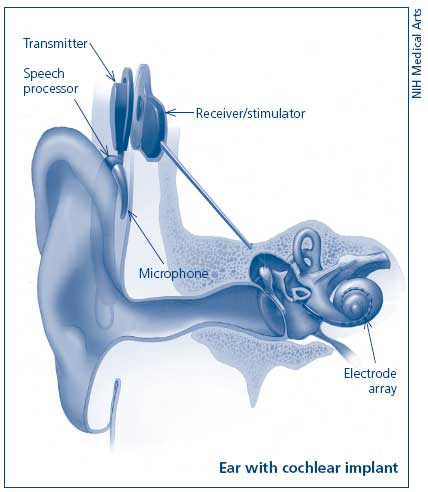

A cochlear implant is an electronic device that is used by the deaf or persons with problems of hearing. The device is usually implanted in the ear to ensure that one is able to sense sounds within the environment. The main components contained in the cochlear implant include a microphone, speech processor, transmitter and an electrode array (Clark, 2009).

The microphone receives various sounds from the environment and this is then transmitted to the speech processor which ensures proper selection and arrangement of sound. The transmitter helps to convert the sounds into electric impulses which are eventually sent to the various parts of the auditory nerve.

The purpose of having a cochlear implant is to provide hearing for the deaf persons especially those with affected sensory hair cells. It facilitates the understanding of sounds of speech in an appropriate way. Young children, who need special education, have been able to learn speeches and sounds by using this device. It facilitates the understanding of various environmental sounds by old people with hearing problems.

Cochlear implants work by stimulating the auditory nerve in a very complex manner. It generates different signals through the auditory nerve and then directs them towards the brain (Clark, 2009). The brain recognizes these signals and records them as sound. This process requires one to learn on how to detect and understand the environmental sounds after which he can comfortably hear them.

The current cost of the device ranges is about $5,000 and this may even go as high as $10,000. For the replacement of this device, it is done after every 10 years depending on the extent of its usage.

There are various costs associated with cochlear implantation which include costs before operation, costs during the surgery, post-operational costs, programming costs, daily expenses as well as the costs of rehabilitation. Preoperative costs may include medical expenses, other audio logical evaluations, costs incurred for a CT scan, and costs associated with the various trials carried out to check the hearing conditions of patients as well as therapy.

Other costs related to the surgical operations and procedure are those of acquiring the implant device, other related components supplied as well as surgeons’ fees paid by the patient. The costs incurred after operations can be very high in the process of programming which is usually done several times and the average costs incurred in may vary from one patient to another.

The risks associated with the use of this device include the requirements for shaving the hair cells before an implant is made and this may affect the hearing of the patient permanently.

The quality of sound is not as effective as the natural ear and young children may not understand some sounds as they need to learn on how to use it for a given period of time. The audiologists and language pathologists should be used at every stage during the learning process. Another risk that has been reported is that the operation involved may also damage the facial nerve.

Many researchers and scientists are looking for innovative ways of designing a very small device that can be implanted internally and even provide a very clear sound transmission.

The main manufacturers of the device are MED-EL, Neurelec Company and Cochlear Limited Company. The device has been supported by many deaf communities due to the benefits associated with its use. This has changed the lives of the deaf persons in understanding various environmental sounds (Clark, 2009). Due to the advancements in technology, the device is expected to solve problems of integrating it with the use of sign language.

Reference

Clark, G. (2009). Cochlear implants: Fundamentals and applications. New York, NY: Springer.