This exhibition’s theme is Biblical art, a concept about the sacred Christian work utilizing imagery and characters from the Bible or the Scriptures. Notably, in some cases, Biblical art contains stories from legends whose figures are from the Bible, but the story itself may not be part of the Scriptures or the Apocryphal Gospels. In the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the Catholic Church’s heads commissioned artists to produce visual art to decorate the chapels and cathedrals. For this reason, these forms of artistic expression were popular in Europe, where Roman Catholicism thrived. In the past, artists used paintings, sculptures, mosaics, and stained glass to illustrate scenes from the Bible and help convey specific messages, especially during the era of reduced literacy (Lumen). As is the norm in human evolution, Biblical art also underwent significant changes over the years, representing greater artistic expression and the metamorphosis of the consumers’ needs over time.

This exhibition contains a collection of six items of the European visual culture derived from two historical periods. The first three items are insular works of art from the Middle Ages, while the last three are from the Renaissance period. All the visual art items included in this presentation remain related in that all of them are examples of Biblical art pieces. Any differences between them may be due to changes in art production techniques used at various times. For instance, insular art existed mainly in post-Roman Britain and Ireland. Its main characteristic is the remarkable fusion of different cultures and traditions due to the travels of ecclesiastics and their craftspeople (Grove Art Online). Renaissance art’s characteristics include individualism, secularism, and classism, among others. They had fewer church paintings and tended to show individual rather than group faces. Audience would want to see this exhibition to appreciate Biblical art and its evolution.

Items from the Middle Ages

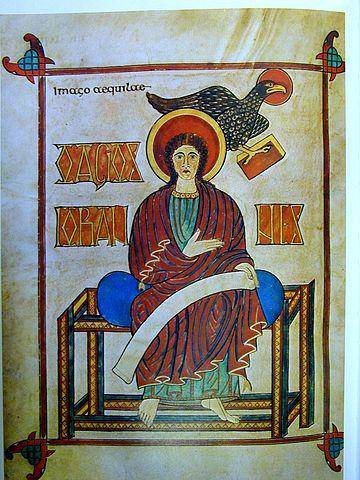

Figure 1 is a page from one of the four books of the Lindisfarne Gospels depicting John the Evangelist. It is collored ink on a flat vellum measuring 160 by 130 mm. The picture is stylized in keeping with the common practice of Biblical art in the Middle Ages. John the Evangelist here is wearing a piece of clothing that seems not to acknowledge the body beneath. He is also sited on a bench that does not ebb practically into the space behind him. Notably, a specific symbol represented each of the four Evangelists, and John’s emblem – an eagle – is drawn above his head carrying the Gospel, signifying the Second Coming of Jesus Crist. The artist who produced the figure kept modeling to a minimum such that it bears a close resemblance to the illustration of the other books in this collection. It is related to Figure 2 in the sense that both are parts of the illuminated manuscript Gospel book from the monastery at Lindisfarne, an excellent example of the unique insular art style, combining Anglo-Saxon, Mediterranean, and Celtic elements into one. As a component of the illuminated Gospel texts of the Middle Ages, this painting conveys a vital piece of information about the spread of Christianity back then. Notably, a decline in literacy at the time meant that only monks and nuns could access printed material (Kearney). Significantly, they copied these illustrated manuscripts and, in the process, created art that became the standard method of communicating Biblical narratives.

Figure 2 is the title page of the Gospel according to St. physically, it is collored ink on vellum measuring 160 by 130 mm. John in the Book of Kells. It depicts the thoughtful-looking Evangelist on the page’s top, suggesting that the apostle understood his mission’s weight and wondered how best to deliver salvation to the world. The picture also shows a less moral character swinging from a goblet of wine, suggesting that the Gospel is meant to redeem the lost. The page also contains Latin inscriptions and descriptive and prefatory matter decorated with several colorful illuminations and illustrations. Figure 2 is related to Figure 3 in that they are both examples of illustrated manuscripts. Typically, illuminated manuscripts, sculptures, mosaics, metalwork, and stained glass have had higher survival rates than works on tapestry and fresco wall paintings (Kearney). Celtic monks who once inhabited the remote Scottish island of Kells in County Meath may have produced the ornately illustrated Book of Kells around 800 C.E. People describe the Book of Kells as Western illumination and calligraphy’s zenith due to its lavish decoration. The monks believed to have created the Book of Kells inhabited a monastery in County Meath founded by the Irish monk Columba. The monks and nuns who created the art piece may have utilized 185 calves’ skins for the project (Kearney). In one way or another, the monks also decorated all the 680 pages of the Book of Kells.

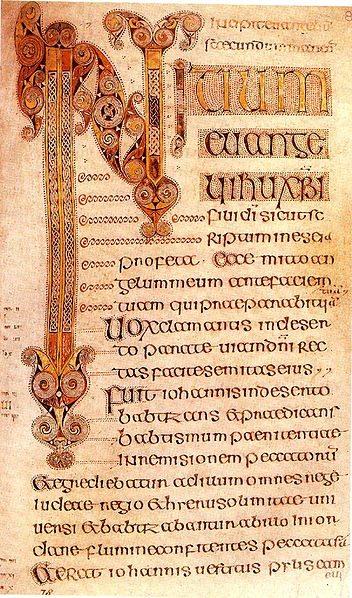

Figure 3 alongside is the decorated first page of the Vulgate translation of the Book of Mark (one of the four Gospels) by Saint Jerome of Stridon. It is a parchment codex measuring 180 by 120 mm with titles in rustic capitals. It is part of the oldest extant Gospel book, predating, for example, the Book of Kells, by one hundred years. It is a fine example of the 7th century’s Biblical art. The page features words written in common Latin (Vulgate Latin). The Pope had only requested Jerome to translate the Gospels, but Jerome extended the translation to include most books of the Bible. Thus, it utilizes everyday Latin diction and writing style from the fourth century, contrasting sharply with the more elegant and formal Cicero Latin. For over one thousand years, Jerome’s Translation of the Bible served as the standard version used by Christians in the west (British Library). Notably, scholars have not reached a consensus regarding the exact location of the Book of Durrow’s production (Visual Arts). They continue the debate on the book’s possible origin to this day, with most of them believing it could be Ireland’s Durrow Abbey, Western Scotland’s Iona Abbey, or a monastery in Northumbria (possibly the one in Lindisfarne). Notably, Jerome’s translation into Vulgate of the four Gospels represents his revision of a Vetus Latina translation he had completed earlier. At the Council of Trent between the Catholic Church designated the Vulgate translation as the official Latin version.

Items from the Renaissance

Figure 4 depicting Mary the Virgin’s Marriage, is a 185 by 234 cm painting that is in good condition done by Raphael. It is reminiscent of a Perugino altarpiece of the same subject (see Figure 5). The Italian artist completed the oil on panel painting in 1504 for a church in his country’s Citta di Castello region. It depicts Saint Joseph and the Virgin Mary’s marriage, with a church building visible in the background (Totally History). A high priest – richly attired – clasps Mary and Joseph’s hands in the foreground as the groom prepares to put a ring on the bride’s finger. A group of soft-eyed women – perhaps the bride’s maids, stand behind Mary, with their attire being only a little less extravagant than the Priest’s. At the far left, still in the foreground, a girl in red looks at the viewer wistfully. A group of disappointed suitors stands behind Joseph. The one with red pants next to Joseph breaks his wand with his knee, probably as a sign of resignation from chasing Mary. Behind him is another sad fellow who has bent his rod as well. Of the suitors, Joseph is the only one barefooted and with a beard. According to the legend upon which the artist based this painting, a high priest gave each potential suitor of the Davidic line a rod to place on the altar to determine who was favored enough to win Mary’s hand in marriage. As seen in this picture, only Joseph’s rod flowered, while the other suitors’ did not. For this reason, the artist depicts them breaking their sticks in frustration and disappointment for not having the favor to marry Mary.

Figure 5 also depicts the Virgin Mary’s marriage to Saint Joseph. The art measures 185 by 234 cm and is in good condition. It is related to Figure 4 (above) in that it inspired Raphael to create a similar for a church in Italy’sItaly’s Citta di Castello. Most scholars believe Perugino, the Italian Renaissance master, did this painting. However, some later historians attribute it to Perugino’s student, Lo Spagna. Further, scholars believe Perugino took over the commission of the artwork from Pinturicchio (Brewminate). The contract was about creating an altarpiece for the recently completed Chapel of the Holy Lamb in the cathedral of Perugia, work that ended between 1500 and 1504, perhaps after several periods of stasis (Traveling Tuscany). The painting contains almost every attribute that Raphael captured in his later treatment of the matter. Additionally, it displays prominently Mary’s engagement ring, which the cathedral at Perugia kept as a holy relic. Napoleon is believed to have stolen the painting and took it to Normandy in 1797. The painting depicts Joseph and Mary the Virgin’s elegant wedding conducted by a fabulously dressed priest. A group of women stands behind Mary wearing the traditional red gown and blue cloak. Mary is also wearing the same red and blue outfit but has her hair held by gauzy veils. Joseph, the groom, adorns something similar to a priest’spriest’s cassock with a cloak graciously draped around him. Some people believe that Joseph was much older than Mary and that he was a widower during their wedding. In the background, there are several disappointed suitors, including the unmistakable man breaking his walking stick on his knee.

Figure 6 is a self-portrait of Pietro Perugino completed between 1497 and 1500. It is Tempera on wood measuring 57 cm by 42 cm. Other physical characteristis include fading and worn out ages. Other than that, the portrait is in perfect condition requiring no restoration. A student of Fiorenzo di Lorenzo and Piero Della Francesca, Perugino influenced many artists, including Raphael, his student. Perugino studied at Arezzo and was a fellow pupil of Lorenzo di Credi and Leonardo da Vinci in Verrocchio’s Florence studio. Pope Sixtus IV summoned Perugino and other artists to Rome in 1479 to help decorate the Sistine Chapel (Sun Bird Arts). The Pope appointed him the team leader, whose other members were Sandro Botticelli, Cosimo Rosselli, and Domenico Ghirlandaio. As evidenced by his various paintings, including the “Christ Handing the Keys to St. Peter” one, order, simplicity, and clarity characterized his works. Unfortunately, in later years, officials destroyed some of his works to create room for Michelangelo’s Last Judgement. Born in 1446 or thereabout to Cristoforo Marie Vannucci, he developed some of the artistic qualities and characteristics that found significant expression during the High Renaissance period. His self-portrait is simple and straightforward, depicting the face of a middle-aged man with a black top and a red beret. Perugino may have been in his late 40s or early 50s by this portrait’s completion. Perugino died in 1523 in his early 70s according to his accomplices, Vasari and Giovanni Santi (Artsy). He is best remembered for his “Marriage of the Virgin” painting, which is based on a popular legend (rather than a Biblical story), positing that many people wanted to marry the Virgin Mary. The priest gave every suitor of the Davidic line a dry rod to place on the altar, and only Joseph’s flowered.

Works Cited

Artsy. Pietro Perugino: The marriage of the Virgin Mary, n.d. Web.

Brewminate. The Art and Architecture of Early Medieval Europe, 2018. Web.

British Library. The Harley Gospels: an early surviving example of St Jerome’s Vulgate, n.d. Web.

Grove Art Online. Insular art, n.d. Web.

Kearney, Martha. The Book of Kells: Medieval Europe’s greatest treasure? BBC Culture, 2016, Web.

Lumen. The Early Middle Ages, n.d. Web.

Sun Bird Arts. Self-portrait, 1497–1500, n.d., Web.

Totally History. The Marriage of the Virgin, n.d., Web.

Traveling Tuscany. Pietro Perugino: Marriage of the Virgin, n.d., Web.

Visual Arts. Book of Durrow, n.d. Web.