Introduction

The Arctic region is a common feature in discourses touching on Canada’s self-governance. As renewed focus on the Arctic region emerges, incursions into the region raises questions on Canada’s sovereignty claims. The Arctic region has attracted increased interest from several countries, despite differences inherent in international law. According to Andrea (774), the Arctic Council allows involved states to cooperate in developing the region responsibly.

Indeed, the Arctic region has attracted increased interest over the past decades because of the environment’s sensitivity to disturbances. The sensitivity is associated with the recent climate change, technological advancements, and commerce that is developing significantly in the region. In relation to climate change, the rising temperatures are melting glaciers and sea ice at extremely higher rates. This has created a shift in the efforts of the Council towards slowing the change, to protect both plant and animal life (“Arctic Climate Impact Assessment” par. 3).

On the other hand, the melting ice is facilitating the exploitation of new opportunities using technological advancements. The opportunities resulting from the exploitation of the Arctic’s resources are opening up new transport routes in the region. Despite this increasing interest, “Arctic Climate Impact Assessment” (par. 3) states that these developments deserve better management, for the region’s benefit. For the Arctic’s inhabitants, the developments carry advantages and disadvantages that may create desired and undesired side effects if not managed carefully.

Clearly, the changing climate will affect the lives of indigenous traditionalists, while the business community will create prospects that may offer better lives for inhabitants. Despite the challenges facing the Arctic, the region has cooperated with the Arctic states with minimal conflicts and consensus (“Arctic Climate Impact Assessment” par. 3). The Council has stepped in to prioritize on promoting sustainable environmental development. The Council also strives to foster the positive cooperation between the indigenous people and the neighboring states. With this, the relationship between the Arctic systems and other global processes deserve keen interest, if the region is to handle the problems arising in the international society.

What is the Circumpolar North?

The circumpolar north covers the Arctic Region and all countries forming a ring around the North Pole. The circumpolar north has undertaken a series of international cooperation efforts meant to device effective governance systems that are capable of handling the arising issues in the Arctic (“Arctic Council – the venue for Arctic decision-making” par. 12). Although international cooperation efforts in the early nineties may seem few, one cannot ignore their significance.

The Arctic region has attracted various international development initiatives, which have set institutions that govern social, economic and political practices within the region. In addition, various institutional arrangements have cropped up to advance the causes of involved states in various policy concerns (“Arctic Council – the venue for Arctic decision-making” par. 12). While the recent Arctic initiatives may seem to cover only the northern regions, the circumpolar north has engaged in numerous multilateral initiatives. The Arctic Council has significantly raised consciousness of the distinct nature of the region, in addition to increasing the region’s awareness on various environmental concerns (“Arctic Council – the venue for Arctic decision-making” par. 12).

The Arctic Council remains a fundamental organization for promoting international cooperation among states in the circumpolar north. Indeed, the council will continue to determine the region’s economic, social and political development, if it is to handle concerns associated with geographical fluctuations and social activities. As the Council’s organizer, the Arctic region will play a formidable role in giving the region, its distinct identity in the international arena.

Why was the Arctic Council created?

Masters (par. 7) emphasizes that the unknown fascinates people, and adds that new cultures and undiscovered land allures adventurers. Unknown to the world, the Arctic remained remote, away from the interest of scientific explorers and politics. However, the end of World War II saw brought technical advancements that made the region a favorite spot for exploring. The need for resources also turned the world’s eye to the region (“Arctic Council Thrives” par. 14).

Not all the interested parties desired to make the region a playground for advancing the world’s ecology; instead, the Arctic states militarized the region until 1989 when Russia emerged. The Arctic engaged members and observers in meetings that discussed the fragility of the Arctic environment. These meetings also created a potential for cooperating on the numerous approaches of handling this delicate issue (“Arctic Council Thrives” par. 14). The social, economic, political, and physical status of the Circumpolar North remains integral to the creation of the Arctic Council and its continuity.

Political status of the circumpolar north

The political status of the region has attracted attention from several corners of the globe. Countries such as China are gaining interest in the region and have initiated intense lobbying efforts to gain an observer status (“Arctic Council, and the International Arctic Science Committee” par. 21). Although many countries lack direct access to the Arctic region, many clamor for an observer status as an advantage in gaining access to the plans of Arctic players.

Creating good diplomatic ties and relations with the region and the council will increase the profits of involved countries given the easy access to new routes and to natural resources (“Arctic Council, and the International Arctic Science Committee” par. 21). The interests of China in Greenland are evidence of this. The political ties in the region will define the social status of the region given their intrinsic relationship.

Social status of the circumpolar north

As the Arctic undergoes internal and global changes, the necessity for sustainable practices will increase in the social environment (“Arctic Climate Impact Assessment” par. 113). Policies and decisions aimed at promoting sustainable development will act in response to pressures, which are beyond their scope of control. The pressures may include the human health concerns on contaminants in transit to the Arctic.

There are concerns, which arose in the 1990s from the bioaccumulation of organochlorines in food from Europe and Asia. Another instance involved the impact of collapsed markets following anti-fur-and anti-sealskin harvest movements in Western Europe. These two instances, affected the economic and social lives of the indigenous people. Given that the regional change is mostly externally induced, whom sustainable development is directed to beg many answers, since aboriginals are the main residents (“Arctic Climate Impact Assessment” par. 113).

What has attracted most concern is the benefit of sustainability to the aboriginal people. Questions of power, value and knowledge are at the heart of sustainability, because they determine the relative competition for resources. Since the southern metropolitan centers dominate the Arctic region, they view the Arctic as a hinterland that benefits the entire nation. This means the Arctic is shifting into a global and a national necessity that will benefit all the involved nations.

Economic status of the circumpolar north

Out of the desire to profit from increased access to the North, the Arctic states have increased interest in alternative shipping routes. Most notably, Europe has found an economically viable route that will increase its access to the growing consumer market in Asia (“Canada and the Arctic Region” par. 17).

The route will also facilitate getting round the bottle necks present in the Suez Canal. Evidence shows that the Northern Route (NSR) is shorter by nearly twenty percent. In the figure below, the blue line represents the voyage route using the NSR, while the red line shows the route passing through the Suez Canal. The NSR offers the best option for navigating the pirate infested waters of the Suez Canal. Further, the savings in fuel and crew is over forty percent less.

Still, the economic viability of the region remains limited despite the thinning ice. The Arctic is difficult to navigate and has seasonal constraints that may influence its use (Greaves 16). Additionally, the costs of insurance are higher because there are several liabilities that ships crossing the route may face, which insurance firms have not reached a consensus about. Furthermore, given the weak infrastructure in the NSR route, firms are yet to realize the full economic benefits of the trip using the NSR.

The melting Arctic ice is creating economic concerns among the nations that vie for greater influence in the region. Increased shipping, infrastructure, and processing will create economic and strategic competition among involved stakeholders in the region’s operations (Greaves 16). The NSR route will link Europe with Asia, and as a result, will decrease trade using the Northwest Passage. The NSR will connect the Pacific with the Atlantic Ocean, because of possible navigable nature.

Thus, Arctic shipping routes will reduce transport costs to and from Europe and Asia. The Arctic is more advantageous because it cuts some distances travelled by over two-thirds. In addition, most global transportation markets will shift to this trade route during periods of limited ice. The NSR route is an important alternative to evading the piracy issues associated with the Indian and Pacific Oceans (Greaves 16).

Developing the Arctic trade will create an economic power balance for states that use the NSR route. The supply chains will also redefine the balance of power among states that control the routes. As the ice thins, the physical nature of the Arctic will take shape, thereby increasing the region’s viability.

Physical status of the circumpolar north

The arctic landscape has lakes and ponds as their major features. However, some areas have water covering over 90% of the surface, such as the McKenzie or the Yukon Delta (“Canada and the Arctic Region” par. 17). The Arctic constitutes the largest wetland globally with the numerous lakes and ponds that contribute to its biodiversity. Most of the Arctic freshwater ecosystems are a result of the glacial era that created depressions filled with melted water. Additionally, the extreme climate and shallow ponds result in lower hydrological connectivity that freezes the water during cold periods such as winter (“Arctic Climate Impact Assessment” par. 23).

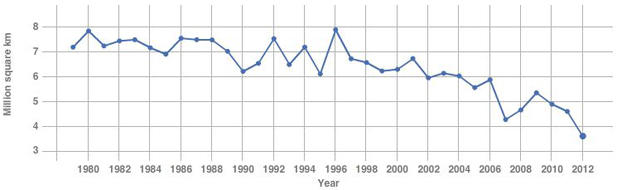

They also influence the structure and dynamics of the ecosystem strongly. Satellite data covering the Arctic region show decreased thickness in Arctic ice. Statistics of the National Snow and Ice Data Centre also show significant decreases in sea ice ranges. Comparing data between 1979 and 2000 with the latest data from 2012 reveals that Arctic ice has shrunk by over 49 percent. This percentage is equivalent to 3.61 million square kilometers of ice.

As the Arctic undergoes swift changes to its physical state, the melting ice is an ecological warning. Literature details evidence showing that the melting Arctic ice has decreased significantly over the past decades (“Arctic Climate Impact Assessment” par. 23). Periods between 2007 and 2012 have witnessed the lowest levels in ice levels over the recent years.

While the ice cap rebound in 2013, analysts predict that the contraction in ice will continue over the coming decades. The level of ice has also remained below the thirty –year average, despite variations in wind and weather patterns. Data from below the surface indicate that the Arctic ice will continue to thin over these coming years because of the melting inclination. Indeed, continuing the greenhouse gases unabated is the only option that may create an ice-free Arctic before the middle of the century.

Industries involved in the council

The industries involved in the council affect the geographical shape of the region. The industries include energy production, shipping, scientific research, fishing, mineral production, and commerce industries (Masters par. 7). The region has faced obstacles in making significant investments in these industries, despite the melting ice.

The shipping industry

The retreating ice cap will open up trade routes to the shipping industry (Masters par 7). The open shipping lanes will complement the conventional routes, thereby enhancing trade further. For instance, the new Northeast Passage gained grip as an optional trade route in 2007. As a result, the shipping industry in the Arctic grew considerably from four in 2010 to 71 in 2013.

The energy industry

Another key industry involved in the council’s operations is the energy industry. Despite varying predictions, the mineral and energy production industry have substantial potential that increases the stakes for countries with interests in the region. A 2008 survey of the Circum-Arctic Resource Appraisal reveals that the continental shelves of the Arctic may form the largest prospect of the remaining Earth’s petroleum deposits (“Statement on Canada’s Arctic Foreign Policy” par. 38). The 2008 survey also shows that thirty percent of natural gas lies within the region, creating potential benefits of the gas industry. Twenty percent of liquefied natural gas also lies within the region. Even without data on conventional resources such as oil shale, the mineral production industry will have potential benefits for the Arctic region.

The commerce industry

Another key player in the Arctic Council is the commerce industry. The commerce industry will grow from the energy related investments based on various factors (“Statement on Canada’s Arctic Foreign Policy” par. 38). These factors include global commodity prices, growing infrastructural developments and technological advancements. Investments from energy and mining industries are significant additions to global investments in the commerce industry. In fact, the current and projected investments in the oil and gas industry will affect economic growth and the world’s energy dynamics.

The mining industry

The mining industry is shaping the interests of the various actors with higher stakes in the region such as Russia (“Statement on Canada’s Arctic Foreign Policy” par. 38). Few countries see the Arctic through the lens of Russia’s eye, as a key investment opportunity. While Russia’s economy depends much on hydrocarbons, most are keen to get a share of the benefits that will arise from the prospect. In the Arctic are over 60 oil and natural gas fields, which Russia dominates.

Although Russia has, 43 fields that state controlled firms direct, there are expectations that they will engage other oil firms in looking for the required expertise to run the sector. The involvement of other companies will be valuable, just as the partnership of ExxonMobil and Rosneft demonstrates. Already ConocoPhillips, Shell and Statoil are foreign companies with drilling leases on the largest projected oil deposits lying in the Arctic region (“Canada and the Arctic Region” par. 33). Additionally, Shell resumed its exploratory drilling in the Chukchi Sea in 2014 after operational problems disrupted its operations two years ago.

Who is a part of the Arctic Council?

The Arctic Council was a product of the Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy (AEPS). The AEPS came to life, with joint efforts from several member countries (“Arctic Council Thrives” par. 34). The AEPS cooperated with the member countries, in investigating the impacts of several developmental activities on the Arctic’s environment. The AEPS engaged in research on pollution and its effects on the region.

Member countries cooperating under the AEPS umbrella considered it untraditional for several reasons (“Arctic Council Thrives” par. 34). First, this avenue facilitated the cooperation of cold war parties towards reaching a single common goal. Next, the AEPS was among the minority intergovernmental institutions that included indigenous aboriginals. After realizing that the Arctic was growing into a global environmental concern, the AEPS gave way to a more able intergovernmental body (“Arctic Council Thrives” par. 34).

Thus, the Arctic Council was birthed as a forum to handle the environmental concerns of the region. The permanent membership of the eight countries in the Council enhanced the cooperation of members towards achieving a common goal. Associating the indigenous people with the council facilitated sustainable development, as the Arctic gained a more stable role in environmental protection.

What is the role of each member?

The Arctic Council outgrew from the AEPS as a Canadian initiative. The member states of the initiative include Canada, the United States, Russia, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Sweden and Norway ((“Arctic Council Thrives” par. 34). Apart from these member states are permanent participants who actively engage in the functions of the Council. These members also consult the indigenous representatives within the Council, a principle that is evident in all of the Council’s meetings and activities. However, the specialized character of many of the Council’s proceedings bars these unique organizations from fully participating in the functions of the Council. All the eight countries play a role in the strategic operations of the Arctic Council.

Norway

In its foreign policies, the Norway government considers developing the North a priority (Perry & Andersen 58). With the focus of developing the region being economical and sustainable, the Norway government has earmarked a significant amount for research activities within the region. Moreover, the Arctic policy of Norway focuses on promoting Russia’s engagement through the NATO, with the cooperation between Russia and Norway remaining an important part of the country’s policy.

Denmark

Denmark plays a key role in the Arctic Council given that its Faroe Islands and Greenland are within the commonwealth of the Realm Denmark (Perry & Andersen 58). Denmark’s role in the Arctic is meant to strengthen and support development in Greenland, in addition to maintaining a United Denmark as a significant player in the Arctic. Denmark is better placed to coordinate long-term sustainable development within the confines of the Arctic Council. Denmark also has significant links with Greenland that could benefit from the Nordic Council of Ministers’ input.

Iceland

Iceland is a member of the Arctic Council with a keen interest in securing its status and influencing international decision-making (Perry & Andersen 58). The Iceland presses for a decision-making capacity within the council, especially on legal, economic and geographical issues. Iceland’s EU membership best places the country in a position that allows it to assert its interests in the cooperative role of various bodies.

Finland and Sweden

The position of Finland and Sweden in the Arctic country is similar, given that neither borders the Arctic Ocean (Charron 28). The policy of the two countries focuses on external relations that take on an international perspective. The two countries push for the development of the Arctic policy in the EU.

Russia

Russia plays a key role in the security policy and economic development of the region (Charron 28). Russia strives to promote peace and cooperation within the region. Indeed, Russia plays a leading role in the Arctic, given its role that extends past its national interests in the region.

The United States

The membership of US in the region is from a modest standpoint that focuses on research and environmental concerns (Perry & Andersen 58). Only until recently has the US given more thought to infrastructure development within the region. The interests of the US lie in sustainable development, security policies, and environmental preservation.

Canada

Canada plays a key role in the Arctic Council, given the impacts of the Council’s operations on its sovereignty (Perry & Andersen 58). Canada has significant interests in the Arctic because of its attachment to the identity of Canada. The influence of Canada in the Arctic stems from promoting sustainable development of its indigenous locals and improving governance of Canadian northerners. Environmental protection is another key interest of Canada that determines its role in the Arctic.

Who are the observer states?

The observer states also form a category of participation. Those who are eligible for observer status include nongovernmental organizations and non-Arctic states (“Arctic Council – the venue for Arctic decision-making” par. 15.). The regional and global intergovernmental bodies are also accorded the status of observers. Non-Arctic states that are permanent observers include the United Kingdom, Spain, and France.

Also included in this list are Germany, Poland and the Netherlands. Both Japan and the European Union (EU) applied for observer status; however, Canada denied the bid by the EU, apparently due to the ban on Canadian seal products. More bodies clamoring for the observer status is an indication of the expanding interest in the affairs of the Council (“Arctic Council – the venue for Arctic decision-making” par. 15.). This will affect Canada’s sovereignty and the potential effects on the environment.

How effective is the council?

The Arctic Council mainly handles collaborative efforts of the region (“Council on Foreign Relations” par. 7). The Arctic Council engages other interregional bodies on issues with increased significance. Together, these joint collaborative efforts help promote a forum for discussing Arctic-related issues. Today, the role of the Council has grown significantly, as the countries add additional observer states in its long list of eight (“Council on Foreign Relations” par. 7).

Canada and Russia, which were initial skeptics, accord more relevance to the expansion of the Arctic Council. In 2012, the Arctic Council convened its business dialogue to discuss responsible industry interaction (“Council on Foreign Relations” par. 7). Through its Sustainable Development Working Group (SDWG), the Council coordinated a multi-sectoral input from various industries involved. With emphasis on the numerous opportunities that the Arctic presents for various involved industries, the meeting concluded that the challenges of operations in the Arctic require extreme focus on sustainable development (“Council on Foreign Relations” par. 7). The Council handles these challenges collaboratively to ensure smooth operations in the region.

The SDWG proposed the development of a structure that could initiate dialogue between the Arctic states and the global business community (“Council on Foreign Relations” par. 7). The business community agreed that defining appropriate standards for collaborative engagement of Arctic stakeholders was an important stepping-stone for improving the region’s performance. The SDWG added that engaging the indigenous locals in addressing rising concerns of their operations and improving their understanding of how they could best develop the available resources sustainably were an important agenda (“Council on Foreign Relations” par. 7).

The council has worked to facilitate the application of environmental efficient technologies. This is aimed at creating a sustainable economic growth for the region. Meetings such as these chaired by the Council are effectively offering innovative solutions for the region’s challenges. Furthermore, the Arctic Council’s position facilitates effective cooperation and dialogue between member states, industries, business and the social community.

What changes have been made since its creation?

Following the 1970 murder of a worker by his boss in the T-3 ice, Iceland in international waters, states could not decide whom the jurisdiction to proceed with the trail fell on (“Arctic Council, and the International Arctic Science Committee” par. 8). Although the station had a US flag, the US held that the Arctic Sea was free from foreign jurisdiction. Therefore, the US remained wary of solutions that would have laid claim to any part of the region. Later, in 2010, a Russian flag flying on the North Pole raised questions about how the rules of politics could be applied to the region (“Arctic Council, and the International Arctic Science Committee” par. 8).

Although the question of whether the Arctic region remains irreconcilably different is unanswered, the Arctic is again attracting key political interest, as climate change makes the region economically strategic. This interest has initiated changes to the operations and the constitution of the Council. Indeed, the quest for natural resources and alternative transport routes has expanded sovereignty claims (“Arctic Council, and the International Arctic Science Committee” par. 8). States, corporations, and nongovernmental organizations, each have visualized for the region. The Arctic contest creates interest in the governance options of the involved states, given its direct relations with the politics of the region. This contest initiated changes to the Arctic Council following its creation.

In May 2013, the US government presented a proposed strategy to the Council (Myers par. 4). Although little information was revealed about the project, the strategy to improve the role of the Council is in the implementation stages. This is evidence that the strategies of the Arctic Council are undergoing definition and will include broader constructs as time goes. The involved countries have an opportunity to consider the resources that they will willingly commit to this region to improve its role further.

Each country will have more defined priorities, as the role of the Council increases significantly. The involved states have to resolve their issues if they are to benefit from the collaborative effort of the region’s plans. Member states will also have to debate issues that will go beyond the scope of the Arctic Council. Indeed, there exists room for improvement in the role of the Arctic Council. Debating on whether the council should move past discussing environmental issues remains a viable option for improvement (Myers par. 4).

With increasing access to the region and the high stakes for all the involved states, analysts propose an increasing role of the Council in addressing militarization efforts. Issues such as natural resource allocation and trade will also gain increasing relevance as the trade routes become more open and as their use increases. Already, Russia has initiated a Northern Sea Route administration, and there are expectations that the Arctic Council will play an increasing role in policy-making in the region. The decision-making role of the Council may also improve significantly, as the council’s role grows past its current limits (Myers par. 4). Currently, the Arctic Council struggles with coordinating decision-making, with the increasing number of member states. The council can explore these changes to improve its role in the region.

Is there room for improvement?

The Arctic Council’s authority remains limited to, environmental concerns, thereby hindering its involvement in various regional issues. The Council omitted issues related to security and peace during its creation, to gain support of the United States (“The Growing Importance of the Arctic Council” par. 6). Despite this omission, the Arctic is today open to new security challenges, as the region opens up its borders for economic exploitation.

Terrorists and immigrants will enter America from the porous North, given its lack of adequate security. Drug smugglers will also see this as an opportunity to further their trade. The Council lacks the ability to mitigate risks such as accidents, which will arise from the increasing traffic at sea and in the air. It is clear that the Council lacks the ability to control the security challenges facing the region. To coordinate cooperation from involved states makes the issues of expansion to cover peace and security a more important concern (“The Growing Importance of the Arctic Council” par. 6). Expanding the Council’s authority to cover the rising transnational security threats is a future direction for improvements that the involved states should consider.

The council could make several improvements, especially in how it handles the disputes involving various nations. There are potential conflicts that may arise, since most states do not accept Arctic boundaries or international law. The borders are potential spots for tensions that may arise if the involved stakeholders do not agree with the other (Barry-Pheby, 23). Already, Norway, Demark, the United States, Canada and Russia, have shown interest in the region, presenting possible conflicts over shifting borders. As countries without coastlines also show interest in the region’s resources, there is a need to discuss the diplomatic and political relations that the council could mend to quell the rows.

The sovereignty disputes in the region require attention that the Council should discuss in detail. The Arctic nations still engage in sovereignty disputes, despite the recent declaration to keep out of the sovereignty of other states. For instance, nations such as the US assert that the Northwest Passage has free navigation rights. On the other hand, Canada claims that the inland waterway is exclusively under its jurisdiction and that no country should lay claim to its sovereignty.

Recently, the Beaufort Sea created border disagreements between Washington and Ottawa, an issue that drew lengthy discussions. Therefore, as the political policies of Arctic states concentrate more on controlling the Northern territory, the Council faces a greater need for oversight in solving the strategically important issues (Barry-Pheby, 23). Given that Russia is economically dependent on energy, the country considers the Arctic a strategic imperative. Still, its ambitious Arctic policies are a response to the security challenges in the Arctic region. Although the disputes are not ending soon, the Arctic Council has to find novel approaches of ridding the region off this menace.

Canada and the Arctic Council

The Northern Arctic covers over two fifths of Canada and houses more than 111,700 Canadians (Barry-Pheby 261). The north also covers over two thirds of Canada’s coastline, an area of roughly 3.5 million square kilometers. Canada’s foreign policy in the Arctic advances its interests in the domestic and international front. Therefore, creating a northern strategy for the Arctic has enabled the government to unlock its true potential.

Canada is keen on exercising its sovereignty and the Arctic Council offers the best forum for advancing its international welfares. Canada was the first chair of the council between 1996 and 1998 (Andrea 774). As chair, Canada continuously supports much focus on the human dimension of northern inhabitants. The country recognizes the role that the Arctic Council plays in shaping its international actions. Canada also respects the input of indigenous organizations in the North, especially permanent participants, in its actions. As chair, Canada continues to involve permanent participants in ensuring the efficient development of the region.

The country remains committed to working with Arctic states by taking an active leadership role in the Council’s operations. Canada proudly chairs the Arctic Council since it took the mantle in 2013. Before it resumed chairpersonship, Canada rallied behind the key theme of developing northerners (Barry-Pheby 261). Canada championed development for the northerners by laying more focus on resource development. Canada also focused on safe shipping and sustainable practices among the region’s communities. Canada knew well that satisfying the interests of the indigenous people before any other concern was a priority.

How they prepared for the chairpersonship

Barry-Pheby (261) states that Canada faced several opportunities and challenges in preparing for its chairpersonship. Canada’s position as chair better positioned it to advance its foreign policy in the Arctic. The opportunity was important to Canada given their interest in the economic growth of the region. Faced with the opportunity to engage northerners in prioritizing on climate change and issues related to its interests in the north, this was a significant time for Canada. With this in view, displaying the potential of the north of the national and international arena took center stage (Barry-Pheby 261).

As chair, Canada called meetings to address issues, which they felt related to the long-standing challenges facing the Arctic. Canada also discussed emerging issues that were critical of the Council to address cooperatively during their tenure as chair. The government of Canada announced its overarching theme that framed its period as chairperson from the period of 2013 to 2015. Canada looked at the issues from a broader perspective by engaging its parliament.

Issues that concerned Canada most were environmental concerns, geographical access, and legal-political environment. As chair, Canada encouraged firms to increasingly head north to the unexplored arctic basins, while striving for better opportunities and advanced technologies with more benefits to the commerce industry (“The Growing Importance of the Arctic Council” par. 7).

Their duties in the council

Canada, as chairperson of the council, negotiates legal binding instruments such as the Agreement on the Cooperation in Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue in the Arctic (“Statement on Canada’s Arctic Foreign Policy” par.13). Under the Nuuk Declaration, Canada has initiated projects such as the Emergency Prevention, Preparedness and Response Working Group. As chair, Canada has led significant scientific assessments in various aspects of environmental protection within the region. Later Canada carried out the Snow, Water, Ice and Permafrost in the Arctic Assessment (“Statement on Canada’s Arctic Foreign Policy” par.13).

Canada’s foreign policy for the Arctic leads the pack in monitoring the living resources of the indigenous communities in the Arctic. Canada assesses, monitors, and encourages considerate thought about the Arctic’s human dimension, with the intention of its inhabitants at heart. As chair, Canada led various environmental protection projects and initiatives that influenced its understanding of the region. These include the Arctic Ocean Review Project and the Arctic Maritime Shipping Assessment.

What they are continuously doing to ensure all policies are enforced and are they fulfilling their duty as the chairperson?

The Arctic Council uniquely includes six indigenous peoples’ organizations that are recognized internationally (World Economic Forum 6). Of the six, three cross-border organizations were formed with the interest of Canadians at heart and focus on improving their lives significantly. The Canadian government includes permanent participants in its Arctic foreign policy. Having these common agendas facilitates strong and responsible governance for the Arctic region (World Economic Forum 6).

The Canadian government includes its indigenous inhabitants in shaping its foreign policies. The indigenous permanent participant organizations also facilitate proper regional policies and governance. According to World Economic Forum (6), the Canadian government supports the permanent participants financially to strengthen their full participation in the council’s affairs. The Canadian government also supports the full participation and consultation of the permanent participants because of their representative capacity for the indigenous inhabitants.

As non-members of the Arctic Council grow, Canada is better placed to ensure that its permanent participants maintain their role in the Council. The government of Canada consults and works closely taking into consideration the perspectives and views of every involved party (World Economic Forum 6). Canada also tries to achieve its objectives within a timeframe of realistic agendas and mandates, making sure that they enforce their policies.

To make sure that its policies are enforced, the Council has fostered cooperation through its environmental concerns for the Arctic region (“Statement on Canada’s Arctic Foreign Policy” par.13). With the environmental strategy forming the major work of the Council after its founding in 1996, the Council conducted a comprehensive assessment of the Arctic’s climate. Climate change attracted attention of the Council because of its implications that are broader than the region. As changes in the circumpolar north progress, climate change will remain a key concern of the Canadian government and the Arctic Council.

Canada is more concerned with climate change and the country’s adaptation strategies. Therefore, the Arctic Council’s policies related to climate change will have considerable impact on Canada. The Council has to reinforce its focus to the adaptation measures for its circumpolar residents. With a majority of the council’s work related to environmental protection, it will need to focus more on monitoring environmental threats within the Arctic and on arctic conservation ((“Statement on Canada’s Arctic Foreign Policy” par.13).

The fragility of the north requires the Arctic Council to engage in planning sustainable development activities that protect the environment. Presently, marine protected areas do not exist and the Arctic Council is far from instituting an ecosystem approach to govern the shipping and pollution in the North. Experts say that the best bet is addressing climate change by considering the delivery and outcomes. Canada is better placed to follow up on the regional climate impact assessment that was completed in 2004. Canada, through its chairpersonship, can focus on this aspect in addressing related policy issues

The stand of the Council on the Canadian Arctic will influence the policies associated with Canada’s sovereignty in the region (Council on Foreign Relations” par. 11). Canada’s sovereignty is a significant issue in the north, especially its human dimension. Many experts assert that Canada’s sovereignty over the Arctic is established and that no one is disputing its legal position. Therefore, no state will challenge its Arctic territory.

Experts agree that the issue on Canadian waters is complicated since no one is disputing Canadian waters, but the extent to which it can control foreign navigation. Canada lacks an international strait on the waters, and can manage the situation better by treating and managing it as internal waters that are subject to international navigation. Therefore, how the Canadian government enforces its legal position through policies will gain significance as maritime traffic increases.

Although the sovereignty of Canada over the Arctic is not threatened, its ability to enforce rules and compliance with Canadian laws for maritime traffic will be a major concern. The Arctic Council has to ensure that Arctic states invest in maritime infrastructure and work out a solution to the compliance with regulations in Canadian waters.

Canadian Priorities in the Arctic Council

The council was created to encourage cooperation among countries with territories above the Arctic Circle (Council on Foreign Relations” par. 11). Canada found the Arctic Council in 1996 as an intergovernmental forum that promoted discussion on issues concerning the environment and research. The Council lacks the decision-making power required to further its interests in the region. During this period, the US opposed the underfunded Arctic Council that was only noticeable until recently. In 1996, the Arctic Council was established without terms and rules of procedure (Council on Foreign Relations” par. 12).

Although previously without a secretariat, the council today enjoys a principal forum that facilitates the interaction of eight member states. This interaction also facilitates the planning of the Arctic’s future. “Arctic Council, and the International Arctic Science Committee” (par. 34), points out that various factors led to the creation of the Arctic Council. First, the northern aboriginals cooperated to assert their autonomy in the region. Second was the increasing environmental concern, especially with global climatic change. Exposure of the Arctic inhabitants to organic pollutants was also a key issue of concern.

Last, the Cold War ended, leaving a more militarized Arctic. While the Canadian government emphasized its sovereignty by allowing resettlements in the region, they could no longer engage in such actions by 1970s (“Arctic Council, and the International Arctic Science Committee” par. 34). The Inuit families that were resettled in the high arctic demanded a stake in deciding any actions related to their future by engaging in a rights revolution.

What are Canadian interests?

Canada has many interests in the region that could have an impact on its activities within the region (“Statement on Canada’s Arctic Foreign Policy” par 15). The Canadian Arctic faces challenges, which the Council can pursue significantly. The challenges, which have been mentioned at hearings, include the ship and safety standards in the Arctic. Another challenge is the oil spill preparedness and response tool that could help safeguard its interests in the maritime industry. Implementing a search and rescue instrument is also in the list of Canada’s priorities.

Following discussions, the Canadian government agreed that developing the northern regions was a weighty issue that required urgent redress. This increased the possibility of creating a fisheries management for the Arctic Ocean. Weighty issues for Canada include responsible Arctic resource development. Emphasizing knowledge sharing and identifying significant best practices is the first step towards responsible resource development. These interests are important to Canada if it is to gain significantly from the benefits of traffic increase within the region.

The melting Arctic ice is opening up the region to resource exploitation that was not possible over the past decades (“Canada and the Arctic Region” par 7). A 2008 Geological survey by the United States shows that the region is home to over 30% of global natural gas resources. Further, 13 percent of global undiscovered oil lies within the region. The survey documents that as the ice thins and retreats, it is facilitating the creation of new trade routes. For instance, 46 ships carrying over 1.3 million tonnes passed through the Northern sea route in 2013, representing an increase of over 480, 000 tonnes from the previous year (“Canada and the Arctic Region” par 7).

The increasing significance of the NSR route motivated the supervisory role of Russia in the region’s shipping industry. The move by Russia motivated Canada to reconsider its role in the Arctic region, if it were to defend its interests from foreign influence.

Emphasizing the relationship between domestic and foreign policy is linked to creating sustainable circumpolar communities. Cooperating to address these issues alongside safe Arctic shipping will aid the Council in findings common approaches to the issues (“Canada and the Arctic Region” par 7). For instance, Canada just as the rest of the rest of states alongside the Arctic considers sustainable communities a major concern. The council’s nature of determining priorities through consensus will require collective determination with Arctic state partners.

How does the council affect the Canadian Arctic? (Pros/cons)

The Arctic Council has a huge impact on Canada’s vision for stability in the region (“Canada and the Arctic Region” par 7). Canada desires a rule-based Arctic that has well-defined boundaries to facilitate good governance for the region. Canada’s intent is on fostering economic and social development for the region, thereby creating dynamic economic growth and demonstrating responsible stewardship for the region. To create a region with its best interest and values at heart, the Canadian government is moving towards creating a more vibrant community for the northerners (“Canada and the Arctic Region” par 7). However, the Arctic Council has influence that could sway this growth both positively and negatively.

The Council’s stand on the opportunities and challenges that the region faces will have significant impacts on the Canadian Arctic. The region has greater implications for Canada given its criticality as an economic hub. Despite the opportunities associated with the Canadian Arctic as an economic hub, there are several social, economic and environmental issues to address from domestic and international dimensions. The Arctic will play a key role in addressing these issues, because of its strategic placement in the region.

Dispute resolution

Legal disputes such as the land dispute between Canada and Denmark concerning the Hans Island, the maritime boundary dispute between Canada and Denmark over areas of Greenland and Ellesmere Island, and the dispute over the Beaufort Sea with the United States do not constitute a sovereignty crisis (Dadwal 812). Canada insists that the disputes are resolvable according to international law, with the government insisting that it will pursue its legal positions diplomatically.

The Arctic Council will play a more refined role in managing the disagreements while increasing Canada’s collaborative position with other Arctic nations. The Arctic Council will also play an important role in ensuring that friction does not occur between the involved states. Since none of the disputes is a crisis, the Arctic Council can foster cooperation, thereby addressing the opportunities and challenges arising in the Arctic North (Dadwal 812).

Black Carbon

Black carbon is creating concerns for the environment and health. While ice and snow reflects 90% of the sun, the opposite is true if soot falls on snow (Stulberg 5). Black carbon raises concerns because of its accelerating ability on climate change, resulting from climate change. Additionally, most of the snow melting in the Arctic is a result of the particulate. Experts argue that enhanced cooperation between members of the Arctic Council is required if the region is to cooperatively slow down the effects of climate change in the region.

The Arctic Council can work with the Canadian government to institute strong measures that can negotiate black carbon in the circumpolar region. Canada should expect resistance in cooperation to control black carbon, especially after the failed US and Canada cooperation in minimizing acid rain in the region during the nineteen eighties and nineties. Canada and the US disagreed on the remedial actions to take, an example that makes vital for the Arctic Council to take the lead in addressing this issue.

Scientific research and cooperation

Scientific research intrinsically links to addressing climate change and environmental protection (Perry & Andersen 23). The changing nature of the Arctic makes exercising the best science to deal with these issues an important step. Canada requires a science policy for the active north, which could double up as a foreign policy for the Canadian Arctic. A research station will be valuable to Canada, since it will enhance scientific information on sustainable development within the region. A research station will also enhance Canada’s knowledge of the Arctic, thereby improving the lives of northerners (Perry & Andersen 23). The Arctic Council is better placed to enhance bilateral scientific cooperation now with Canada as chair and after 2015 when Canada will take the chairpersonship.

Maritime traffic

Climate change is reducing sea ice cover, thereby opening up the Canadian north to developing its natural resources. With the long Arctic coastline, Canada should be prepared to manage the increasing maritime traffic in its waters given the impacts of increased vessel activity (“The Growing Importance of the Arctic Council” par. 7). Canada has to remain attentive to ship standards and regulations to enforce the legal regime in the arctic waters. Canada should prioritize on safe and responsible shipping alongside its search and rescue capabilities. Additionally, implementing a search and rescue capability requires significant Canadian resources, especially after the Arctic Council reached this binding agreement.

New shipping routes

It is documented that the Arctic routes will be shorter as compared to alternative routes, as resource development projects proliferate the North (Griffiths 257). Maritime traffic, engaging in commerce will increase considerably, as the area opens up to international commercial activity. Despite this, experts have not given a sober analysis of the present and predicted trends. According to Griffiths (257), the Arctic waters are hazardous to ships given that the changing ice patterns do not to signify the absence of ice since the composition of ice may be predictable.

While the Northwest Passage promises quick transition to the west, the area remains treacherous and dangerous with the breaking ice that is floating south. The shipping in Canadian Arctic waters will increase because of mining projects that connect to resource development and exploration (Griffiths 257). Canada will become busier and crowed as maritime activity increases. Therefore, it is important that Canada monitors and controls its traffic to protect the environment. Canada and its partners need to institute regulatory frameworks and infrastructure that will manage increasing airtime traffic.

Conclusions

Following the cold war, the Arctic region underwent unprecedented change. Accordingly, the Arctic and the international community faced several global environmental concerns. The increasing interest of several parties in the affairs of the region, especially in relation to natural resource exploitation presented the Arctic Council with more challenges. Countries that were laying territorial claims to the region had differing interests that created new political concerns for the Council.

Today, concerns relating to maritime transportation as well as infrastructure are resurfacing as the economic potential of the Arctic becomes more glaring. The rich natural resources are stimulating the international community’s interest in the region. Of much concern is that since 1996 and the present, the Arctic region has not set a common political agenda that will facilitate smooth cooperation between the northern countries. A legal framework for the economic activities in the region is also lacking, with the inclusion of the indigenous people growing into a sidelined concern for countries laying territorial claims to the region.

The coastline of the Arctic region also lacks the necessary infrastructure that can handle the increasing economic activities in the region. Therefore, the Arctic region has to undertake these measures jointly, if they are to have the desired effect. Including the Arctic states in the Council’s policymaking is the best bet for addressing these concerns. The Arctic Council lacks the necessary mandate that may prevent the isolated decision-making among countries involved in the Arctic region.

This limited decision-making ability has created an incomplete framework for the region. The Arctic states understand this situation and many advocates for a more involved role of the Council to handle the rising contemporary challenges. The regional states recognize the role that a stronger Arctic Council could play in the region. Therefore, the Council proposes that over the next years, the Arctic Council should receive a higher role that could rival the region’s international actors. States merged to reform the Council to keep it in tandem with the present-day challenges. States also have to broaden their mandate to issues that transcend the environmental concerns if the Arctic Council is to get the high-level image.

With regional cooperation being a key constituent of Canada’s foreign policy, Canada can build on its achievements and strive towards improving several policy areas. With Canada as the chairperson of the Arctic Council, the country should engage in several priority areas that requires redress in its own north. This will aid in laying groundwork for the northern communities, thereby strengthening its ability to push forward its Arctic foreign policy.

From this review, it seems that Canada should work towards approaching its domestic and foreign policies for the Arctic region by considering the pros and cons of its actions. This case is true for infrastructural investments, which the northern community needs to take advantage of the economic development opportunities in the region. The investments will also ensure that the Canada engages in monitoring and enforcing its authority over maritime traffic, while engaging in rescue operations within its waters.

Canada also needs to act further on black carbon, which advance growth, but harm human health and the environment. Integrating these issues in policy making will enhance Canada’s role in the region, thereby giving the country new strategic dynamics.

Canada’s foreign policy on the Arctic has considerable impact in the broader multilateral arena. The details of this research contribute to the Canadian strategy for the Arctic and could help inform policymakers on priories and actions that are needed beyond the chairpersonship of Canada. Overall, this study leaves the impression that the Arctic is an avenue for potential economic growth that can only flow from sustainable economic development. Innovation and community resiliency are factors that may aid this flow of economic growth.

Clearly, the Arctic region will undergo dramatic changes that will redefine the future of the region. The global environment and economic forces will interact, thereby opening up the Arctic to numerous prospects that tag along risks; and, Arctic governments must learn to manage these risks. Canada’s role as chairperson of the Arctic Council better positions it to manage these risks. With the stated conclusions in mind, it is important for the Arctic Council to work towards implementing the recommendations within this paper, if it is to develop into an international region with a distinct identity.

Works Cited

Andrea Charon. “Canada and the Arctic Council,” International JournaI 67.2 (2012): 774. Print.

Arctic Climate Impact Assessment. Arctic Climate Impact Assessment, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005. Print.

Arctic Council – the venue for Arctic decision making. 2014. Web.

Arctic Council Thrives. 2014. Web.

Arctic Council, and the International Arctic Science Committee. Impact of a Warming Arctic: Arctic Climate Impact Assessment, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004. Print.

Barry-Pheby, Emma 2012, Examining the Priorities of the Canadian Chairmanship of the Arctic Council: Current Obstacles in International Law, Policy, and Governance. Web.

Canada and the Arctic Council: An Agenda for Regional Leadership. 2013. Web.

Canada and the Arctic Region. 2011. Web.

Charron, Andrea 2014, Has the Arctic Council Become Too Big? Web.

Council on Foreign Relations 2014, The emerging Arctic. Web.

Dadwal, Shebonti. “Arctic: The Next Great Game in Energy Geopolitics?” Strategic Analysis 38:6(2014), 812-824. Print.

Greaves, Wilfrid 2014, Arctic Council: Canada, Circumpolar Security, & The Arctic Council. Web.

Griffiths, Franklyn. “The Shipping News: Canada’s Arctic Sovereignty Not on Thinning Ice.” International Journal 58.2(2003): 257-282. Print.

Masters, Jonathan 2013, The Thawing Arctic: Risks and Opportunities. Web.

Myers, Steven. “Arctic Council Adds 6 Nations as Observer States, Including China.” The New York Times. 2013: 2. Print.

Perry, Charles and Andersen Bobby. 2012, New Strategic Dynamics in the Arctic Region: Implications for National Security and International Collaboration. Web.

Statement on Canada’s Arctic Foreign Policy. (2010). Exercising Sovereignty and Promoting Canada’s Northern Strategy Abroad. Web.

Stulberg, Adam. “Russia and the Geopolitics of Natural Gas: Leveraging or Succumbing To Revolution?” PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo 296(2013): 1-6. Print.

The Growing Importance of the Arctic Council 2013. Web.

World Economic Forum 2014, Demystifying the Arctic’, World Economic Forum Global Agenda Council on the Arctic. Web.