Background

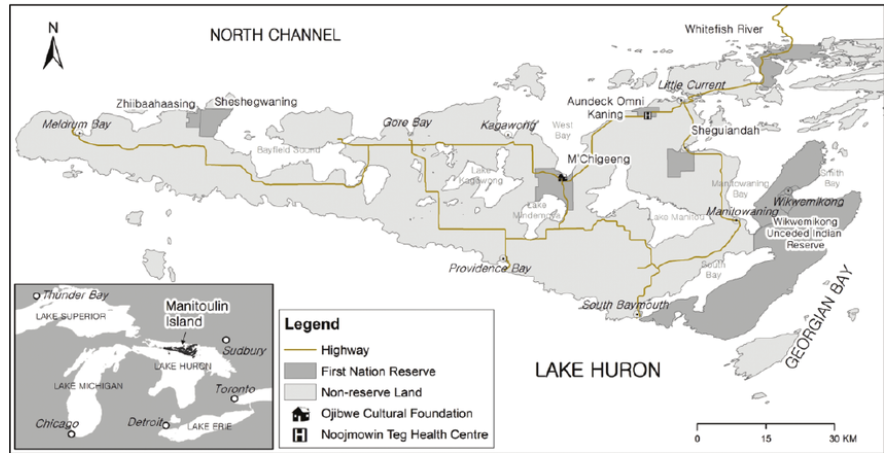

The proposed empowerment project suggests a comprehensive introduction to decolonization for Indigenous and Non-Indigenous residents of Mnidoo Mnising (Manitoulin Island). The introduction should be instated through a food sovereignty project that explores attitudes toward indigenous planting and harvesting in Mnidoo Mnising. Nikolakis and Hotte (2018) claim that “growing recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ legal rights to forests has motivated an increase in collaborative forest governance in recent decades” (p. 46). Decolonizing Indigenous peoples’ cultural, psychological, and economic freedom requires efforts to mobilize communities at the local level. The project will be conducted in the First Nation of M’Chigeeng on Manitoulin Island, northeastern Ontario, Canada.

General Overview and Rationale

Through learning circles with the practice of planting and harvesting, this project will empower Indigenous people to speak to power by exposing the complexity and negativity of patriarchy, colonialism, white supremacy, and capitalism. The issues this projects attempts to solve are: How can Indigenous Feminist protect food sovereignty practices support decolonization? Furthermore: What does decolonization mean to the residents of Mnidoo Mnising (Manitoulin Island)? The weekly multicultural talking circle about food sovereignty changes in the community will provide new tools for decolonization of Indigenous people in five stages. People will be invited to understand the terminology and adopt personal responsibility for the decolonization process of Biskaabiiyang. Greenwood et al. (2018) supply that “geography matters in the lives and being-ness of Indigenous people as more than just human or social construction” (p. 192). Discrimination against the Anishinaabe population is also expected to be discussed in conversational circles. The project’s journey will connect multiple generations and encourage them to have open conversations about resilience and perseverance.

Region Relevance

The struggle for the rights of Indigenous people of the North America region only truly began in the 21th century, and so far, the situation of this population group cannot be called favorable. Indigenous people continue to experience discrimination despite the numerous affirmations from government that it will provide better environment for them. The main problem of colonization is that for most countries, and especially Canada, any national minority looks like a potential source of separatism and social division. Moeke-Pickering et al. (2018), for example, add that “the media plays a large role in facilitating negative racial and gender ideologies about Indigenous women” (p. 54). Thus, decolonization, supported and empowered specifically by Indigenous Feminists, remains a crucial element in the restoration of the Indigenous society.

Location Relevance

Decolonization is a multifaceted process that holds many various aspects to it, from restoration of traditional ways of life to the revival of cultural and literal legacy. This project chose to reinstate the food sovereignty in Mnidoo Mnising, as it will allow the Indigenous population to restore both their economic independence and their traditional way of working with the land. It will also be supported by Indigenous Feminists to empower the local women and uphold their position as preserves of oral cultural legacy. Townsend et al. (2020) add that “many of the high carbon density forests and peatlands that are prioritized for nature-based solutions globally are found within the traditional territories of Indigenous Nations in Canada” (p. 551). Mnidoo Mnising is a fertile land that can provide naturally grown food for the Indigenous community, thus it is extremely important to empower and educate the people of the Anishinaabe tribe on how to work it.

Place Relevance

The core goal of the project is to impart knowledge to young individuals of the local community in order to reclaim sound, voice, identity, and nationhood through learning circles and reconnection to the land. The Anishinaabe should remember how to plant and eat the grown products to ensure fresh food is available to all people in the community. Indigenous feminist analysis and participatory research will also bring women together to discuss Indigenous praxis to mobilize tangible solutions at the grassroots level of food sovereignty decolonization.

Additionally, the community will participate in planting and harvesting activities that will help build and maintain social ties between its members. According to Lines and Jardine (2019), “relationships, interconnectivity, and community are fundamental to the social determinants of Indigenous health” (p. 1). Traditional ways of working with the land will be proposed and discussed as a means of preserving the historical legacy of Indigenous people. Moreover, Indigenous Feminists will be interviewed to gain additional perspective on the matter of food sovereignty. The skills that can be acquired by the Indigenous people in the process of the project can be passed on from generation to generation, which certainly gives greater independence to the people. The accumulations of culture, expressed through the consciousness, will give real benefits to the peoples of Manitoulin for many generations to come.

Movement Relevance

Participation in talking circles, planting and harvesting activities will be open to all Indigenous and non-Indigenous residents of Mnidoo Mnising (Manitoulin Island). People with any occupation and affiliation will be welcome, as it will ensure the multitude of perspectives. The project will require the transfer of necessary seeds to the planting site, which should be discussed with local authorities. Indigenous people should be aware that they are being offered not an exploitative but, on the contrary, a liberating platform for asserting cultural independence. The community will feel more confident about the project if it is promoted and discussed by its actual members instead of being simply advertised through other means such as flyers or posters.

Human-Environmental Interaction Relevance

The project will continue up until there is enough food for the community during the summer months. It will have a significant economic value as it will allow the community to build its food independence and provide sustenance for the vulnerable population. Moreover, it will also hold a social value due to the fact that it will require collective efforts from the members of local society, include cooperative activities, and joint discussions. All this will strengthen social ties between the people, their connection to the land, and ensure their interest in the project’s success. The goal is to have as many sweetgrass gardens growing as possible. It also has feasibility of becoming an important communal way of restoring and preserving local cultural legacy and uniting the people. The project aims at building a complete Indigenous Food Forest Garden. Moreover, any important information regarding the process of working with the land will be shared with the community to ensure the authenticity and efficiency of it.

Budget

The budget should include:

- 2 bags of sweetgrass seeds (3000 seeds and $47 each) – $94;

- 20 packets of elderberry seeds (50 seeds and $5.99 each) – $119.8;

- 10 packets of low-bush wild blueberry seeds (50 seeds and $7.99 each) – $79.9;

- 30 packets of ground cherry seeds (30 seeds and $2.99 each) – $89.7;

- 20 packets of mulberry seeds (50 seeds and $5.99 each) – $119.8;

- 30 shovels ($15 each) – $450;

- 30 hoes ($15 each) – $450;

- Overall budget: $1403.2.

Summary

The project supports the restoration and preservation of local planting and harvesting patterns existing in the community. Additionally, it addresses the issue of economic instability recognized by the local authorities and researchers, as well as helps enrichen and sustain the natural environment. Finally, it has the support of Indigenous Feminist movement as it strives to reinstate the female role in preserving and transferring oral legends, stories, traditions, and other legacy.

References

Barwin, L., Shawande, M., Crighton, E., & Veronis, L. (2015). Methods-in-Place: “Art Voice” as a locally and culturally relevant method to study traditional medicine programs in Manitoulin Island, Ontario, Canada. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 14(5), 160940691561152. Web.

Greenwood, M., Leeuw, S. D., & Lindsay, N. M. (2018). Determinants of Indigenous peoples’ health: Beyond the social. Canadian Scholars.

Lines, L.-A., & Jardine, C. G. (2019). Connection to the land as a youth-identified social determinant of indigenous peoples’ health. BMC Public Health, 19(1). Web.

Moeke-Pickering, T., Cote-Meek, S., & Pegoraro, A. (2018). Understanding the ways missing and murdered Indigenous women are framed and handled by social media users. Media International Australia, 169(1), 54-64. Web.

Nikolakis, W., & Hotte, N. (2019). How law shapes collaborative forest governance: A focus on Indigenous Peoples in Canada and India. Society & Natural Resources, 33(1), 46–64. Web.

Townsend, J., Moola, F., & Craig, M.-K. (2020). Indigenous peoples are critical to the success of nature-based solutions to climate change. FACETS, 5(1), 551–556. Web.