Introduction

The UK has three distinctive legal authorities. They comprise of Scotland, Northern Ireland, and England and Wales. Even though there are refined variances among the three sovereign judicial structures, it should be noted that they share considerable parts of the common law (Riches 67 par.5).

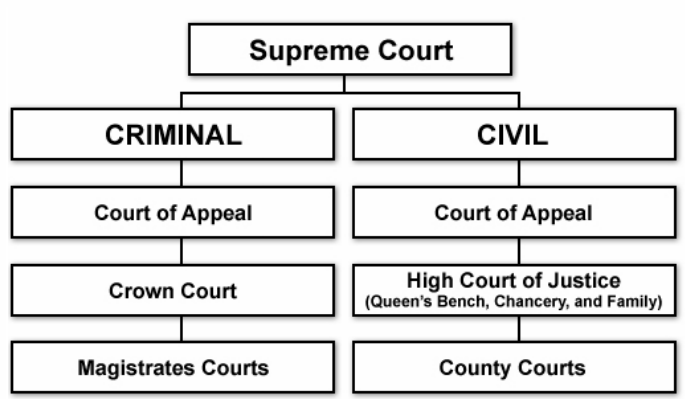

The article below illustrates the hierarchical arrangement of the court structure in England and Wales. Through this, an examination of each of the principal law courts will be provided with a stress on civil courts. Similarly, the article seeks to emphasis on how the common law policy of binding precedent relates to the court system.

The hierarchical arrangement of the court structures in England and Wales

In the United Kingdom, new laws are generated by the parliament or common law using judicial rulings (Adams 54 par.4). Parliament comprises of the House of Lords. The Parliament is mandated to legislate various statutes, which generate new laws. The hierarchal arrangement of the court system in England and Wales dictates that lower courts ought to put up with the higher court’s ruling.

The table below illustrates the hierarchical arrangement of the court structure in England and Wales. The legal structure is indicated in descending order, which implies beginning with the highest-level court of the pecking order and concluding with the lowest one.

Supreme Court

In England and Wales, the Supreme Court is the utmost court of petition. It is the topmost court in the hierarchical judicial system (Adams 55 par.2). Prior the passage of the Constitutional Reform Act 2005, the House of Lords oversaw the above responsibility (Arnold 443 par.8). The court is also the uppermost court of appeal for decentralization issues. It hears petitions from the Court of Appeal and at times from the High Court.

Senior Courts of the England and Wales

They are second in hierarchy. They came into existence after the passage of Judicature Acts. They were later called the Supreme Court of England and Wales in early 1980 (Bass 12 par.4) However, with the enactment of the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 the courts obtained their present name. They comprise of the following courts:

- Court of Appeal – it comprises of two partitions. They are Civil Division and Criminal Division. The Civil Division adjudicates to cases from High Court, County Courts, and other higher court of law. On the other hand, Criminal Division adjudicates to cases from Crown Court linked with hearings of severe offenses.

- High Court – it operates as a public court of first appeal and a civic and criminal appellate law court dealing with issues from lesser courts. It comprises of three segments. They are the Queen’s Bench, the Chancery, and the Family partitions. The segments of this court are not discrete courts. As such, the divisions have slightly distinct processes and practices modified for their roles. Even though specific kinds of trials will be allocated to each partition based on their cases, every detachment may use the authority of the High Court. Nonetheless, initiating proceedings in the incorrect segment may lead to a cost punishment.

- Crown Court – this court adjudicates to issues for appellate and original authority. In England and Wales, this is the only court with powers to hear issues on an indictment. When adjudicating such a responsibility, it is the highest court. As such, the Clerical Court of the Queen’s Bench Division of the High Court does not have jurisdictions to review its verdicts.

Subordinate Courts

They are the third courts in hierarchy (Hazell 47 par.3). In England and Wales, Subordinate Courts are made up of the following courts:

- Magistrates’ Courts- in these courts, a lay magistrate’s bench, or a regional magistrate oversees hearings. No judges are present in these courts. They adjudicate petty criminal cases and some licensing pleas.

- Family Proceedings Courts – these courts arbitrate over domestic issues such as care cases. They also have the power to give adoption commands (James 53 par. 4). As such, these courts are not accessible to the public.

- Youth Courts – these courts arbitrate over cases involving criminals aged between ten and seventeen years. A set of skilled adult justices oversees these courts.

- County Courts – the courts are homegrown courts with only civil authority. They are present in 92 metropolises and municipalities of England and Wales. A district judge oversees them.

Special Courts

Additional exceptional courts in England and Wales are indicated below.

- Coroner’s Court – it handles with the issues of demise in doubtful circumstances.

- Ecclesiastical courts – is a unique court that addresses issues concerning the material goods of the Church of England.

Other Courts

The supplementary courts in England and Wales are indicated below:

- Military Courts – overseen by military personnel in problems linked to court martial.

- Election Courts – addresses pleas against the outcomes of the election.

- Patents County Court – hears cases involving some unpretentious intellectual assets.

The common law and the doctrine of binding precedent

Common law

From the 12th century, English law has been referred as a common law instead of civil law (Riches 97 par.5). The above imply that the law has not been collected or restated with respect to its legal codes. Therefore, its judicial precedents are obligatory. During the prime periods of English common law, justices and adjudicators were accountable for adjusting the system of injunctions to satisfy everyday requirements. Through this, they used a combination of precedent and common sense to create up a structure of internally reliable law.

In England and Wales, adjudicators through judgments of courts and related hearings that resolve discrete cases produce the common law. Common laws are opposed to statutes, which are approved through the parliamentary procedure or protocols dispensed by the executive branch. A “common law system” is an authorized structure, which offers a great importance on common law (Riches 157 par.9). The above protocol dictates that dependable doctrines applied to analogous evidence should yield comparable results. The frame of earlier common law obligates judges who come up with future verdicts, in the same way any other law does, to safeguard consistent treatment.

Precedent

The concept of binding precedent is fundamental in the court structure in England and Wales. The principle refers to the fact that in the hierarchical assembly of courts in England and Wales, a verdict of a higher court is binding on a lesser court (James 56 par. 9). When adjudicators adjudicate issues, they will investigate if a comparable condition has earlier come before a court.

If the precedent was established by a court of equivalent or greater rank to the court hearing the new case, then the arbiter in the current case is expected to abide by the rule of law set in the previous case. It is imperative to establish that it is not the actual pronouncement in a hearing that establishes the precedent. As such, the precedent is established by the rule of law on which the verdict is based. The law, which is a concept from the truths of the case, is identified as the ratio decidendi of the litigation.

Any declaration of law, which is not an important portion of the ratio decidendi is redundant. Such announcement is called obiter dictum. Even though obiter dicta declarations do not constitute to binding precedent, they act as persuasive power and may be considered in future cases.

In instances where disagreements emerge with respect to whether the law is a common law, the courts are required to review previous precedential verdicts of pertinent courts. If a comparable issue has been decided in preceding cases, the court is typically bound to abide by the rule utilized in the previous decision.

When the court establishes that the present disagreement is fundamentally different from all earlier cases, adjudicators have the power and responsibility to establish a law by creating a precedent. The fresh judgment will be a precedent and will obligate upcoming courts.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it should be noted that the hierarchal arrangement of the court system in England and Wales dictates that lower courts ought to put up with the higher court ruling. In England and Wales, the Supreme Court is the utmost court of petition. It is the topmost court in the hierarchical judicial system. Subordinate to the Court of Appeal are Senior Courts, and Subordinate Courts.

In England and Wales, adjudicators through judgments of courts and related hearings that resolve discrete cases produce the common law. The concept of binding precedent is fundamental in the court structure. The principle refers to the fact that in the hierarchical assembly of courts in England and Wales, a verdict of a higher court is binding on a lesser court.

Works Cited

Adams, Alix. Law For Business Students. Harlow, England: Pearson Longman, 2008. Print.

Arnold, William. “The Supreme Court of the United Kingdom: Something Old and Something New”’. Commonwealth Law Bulletin 36.3 (2010): 443-451. Print.

Bass, Cowman. “Anaesthetist’s Guide To The Coroner’s Court In England And Wales”. BJA Education (2015): 12-13. Print.

Hazell, Robert. “Supreme Court UK-Style’. Amicus Curie 2.4 (2011): 47-48. Print.

James, Adrian. “Children, the Uncrc, And Family Law In England And Wales”. Family Court Review 46.1 (2007): 53-64. Print.

Riches, Sarah. Keenan And Riches’ Business Law. Harlow, England: Pearson Education UK, 2013. Print.