Introduction

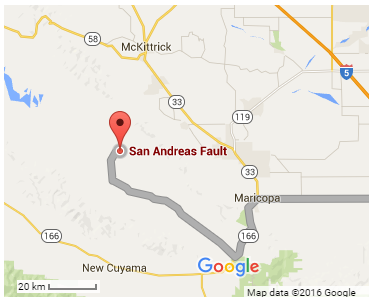

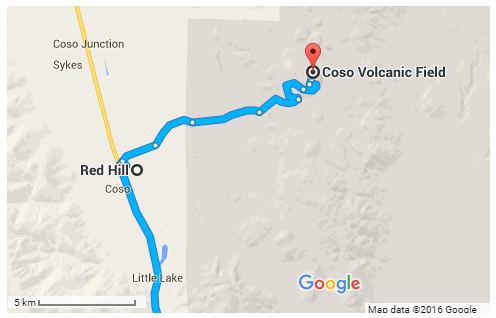

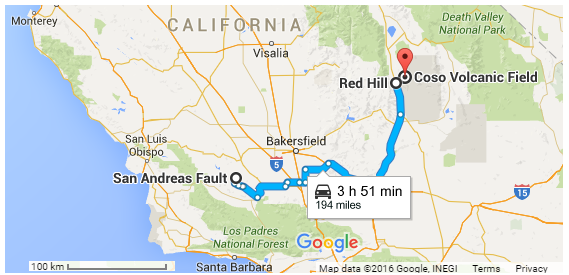

Since Hawaii State is located in the middle of the Pacific Plate, we will have to leave the Island of Maui to see a plate boundary feature. This part of the trip will be devoted to the geological features of California, US. First, we will visit the section of the San Andreas Fault that is located in San Luis Obispo County (see fig. 1). Then, we will move towards the fifth stop, Coso Volcanic Field that is located in Inyo County (see fig. 3). The Field is seismically active, which makes it an earthquake feature. We will not venture far and only get to the Red Hill Mountain (see fig. 2). Maricopa, CA can be regarded as the place where we can rest and eat (see fig. 1).

San Andreas Fault, San Luis Obispo County

The San Andreas Fault is situated on the boundary between the Pacific and North American plates. It is 1100 kilometers long (without taking into account the curves) and 20 million years old (Schulz & Wallace, 2013). As a result, it is a mass or a line of smaller faults rather than a single one (National Part Service, 2016). Apart from that, it is parallel with other major faults, for instance, the Hayward Fault.

The San Andreas Fault is an example of a geological feature that appears as a result of transform fault boundary movement (Lutgens, Tarbuck, & Tasa, 2012). This kind of boundary is characterized by two plates sliding against each other horizontally, and a transform fault is a typical outcome of such movement. The result is the specific landscape: a “linear trough” with a similarly linear arrangement of features like valleys, “straight escarpments, and narrow ridges” (Schulz & Wallace, 2013, para. 4). This Fault is especially interesting since it is located on land instead of the ocean, which makes it easier to study (Lynch, 2013).

Being a transform fault, the San Andreas Fault is not shaken by earthquakes as severely as convergent boundaries (Lynch, 2013). The movement of the plates has a speed of 3.5-5 centimeters per year, but occasionally the process hurries up, and earthquakes change the landscape of the feature (National Part Service, 2016). For example, in 1857, the 7.9-magnitude Fort Tejon earthquake took place in the Carrizo Plain, and the fault moved 9 meters (Schulz & Wallace, 2013).

Similarly, in 1906, the great San Francisco Earthquake took place, with the biggest displacement amounting to 7.5 meters (National Part Service, 2016). Seismic activity is a natural consequence of the movement of plates that slip, break, scrape, and emit seismic waves. However, the Fault is in the state of a “seismic gap” right now: it has not been demonstrating significant seismic activity for several decades (Schulz & Wallace, 2013).

The Fault is a great source of information on earthquakes, but it is also admittedly a great danger to the resources and lives of the people of California (Schulz & Wallace, 2013). Naturally, the processes related to the boundary movement have also created the landscape, which can be regarded as a tourist attraction (USGS, 2016b). Still, the Fault is of greater interest for researchers than entrepreneurs. However, the geological activity in the region has produced more economically attractive spots, and our next stop is one of them.

Coso Volcanic Field, Inyo County

The Coso Volcanic Field is a group of red hills, “rhyolitic lava domes and basaltic cinder cones covering a 400 square kilometers of area” (Global Volcanism Program, 2013). The volcanoes are not currently active, but the seismic activity of the region is one of the most noticeable in the US (Schoenball, Davatzes, & Glen, 2015, p. 6221). The landscape was formed by eruptions that took place during the last quarter of million of years (USGS, 2016b).

Coso Field also features thermal waters that have been used as an energy source. As a result, its earthquakes can be caused by natural reasons (the active tectonics that is affected by the previous feature, the San Andreas Fault) and human activities (geothermal power production) (Schoenball et al., 2015).

Earthquakes are measured with the help of special tools called seismographs that produce seismograms. The magnitude of the earthquake is defined with a seismogram and measured with a suitable scale. For example, the moment magnitude applies to any earthquake but is challenging to compute. The famous “Richter” scale is easier, but it is best suitable for medium-magnitude earthquakes (Schulz & Wallace, 2013).

For the time being, scientists cannot predict the time of an earthquake. However, the tectonics of a region can suggest the possible place that needs to be monitored, and the aftershocks are predictable. Also, it is suggested that scientists will have more sensitive tools that will be able to predict earthquakes in the future completely (Lutgens et al., 2012; USGS, 2005).

Coso Volcanic Field is quite active. The earthquake of a magnitude of above 4 last happened in 1992 and was a part of a seismic swarm, a series of earthquakes (Global Volcanism Program, 2013). However, less than a month ago (on April, 12) a 3.1-magnitude earthquake took place in the region (USGS, 2016c). Moreover, over the past seven days, there were several earthquakes with a magnitude below 2.5 (USGS, 2016). No one lives on the Field, and only 370 people live within the 10 km radius of the area (Global Volcanism Program, 2013). As a result, earthquakes pose a lesser threat. Still, the region is being monitored by the U.S. Geological Survey through the Coso Microearthquake Network to ensure collecting and providing timely information on the current state of events (USGS, 2016a).

References

Global Volcanism Program. (2013). Coso Volcanic Field. Web.

Lutgens, F., Tarbuck, E., & Tasa, D. (2012). Essentials of geology (11th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Lynch, D.K. (2013). San Andreas Fault Information. Web.

National Part Service. (2016). Geologic Activity. Web.

Schoenball, M., Davatzes, N., & Glen, J. (2015). Differentiating induced and natural seismicity using space-time-magnitude statistics applied to the Coso Geothermal field. Geophysical Research Abstracts, 42(15), 6221-6228. Web.

Schulz, S., & Wallace, R. (2013). The San Andreas Fault. Web.

USGS. (2005). Earthquake Science Explained. Web.

USGS. (2016). 7 Days, All Magnitudes Worldwide. Web.

USGS. (2016a). Advanced National Seismic System. Web.

USGS. (2016b). Coso Volcanic Field: California Volcano Observatory. Web.

USGS. (2016c). M3.1 – 26km E of Coso Junction, CA. Web.

Maps