The research proposes to distinguish the competitive advantages for businesses to leverage the mindset acuity of post-9/11 era (10th September 2001- Present) military veterans in their recruiting, hiring, development and retention practices. The study also aims to focus on cultural aspects of their military mindset that present value to businesses. Post-9/11 era veterans and their intrinsic military skills acquired through encounters during the military transition to counterinsurgency campaigns and asymmetric conflicts, which directly emulate the transformation dynamics in today’s business environment. The study proposes the utilization of five themes identified in the context of the military mindset, which are organizational culture, leadership, discipline, resilience, and teamwork which can be used within non-military organizations to enhance various elements of performance or organizational structure.

Introduction

The goal of the study seeks to identify the military mindset qualities that post-9/11 veterans possess and its strategic advantages to businesses. The linkage of the military mindset and their application in business settings support the research and analysis of the selected research topic. According to Darwin’s Origin of Species, it is not the most intellectual of the species that survives; it is not the strongest that survives; but the species that survives is the one that is able best to adapt and adjust to the changing environment in which it finds itself (Megginson, 1963). Darwin’s evolutionary theory is an example of an inner logic that has wide cultural influence (Birkin et al., 1997), but the behavior of the most successful is seen as being opportunistically adaptive during environmental change (Baskerville, 2006). Therefore, the same principle can be studied to apply in a corporate setting since “Economics, business organisations, and capital markets were considered to operate as machines: inputs and outputs, controls and regulators.” (Bakerville, 2006). In modern conditions, many organizations operate in a turbulent environment and are forced to carry out constant changes to maintain their competitiveness. Veterans have highly developed command skills, which is another advantage for businesses (Benmelech and Frydman, 2015).

The competencies and characteristics of the organization’s leader must be sufficient to manage reactive changes. In this sense, the experience of post-9/11 veterans who have participated in military operations in Iraq such as Operation Desert Storm, and more recently in Syria, where the conditions for waging hybrid warfare have become even more complex, it is invaluable for developing organizational skills in business. The military training and experiences veterans receive are systematically known in building highly efficient, cohesive, and resilient organizations which are indicative of the Department of Defense (DoD) and their components (Active, Reserve, National Guard). In the post-9/11 era of regional and short-term deployments in global anti-terrorist efforts, veterans often find themselves entering the labor force, with the experience often highly valued by employers. SHRM Foundation article titled “Why hire a vet (2017)” states companies are learning that veterans offer a broad spectrum of skills and knowledge that can enhance small, midsize and large-scale enterprises. Post-9/11veterans add essential technical and interpersonal skills, discipline, leadership, loyalty, and many other attributes to a company’s workforce—all of which improve the organization and the bottom line.

The military mindset forged through years of service, training and subsequent high-pressure situations can have relevant applications in a corporate business environment which has become oftentimes stagnant, undisciplined, and without strong management or leadership at non-executive levels. The conclusion of this study will address the gaps of information that the research will identify.

Documentation

The literature search strategy sought to use a deductive approach of taking a broad theme and research topic of “leveraging military mindset into business” and narrowing it down to specific applications. For example, the practical applications of the military mindset were explored in the context of business leadership, business discipline, resilience in crises, or strong elements of teamwork. Using article databases such as Trident Online Library, Google Scholar, JSTOR, Scopus, Science Direct, ProQuest, and Emerald, key terms were searched for military mindset, organizational culture, corporate leadership, and articles selected based on relevance from a preliminary reading of abstracts. Articles were reviewed for subject matter, relevancy, as well as basic elements of efficacy and reliability. Approximately 156 articles, journals and books where examined, out of which 58 were selected for the literature review. Thematic analysis was conducted to categorize the articles based on subject themes in relation to the organization of the thesis and organization of the literature review (King et al., 2017). Based on this, a logical cohesive flow of information was written based on current available research.

Table 1. Categorization of Literature by Theme on the Topic of the Military Mindset

The deductive method of information retrieval will be applied, in which the process of cognition proceeds from overall generalizations presenting a general pattern, to single judgments and facts (Charniak, 2014). At first, general literature was reviewed to establish a base of the current state of research in leadership management research, then transitioned to finding literary sources of a scientific or methodological nature regarding military mindset. In view of the selected topic and the peculiarities of data needed for its analysis, the most suitable study design is action research. Action research has come to be understood as a global family of related approaches that integrates theory and practice with a goal of addressing important organizational, community, and social issues together with those who experience them (Bradbury, 2015; Brydon-Miller and Coghlan, 2014). The main goal of researchers dealing with applied research is to enhance human conditions, however the results of such studies may also bear commercial significance. By its nature, action research may be regarded as a mixed method since it incorporates both the process of doing research and the procedure of taking action about the study (Adams et al., 2014). In the originality/value statement, Kirchner and Akdere (2017) noted “A review of existing literature revealed little evidence of examining the military’s approach to developing leaders, even though employers claim to hire veterans because of their leadership abilities” (p.357). There exists a dearth of papers that consider military approaches for non-military organizations – such investigations are used to strengthen the project and provide some data for comparison and further study.

While there is a notable lack of literature, there are some insights provided on military mindset prior to the post-9/11 era. For example, Kirchner and Akdere (2017) identify four development strategies that can be applied in commercial training as well. Roberts (2018) highlights various principles of military traits that can be compared and contrasted with traditional business management styles. Deshwal and Ashraf Ali (2020) examine theoretical backgrounds that are relevant as well. Nevertheless, there are significant elements of information not found in these sources, particularly in the sense of more practical applications of the military mindset in a business environment. Earlier research is beneficial since the military mindsets tend to change very slowly due to the conservative nature of the organization. As mentioned earlier, many companies hire veterans with the emphasis of the military mindset, but how these are applied in the workplace and day-to-day or large project management is relatively unknown in the current scholarly literature. Therefore, it would be advantageous to study the current state of the military mindset in civil organizations.

The general conclusion from the inquiry is that while there is information on general theoretical practical and applied research for veterans’ transition into business and the leveraging of veteran’s experiences; explicit research or studies with the similar application to post-9/11 era veterans are lacking.

Constructivist

Throughout the literature examined for this research, one concept that is consistently appearing is that the military mindset and leadership qualities are learned (Adler and Sowden, 2018; Kirchner and Akdere, 2017). Ranging from lower ranks to commanding officers, regardless of branch or purpose, individuals are expected to command the military mindset skills that are learned through culture, training, resilience, and teamwork as discussed below.

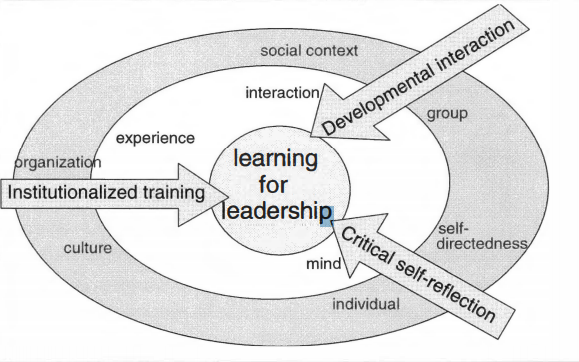

When applying this approach and standard to commercial organizations, a relevant theoretical framework is the constructivist approach to learned leadership training. In an era of leadership, learning and personal development are critical contributors. The constructivist approach seeks to identify constituent characteristics that involved in the development of competency, which may include psychological, social cognitive, behavioral, and message productional factors (Johnston, 2018). The constructivist approach emphasizes leadership development, effectiveness, and evaluation in how they perceive and perform their roles, as well as engagement in reciprocal processes such as learning, shared values and responsibilities, and facilitation (Yildirim and Kaya, 2019). Participating in the construction of knowledge, allows leaders to make necessary cognitive, behavioral, and practical changes regarding their role in an organization (Johnston, 2018). As seen in Figure 1 below, there are several approaches to acquiring knowledge and applying it to learned leadership. The critical constructivist approach suggests that the developmental synthesis of all these approaches are required to achieve expected results (Nissinen, 2001). At the individual level, there are mind-centered concepts such as self-reflection and self-directedness, while the organizational level encompasses institutionalized training and cultural frameworks (Nissinen, 2001).

The importance of the constructivist approach lies in its explanation of how learning takes place. Per Johnson (2019), it is an active process that requires the active involvement of the learner at all times. Knowledge cannot be effectively conveyed when one side imparts it and the other passively receives the information. The role of the teacher is to inspire curiosity in their student so that they start asking questions and trying to understand the topic in earnest. The learner, in turn, needs to understand the importance of what they are learning and be committed to obtaining the skillset that is discussed in this paper. To that end, it is essential to gather evidence of the effects of a military mindset on business performance and link the two together in a compelling narrative. This paper is a step toward that goal that aims to compile and process the relevant information.

It is also vital to differentiate between the two approaches to constructivism that have been formulated over time. Johnson (2019) claims that these are cognitive constructivism, which is the theory described above, and social constructivism, which posits that one’s learning is influenced by their social context. As such, the teacher’s role would be to encourage social interaction and provide a cultural context to the subject being taught. However, for a number of reasons, social constructivism is less appropriate for the topic discussed in the paper than its counterpart, which has led to its rejection. The military is not necessarily easy to accurately explain in a cultural context, in large part due to its frequent misrepresentation in popular media. Creating a social environment that reflects the military is also a challenging task, which is the reason why cognitive constructivism fits this paper better. With that said, it is possible to borrow some elements from the theory, such as the requirement for organizational culture adjustment.

Applying the constructivist approach to the research question presents an opportunity to explore how the learned military mindset can be applied in business settings. Similarly to the military organization, the elements of said leadership and mindset can be learned if there are appropriate resources and culture in place as well as influences which promote critical self-reflection (Hilden and Tikkamäki, 2013). In that environment, it is possible to apply both cognitive and social constructivism, as the learner experiences the military culture and interacts with more advanced leaders while also exhibiting an interest in learning the method. The military mindset is achieved through a multifaceted constructivist approach, where a combination of culture, experience, interaction, and individual growth contribute to the development of the valuable characteristics. The key question becomes on how to transition that learning model to a commercial environment to achieve similar mindset in leaders and employees.

Schein Model of Organizational Culture

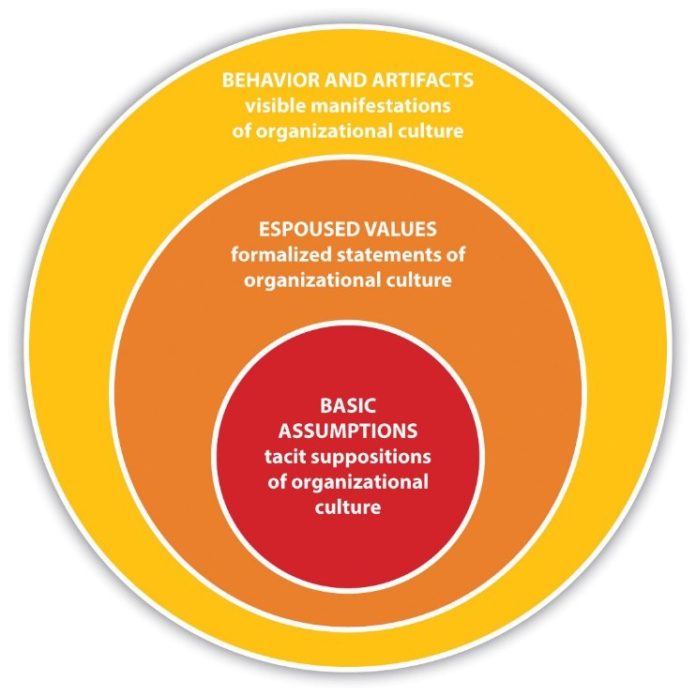

Organizational culture is a commonplace term which typically encompasses the values and beliefs in an organization which ultimately impact its principles, ideologies, and policies. Edgar Schein proposes that organizational culture takes significant time to form and develop as employees and leadership undergo changes, adapt to external environments, and solve problems. The Schein framework proposes that there are three levels of organizational culture: 1) Artifacts, 2) Espoused Values, and 3) Basic Assumptions (also known as assumed values) (Schein, 2016). Artifacts are characteristics of an organization which are evident and easily perceived, everything from dress code to facilities to public vision. The values are the values of the individuals working in the organization, as over time, thought processes an attitude make a deep impact on the culture and workplace environment. The mindset of individuals associated with an organization, influences the culture of that workplace. Finally, assumed values are those that cannot be measured and stay hidden, but continue impacting the culture – inner aspects of human nature. This may include attitudes such subconscious racism or sexism, or even practices which are never discussed but remain an open understanding within an organization (Schein, 2016).

The application of the military mindset in business has to take into account these numerous levels of organizational culture. As later discussed, some elements in the military culture are similarly publicly seen and discussed, while others are tacit and develop with years of focused teamwork, culture of respect, and the discipline and resilience which define the mindset. Therefore, transitioning the mindset into commercial settings will also take time to develop the culture from initial workplace rules and public vision to the underlying understanding that the organization is a team which strives towards a common objective. Some of it may be counterintuitive to the common business practices of competition and self-centered individuality, but over time, with layers within this framework, the military mindset can be adapted.

With that said, the drawbacks of Schein’s model need to be taken into consideration throughout the discussion of organizational culture. Overall, the concept is nebulous and challenging to describe because organizational culture tends to develop spontaneously and be challenging to observe or manipulate. As Gilbert et al. (2018) note, the model provides an outsider’s overview of an organization’s internal culture, focusing on the outward expressions and artifacts that may not necessarily be accurate. The example they use is that, while an overwhelming majority of all businesses claim they value safety, this commitment does not necessarily manifest in practice since the underlying organizational culture does not promote this value. Users of the model need to consider this potential discrepancy and factor it into their observations when attempting to judge an organization’s culture, gathering as much information as possible and trying to obtain a multifaceted perspective.

It is also necessary to consider that organizational culture is flexible and mutable, changing over time as the organization adapts to new needs. Campbell (2019) discusses a recent post-Cold War evolution in the American military mindset, which had traditionally been focused on conventional warfare and the application of direct force on the battlefield. However, this strategy proved fruitless in environments such as that of Vietnam, and senior leaders went against the established culture by considering non-conventional approaches and applying them in practice. As a result, counterinsurgency (COIN) operations became part of the standard American military protocol despite going directly against the culture at the time (Campbell, 2019). This warfare doctrine also required a shift in army leadership approaches that would make these smaller-scale, more precise operations possible. As such, both the military’s culture and its approach to leading have changed over time and are likely to do so again in the future, which means it is essential to rely on current information for accuracy.

Leveraging the Military Mindset

The Military Mindset

The military mindset, initiative, adaptability, flexibility, innovation, and creativity are necessary for the survival of personnel in wars/conflicts and the survival and development of their organizational culture. Adapting is just as essential to survival in business as on the battlefield and many businesses do not survive over time because they fail to adapt to changing business conditions (Burns, 2013). Solving problems using the out-of-the-box approach is necessary for the military culture and currently applies to every business unit. An argument that military service and combat activity of servicemembers requires a complex of certain qualities, which, forming the professional structure of one’s personality, at the same time represents the basis of leadership in a team. The most important of them are high intelligence, purposefulness, ability for psychoanalysis and reflection, resistance to stress, emotional balance, ability to manage oneself, empathy, organizational insight, exactingness, professionalism and sociability. Kiyosaki, the author of 8 Lessons in Military Leadership for Entrepreneurs, argues that men and women in the military have unique key skills and backgrounds for entrepreneurship and in many cases, are prepared to do the impossible. According to a Bentley University study, nearly three-quarters of hiring managers complain that millennials — even those with college degrees — aren’t prepared for the job market and lack an adequate work ethic (Pianin, 2014). By their nature, post-9/11 veterans trained to do the impossible – and are willing to pay the necessary price (often called the ultimate sacrifice) – are strikingly different from those who are taught to seek high-paying jobs with a good package of benefits.

Work organization and labor division have changed significantly, leading to more people who focus more on the outcomes based on adequate knowledge and research (Lyskova, 2019). Under the knowledge economy, the focus is to understand how experience and education, which is “human capital,” acts as a business product or productive asset to be exported and sold to create profits for the economy, businesses, and individuals (Gregg, 2018). This aspect of the company depends on people’s intellectual capabilities and not physical contributions or natural resources. Considering the differences between success in the civilian world and in the military, it may be questioned whether business success requires the same core skills, values, and leadership qualities that are formed in the military. To answer that question, it is necessary to understand the specific differences between the two environments and the challenges that leaders face in each case.

The primary difference between the civilian and military environments lies in who they are responsible to. Private businesses serve customers, who can take a variety of forms, while the military answers to elected politicians. As a result, it has adopted a conservative attitude that emphasizes the unpredictability of the future and the need for the organization to rapidly and effectively respond to changing circumstances (Maurer, 2017). Conversely, while the future is also unpredictable in the private sector, it is still possible to forecast demand for products, and disruptions are rare. With that said, the military ability to create robust organizations and handle crises can be invaluable for businesses since, despite their rarity, such events can have catastrophic effects on the organization. Therefore, it seems expedient to investigate the possibilities and potential benefits of attracting the post 9/11 military veteran mindset into business organizations, with the aim to improve leadership practices, talent management, and, as a consequence, organizational performance.

The last significant determinant of the military mindset is the exact relationship between the army and civilians. As Corbe (2017) notes, while at the top level, the army is subordinated to the civilian sector, at the operational level, the relationship is not as hierarchical and is also poorly understood. The military is a tangible entity that exists within the nation as well as abroad and interacts with others. It often becomes involved in local initiatives, where the two sectors help each other solve their issues and improve the quality of life. The families of military members also have to be considered, as they can often form substantial communities in and of themselves. As a result, while military members are used to their local culture, they are not ignorant of the broader culture of the civilian locations around them. Barring complicating factors such as an extended foreign tour, adaptation to their new conditions should not be excessively challenging.

Organizational Culture

The United States (US) military is considered a unique organization with the inherited responsibility of protecting and defending the US and its interests. From the military inception during the Revolutionary War, the military has acted, fought, and thought differently. It takes a particular type of individual to place the needs of the country over self. Since the beginning of military service, these differences, which focus on achieving the mission in unorthodox and unique ways, have become the basis of the military culture. It is a crucial aspect that makes the military successful in accomplishing difficult missions in extreme situations. The military offers vital lessons for business leaders, and mostly leans on the power of the organizational culture and how to drive success. Sullivan et al (1997) stated “we have found more and more business leaders seeking out the Army, looking for leadership ideas and learning”. These mindset changes are not easily undertaken in a business, but the successful leverage of a similar culture can ensure a competitive advantage. A strong organizational culture is a common aspect of successful organizations. Many agree that the topmost of the company’s goals is to have the right cultural priority. A company needs leaders who understand and appreciate their cultures and are ready to do whatever it takes to ensure employees understand its cultural identities. These organizations have clarity about their values and the way the values define their companies and operations.

To understand the military culture, it is first necessary to analyze its origins and the influences that drive its changes. As Ruffa (2018) highlights, the military is beholden to civilian decision-makers who decide where it should be deployed and to what purpose. At the same time, it is expected to conduct its operations efficiently and with minimal damage both to itself and to the people not involved in the conflict. Through policymakers, the military is also involved with its nation’s public, which can support or oppose the usage of force. These views would then be reflected in the political climate, whether through the nation’s leadership changing its stance on issues or new politicians being elected. The military has to take these changes into consideration while conducting its operations, which creates a multifaceted network of issues. Hadid (2021) provides an example with the recent US move to leave Afghanistan, which was done at the behest of the public and the nation’s leadership but leaves the nation at risk of being overrun by the Taliban. In this case, balancing the demands of the military’s superiors and the lives of the civilians that the Americans were protecting has proven to be challenging and potentially impossible.

Another vital consideration about the military is that it is intended to be a tool that the nation’s leadership can use to achieve strategic objectives. To that end, it is granted the exclusive right to use massive force that, in most nations, completely outclasses the tools available to civilians. This power is ripe for abuse, as the many military coup d’états throughout history have shown. Even without the active and unlawful application of force for such ends, the military can exert substantial influence in a nation’s politics, whether through making budgetary and other policy demands or more unethical means. As such, it is the duty of the military to use its power responsibly and abide by the numerous restrictions that have been placed upon it. Per Maurer (2017), the expectation is for it to not become involved in politics and contain itself to the fields that are its direct responsibility. To that end, it is necessary to create many robust organizational safeguards that prevent misconduct early on before it can manifest.

The success of changes in today’s military rests with the distinct culture and the transformation to an asymmetric warfare and near peer approach. Post-9/11 soldiers possess a unique mindset acquired thru transition to asymmetric warfare, where the social, cultural and political dimensions parallels today’s business environment. The unique culture is the dedication to achieve the mission and the unconventional approaches used to solve problems. Although some argue that “the values do not focus on the people but focus on the company and its objectives” (Felipe et al., 2017). These key cultural traits are shared across the DoD enterprise, regardless of the mission, rank, unit, or related factors. Culture is organic and intangible and has given various leaders, officers and enlisted, the management tools they use to influence culture, including rigorous assessment and selection, complex missions, strong leadership, and training processes. Like every successful organization, culture is integral to the military unit and how it achieves its mission.

With that said, the military organizational culture is not necessarily the best example to follow for civilian organizations in some regards. As was mentioned above, military culture often tends to be static, waiting for internal actors to reform it while also passively rejecting any such attempts. Breede (2019) highlights this issue and recommends that the army regularly revisit its organizational culture to ensure that it matches the evolution of social discourse, with the assessment preferably done by non-military personnel. The overextensions in which the army engaged after 9/11 serve as an example of the issues that can manifest should the military be able to act without constraint or self-reflection. Action needs to be taken to ensure that it can constrain itself, whether with external help or without it. The mechanism would both improve the military’s current organizational culture and reduce the chances of it deteriorating over time.

The military mindset begins with the organizational culture, something that business leaders can learn and embrace to ensure their companies achieve optimal performances. In the military, accomplishment of the mission and training shape the culture, thus the same applies to business organizations. Their mission and training can shape culture and influence organizational performances. Selecting is about finding the right individuals and also molding them to the common culture. Across the military, no matter the specific service or component, the culture is one where one does not quit until the goals or mission are achieved. It is not about finding the best people but more about finding the right individuals. It is about finding the right individuals who have the right key competencies and are trainable. A case of consideration is the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks. The training and assessment plans prior to 11th September 2001 still have the same people, but the military culture and mindset were immediately able to adapt to a new phase of warfare. The persistent ability of an individual or unit to constantly sense its environment for change and to agilely respond to actual or anticipated changes in the environment in a way that improves its operating effectiveness or survival in that environment (Burns, 2013). The military looks for intense dedication from teammates with a strong desire to succeed in an ambiguous environment, and individual fortitude. In the book Hope Is Not a Method: What Business Leaders Can Learn from America’s Army, Sullivan et al (1997) stated “Like any business, the military constantly search for high-quality people and strive to effectively train, motivate, and retain them. These individuals are what the military seek, and are also highly desirable in business.

Leadership

The military is known for stimulating and developing leadership qualities in servicemembers. As a result, many military veterans pursue management roles in organizations or begin as entrepreneurs. Several studies introduce the idea of using military leadership practices in non-military organizations to improve their performance. The main argument put forward by Bungay (2012) is that there is the task to analyze the possibility of building synergy between management, leadership, and command, in which the experience of military veterans who took part in hybrid wars, can become valuable, helping to introduce in business organizations best elements and practices of military leadership. One of the more recent investigations written by Kirchner and Akdere (2017) explores the possibility of using military leadership development tactics in commercial training. The authors suggest that some traits of military leadership development can contribute to human resource training. In particular, Kirchner and Akdere (2017) highlight the establishment of core values for all employees and a dynamic supervisor-employee relationship. Roberts (2018) presents the twelve principles that should guide modern military leadership, describing such concepts as leading from the front, having self-confidence, fostering teamwork, being decisive, and others. This recollection of necessary traits from a person with actual command experience can be used in the present project as a foundation for the military leadership theory to be integrated into the corporate setting.

It should be noted that, despite appearances, military leaders do not rely solely on their authority and right to give orders in their work. Stebnicki (2020) states that reliance on an authoritarian or even a transactional leadership style in the military does not produce benefits beyond the short term. Those who succeed in their positions will typically listen to their subordinates and accommodate differences of opinion among their subordinates. With that said, they will also be ready to act quickly and decisively when the situation calls for it, expecting the people being given orders to obey immediately. This duality of approaches is vital to the success of the military as a force that is ready to act at any time but also an organization that needs to sustain itself in peacetime.

The military provides individuals with key skills needed in leadership, some of which are discussed in other themes, such as the ability to overcome obstacles, teamwork, weighted risk-taking, and discipline. The spirit of military mindset can be replicated in team spirit and solidarity in business environments where the individual is able to take the leadership role (McDermott et al., 2015). The military uses a continuous and consistent approach to leadership development, expecting competencies from all its members regardless of actual position or authority. However, those in positions of power in the military have much more consequential roles, where mistakes can cost lives of soldiers as well as national security risks for civilians. Therefore, development of leadership competency through the synthesis of knowledge, skills, and abilities is a holistic model of development that can be applicable in non-military organizations as well (Kirchner and Akdere, 2017).

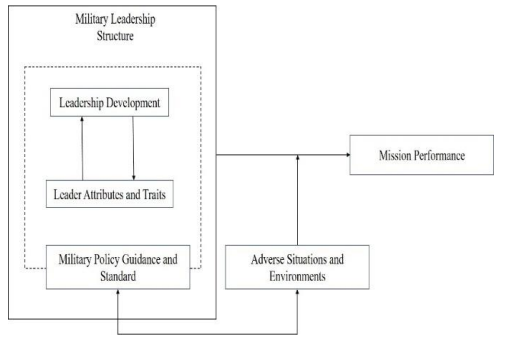

Nazri and Rudi (2019) proposed the military leadership framework seen above. They argue that leader paradigms continue to emphasize attributes and traits which are crucial in key settings. Furthermore, military leadership commonly follows guidance, doctrines, standards, and principles which are regularly updated, allowing for development and innovation. These changes often come from within the organization, as demonstrated by the COIN example above, and, while innovation is sometimes stifled in the military, it is also adopted once it shows its effectiveness. Many of these traits are effective in complex, dynamic environments which can be seen in the business context. Qualities such as confidence, adaptability, emotional stability, intelligence, decision-making and competence are crucial for leadership organization in virtually any context. They are promoted in the military with substantial effectiveness, especially considering the turnover system that exists in the sector.

A remarkable aspect of military leadership lies in its lack of dependence on individual leaders. According to information gathered by Castro (2018), the average military leader stays in the same position for two years or less before departing. As such, transitional periods are frequent, and the military has to be able to handle them effectively to remain a competitive force. This tendency is substantially different from that demonstrated in the private sector, where, especially at smaller companies, a leader can stay in the same position for periods that can last for decades. With that said, it also means that military leaders are used to taking stock of a situation quickly and devising an action plan. This quality can be invaluable for situations where a leader needs to be quickly introduced to an environment to make changes. With that said, the ability of military leaders to operate in the long term needs additional investigation.

The military does necessarily promote long-term planning beyond its highest leadership, which is expected to maintain parity or superiority with current and emerging threats and be prepared for a number of theoretical scenarios. However, these leaders are long-term army people who are unlikely to leave their positions to take a job at a private company. For the lower-level personnel that is considered in this paper, the primary focus is the accomplishment of the mission at hand in the most effective manner possible. However, the military is aware of the issues related to the short-term orientation this tendency can create and has stringent policies in place to relieve leaders who manifest this type of misconduct of their duties (Szypszak, 2016). As such, there is some expectation of the military leaders to be able to operate in the longer term, though the competence is not necessarily being actively promoted and reinforced.

Overall, while exclusive training in military-style leadership is likely not sufficient for success in a civilian environment due to the different purposes and divergent evolution of the approach in the two sectors, it can serve to complement more conventional competencies. Currently, there is little overlap between them or understanding of how military styles enhance private-sector leadership (Kirchner & Akdere, 2017). However, it stands to reason that the application of some of the competencies military leaders learn to civilian environments can be beneficial for the organization in question, especially in situations where change is required. For the specific application of hiring veterans, it may be reasonable to have them undergo a civilian leadership training course to ensure that they possess both sets of competencies. With this knowledge, they would be able to perform well in their duties and demonstrate the strengths of the skills they learned at the military without undermining the organization’s performance.

Discipline

One of the most recognized military traits is discipline, which also has a fit in the context of corporate business. Discipline brings with it a mindset which is objective-oriented but also organized and the ability to persevere through difficult or tedious tasks. While discipline is not unique to military, it is often placed at a high priority. Discipline is a key element for both leaders, which have to exercise patience and control, and for basic workers and low-level managers which have to demonstrate discipline in fulfilling remedial tasks and wait for opportunities to climb within an organization (Georgiev, 2019). Discipline is a foundation to multiple other aspects of leadership and military mindset which are discussed in this review.

Military discipline is centered around hierarchy, with strict chains of command and severe punishments for not following orders. One is expected to obey their superiors unless their order involves clear violations of the law, such as firing at civilians or committing fraud. The decision to follow the order is not contingent on what one thinks of the person giving it or of the order’s effectiveness. It is assumed that a superior has access to more information than a subordinate and makes better decisions. As such, the desire not to follow them can only stem from personal incompetence or lack of access to crucial information. The superior is not obligated to provide this information, as in doing so, they would be wasting valuable time. In disobeying, the soldier takes a substantial risk unless they can conclusively prove to a military tribunal that the order was unlawful.

This consideration does not necessarily apply to a civilian context, where no such chain of command is present. Subordinate questioning of the leader’s decisions is not frowned upon but rather expected and encouraged in most environments. Moreover, there is typically no time pressure such as that present in the military, and it is possible to convey the rationale behind every choice and receive feedback in time. Moreover, as Kolb (2018) notes, questioning the decisions made by politicians forms the cornerstone of political theory, which also alleges that the exercise of authority is a violation of the human right to moral autonomy. As such, the military approach appears to effectively be impossible to apply in a civilian context. Moreover, its effectiveness and sustainability within the military itself also have to be questioned.

While the unconditional following of orders in a military context may appear to be impossible to maintain given these considerations, the type of people who enter the military has to be considered. Every member of the military has entered it willingly with the expectation of finding this variety of discipline and the knowledge of the hierarchy’s existence. The premise of the military is that soldiers will have to follow orders that put them at risk of injury or death. As such, they are ready to obey directions on lesser matters from their superiors without question in most cases, which enables the style of leadership that is used in the army. They willingly consent to the removal of autonomy options such as the ability to sue the army, which some critics consider excessive (Chemerinsky, 2016). It follows that they would be ready to follow most orders in a manner that is entirely unlike that in the private sector.

It should be noted that in recent years, this aspect of army discipline has been undergoing a period of turbulence, at least in the United States. As Weber (2017) notes, while commanders can punish acts considered harmful to “good order and discipline,” the term’s definition is unclear and has been shrinking recently (p. 123). Discipline is increasingly being viewed as a relic of the past that the military holds on to as a means of resisting reform rather than a key quality that is essential for its success as an organization. It is currently unclear what the ultimate effect of this shift will be, but for now, it can be said that army discipline is more lenient than it used to be. Whether that is a positive change remains to be seen, and former military members will still exhibit substantially higher discipline levels than their civilian counterparts on average. However, this change has to be taken into account in the longer term.

The potential unconscious expectation of military leaders for this tendency to continue after they leave the army can be both beneficial and harmful for businesses. The leader will be used to quickly making informed decisions and putting them into practice, which can be helpful for the business’s flexibility. When rapid and large-scale organizational change is necessary, this willingness to create change can be invaluable. However, in other situations, this application of authoritarian leadership may be actively harmful. The leader can be wrong but also resistant to receiving feedback due to their lack of training in doing so. They can also arouse employee resentment through not interacting with them enough and giving too little consideration to their opinions. As such, it is necessary to ensure that a military leader is also competent in methods applied in the civilian environment before they can be fully trusted to lead.

Discipline is beneficial in bringing focus and attention to a business environment. In complex, shifting environment and market where a business operates, it is impossible to cover everything, so discipline allows a focus to be placed on the important elements which will ensure stability and growth for the company. Discipline helps in maintaining order and reducing panic in challenging situations, as well as adapting to the difficult changes if a company has become more efficient and cut costs. A disciplined figure can influence positive corporate actions and impact the organization in a manner which adheres to the best values and principles of business law and ethics (Nasih et al., 2019). Disciplines in military servicemember creates an individual that demonstrates critical professional thinking, but also maintaining creativity and independence, fostering intellectual development.

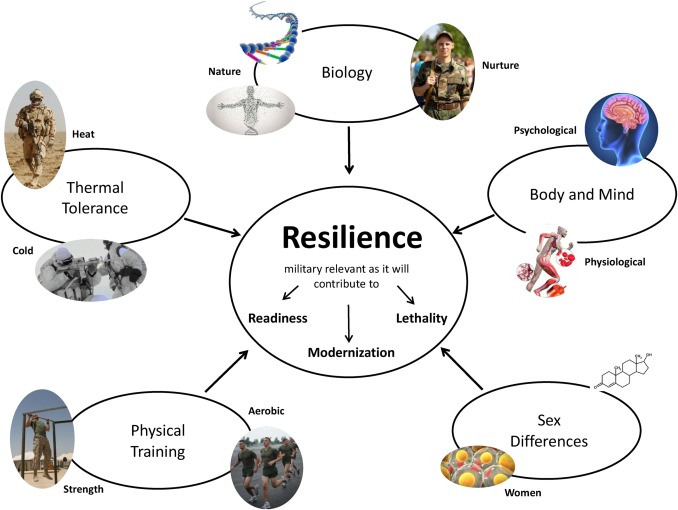

Resilience

The military mindset leads to formation of resilience, a key to survival in warfare contexts, but also creates character traits of adaptability and psychological strength that continue to remain useful in civilian life. However, resilience is the interaction between personal characteristics and the structural environment in which a person operates (McGarry et al., 2017). The military fosters a culture of resilience through its customs, traditions, and values. Resilience is also taught as part of military education, based on the cognitive-behavioral model. Transitioning from military to civilian life, resilience has both positive and negative impacts. While it may benefit an individual by providing strong core values, organizational skills, adaptability, and efficiency – negative elements such as the inability to emotionally adapt or shutting out traumatic experiences can cause psychological harm (Adler and Sowden, 2018).

The military is expected to be ready to engage in war at all times, which involves endangering its members and the stress associated with such an endeavor. Even in times when there is no active war, there can be political and other tensions that are apparent to soldiers and leads them to consider the possibility of deployment and combat. To that end, resilience is a vital quality that leaders are expected to both possess and teach to their subordinates (Matthews, 2020). The recognition of this need and the competencies that leaders can be taught to help them in the endeavor is a relatively new development in military psychology. However, the need for commanders to maintain physical and mental combat readiness in their unit has been known for decades, if not centuries or millennia, and each military commander will have a personal approach to doing so.

With that said, despite the military’s best efforts to promote resilience, it is not always successful in doing so, especially in veterans who have engaged in active combat. Post-trauma stress disorder (PTSD) is a well-known military issue that complicates the individual’s reintegration into society as they leave the military. Military leaders are no exception, and the potential for them to have the condition and suffer the associated difficulties have to be considered. Notably, Kramer and Allen (2018) investigate the habits of military leaders with PTSD and find that their usage of the transformational leadership style declines on average, though the effects are inconsistent and result in increased applications of the method for some individuals. With that said, the other symptoms of the condition also have to be taken into account. Company leadership can be stressful, and, though veterans with PTSD should not be denied the opportunity to engage in it outright, their ability to do so needs to be analyzed thoroughly, and some accommodations likely will have to be made.

With that said, while PTSD is a critical mental health concern, it is not overwhelmingly present in former military leaders. Many former soldiers, especially in the US, have never been on a tour where they would have a chance to develop issues. Moreover, Isaacs et al. (2017) find that of a substantial sample of US military veterans, 67.7% were mentally resilient. A large proportion was never exposed to powerful trauma during their conflict exposure and did not develop mental health issues as a result, but another substantial sample has been exposed to harm and overcome it with time. The factors that caused them to be able to do so are dependent on personal traits such as extraversion, emotional stability, gratitude, altruism, and endorsement of purpose in life (Isaacs et al., 2017). The figure may be indicative of the military’s overall effectiveness in fostering resilience among its members, though there is still substantial room for improvement.

It should be noted that, while resilience in the military context and its effects have been well-researched, the same cannot be said for its application to civilian life. As Cox et al. (2018) state, while most studies have focused on the positive effects of the ability to adapt and cope that is granted by resilience, it can also instill military attitudes that complicate adaptation to civilian life and are difficult to excise. Leaders, in particular, who have found some degree of success in the military, may become stuck in their ways and refuse to reflect on themselves despite facing difficulties in their new environment. With that said, the literature on the topic is limited and inconclusive, and more research is necessary before any definitive statements can be made.

A more competitive company has resilience and ensures workers cooperate in meaningful ways (Popkova, 2019). Military resilience can be defined as the capacity to overcome the negative effects of setbacks and associated stress on military performance and combat effectiveness support. Organizational resilience of the company and its members is a key trend in management practice recently. Williams et al (2017) proposed a framework that focuses on the themes of crisis and resilience. When integrating resilience into organizations, it creates capabilities of durability, organizing and adjusting, competent response, and strong self-analysis through feedback. The interaction between crisis and resilience is a dynamic process which requires the leadership and mindfulness to navigate (Williams et al., 2017). Integrating the concepts of military resilience in civilian organization contexts can be highly valuable from a mindset standpoint as they bring the capabilities listed above and navigate dynamic crises.

Teamwork

Military culture is distinguished by a profound commitment to a larger goal, often resulting in individuals putting their desires on hold. The culture and perspectives are inherently collectivistic and built around the concept of group-think and teamwork to support each other and achieve the set objectives (Adler and Sowden, 2018). Teamwork and collaboration have become a central element of the workplace and the use of teams is projected to increase. Businesses invest millions into training of enhancing teamwork effectiveness since successful teams produce effective outcomes in a wide range of contexts due to the team competencies and processes (Lacerenza et al., 2018). The military or other industries heavily reliant on teamwork for function or survival can achieve the strong and cohesive teamwork due to culture and methods of training and discipline not seen in typical office workplaces.

The importance of teamwork in the military is underscored by the areas in which it is applied and the stakes involved. By definition, military operations involve lives that have to be preserved or eliminated, and the two objectives often collide to create high complexity. Stanton (2018) provides the example of Iran Air Flight 655, where a team communication failure led to an attack on a passenger plane and 300 civilian casualties. Such mistakes are relatively easy to make but also devastating to the popular opinion regarding the military as well as its fundamental mission. To avoid these failures, the military has had to develop a well-organized teamwork system throughout the organization, with quick and efficient communication as well as the understanding of shared goals. It has engaged in a dedicated effort to overcome various teamwork barriers and maximize effectiveness.

As a result of this effort, teamwork stands at the center of the military’s values alongside hierarchy and discipline. Squads are capable of working together to an extreme degree in the execution of missions, with the members trusting each other with their lives. Perrewé and Harms (2018) highlight how teamwork may at times supplant the other two values, with the ranks of platoon sergeant and platoon leader being approximately equal. The military is effectively a nested structure of teams of progressively increasing sizes, with leaders of one layer forming a team for another and ready to coordinate the forces under their command with a high degree of precision. Moreover, they are ready to meet with people for the first time and immediately begin working together for the purposes of a particular mission. As such, the accident described above serves as an example of the military’s failure, but the fact that it stands out underlines how in an overwhelming majority of similar cases, the outcome of the teamwork has been successful.

The military’s understanding of the critical importance of teamwork has led it to develop approaches for improving it at a rapid pace. Its rapid progress has served as the inspiration for a substantial volume of teamwork research, as the army has been able to achieve an extremely in-depth understanding of the topic. Goodwin et al. (2018) note that over the last 60 years, research into the military’s teamwork system has been responsible for a number of crucial contributions, such as the importance of cognitive processes and multiteam systems. With that said, both the military’s advancement of its methods and the research into its success are still ongoing. Substantial improvements can still be made, and the modeling of the mechanisms that underpin the effort is incomplete. Military leaders can take their implicit understanding of these teamwork capabilities and implement them at their new workplace.

As a result of this effort by the army, former military personnel is capable of outstanding teamwork, whether they are in leadership or subordinate positions. Yanchus et al. (2018) confirm this expectation, stating that veterans are excellent at teamwork and also dedicated to the organization’s mission but report low satisfaction as a result of favoritism and unfairness. A military leader can help solve this issue, as they would be familiar with the issues and concerns of veterans. As such, they would combine the military excellence at teamwork with the ability to utilize the competencies of an often-underappreciated group to a high degree. They would also be able to take advantage of the various synergies that are employed in the military and potentially teach them to other employees through their examples. Ultimately, the potential exists for the achievement of efficiency beyond what conventional companies can achieve, though it needs to be managed carefully to fully manifest.

Lastly, the element of trust needs to be considered, as it is another vital quality for which the military is renowned. In high-intensity operations that require quick decision-making, it is vital that team members can rely on each other and trust them to perform specific duties with competence. Trust can also help team members mitigate stress, as they are aware that their group is greater than the sum of its members and can overcome obstacles that would not be manageable without their teamwork abilities. Moreover, the army is constantly researching trust and arriving at the frontiers of knowledge about it and factors that influence it, such as mood (Stanton, 2018). Military leaders who come into the workplace can leverage their superior knowledge of trust, both in theory and in practice, to foster it in their organization. In doing so, they may be able to enhance their team’s performance dramatically and set the groundwork for further improvements.

It should be noted that, as in many interpersonal fields, the research regarding teamwork, especially its applications in the military, is inconclusive. Many phenomena still remain underexplored and poorly understood, though their justifications in terms of terms of common sense seem to be apparent. As a field with some of the most advanced teamwork in the world, the military is particularly affected by this phenomenon. Overall, as Salas et al. (2018) note, bridging the gap between theory and practice is among the most significant challenges facing researchers at this time. With that said, while military leaders may not have a theoretical understanding of the methods that they apply, they are still able to successfully put them into practice. In this sense, bringing them to civilian workplaces can be particularly helpful as they can provide unique inputs, though it is challenging to evaluate the effects precisely.

Some key elements that can be adopted from the military models are trust and familiarity. Despite the hierarchical structure of the military, the individuals within teams as well as the chain of command have a number of informal interactions and set of linkages. With time, one becomes acquainted with the teammates due to the intimate knowledge of their behavior and actions, resulting in organic cohesion and teamwork. This leads into trust, as teammates trust each other with time, but leaders also demonstrate trust by placing responsibility on the teams and trusting them to function on their own. There are expectations and reputation, but trust is vital as it allows to rely on your team members, whether it is a nighttime raid which can cost casualties or a major office project that impacts everyone’s professional career. However, the military more often than not operates day-to-day functions that are mundane, and the lessons can be transferred to the commercial sector, which consist of basis factors such as building relationships and understanding team capabilities (McGinn, 2015). The military has succeeded in areas such as Afghanistan, Syria, and Iraq not due to the new weaponry systems or special equipment but due to the readiness to include any external organization, individual, or entity that will help accomplish the mission. This is the idea of adjusting all excellent power competition. It is the learning language of the organization. Business leaders can explore the different strategies used in the military to ensure successful and covert operations.

Summary

The military mindset can be used to ensure organizational success, especially in the modern competitive environment. At the center of a company’s culture are commonly held and shared values, therefore businesses must decide on the values they emphasize, including outcome, people, team orientations and focus on detail. Although it is argued that military train skills that are necessary for public companies, such as prioritization of tasks, confirmation of objectives understanding, observation of competitors actions (Stettner, 2019). The author of the book “Combat Leader to Corporate Leader: 20 Lessons to Advance Your Civilian Career”, Chad Storlie (2018), based research of military veterans, advocates the view that military veterans create substantial business results. Researchers also present supporting studies showing that veterans are 70% less likely to engage in corporate corruption and are more capable of making tough decisions (Benmelech and Frydman, 2014). The military mindset can contribute strongly to enhancing the corporate business environment.

Post-9/11 veteran’s experience and military mindset can benefits businesses by being able to make critical decisions in high-pressure situations and a strategic approach to long-term objectives as well as bring a level of strong leadership that garners respect, but promotes camaraderie. Discipline and rigor are beneficial since bringing these individuals and business practices aids in better structuring and organization within the structure – offering once again a systematic approach to problem-solving and processes, eliminating redundancies and improving efficiencies. Resilience is needed in business just as much as the military as it aids in overcoming challenges and being able to flexibly navigate the multidimensional situations that may arise in market circumstances. Finally, teamwork helps to better communication, enhanced workflow, and socially motivational aspects towards a common objective. Teamwork is a staple of military mindset that is critical for business at every level that has largely functioned as an independent-centric structure even if teamwork is beneficial and required.

References

Adams, J., Raeside, R., & Khan, H. (2014). Research methods for business and social science students (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications.

Adler, A. B., & Sowden, W. J. (2018). Resilience in the military: The double-edged sword of military culture. Military and Veteran Mental Health, 43–54. Web.

Ahammad, T. (2017). Personnel Management to Human Resource Management (HRM): How HRM Functions? Journal of Modern Accounting and Auditing, 13(9). 412-420.). Human resource management, historical perspectives, evolution and professional development. Journal of Management Development. Web.

Ainspan, N. D., Penk, W., & Kearney, L. K. (2018). Psychosocial approaches to improving the military-to-civilian transition process. Psychological Services, 15(2), 129–134. Web.

Arditi, D., Nayak, S., & Damci, A. (2017). Effect of organizational culture on delay in construction. International Journal of Project Management, 35(2), 136–147. Web.

Barker, H. (2017). Family and business during the industrial revolution (p. 280). Essay, Oxford University Press.

Baskerville, R. F. (2006). The Evolution of Darwinism in Business Studies. SSRN Electronic Journal. Web.

Baumgartner, R. J. (2009). Organizational culture and leadership: Preconditions for the development of a sustainable corporation. Sustainable Development, 17(2), 102–113. Web.

Bejinaru, R. (2018). Assessing students’ entrepreneurial skills needed in the knowledge economy. Management & Marketing. Challenges for the Knowledge Society, 13(3), 1119-1132.

Benmelech, E., & Frydman, C. (2014). Do former soldiers make better CEOs? Kellogg Insight. Web.

Benmelech, E., & Frydman, C. (2015). Military CEOs. Journal of Financial Economics, 117(1), 43-59. Web.

Bismala, L., & Handayani, S. (2017). Improving competitiveness strategy for SMEs through optimization human resources management function. Proceedings of AICS-Social Sciences, 7, 416-424.

Bogoviz, A. V., Ragulina, Y. V., Alekseev, A. N., Anichkin, E. S., & Dobrosotsky, V. I. (2017). Transformation of the role of human in the economic system in the conditions of knowledge economy creation. In International conference on Humans as an Object of Study by Modern Science (pp. 673-680). Springer, Cham.

Breede, H. C. (2019). Culture and the soldier: Identities, values, and norms in military engagements. UBC Press.

Bungay, S. (2012). The art of action: how leaders close the gaps between plans, actions and results.

Burns, W. R. (0AD). Adaptability: Preparing for and Coping with Change in a… Adaptability: Preparing for and Coping with Change in a World of Uncertainty. Web.

Campbell, P. (2019). Military realism: The logic and limits of force and innovation in the US Army. University of Missouri Press.

Caputo, F., Evangelista, F., Perko, I., & Russo, G. (2017). The role of big data in value co-creation for the knowledge economy. ResearchGate. Web.

Castro, C. A. (2018). American military life in the 21st century: Social, cultural, and economic issues and trends. ABC-CLIO.

Cater, J. J., Marketing, D. of M. and, Young, M., Ahlin, Altinay, Bandura, … Young. (2020). US VETERANS AS EMERGING ENTREPRENEURS: SELF-EFFICACY, INTENTIONS AND CHALLENGES. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship. Web.

Charniak, E., & Riesbeck, C. K. (2014). Deductive Information Retrieval: Taylor & Francis Group. Taylor & Francis. Web.

Chemerinsky, E. (2016). Aspen treatise for federal jurisdiction. Wolters Kluwer Law & Business.

Cooper, L., Caddick, N., Godier, L., Cooper, A., & Fossey, M. (2016). Transition from the Military Into Civilian Life. Armed Forces & Society, 44(1), 156–177. Web.

Corbe, M. (2017). A civil-military response to hybrid threats. Springer International Publishing.

Cox, K., Grand-Clement, S., Galai, K., Flint, R., & Hall, A. (2018). Understanding resilience as it affects the transition from the UK Armed Forces to civilian life. RAND Health Quarterly, 8(2). Web.

Deshwal, V., & Ashraf Ali, M. (2020). A Systematic Review of Various Leadership Theories. Shanlax International Journal of Commerce, 8(1), 38–43. Web.

Dexter, J. C. (2020). Human resources challenges of military to civilian employment transitions. Career Development International, 25(5), 481–500. Web.

Felipe, C. M., Roldán, J. L., & Leal-Rodríguez, A. L. (2017). Impact of organizational culture values on organizational agility. Sustainability, 9(12), 2354. Web.

Georgiev, M. (2019). Improvement in the forming of the military professional qualities during the educational process. Knowledge – International Journal, 31(6), 1945-1950.

Gilbert, C., Journé, B., Bieder, C., & Laroche, H. (Eds.). (2018). Safety cultures, safety models: Taking stock and moving forward. Springer International Publishing.

Goodwin, G. F., Blacksmith, N., & Coats, M. R. (2018). The science of teams in the military: Contributions from over 60 years of research. American Psychologist, 73(4), 322-333. Web.

Gregg, M. (2018). Counterproductive: Time management in the knowledge economy. Duke University Press.

Hadad, S. (2017). Knowledge economy: Characteristics and dimensions. Management dynamics in the Knowledge economy, 5(2), 203-225.

Hadid, D. (2021). As allied forces leave Afghanistan, the Taliban keep up its surge. NPR. Web.

Hattangadi, V. (2017). Edgar Schein’s three levels of organizational culture. Web.

Hilden, S., & Tikkamäki, K. (2013). Reflective practice as a fuel for organizational learning. Administrative Sciences, 3(3), 76–95. Web.

Isaacs, K., Mota, N. P., Tsai, J., Harpaz-Rotem, I., Cook, J. M., Kirwin, P. D., Krystal, J. S., Southwick, S. M., & Pietrzak, R. H. (2017). Psychological resilience in US military veterans: A 2-year, nationally representative prospective cohort study.Journal of Psychiatric Research, 84, 301-309. Web.

Johnson, A. P. (2019). Essential learning theories: Applications to authentic teaching situations. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Johnston L.M. (2018). Constructivist theories of leadership. In A. Farazmand (Ed.), Global Encyclopedia of public administration, public policy, and governance (pp. 1100-1103). Springer. Web.

King, N. & Brooks, J. (2017). Thematic analysis in organisational research. In C. Cassell, A. L. Cunliffe & G. Grandy (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative business and management research methods (pp. 219-236). London: Sage.

Kirchner, M., & Akdere, M. (2017). Military leadership development strategies: Implications for training in non-military organizations.Industrial and Commercial Training, 49(7/8), 357-364. Web.

Kiyosaki, R. T. (2015). 8 lessons in military leadership for entrepreneurs. Amazon. Web.

Kolb, R. W. (Ed.). (2018). The SAGE encyclopedia of business ethics and society. SAGE Publications.

Kramer, C. A., & Allen, S. A. (2018). Transformational leadership styles pre-and post-trauma. Journal of Leadership Education, 17(3), 81-97. Web.

Lacerenza, C. N., Marlow, S. L., Tannenbaum, S. I., & Salas, E. (2018). Team development interventions: Evidence-based approaches for improving teamwork. American Psychologist, 73(4), 517–531. Web.

Lyskova, I. (2019, April). Conceptual Basis of the Formation of Organizational Behavior Quality in the Condition of Knowledge Economy. In 3rd International Conference on Culture, Education and Economic Development of Modern Society (ICCESE 2019). Atlantis Press.

MacLean, A. (0AD). Skills Mismatch? Military Service, Combat Occupations, and Civilian Earnings – Alair MacLean, 2017. SAGE Journals. Web.

Matthews, M. D. (2020). Head strong: How psychology is revolutionizing war. Oxford University Press.

Maurer, D. (2017). Crisis, agency, and law in US civil-military relations. Springer International Publishing.

McDermott, M. J., Boyd, T. C., & Weaver, A. (2015). Franchise business ownership: A comparative study on the implications of military experience on franchisee success and satisfaction. Entrepreneurial Executive, 20, 9-30. Web.

McGarry, R., Walklate, S., & Mythen, G. (2014). A Sociological Analysis of Military Resilience. Armed Forces & Society, 41(2), 352–378. Web.

McGinn, D. (2015). What Companies Can Learn from Military Teams. Harvard Business Review. Web.

Megginson, ‘Lessons from Europe for American Business’, Southwestern Social Science Quarterly (1963) 44(1): 3-13, at p. 4.

Nasih, M., Harymawan, I, Putra, F. J., & Qotrunnada, R. (2019). Military experienced board and corporate social responsibility disclosure: An empirical evidence from Indonesia. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 7(1), 553-573. Web.

Nazri, M., & Rudi, M. (2019). Military leadership: A systematic literature review of current research.International Journal of Business and Management, 3(2), 1-15. Web.

Nissinen, V. (2001). Military leadership. A critical constructivist approach to conceptualizing, modeling and measuring military leadership in the Finnish Defense Forces [Thesis]. Web.

Perrewé, P. L., & Harms, P. D. (Eds.). (2018). Occupational stress and well-being in military contexts. Emerald Publishing Limited.

Pianin, E. (2014). The Surprising Reason College Grads Can’t Get a Job. Bentley University. Web.

Pius, A., Alharahsheh, H. H., & Sanyang, S. (2020). Trends and issues in strategic human resources management. In Trends and issues in international planning for businesses (pp. 17-41). IGI Global.

Popkova, E. G. (2019). Preconditions of formation and development of industry 4.0 in the conditions of knowledge economy. In Industry 4.0: Industrial Revolution of the 21st Century (pp. 65-72). Springer, Cham.

Roberts, R. (2018). 12 Principles of modern military leadership: Part 1. 12 Principles of Modern Military Leadership: Part 1. Web.

Ruffa, C. (2018). Military cultures in peace and stability operations: Afghanistan and Lebanon. University of Pennsylvania Press, Incorporated.

Salas, E., Reyes, D. L., & McDaniel, S. H. (2018). The science of teamwork: Progress, reflections, and the road ahead. American Psychologist, 73(4), 593-600. Web.

Samanta, I., & Lamprakis, A. (2018). Modern leadership types and outcomes: The case of Greek public sector. Management: Journal of Contemporary Management Issues, 23(1), 173-191.

Schein, E. H. (2016). Organizational culture and leadership (5th ed.). Wiley.

Stanton, N. A. (Ed.). (2018). Trust in military teams. CRC Press.

Stebnicki, M. A. (2020). Clinical military counseling: Guidelines for practice. Wiley.

Stettner, M. (2019). Capture more details around you by applying military training tools. Investor’s Business Daily. Web.

Storlie, C. (2018). Six must do’s for an effective military to civilian transition. Medium. Web.

Sullivan, G., & Harper, M. V. (1997). Hope is not a method: what business leaders can learn from America’s army. Broadway Books.

Szelągowski, M. (2019). Dynamic Business Process Management in the Knowledge Economy: Creating Value from Intellectual Capital (Vol. 71). Springer.

Szypszak, C. (2016). Military leadership lessons for public service. McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers.

Terziev, V. (2018). Importance of human resources to social development. Proceedings of ADVED.

Vallée‐Tourangeau, F., & March, P. L. (2019). Insight out: Making creativity visible. The Journal of Creative Behavior.

Warrick, D. D. (2017). What leaders need to know about organizational culture. Business Horizons, 60(3), 395-404.

Weber, J. S. (2017). Whatever happened to military good order and discipline? Cleveland State Law Review, 66(1), 123-179.

Wenger, Jeffrey B., et al., Helping soldiers leverage Army knowledge, skills, and abilities in civilian jobs. Rand Corporation, 2017.

Why hire a vet? – shrm. (2017). Web.

Williams, T. A., Gruber, D. A., Sutcliffe, K. M., Shepherd, D. A., & Zhao, E. Y. (2017). Organizational Response to Adversity: Fusing Crisis Management and Resilience Research Streams. Academy of Management Annals, 11(2), 733–769. Web.

Yanchus, N. J., Osatuke, K., Carameli, K. A., Barnes, T., & Ramsel, D. (2018). Assessing workplace perceptions of military veteran compared to nonveteran employees. Journal of Veterans Studies, 3(1), 37-50.

Yildirim, M. C., & Kaya, A. (2019). The contributions of school principals as constructivist leaders to their schools’ organizational change. Asian Journal of Education and Training, 5(1), 1-7. Web.