Introduction

The depiction of the same phenomenon, figure, or process undoubtedly leads to different interpretations. This is quite natural since the personal perception of the observed object cannot be the same for people with different cultural, ethnic, and worldview views. One fundamental example of variation is the fact that there are four different gospels as forms of description of the life and life of Jesus Christ.

The four canonical Christologies of Matthew, Luke, Mark, and John are different versions of the same story of how Jesus lived and performed miracles. However, it should be clearly understood that the Gospels, while fundamental and sacred, are not exhaustive teachings on the life of Christ, for they leave out many details of Jesus’ domestic activities. For example, readers and listeners of the New Testament are well aware of how Jesus walked on water and healed a leper but are not familiar with such details of his life as a detailed description of his appearance and his marital status (Matt. 14:22-33; Matt. 8:1-4).

A consistent and systematic study of the books of the New Testament allows us to summarize the data and compile the complete portrait from fragments of information. However, it is a theological fact that each of the gospels has its own view of Christology, which means that the story of Jesus has been “passed through” the filter of perception of the author who authored the sacred book. At the same time, it is clear that each of the four authors viewed the Son of God through the paradigm of the dominant image: Jesus could be presented as Savior, Servant, or Miracle Worker.

For the purposes of this study, the Gospel of Matthew was assigned as the central book of the New Testament, the first among the four sacred books. It is known for a fact that this gospel was written to fit the context of the Jewish communities, and therefore this book is characterized by an excess of references to Old Testament texts, probably as a way to motivate the Jewish population to read the Gospel of Matthew.

As one carefully reads this book of the New Testament, it becomes clear that Matthew sees Jesus as the Messiah (the teacher) who came to save the people. The second part of this study will show that academic and theological literature agrees with this interpretation. Thus, the overall purpose of this paper is to examine the image of Jesus Christ as Messiah through the lens of Matthew’s perception as the author of one of the canonical gospels.

Summary of the Features of the Gospel of Matthew

In discussing the central prism used by the author during his description of Christology, it is impossible to ignore the fact that the gospels differ from one another. Only a comparative analysis with a focus on the Gospel of Matthew becomes a crucial tool to qualitatively answer the question of why Matthew portrays Jesus in a particular light.

Therefore, it is essential to emphasize key unique aspects of this gospel that allow for a deeper understanding of the essence of Christology. The immediate recognition is that Matthew wrote his portion of the New Testament for a Jewish audience in the Jerusalem community. From this comes a second feature, which is the multiplicity of citations of Old Testament texts in his Gospel. An independent count shows that Matthew’s Gospel includes over 120 direct and indirect references, including allusions and paraphrases.

Such a large, but most importantly, unified quotation of the Old Testament with an emphasis on texts dealing with the Messiah is not accidental, but on the contrary, was entirely deliberate on Matthew’s part. Furthermore, unlike the other canonical books of the New Testament, Matthew’s Gospel has no explanation for traditional Jewish rulings and norms since there is no need for the Jerusalem reader to clarify familiar concepts.

It is important to note that the term “God” does not appear — or appears very rarely, depending on the translation — in Matthew’s Gospel. Once again, this phenomenon is not coincidental since it is known that the use of this word did not characterize the Old Testament Jews, unlike Christians, for whom, for example, Luke wrote. This does not mean, however, that Matthew completely excludes God’s message from his gospel: keeping the essence of Christology virtually intact, the apostle could not distort the sacred teachings.

For this reason, Matthew replaces the term God with tetragrams or synonyms so as not to emphasize God to his readers, although it is evident to the modern reader what the evangelist has in mind. It is also impossible not to notice the particular use of numbers in this Gospel: Matthew deliberately uses the number “14” to refer to Jesus’ lineage. There are no precise definitions of the meaning the apostle put into this number. It could either be a double “7” as evidence of Jesus’ sacredness or it could be a reference to the Lunar Month lasting precisely 28 days.

Finally, a final aspect important for preliminary discussion in the current research paper is a clear focus on the figure of the apostle Peter, which is not seen in the other gospels. The apostle Peter, aka the first pope, was one of Jesus’ closest disciples during his lifetime, and it was he who, according to Matthew, experienced one of Christ’s most famous miracles. Specifically, Jesus helped Peter, who was drowning, get up on the water and go during the storm at sea. Considering all of the above, it is critical to emphasize that Matthew, who wrote his version of the New Testament for the Jews, accurately recorded the figure of Jesus as a savior and teacher for the whole world.

The Author’s Perception of Matthew’s Gospel

According to the instructions, the primary assignment was to read the assigned book independently and find the dominant image of Jesus described by Matthew without the use of academic literature. In this sense, a careful reading of the Gospels was an essential step in establishing a primary, subjective view of how the apostle was able to portray Jesus. Although there are images of Christ as a teacher, helper, and one of Abraham’s descendants in Matthew’s sacred work, this is especially important for a Jewish audience of readers and hearers. However, according to the author, the primary and predominant portrayal of Jesus was that of the Messiah. Messiah has no unambiguous interpretation for the theological and scholarly communities, and many authors tend to interpret the term differently. In addition, there is no single field of knowledge within which the phenomenon of the Messiah is studied.

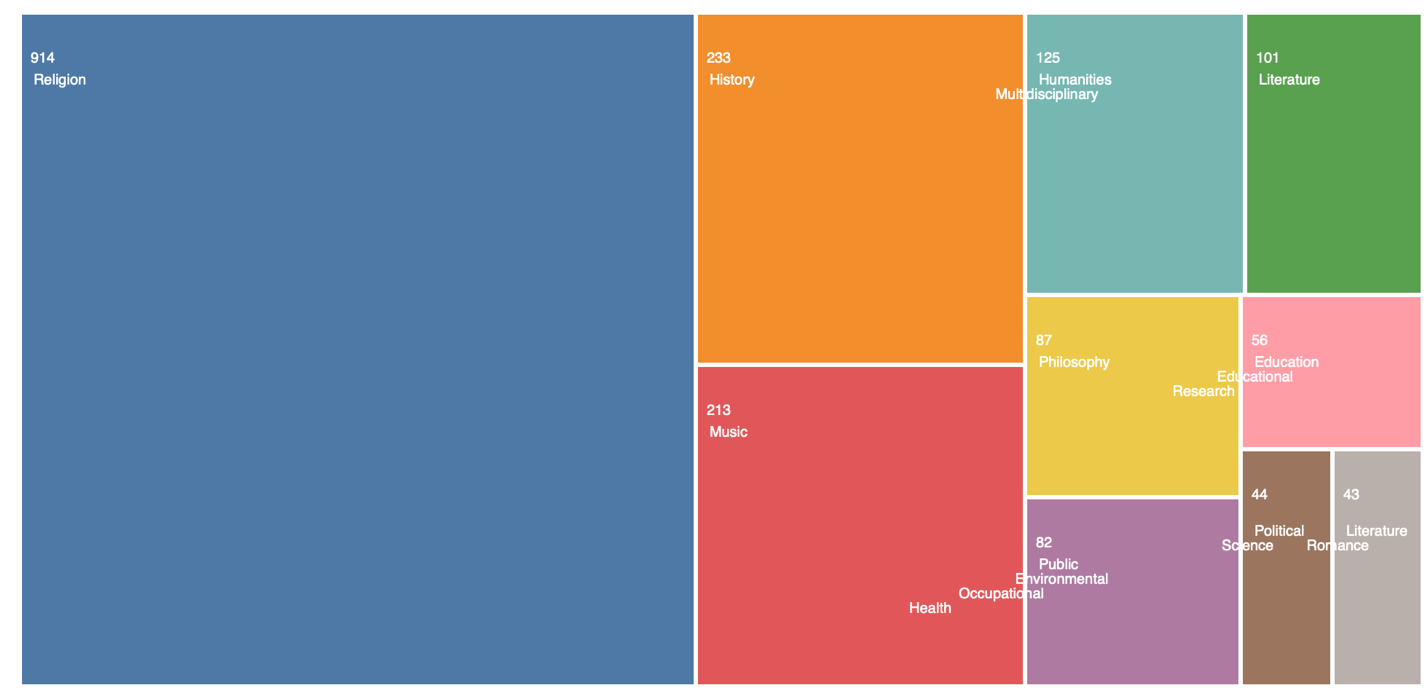

More specifically, Figure 1 shows the ten academic categories in which papers with the key term “Messiah” have been published. It can clearly be seen that this includes not only religious sources but also historical, musical, multidisciplinary, literary, philosophical, political, and educational writings by authors. To put it another way, it is impossible to provide a uniform conceptual framework for the term, and so it is necessary to clarify exactly what the author of the current research paper understands it to mean.

Within the framework of the gospel understudy, the Messiah is identified with Jesus Christ; a synonymous sign is placed between the two. In Matthew’s perception, the Messiah is the Son of God who came into this world to make a great sacrifice for the salvation of all humanity. He is a spiritual leader who inspires people to do good deeds, and in doing so, he himself does good, even if the price for those deeds is the Messiah’s own self-interest. This is the context in which Matthew understands the Jesus he described in his lifetime: the holy man is the Messiah in a sense indicated and was sent down by God to deliver humankind from suffering. This is the paramount understanding, for it does not coincide with the perceptions of Mark and Luke. For example, Mark described Christ as a servant of the people, suffering and enduring, while Luke denoted Jesus as the high priest. Both of these perceptions do not fit Matthew’s feelings, who sees the Son of God as a rule through the prism of the Savior.

In support of the above argument, the wording that Matthew cites in his Gospel is evident. One such episode is the case of the salvation of the paralyzed man: Jesus only had to point out to the sick man the possibilities of “getting up and walking” for him to realize it at the exact moment (Matt. 9:6-7). This situation perfectly illustrates the apostle’s attitude toward Jesus: he is a mighty but merciful messiah. Furthermore, Jesus in Matthew’s description is wise, for not all words can actually save a person from sickness.

On the contrary, the Messiah knows exactly that healing is only possible when one is found to be sinless, and that is why the Savior does not simply cure the sick man but says that all his sins are forgiven (Matt. 9:5). In turn, it is evident that the power to forgive sins is not vested in ordinary people: instead, a good cure for sins is only possible by the will of God, of which Jesus is the messenger. Hidden in this chapter of Matthew’s Gospel is another important message whose epistemological analysis allows us to confirm the Messianic nature of Jesus. After the episode of the forgiveness of sins, Jesus meets Matthew, who was sitting outside (Matt. 9:9).

When the apostle invited Jesus into his house, one of the pressing questions was to determine why the Messiah was spending time with sinners despised by his own people. Matthew makes it clear that Jesus’ decision to spend time with such people was not motivated by sacrifice or patience but by a desire to save them as long as they themselves needed the Messiah (Matt. 9:12). As a consequence, Matthew implicitly shows that Jesus is to be seen as the Messiah who has a part of God’s authority on earth.

One of the most meaningful scenes in which the divine origin of the Savior is not questioned in any way is the episode of the Transfiguration of the Lord. Matthew writes that Jesus was transfigured over his disciples, and his face and silhouette shone in blindingly white light (Matt. 17:2). Jesus’s role as Messiah becomes even more evident when the parallel between Christ’s transfiguration and the observers is drawn. Seeing the metamorphosis of Christ is one of the manifestations of salvation, for, at that moment, the beholder is also transformed (2Cor. 3:17-18; Heb. 12:2).

Consequently, witnessing such a miracle helps the apostles to be transformed for the better through the abandonment of earthly attachments. When the Pharisees came for Jesus of Nazareth, he surrendered to them, not for his salvation, but the salvation of all humanity. Jesus is severely mutilated, stripped, and humiliated before his execution, but the Messiah endures it all as long as it is part of his global mission in this world, according to Matthew (Matt. 27:27-31). It is noteworthy that even in describing the mockery of Jesus, Matthew points out: “Hail, King of the Jews!” (Matt. 27:29). Although the Pharisees’ words in this passage are seen as a mockery of Jesus’ title, the use of this particular epithet reinforces in the minds of the readers (listeners) the idea of whom Matthew saw the Messiah to be.

Finally, it is well known that each of the gospels ends in a distinctive way; by examining the structure of this ending, one can gauge the evangelist’s overall view of what Jesus was sent into the world to do. For example, Luke writes about Jesus’ resurrection and ascension, but before that, he left an important message for his disciples (Lk. 24:49). This underscores the view. that for Luke, Jesus is primarily a holy man who is concerned about humans relationships and concern for his disciples. Mark does not talk about Christ’s after-death instruction, dwelling only on the resurrection and ascension — in this interpretation, the evangelist views Jesus as the son of God and something more than an ordinary man (Mk. 16:19).

In John’s gospel, Jesus’ death is not indicated literally, but the leitmotif seems to be the view that Jesus will yet return (Jh. 21:22). This is consistent with John’s notion that Jesus is both human and Logos. It is only in Matthew’s interpretation that Jesus is given an authority not discussed by the other authors. In the words of the Messiah, Matthew writes, “All authority hath been given unto me in heaven and on earth,” pointing to the infinity of Jesus even after his death (Matt. 28:18). The Messiah’s instructions to teach and help other nations underscores the globality of the Son of God as the Messiah who came one day to save all humanity, not just specific communities.

Consistency with Academic Sources

The academic community is characterized by a study of Jesus’ role as Messiah and the Son of God who was called into the world to make the Great Sacrifice. For example, Subramanian explores a particular theological approach to reading the New Testament that involves filtering evangelistic knowledge through the lens of cultural readings of various ethnic communities. Subramanian cites a passage from the concluding chapters of Matthew showing the divine role of Jesus. In particular, Subramanian quotes Christ’s words in which the latter actually confesses his Messianic identity before the judgment (Matt. 26: 64).

In his study, Johnson takes a similar view, often replacing Jesus’ name with the synonymous “Messiah.” For example, Johnson provides the following information in the notes section for the reader: “and though Jesus is a peaceable messiah in the passion narrative, Matthew forecasts violence upon his return.” The fact that the author casually points out the identity between Jesus and the Messiah makes it clear that Johnson’s perception of Christ as the Messiah is inherent.

Holdsworth’s Christological study of the genealogy of Christ is also accompanied by a clear agreement that there is no difference between the Messiah and Jesus: Holdsworth writes in the preface to his work that “Jesus is presented as… the Messiah, whose arrival at an auspicious time is about to set a new direction in religious history.” This reading also makes it possible to unequivocally accept the authors’ view that Jesus is the Messiah with a particular, measurable purpose for the New Testament.

In discussing the meaning of Matthew’s Gospel through commentary on specific aspects of it, Ward-Hall literally repeats the thoughts indicated by the author of the current research paper in the previous sections. In particular, Ward-Hall writes that Matthew’s purpose as a writer was to create an image of Jesus as the Messiah who came to save all humankind and to help the Jewish people in particular. Finally, of particular epistemological interest may be Novakovic’s book, in which the author focuses on the use of the image of the Apostle Mark in Matthew’s Gospel. Regarding Jesus, Novakovic explicitly points out in several places that for Matthew, Jesus is the Messiah.

Novakovic uses several specific episodes from the New Testament as arguments, which was typical of this research paper as well. Thus, a brief review of five independent academic sources reliably shows that each of them views Matthew’s perception of Jesus primarily as the son of God and the Messiah who came into the world for the salvation of humanity. This is a good indication of a proper independent reading of Matthew’s gospel and a definition of the dominant image of Jesus as seen by one of the first apostles.

Conclusion

To summarize, each of the four canonical Gospels reveals Christology from a particular perspective from which the Evangelists perceived the image of Jesus Christ. The focus of this paper was on Matthew as one of the chief apostles of Jesus and the first writer of the canonical book on the life and miracles of Christ. It has been shown that Matthew perceives Jesus as the Messiah, as repeatedly reported in twenty-eight chapters of the Gospel.

The paper reviewed the features of this book and showed that the primary audience for whom the apostle was describing Christology was the Jewish communities: it may be for this reason that Matthew seeks to portray Jesus as the Messiah since the theme of the messenger of God sent to save humanity is iconic to the Old Testament.

The third section of the research paper describes in detail why Matthew viewed the person of Jesus as the Messiah and gives examples that directly or indirectly support this argument. These ideas were formed based only on a careful reading of Matthew’s gospel. The following section discussed five academic sources (articles and books) that confirmed the author’s findings: each of the researchers proved that the perceptions of Jesus as Messiah are accurate Matthew.

Bibliography

Foster, Paul. “Harmonization in the Synoptic Gospels.” The Expository Times (2019): 37–38.

Holdsworth, John. “Family Trees: Who Is Baby Jesus?” Supporting A-level Religious Studies. The St Maryʼs and St Gilesʼ Centre 17 (2020): 2–41.

Johnson, Nathan C. “The Passion According to David: Matthew’s Arrest Narrative, the Absalom Revolt, and Militant Messianism.” The Catholic Biblical Quarterly 80, no. 2 (2018): 247–272.

Novakovic, Lidija. “Matthew’s “Messianization” of Mark.” In A Temple Not Made with Hands: Essays in Honor of Naymond H. Keathley, ed. Mikeal C. Parsons, Richard Walsh (Oregon: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2018), 15-26.

Rosik, Mariusz. “C. Mitch, E. Sri, Ewangelia według św. Mateusza. Katolicki Komentarz do Pisma Świętego.” Wrocławski Przegląd Teologiczny 28, no. 1 (2020): 363-365.

Subramanian, J. Samuel. “Tribals, Empire and God: A Tribal Reading of the Birth of Jesus in Matthew’s Gospel, Written by Zhodi Angami, 2017.” Biblical Interpretation 27, no. 3 (2019): 467–469.

Ward-Hall, Jane. What Faith Looks. The Kingdom of God, 2000. PDF e-book: 1–3.