Abstract

The present report utilized secondary research and positivist research philosophy to critically evaluate two Consumer Decision-making Process (CDP) models – the Consumer Decision Model and the Theory of Planned Behavior –, with the aim to bring into the limelight the dark spots of the models when applied to the hospitality industry.

Current literature, though anecdotal in scope and context, has illuminated the fact that many CDP models are vague, inconsistent, and assume an all-encompassing orientation, which constricts their effectiveness and efficacy in explaining post-modernism consumer behavior.

Many of these models have been accused of being largely descriptive in nature and ascribing to a ‘phases-based’ school of thought that is not in sync with today’s consumers and their behavior orientations.

Upon analysis and critique of the sampled models, it has been demonstrated that these models may no longer be tenable in explaining behavior as they view consumers in a rather mechanistic approach and constrict behavior to rationalistic approaches, devoid of any interpretation relating to the consumer as a unique individual who desires to sample unique experiences in the hospitality industry.

The models are vague in their explanation of why consumers must follow the noted phases, and fail to account for external factors that influence consumer behavior in the hospitality industry, such as globalization, hyperreality, and hedonistic consumption patterns.

It is recommended that new paradigms must have the capacity to delineate how consumers find fulfillment through consumption, and how they develop creativity and express their individual capabilities through the consumption of services.

Introduction

The present paper is an attempt to account for perceived vagueness, inconsistencies and all-encompassing orientations of consumer decision-making models by evaluating and critiquing two such models, namely the Consumer Decision Model and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). These models will be evaluated and analyzed within the services context, with particular reference to the hospitality industry.

Despite the broad attention focused on the concept of consumer behavior (Dellaert et al 2012), and in spite of the obvious advantage generated by consumer decision-making models in providing conceptual frames of reference that make it easy to understand different consumer decision processes and marketing paradigms (Erasmus et al 2001), a large portion of these models continue to attract criticism from various quarters due to their perceived vagueness, broad generalizations, and an all-encompassing orientation (Lye et al 2005).

Consequently, the ability for marketers to predict and understand consumer behavior and decision-making is still at a less than desirable level due to the inconsistencies and variances noted in these models.

Consumer Behavior in Hospitality Industry

Belch (1998) cited in Schiffman (2000) defines consumer behavior “…as the behavior that consumers display in searching for, purchasing, using, evaluating and disposing of products and services that they expect will satisfy their needs” (p. 2).

Modern research on consumer behavior no longer derives interest in viewing the consumer as a rational economic being; rather, marketing studies have introduced a range of factors and variables that act either independently or dependently to influence the consumer consumption patterns beyond the mere self-interested act of purchasing as proposed by rational economic theories (Lovelock & Wirtz 2010; Bray n.d.).

To this effect, the hospitality industry must focus on the ‘process nature’ of the service production process (Lovelock & Wirtz 2010), the unique characteristics of services on offer (Tsiotsou & Wirtz 2012), and the impact of these contextual variables on customer behavior (Pachauri 2002).

Extant services literature (e.g., Williams 2006; Miljkovic & Effertz 2010; Oh 1999) demonstrates that marketers in the hospitality industry are still faced with the problem of adopting or developing new paradigms for evaluating customer behavior and decision making, primarily because most of the players in this sector have an imperfect picture of their customer, while only a few have put in place the capacity and capability to monitor patterns of consumer behavior at a degree of detail essential to maintain a competitive edge.

As noted by Bowie & Buttle (2004), many hospitality organizations believe that there are adequately close to their clients due to the co-creation of the service experience.

Consequently, it becomes increasingly important for hospitality organizations to understand the major facets of consumer behavior and decision-making because consumption of services is basically typified as “process consumption”, where the production process is considered to form a fundamental component of service consumption and is not merely perceived as the outcome of a production process, as is the case in the traditional paradigms associated with the marketing of physical goods (Miljkovic & Effertz 2010; Tsiotsou & Wirtz 2012 ).

Postmodern Consumerism within the Hospitality Industry

Today, more than ever, the hospitality industry is increasingly encountering an era that is not guided by any dominant ideological orientation in consumption patterns, but by pluralism of styles (Williams 2002).

This is postmodern consumerism – a trend that is increasingly being reflected in a multiplicity of variables that drive consumer behavior, including advertising and promotions, product and service development, as well as branding (Firal et al 1995).

Available literature demonstrates that postmodern consumerism in the hospitality industry is predominantly initiated by shifts in the social-cultural, psychological and technological domains, which generate new options for experiences and self-expression in consumption (Williams 2002).

This section purposes to briefly describe some the factors that are associated with the new means of consumption, hence new approaches to consumer behavior

Hedonism

The increasing awareness of hedonic consumption among contemporary consumers has not only enhanced pleasure seeking behavior as the only intrinsic good but also luxury consumption to fulfill the variant needs of individuals (Williams 2002).

In the hospitality context, the postmodern consumer is embracing the richness of choice, traditions, and styles to sample products and services that will enable them to achieve the intrinsic good.

As a direct consequence, however, it is increasingly becoming difficult for industry players to predict behavior since consumers are guided by the unconventional urge to experiment on new products and experiences (Firal et al 1995; Thomas 1997).

Fragmentation of Markets & Experiences

The absence of a central ideology to guide postmodern consumption patterns gives rise to a multiplicity of norms, values, beliefs and lifestyles that are adhered to by individuals in the quest for unique products and services.

To satisfy this rising demand for unique experiences, hospitality organizations are increasingly segmenting or fragmenting their product and service offerings (Firal et al 1995), making it increasingly difficult to objectively evaluate consumer behavior and decision making process.

More importantly, the post-modernity orientation is on record for enhancing the production of smaller niche markets in fragmented dispositions, not only making it difficult to successfully evaluate behavior using the current models but also eating into the profitability of hospitality organizations (Van Raaij 1993).

Hyperreality of Products and Services

The hospitality industry is abuzz with hyperreal experiences; that is, experiences that passed as real and authentic but they are, in context and scope, light and empty (Van Raaij 1993). Hyperrealism is largely driven by the insatiable appetite of consumers to enjoy disjointed experiences and moments of excitement, leading industry players to simulate some of the experiences and pass them as authentic and value-added events.

For example, consumers visiting hospitality organizations such as the Disney World and popular theme hotels are made to believe in the physical surroundings, which are mere simulations in the image of hypes (Firal et al 1995).

Globalization

Globalization and convergence of technology have assisted to break down geographical barriers that fueled economic nationalism and chauvinism.

Consumers are no longer consuming products and services based on their ethnic and cultural backgrounds (Van Raaij 1993), though some scholars still maintain consumption patterns are still predetermined by the consumer’s culture, and that globalization has no capacity to standardize consumer behavior (Firal et al 1995; Williams 2002).

More importantly, the intangible nature of services within the hospitality industry necessitates comprehensive individualized marketing and customized services for the customer to experience the unique and superior value.

In this context, it can be argued that the idea of global hospitality organizations to increasingly standardize and customize their products and service offerings is paradoxical in essence based on the fact that these organizations must deal with cultural variations that to a large extent influence consumer’s mind-sets and buying behaviors (Williams 2002).

Brief Overview of Consumer Decision-Making Process

Lye et al (2005) posit that consumer decision-making models are extensively employed in consumer behavior studies not only to structure theory and research but also to comprehend the contextual influences that come into play to influence consumer decision making.

In a comparative assessment of the consumer decision-making process, Engel et al (1995) cited in Erasmus et al (2001) argue that “…a model is nothing more than a replica of the phenomena it is designed to present…It specifies the building blocks (variables) and the ways in which they are interrelated” (p. 83).

Drawing upon this description, these authors argue that models should therefore have the capacity to provide conceptual frames of reference that assist individuals to grasp visually what transpires as variables and circumstances interrelate and shift.

A number of academics, however, punch holes into the existing models of consumer decision-making process due to a multiplicity of weaknesses (Lovelock & Wirtz 2012), which will be illuminated in subsequent sections of this paper, particularly in respect of their incongruent dynamics and operational deficiencies in the hospitality context.

A strand of existing literature (e.g., Schiffman 2000; Lovelock & Wirtz 2010) demonstrates that most paradigms of consumer decision-making presuppose that the consumer’s consumption decision process consists of precise phases through which the customer passes as they interact with the service.

Indeed, a meta-analytic review of marketing literature (e.g., Bowie & Buttle 2004; Lovelock & Wirtz 2010; Pachauri 2002; Miljkovic & Effertz 2010) confirms the most dominant phases a consumer passes through while making purchasing/consumption decisions to include: need identification; information search; appraisal of available alternatives; purchase/consumption decisions, and; post purchase decisions.

Other researchers, however, argue that “…the process of consumer decision-making can be viewed as three distinct but interlocking stages: the input stage, the process stage and the output stage” (Schiffman 2000, p. 14).

But, as acknowledged by Abdallat & El-Emam (n.d.), the overreliance of phases in attempting to explain consumer decision making leads to generalizations of consumer behavior as not every consumer may wish to pass through all these stages when making purchasing/consumption decisions.

Aim & Objectives of the Study

Aim

To critically analyze and critique the two chosen models of Consumer Decision-making Process, namely the Consumer Decision Model and the Theory of Planned Behavior, with the view to determine the extent of their vagueness, inconsistency, and all-encompassing orientation when applied within the hospitality industry.

Objectives

The present paper is guided by the following objectives:

- To critically review extant literature on consumer behavior and decision-making process, particularly with reference to hospitality organizations;

- To identify, justify and critically analyze the two models of Consumer Decision-making Process selected for this study;

- To determine the extent or level of vagueness, inconsistency, and all-encompassing orientation of the two models as they relate to the hospitality industry; and

- To provide some alternatives and recommendations that could be used by industry players to better influence consumer behavior and decision making.

Methodology

Research Philosophy

This report heavily relied on the positivist research philosophy and the deductive approach to critically analyze the selected models of Consumer Decision-making Process for vagueness, inconsistencies and typical all-encompassing orientations, with reference to contemporary hospitality industry.

Positivism entails “…manipulation of reality with variations in only a single independent variable so as to identify regularities in, and to form relationships between, some of the constituent elements of the social world” (Research Methodology n.d., p. 3-1).

Consequently, the researcher evaluated facts from the more general to more specific using the deductive approach with the aim of drawing logical conclusions about the weaknesses of the discussed models from available literature (Burney 2008).

Data Collection

Relevant data and information for this study was collected through secondary research; that is, the researcher engaged in collecting information from third-party sources or information that had been previously collected for some other reason.

Secondary research fits the demands and expectations of this study as it is not only easier and less costly to undertake, but it guides the researcher to effectively answer the research aim and objectives through the use of already existing materials (Thomas 1997).

The research primarily utilized book resources, websites and peer-reviewed articles from a number of subscription databases, including Ebscohost and Emerald, to develop and analyze the relevant themes aimed at providing accurate responses to the research aim and objectives.

Research Limitations

The researcher was constrained by time and budgetary resources to undertake a comprehensive study that could have brought new insights into the important topic of consumer behavior and decision making process.

It is widely believed that a broader engagement with secondary sources and, perhaps, undertaking primary research with hospitality stakeholders, could have resulted in a more comprehensive analysis of the models and more generalizable findings. However, this was not possible due to strict time-lines and budgetary constraints.

Additionally the word limit for the study, which was capped at 4000 words, limited the researchers capacity to expansively detail some of the relevant concepts of consumer behavior and decision making, and compare the sampled models of consumer decision making process with other contemporary models to effectively assess the variations in vague conceptualizations and inconsistent content.

Analysis & Critique

Consumer Decision Model

The Consumer Decision Model, also referred to as the Engel-Blackwell-Miniard Model, was initially developed in 1968 Engel, Kollat, and Blackwell, in their attempt to propose and explain the variables that come into play in informing consumer behavior and facilitating decision making (Erasmus et al 2001).

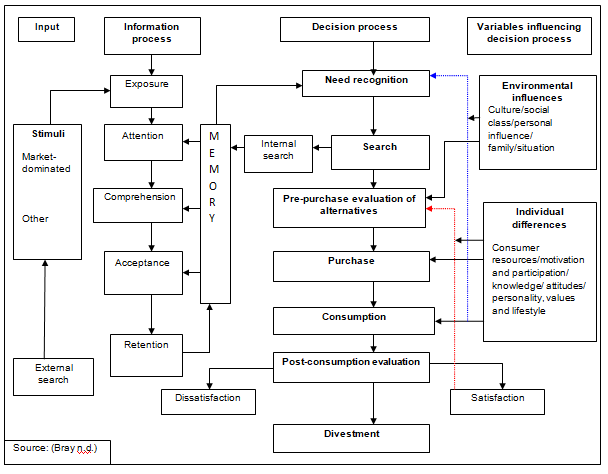

As noted by Bray (n.d.), “… the model is structured around a seven point decision process: need recognition followed by a search of information both internally and externally, the evaluation of alternatives, purchase, post purchase reflection and finally, divestment” (p. 15).

This model further suggests that consumer decisions are influenced by two foremost aspects: “…firstly stimuli is received and processed by the consumer in conjunction with memories of previous experiences, and secondly, external variable in the form of either environmental influences or individual differences” (Bray n.d., p. 15-16).

It is important to note that the environmental factors acknowledged in the model include cultural orientation, social rank, personal influence, family, and situational context, while individual factors include consumer resource/capability, incentive and participation, level of knowledge, values and attitudes, as well as individual traits and lifestyle.

In illuminating the model, it can be argued that entry to the model is through need identification, whereby the consumer actively acknowledges an inconsistency between their present state and some other pleasing choices. The framers of the model assume that the need recognition process is primarily stimulated “…by an interaction between processed stimuli inputs and environmental and individual variables” (Bray n.d., p. 17).

After a specific consumption need has been acknowledged the consumer initializes the search for information, both internally through their deeply-held reminiscences of earlier experiences in hospitality organizations, and externally (Bowie & Buttle 2004).

The model presupposes that the intensity of information search is intrinsically reliant on the scope of problem solving, with novel or intricate consumption problems being subjected to far-reaching external information explorations, while simpler challenges may rely entirely on an unsophisticated internal exploration of prior behavior (Baig & Khan 2010).

Bray (n.d.) notes that information passes through five phases “…of processing before storage and use, namely: exposure, attention, comprehension, acceptance and retention” (p. 17).

The model further posit that the consumer actively evaluates alternative consumption choices using the established set of beliefs, attitudes and consumption intentions (Erasmus et al 2001), with the evaluative process being primarily influenced by both environmental influences and individual influences (Bray n.d). Consequently, the model depicts ‘intention’ as the only precursor to consumption.

While the environmental and individual variables are largely perceived to act on purchase/consumption behavior, Van Tonder (2003) cited in Bray (n.d.) notes that the term ‘situation’ is premeditated as an environmental variable though the factor is also not clearly defined.

However, according to this scholar, the term may imply “…such factors as time pressure or financial limitations which could serve to inhibit the consumer from realizing their purchase intentions” (p. 17).

The other phases entail the actual consumption of the service, followed by post-consumption assessment which grants feedback functionality to the consumer, especially in terms of undertaking future external explorations and belief/value formation (Bray n.d.; Erasmus et al 2002).

When this model is critiqued under the lens of the hospitality industry, it draws its major strength in its potential to evolve ever since the original model was published some four decades ago, to at least encompass some of the variables and challenges facing the contemporary consumer in the hospitality industry (Bowie & Buttle 2004).

For instance, the model has been able to move away from its mechanistic approach of explaining consumer behavior to encompass modern concepts that influence consumer consumption patterns.

Individual variables such as motivation and involvement, as well as environmental variables such as social class, family and situation (Bray n.d.), are better placed to explain how consumers interact with a particular food establishments, and even how such variables may influence return behavior and satisfaction.

However, it is clear that many of these variables remain vague due limited theoretical background (Erasmus et al 2001), with a section of scholars arguing that the model is even unable to specify the exact cause and effect that relate to consumer behavior (Lovelock & Wirtz 2010), while others note that it is too restrictive to sufficiently accommodate the variety of consumer decision situations in a hospitality environment characterized by shifting consumption patterns and ever increasing competitive pressures (Tsiotsou & Wirtz 2012; Oh 1999).

Foxal (1990) cited in Bray (n.d.) argues that the Consumer Decision Model avails a clear illustration of the consumption process, making it easy for marketers to internalize its dynamics to influence purchase behavior.

The present paper challenges this perspective as consecutive research studies (e.g. Cave 2002; Kotler et al 1999; Bowie & Buttle 2004) demonstrate that consumers, particularly in the hospitality industry, often engage in non-conscious behaviors that may not be modeled through a rational decision making paradigm.

For example, the consumer may purchase a plate of food in an up market hotel, not because they engaged in pre-purchase evaluation of available alternatives to the hotel but due the fact that the servicescape of the facility blurred their conscious decision-making processes.

Upon testing the Consumer Decision Model, Rau & Samiee (1981) were of the opinion that the model is extraordinary in scope and range, but its factual vigor in explaining and justifying consumer behavior “…has been significantly obscured by the fact that most research efforts so far have only been directed toward specific segments of the model rather than at the model as a whole” (p. 300).

In light of these assertions, it can only be argued that this model is not only inherently weak to be of much assistance to the service marketing practitioner but it lacks specificity and thus is difficult, if not impossible, to study and operationalize in hospitality settings.

According to Bray (n.d.), the environmental and individual influences of Consumer Decision Model continue to draw “…criticism due to the vagueness of their definition and role within the decision process” (p.).

For example, while the model clearly identifies and delineates environmental influences such as social class and family, it fails to explain the role of such influences in affecting behavior, giving room to vague generalizations. In the hospitality industry, it becomes even difficult to follow the direction of the influences as the model suggests since some variables are not diametrically ordered as is the case in the goods industry.

Although the model suggests that the consumer has the capacity to decipher some experience attributes before purchasing a product (Erasmus et al 2002), it is increasingly difficult to validate such an assertion in the hospitality industry because most of the experience attributes cannot be evaluated before the actual consumption of the service (Lovelock & Wirtz 2010).

What’s more, experience attributes and individual motives for consumption in the hospitality industry relates more to issues of emotions and the role of heuristics in determining behavior. However, these issues are not adequately covered in the Consumer Decision Model as it only limits the role of individual motives to the process of need recognition (Erasmus et al 2002; Bray n.d.).

Lastly, a widespread concern of the ‘analytic’ approaches such as the Consumer Decision Model regards the unobservable nature and scope of the many variables under consideration (Baig & Khan 2010).

Consequently, it may still be difficult to ascertain whether this particular model provides a precise representation of consumer behavior during consumption (Bowie & Buttle 2004), and whether it has any predictive value in hospitality settings (Williams 2006).

Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

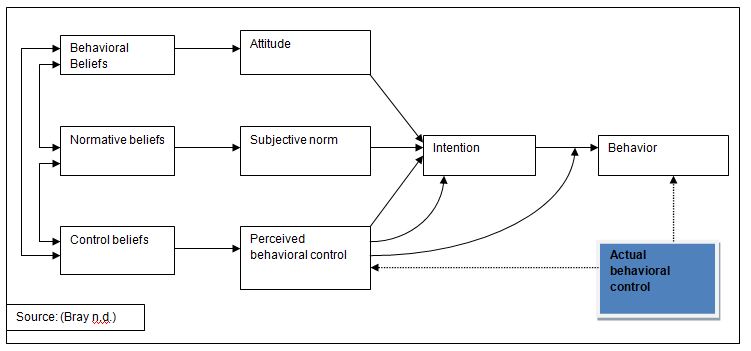

The Theory of Planned Behavior (illustrated in Appendix 2) is an offshoot of the Prescriptive Cognitive Models that were first developed in the 1960s by researchers such as Fishbein and Bertram, who sought to primarily focus on beliefs and attitudes as principal determinants of consumer behavior and decision-making (Bowie & Buttle 2004).

The famous Fishbein model, for example, proposed that the consumer’s “…overall attitude toward an object is derived from his beliefs and feelings about various attributes of the object” (Bray n.d., p. 20). The TPB simply extends this perspective as it seeks to address the perceived overreliance on intentions (from rationalistic models) to predict consumer behavior (Rau & Samiee 1981).

From the illustration in Appendix 2, it is important to note that “…the construct perceived behavior control is formed by combining the perceived presence of factors that may facilitate or impede the performance of a behavior and the perceived power of each of these factors” (Bray n.d., p. 22).

Actual behavioral control, which in normal cases is far challenging to accurately appraise, refers to the degree to which the individual has the expertise, assets, know-how, and other fundamentals required to exhibit a given behavior (Cave 2002). Perceived behavioral control, which functions as a substitute measure of the influence, is assessed and quantified through uniquely designed data collection instruments.

The TPB also asserts that consumer behavioral intention is controlled by a forceful range of variables, including the consumer’s attitude and values, their prejudiced norms and beliefs, as well as their perceived behavioral control influences (Thompson et al 2009).

As such, it can be argued that actual consumer behavior as explained by the TPB is derived largely from behavioral intention, but is controlled and mediated to some extent by perceived behavioral control mechanisms (Bowie & Buttle 2004).

The TPB, which has over the years evolved to become the dominant expectancy-value theory (Bray n.d.), has its own strengths and weaknesses when applied within the context of the hospitality industry. For example, it is a well known fact that many consumers form a perception of a particular restaurant or bar based on their beliefs and attitudes rather than intention.

Consequently, it can be argued that this framework has the capacity to capture a substantial proportion of variance in the consumer’s decision to consume a particular service rather than over relying on the ‘intention attributes’ popularized by rationalistic models.

Additionally, the theory not only avails predictive validity for its application in a varied range of hospitality scenarios as a direct consequence of its ability to convey subjective variables that influence the consumer’s consumption patterns (Cave 2002; Reid & Bojanic 1988), but it is effective in providing prudential justification of the informational and motivational influences on consumer behavior.

Lastly, on strengths, it can be argued that the TPB forms one of the easiest theories to understand and operationalize in hospitality settings.

The TPB has been accused of projecting a vague orientation as it relies on the researcher’s ability to precisely recognize and enumerate all prominent attributes that are considered by the consumer in forming their belief and attitude (Rau & Samiee 1981; Neely et al 2010).

Such an accurate identification and measurement of prominent consumer attributes is clearly impossible in the hospitality industry as the consumer is influenced by a multiplicity of both conscious and sub-conscious variables in considering what choice of food to order (Kotler et al 1999), or what choice of holiday experience to consider.

Consequently, it can be argued that employing such a theory to evaluate consumer decision-making process in the hospitality industry borders on the optimistic.

The TPB also relies on the presupposition that the consumer commences comprehensive cognitive processing before making a purchase (Dallaert et al 2012; Macinnis & Folkes 2010).

This presupposition does not hold much water in the hospitality industry as experience demonstrates that most consumers make spontaneous and emotional decisions in deciding where to go for lunch, or in deciding which hotel facility offers the best services. Consequently, “…the reliance on cognition appears to neglect any influence that could result from emotion, spontaneity, habit or as a result of cravings” (Bray n.d., p.24).

It is indeed true that most consumers visiting hotels and restaurants for food and drinks for the behavior not necessarily from attitude evaluation as proposed in the theory, but from an overall affective response that is especially related to the facility, food or drink of choice.

Conclusion & Recommendations

From this evaluation and critique, it is indeed clear that marketing professionals in hospitality organizations can no longer continue to employ insufficient marketing paradigms, such as the Consumer Decision Model and the theory of Planned Behavior, in their attempt to understand consumer behavior and decision making.

Rather, they need to refocus their energies on evolving these theories and models to portray consumers as emotional beings, focused on achieving pleasurable experiences, creating identities, and developing a sense of belonging through consumption (Williams 2006).

The new paradigms, it is widely believed, must also have the capacity to delineate how consumers find fulfillment through consumption, and how they develop creativity and express their individual capabilities through the consumption of services.

Reference List

Abdallat, M.M.A & El-Emam, H.E, Consumer behavior models in tourism. Web.

Baig, E & Khan, S 2010. ‘Emotional satisfaction and brand loyalty in hospitality industry’, International Bulletin of Business Administration, vol. 11 no. 7, pp. 62-66.

Bowie, D & Buttle, F 2004, Hospitality marketing, Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford.

Bray, J, Consumer behavior theory: Approaches and models. Web.

Burney, S.M.A 2008, Inductive & deductive research approach. Web.

Cave, S 2002, Consumer behavior in a week, Hodder & Stoughton, London.

Dellaert, Benedict G.C & Haubl, G 2012, ‘Searching in search mode: Consumer decision processes in product search with recommendations’, Journal of Marketing Research, vol. 49 no. 2, pp. 277-288.

Erasmus, A.C, Boshof, E & Roesseau, G.G 2001, ‘Consumer decision-making models within the discipline of consumer science: A critical approach’, Journal of Family Ecology and Consumer Sciences, vol. 29 no. 3, pp. 82-90.

Firal, A.F, Dholakia, N & Vankatesh, A 1995, ‘Marketing in a postmodern world’, European Journal of Marketing, vol. 29 no. 1, pp. 40-56.

Kotler, P, Bown, J & Markens, J 1999, Marketing for hospitality and tourism, 2nd Ed, Prentice Hall, London.

Lovelock, C & Wirtz, J 2010, Services marketing, 7th Ed, Prentice Hall, London.

Lye, A, Shao, W, Rundle-Thiele, S & Fausnaugh, C 2005, ‘Decision waves: Consumer decisions in today’s complex world’, European Journal of Marketing, vol. 39 no. 1, pp. 216-230.

Macinnis, D.J & Folkes, V.S 2010, ‘The disciplinary status of consumer behavior: A sociology of science perspective on key controversies’, Journal of Consumer Research, vol. 36 no. 6, pp. 899-914.

Miljkovic, D & Effertz, C 2010, ‘Consumer behavior in food consumption: Reference process approach’, British Food Journal, vol. 112 no. 1, pp. 32-43.

Neely, C.R, Min, K.S & Kennett-Hensel, P.A 2010, ‘Contingent consumer decision making in the wine industry: The role of hedonic orientation’, Journal of Consumer Marketing, vol. 27 no. 4, pp. 324-335.

Oh, H 1999, ‘Service quality, customer satisfaction, and customer value: A holistic perspective’, Hospitality Management, vol. 18 no. 2, pp. 67-82.

Pachauri, M 2002, ‘Consumer behavior: A literature review’, The Marketing Review, vol. 2 no. 1, pp. 319-335.

Rau, P & Samiee, S 1981, ‘Models of consumer behavior: The state of the art’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, vol. 9 no. 3, pp. 300-316.

Reid, R.D & Bojanic, D.C 1988, ‘Hospitality marketing management, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ.

Research Methodology. Web.

Schiffman, L.G 2000, Consumer behavior, Pearson Education Australia, Belmont, WA.

Thomas, M.J 1997, ‘Consumer market research: Does it have validity/some postmodern thoughts’, Marketing Intelligence & Planning, vol. 15 no. 2, pp. 54-59.

Thompson, D.V, Hamilton, R.W & Petrova, P.K 2009, ‘When mental simulation hinders behavior: The effects of process-oriented thinking on decision difficulty and performance’, Journal of Consumer Research, vol. 36 no. 4, pp. 562-574.

Tsiotsou, R.H & Wirtz, J 2012, “Consumer behavior in service context”, In V. Wells & G. Foxall (eds), Handbook of Developments in Consumer Behavior, Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd, Northampton, MA, pp. 147-201.

Van Raaij, W.F 1993, ‘Postmodern consumption’, Journal of Economic Psychology, vol. 14 no. 3, pp. 541-563.

Williams, A 2002, Understanding the hospitality consumer, Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford.

Williams, A 2006, ‘Tourism and hospitality marketing: Fantasy, feeling and fun’, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, vol. 18 no. 6, pp. 482-495.

Appendix