality in patients with AF and may be the first presenting symptom in up to 25%. The pathogenesis of thrombo-embolism in AF is complex and in many individuals is multifactorial. Close to one quarter of AF-associated stroke is thought to be a consequence of intrinsic cardiac disease such as atheroma (especially within the proximal aorta) and hypertension. Risk factors for stroke in patients with AF include prior thrombo-embolic stroke, which is the most powerful risk factor for subsequent stroke, with a rate of 10% to 12% per year, CHF, hypertension, increasing age, and diabetes mellitus. Female gender and systolic blood pressure >160 mm Hg and left ventricular dysfunction have also been associated with increased risk of stroke. Increased age is also an important risk factor, with almost half of AF-associated strokes being observed in persons older than 75 years and is the most frequent cause of disabling stroke in elderly women. In addition, elderly persons are at greater risk of anticoagulant–related bleeding complications. Echocardiographic data suggest that thrombus arises most frequently within the left atrial appendage (LAA) and is most readily visualized using trans-esophageal echocardiography (Wyse and Gersh 2004).

A grave risk in AF patients is increased incidence of death. In patients aged 55 to 94 years, death occurred in 61.5% of men compared to 30% in men of the same age group without AF. In females the rates were 58% and 21% respectively. The cause of this increased death rate links mainly to stroke (Reimold, 1999).

Management of atrial fibrillation

Given the data of the case at hand, it is clear the patient is a newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation case, with no known underlying risk factor, palpitations and fatigability indicate disturbed heart rate cardiac rhythm, hemodynamic disturbances with a possibility to develop thrombo-embolic complication. In such a case, treatment strategy aims at controlling heart rate, correcting disturbed rhythm and prevention of thrombo-embolic manifestations (Fuster et al 2006). Rhythm control strategy aims at restoring and maintaining the cardiac rhythm, it has the advantages of relieving the symptoms, improving fatigability and hemodynamic functions, less need to anticoagulant therapy, and prevention of tachycardia induced cardiomyopathy. However, it has the disadvantages of common occurrence of major cardiovascular events like ischemia or thrombo-embolism with greater rates of prolonged hospitalization. Rate control strategy aims at controlling the ventricular heart rate with no obligation to cardiac rhythm has the benefits of being more effective in maintaining rate control, and greater cost effectiveness. It is not usually an option for a first presentation of AF like the case at hand (Lim et al 2004).

β adrenergic blocking agents and calcium channel blocker have replaced digoxin as rate controlling agents because of their improved rate control results. Digoxin is still useful in combination when β adrenergic or calcium channel blockers are not tolerated. Occasionally, especially in older patients, the ventricular rate is intrinsically controlled so no atrioventricular blocking agents is useful. In this case a pacemaker may be necessary to control the heart rate (Page 2004). Nearly 72% of newly diagnosed AF patients regain cardiac rhythm spontaneously. The remaining patient can be treated with antiarrhythmic drugs like procainamide, quinidine, propafenone, amiodarone and other agents to achieve medical cardioversion. However, the risk of thrombo-embolic complication remains high and long term rhythm control results are poor (20 to 30%). In these cases atrioventricular node ablation in conjunction with permanent pacemaker implantation or direct-current cardioversion may be indicated (Abusaada et al 2004).

Treatment to prevent thrombo-embolic complication is individually tailored and need assessment of the patient’s risk, treatment benefit, assessing the risk of major hemorrhage, and the patient preference. Generally treatment choice is either anticoagulant therapy as warfarin or antiplatelet therapy as aspirin. In AF cases complicating valvular heart disease, the risk of thrombo-embolism is much higher (up to 17 folds), in these cases, warfarin is indicated. The choice is more difficult in non-valvular cases; warfarin reduces the stroke risk by nearly 62%, while aspirin shows 22% relative risk reduction. It should be noted that stroke risk does not differ significantly in paroxysmal AF patients than persistent or permanent AF patients (Medi et al 2007). Thus, the patient in this case study should receive either warfarin or aspirin depending on post-admission assessment data.

Management of an AF patient: A nursing perspective

The case studied is an acute case of AF, therefore nurse monitoring is of utmost importance and should primarily focus on:

- Hemodynamics monitoring. The primary function of the cardiovascular system is to ensure infusion (cell supply) and removal of wastes (CO2 and metabolites). Therefore, hemodynamic monitoring aims to indicate proper infusion via observation of pulse, blood pressure, and fluid input and output (Ward 2008).

- ECG monitoring. Since AF can be life threatening, the nurse’s duty in ECG monitoring is to identify the type of arrhythmia, identify the probable cause from patient’s history, and develop good baseline knowledge on management modalities. In monitoring a patient’s ECG, the CCU nurse should keep in mind the key stages of normal cardiac conduction namely; atrial changes are reflected in P wave, atrioventricular node rhythm, changes reflect in the PR-interval and ventricular changes reflect in the QRS complex, ST segment, and T wave (Woodrow 2006).

- Monitoring of medications’ side effects. Like bradycardia, nausea and vomiting for digitalis toxicity, hypotension and heart block for most β blocking agents, and hypotension with prolongation of QT interval for antiarrhythmic drugs. Bleeding tendencies as a complication of anticoagulant therapy should also be monitored (Abusaada et al 2004).

- Stroke monitoring. Characteristically, there are no biomarkers for early prediction of stroke risk; therefore, accurate information stemming from close patient monitoring is important (Montaner 2008). In this respect a CCU nurse should always keep in mind that previous history of stroke or transient ischemic attacks (TIA) are the strongest independent predictors of stroke in AF patients over 60 years (Fuster et al 2006).

Nursing intervention

In acute AF cases, the following nursing diagnosis needs intervention, patient’s fear and anxiety, which may obstruct patient’s contribution to care regimens. This should be managed by evaluating the patient’s coping and helping the patient to identify and understand the health problem. Second, in the case at hand, the patient’s fatigability and decreased tolerance to effort needs evaluation of the cardiac status before effort, evaluation of exacerbations or persistence of the condition and proper documentation of tolerance to activity. The patient at hand has some degree of decreased cardiac output as manifested by fatigability, therefore, further symptoms indicating decrease cardiac output like ischemic pain, decreased blood pressure, and dyspnea should alert the CCU nurse for further intervention (Prudente 2008).

Patient teaching remains an essential part of the CCU nurse, the hazards of smoking, alcohol intake and obesity should be clarified to the patient. Further, a brief knowledge on the significance of the patient’s symptoms of palpitation and fatigability, besides alarming symptoms that mandate medical attention like dyspnea should be briefed as well (Rocca 2007).

Conclusion

Atrial fibrillation is the commonest cardiac arrhythmia. A nurse’s knowledge of AF and its management assists improving the patient’s quality of life, and saving the patient possible grave complications. In many cases, the nurse is the first member of the medical faculty to recognize AF; thus the more knowledge a nurse get, the more will be prepared to provide maximum care.

References

Abusaada, K., Sharma, S., B., Jaladi, R., et al (2004). Epidemiology and Management of New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation. Am J Manag Care, 10 (Supplement), S50-S57.

Brady, P., A., and Gersh, B., J (2007). Atrial Fibrillation and Flutter (chapter 92), in Cardiovascular Medicine (Third Edition). Willerson, J., T., Cohn, J., N., Wellens, J., J., and Holmes, D., R (Editors). London: Springer-Verlag Ltd.

Crijns, H., J., G., M., Allessie, M., A., and Lip, G., Y., H. (2009). Arial Fibrillation: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis and Diagnosis (chapter 29), in The ESC Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. Camm, A., J., Luscher, T., F., and Serruys, P., W (Editors). New York: Oxford University Press.

Go As, Hylek, E., M., Philips, K. A., et al (2001). Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the Anticoagulation and risk factors In Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA, 285, 2370-2375.

Gersh, B., J., Tsang, T., S., M., Barnes, M., E., and Seward, J., B (2005). The changing epidemiology of non-valvular atrial fibrillation: the role of novel risk factors. European Heart Journal, 7 (Supplement C), C5-C11.

Conen, D., Osswald, S., and Albert, C., M (2009). Epidemiology of atrial fibrillation. Swiss Med Wkly, 139, 346-352.

Falk, R., H (2001). Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med, 344(14), 1067-1078.

Friberg, J., Scharling, H., Gadsboll, N., and Jensen, G. B (2003). Sex-specific increase in the prevalence of atrial fibrillation (the Copenhagen City Heart Study). Am Heart J, 92, 1419-1423.

Fuster, V., Ryden, L., E., Cannom, D., S. et al (2006). ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines. Circulation, 114, e257-e354.

Habermann, T., M. and Ghosh, A. K (2008). Mayo Clinic Internal Medicine Concise Textbook. Rochester, MN: Mayo Clinic Scientific Press Informa Healthcare.

Heeringa, J., Deirdre, A., M., van der Kuip, et al (2006). Prevalence, incidence and lifetime risk of atrial fibrillation: the Rotterdam study. European Heart Journal, 27, 949-953.

Kannel, W., B. and Benjamin, E. J (2008). Final Draft Status of the Epidemiology of Atrial Fibrillation. Med Clin North Am, 92(1), 17-41.

Khairallah, F., Ezzedine, R., Ganz, L., I. et al (2004). Epidemiology and determinants of outcome of admissions for atrial fibrillation in the United States from 1996 to 2001. Am J Cardiol, 94, 500-504.

Kowey, P., and Naccarelli, G., V. (2005). Atrial Fibrillation. New York: Marcel Dekker.

Lim, H., S., Hamaad, A., Lip, G., YH (2004). Clinical review: Clinical management of atrial fibrillation – rate control versus rhythm control. Critical Care, 8, 271-279.

Lloyd-Jones, D., M., Wang T., J., Leip, E. P. et al (2004). Lifetime risk for development of atrial fibrillation: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation, 110, 1042-1046.

Medi, C., Hankey, G., J., and Freedman, S., B (2007). Atrial fibrillation. MJA, 186(4), 197-202.

Montaner, J., Perea-Gainza M., Delgado, P., et al (2008). Etiologic Diagnosis of Ischemic Stroke Subtypes With Plasma Biomarkers. Stroke, 39, 2280-2287.

Page, R., L (2004). Newly Diagnosed Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med, 351(123), 2408-2416.

Prudente, L., A. (2008). Quelling atrial chaos: Current approaches to managing atrial fibrillation. American Nurse Today, 3(8), 21-25.

Reimold, S., C. (1999). Arial fibrillation: current epidemiology, noninvasive imaging, and pharmacologic therapy. Cardiology Rounds, 3(4), 1-6.

Rocca, J., D (2007). Responding to atrial fibrillation. Nursing, 37(4), 37-41.

Rostock, T., Steven, D., Lutomsky, B., et al (2008). Atrial Fibrillation Begets Atrial Fibrillation in the Pulmonary Veins. J Am Coll Cardiol, 51(22), 2153-2160.

Scott, R., B. (Sir) (1973). Price’s Textbook of the Practice of Medicine (11th edition). London: Oxford University Press.

Shiroshita-Takeshita, A., Brundel, B., J., J., M., and Nattel, S (2005). Atrial Fibrillation: Basic Mechanisms, Remodeling, and Triggers. Journal of Interventional Cardiac Electrophysiology, 13, 181-193.

Tsang, T., S., M., Petty, G., W., Barnes, M., et al (2003). The prevalence of atrial fibrillation in incident stroke cases and matched population controls in Rochester, Minnesota. J Am Coll Cardiol, 42, 93-100.

Ward, M. (2008). Define Quality Measure Before They Define You. on the pulse, 20(4), 1-18.

Wazni, O., M., Tsao, H-M., Chen, S-A., et al (2006). Cardiovascular Imaging in the Management of Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol, 48, 2077-2084.

Woodrow, P. (2006). Intensive Care Nursing A framework for practice (Second edition). New York: Routledge.

Wyse, D., G. and Gersh, B. J (2004). Atrial fibrillation: a perspective: thinking inside and outside the box. Circulation, 109, 3089-3095.