Introduction

Plato was the first to define causation, stating that everything that comes into being or changes must be due to some cause, as nothing can exist without one. In epidemiology and public health, the term “cause” is used to describe the cause of a disease. The ability of one variable to influence another is known as causation. The first variable may cause the incidence of the second variable to fluctuate, or it may cause the incidence of the second variable to change. It can be seen as a genetic link between phenomena in which one thing (the cause) gives rise to something else (the consequence) under particular conditions. In epidemiology studies, causation identifies the etiology of a disease and thus characterizes other health outcomes. Causation aids in disease diagnoses, such as disease observation and technical laboratory diagnosis. Because epidemiology deals with the frequency, distribution, and determinants of disease, all parts of epidemiology can be examined and discovered through epidemiological study design, leading to the etiology of a disease.

Illness Etiology

Given that causation refers to illness etiology, a disease’s cause can be divided into two categories: primary and secondary causes. The principal cause of an illness, also known as the etiologic agent of a disease, is critical since its absence suggests that the condition is less likely to occur. Because it is more widely known, an etiologic agent is employed instead of the principal cause of a disease (Shah and Khan, 2019). Bacteria, viruses, and parasites are the most common etiologic agents that cause infections. In the case of tuberculosis, the etiologic agent is Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which is critical in the disease’s development and must be identified before treatment.

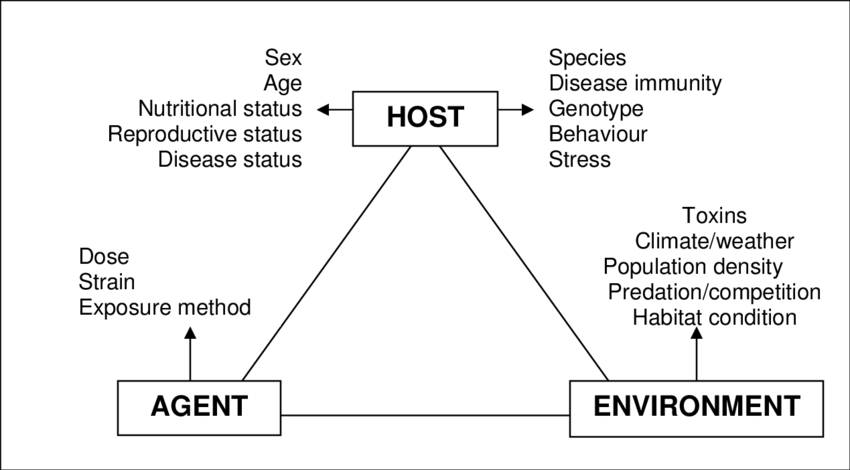

Secondary causes, also known as risk factors, are factors that contribute to, predispose to, and exacerbate disease in a population. Secondary sources, on the other hand, are not required for the occurrence of a disease but are necessary for diagnosis and treatment (Adhikari et al., 2020). For example, the etiologic agent of malaria is the anopheles mosquito. Because the environment promotes mosquito breeding, combating malaria will necessitate a greater focus on the environment and other environmental elements that aid mosquito breeding in the area, as well as methods to eradicate them. With the concept of environment comes the relationship between a host, an agent, and the environment, all of which must be taken into account. The environment in which a host is found can have an impact on the agent, putting the host at risk of infection. Agents require a healthy environment in which to live and grow, and this environment must be monitored to ensure that people remain healthy following intervention. The interaction between the host, agent, and environment is depicted in Figure 1 (Fraser and Parmley, 2019).

When dealing with illness causation in epidemiology, it is important to grasp the relationships between host-environment, host-agent, and agent-environment, as shown in the figure above. Any living animal or plant on or in which a parasite can live, including humans, is referred to as a host. These parasites can be damaging to the host and cause diseases in the environment. An agent is a factor that prevents the occurrence of a disease when it is absent. Viruses, bacteria, and parasites can all be agents in infectious disorders (Johnson-Walker and Kaneene, 2018). Cholera cannot live without the presence of vibrio cholera (Harb et al., 2019). Finally, the external component that influences health is the environment. It is further broken down into three categories: social, biological, and physical. Culture, jobs, politics, and other facets of people’s social life can all be part of their social contexts. Plants, vectors, and humans can all function as reservoirs for infectious illnesses in biological ecosystems. The physical environment includes factors such as proximity to toxic sites, climatic conditions, and pollution.

Risk factors are conditions, qualities, or characteristics that raise an individual’s chances of developing, or being adversely affected by, a disease process. The risk factor does not have to cause the disease, but it does raise the chances that the person who is exposed to it will develop it quickly. Hill’s criteria for causality are a set of measurements suggested by Sir Austin Bradford Hill that are widely employed. It was an elaboration of a set of criteria standards previously presented in the seminal Surgeon General’s Report on Smoking and Health (Cox, 2018). Hill’s criteria for causality includes association strength, consistency, temporal relation, specificity, biological gradient and rationale, coherence, and evidence (experimental and analogous).

Epidemiological Study Designs

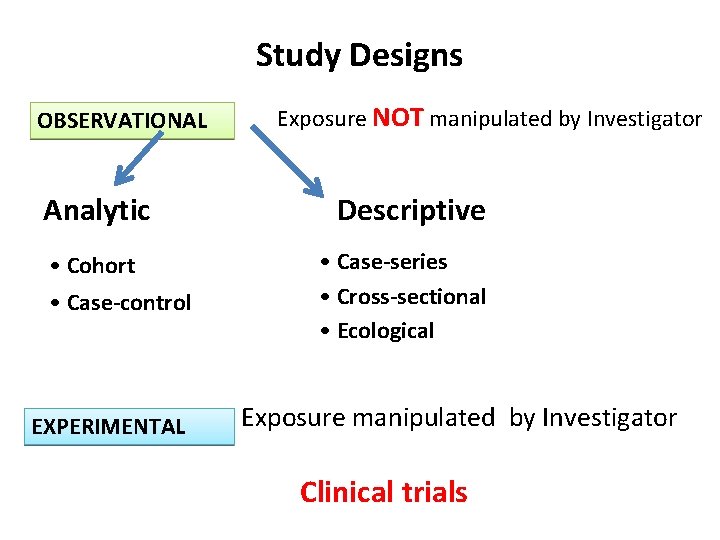

There are common epidemiological study designs used in determining casualty, including observational studies, ecological studies, and community randomized trials.

Observational studies

An observational study in epidemiological studies involves observing what occurs within a study population. With no intentional manipulation of exposure settings, the investigator observes and records data on the group of people, generating information on the links between exposure and disease as they naturally unfold (Awortwe et al., 2019). Descriptive research meant to explain the distribution of one or more variables without making any causal conclusions is an example of an observational study. These studies cannot pinpoint the cause or level of exposure, but they are great for creating hypotheses for future research. Observations can be analytic or descriptive and include case-control, cross-sectional and ecological studies as seen in Figure 2.

Descriptive case control studies are case reports that describe a patient who has a unique disease or is suffering from multiple conditions at the same time. Descriptive studies can be of several types, namely, case reports, case series and cross-sectional studies. Although many case reports are of minimal significance, some of them bring previously unknown diseases to light and play a vital role in medical research. For instance, HIV/AIDS was first recognized through a case report of disseminated Kaposi’s sarcoma in a young homosexual man and a case series of such men with Pneumocystis cariniipneumonia (Aggarwal and Ranganathan, 2019).

A descriptive cross-sectional study is one in which data is collected on the existence or amount of one or more variables of interest (health-related characteristics), whether exposure (e.g., a risk factor) or outcome (e.g., a disease), as they exist in a defined population at a specific period. Cross-sectional studies provide a “snapshot” of the frequency and features of a disease in a community at a specific point in time. These are excellent for determining the prevalence of an illness or a risk factor in a group of people.

Ecological or Co-relational Studies

Ecological or co-relational studies look at populations or groups of people rather than individuals as the units of research. Ecological studies are notoriously difficult to comprehend. Typically, data sets collected for other objectives are used in this study. As a result, data on various exposures and socioeconomic factors may be unavailable.

Analytical Research

Analytical studies take a step further by looking at the connections between health and other variables. Cross-sectional studies and cohort studies are two main types of investigations in this study research. Such studies are observational in nature and provide a snapshot of the features of the research subjects at a specific point in time. In contrast to cohort studies, cross-sectional studies do not require a follow-up period and are thus more straightforward to conduct. This particular study design, which is the weakest of the observational designs, cannot prove a cause-effect relationship since the exposure status and outcome of interest information are collected at a single point in time, usually through surveys. This research method is commonly used to determine the prevalence of a disease in a population.

Patients are originally divided into two groups based on their exposure status in cohort studies. Cohorts are followed throughout time to see who develops the disease in the exposed and non-exposed groups. It is feasible to conduct retrospective or prospective cohort studies. Unlike case-control studies, which begin with diseased and non-diseased individuals, cohort studies begin with exposed and unexposed patients, allowing for direct incidence computation. The effect of a cohort study is quantified using relative risk. The downside of cohort studies is that they are more prone to selection bias. When examining rare diseases and outcomes with long follow-up periods, cohort studies can be very costly and time-consuming.

Conclusion

Both the etiologic agent and risk factors have a role in disease etiology. This idea is crucial for epidemiologists to understand since it allows for proper intervention during outbreaks and other health situations. Epidemiological study designs are put together to identify the source of disease, which means that they play a significant role in determining the cause of disease. In health sciences, epidemiology is important because it describes all elements that influence disease, including the environment. Let us make an effort to collect data to avoid errors while assisting our folks.

Reference List

Adhikari, S.P., Meng, S., Wu, Y.J., Mao, Y.P., Ye, R.X., Wang, Q.Z., Sun, C., Sylvia, S., Rozelle, S., Raat, H. and Zhou, H., 2020. Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak period: a scoping review. Infectious diseases of poverty, 9(1), pp.1-12.

Aggarwal, R. and Ranganathan, P., 2019. Study designs: part 2–descriptive studies. Perspectives in clinical research, 10(1), p.34.

Awortwe, C., Makiwane, M., Reuter, H., Muller, C., Louw, J. and Rosenkranz, B., 2018. Critical evaluation of causality assessment of herb–drug interactions in patients. British journal of clinical pharmacology, 84(4), pp.679-693.

Cox Jr, L.A., 2018. Modernizing the Bradford Hill criteria for assessing causal relationships in observational data. Critical reviews in toxicology, 48(8), pp.682-712.

‘Experimental Study Design’ [PowerPoint Presentation]. RCT. Web.

Fraser, E. and Parmley, E. J., 2009. Health assessment and management resource for species at risk in British Columbia. In Environmental science (pp. 11).

Harb, A., Abraham, S., Rusdi, B., Laird, T., O’Dea, M. and Habib, I., 2019. Molecular detection and epidemiological features of selected bacterial, viral, and parasitic enteropathogens in stool specimens from children with acute diarrhea in Thi-Qar Governorate, Iraq. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(9), p.1573.

Johnson-Walker, Y.J. and Kaneene, J.B., 2018. Epidemiology: Science as a tool to inform one health policy. Beyond one health: From recognition to results. Hoboken: Wiley, pp.3-30.

Shah, S.S.A. and Khan, A., 2019. One health and parasites. In Global Applications of One Health Practice and Care (pp. 82-112). IGI Global.