Introduction

Background

The staggering economic growth witnessed in China has increased the median income of the average citizen and had an unintended consequence of increasing the demand for higher education (Zhang & Fagan 2016). The rise in wealth and the increase in demand for high-quality education mean that there is a strong need to bridge students’ needs with currently available education services not only within China but around the world as well (Perez-Encinas & Rodriguez-Pomeda 2018).

However, students in China have experienced problems seeking the right partners who understand their personal and educational needs. The language barrier that exists between prospective Chinese students and most western universities has compounded this problem.

According to Huang, Wang and Li (2015), China is among the leading sources of international students for many western universities. Relative to this view, it is estimated that up to 500,000 Chinese students leave the country in search of better educational opportunities in western countries (SML 2019). Therefore, it is not a surprise that China is an attractive market for setting up a recruitment agency to facilitate student travel and provide educational resources for pursuing international education (SML 2019).

Furthermore, there is competition from many recruitment agencies that are increasingly targeting Chinese students to study abroad because of the strategic importance of China as a source of international students (Perez-Encinas & Rodriguez-Pomeda 2018). Nonetheless, most of these foreign international recruitment agencies have failed to make a significant impact on the Chinese economy because of language barriers or poor strategic choices (Perez-Encinas & Rodriguez-Pomeda 2018).

Most international students in China encounter difficulties choosing their preferred majors and identifying the best universities to study (Zhang & Fagan 2016). Notably, most of them who leave their high schools and have aspirations of seeking higher education internationally have little or no understanding of the global education system or variations of it (Chankseliani 2018). Consequently, there is a need to educate them about best practices and inform them about available educational opportunities that would enable them to achieve their personal and career goals.

The main goal of students to seek higher education (internationally) is to give them access to all materials and knowledge available, subject to their respective fields of study (Özoğlu, Gür & Coşkun 2015). Educational agencies serve the purpose of linking students with universities that would help them to achieve their personal and career goals (Perez-Encinas & Rodriguez-Pomeda 2018). Therefore, educational agencies play an important role in reducing the stress associated with selecting and gaining admission to higher institutions of education (Perez-Encinas & Rodriguez-Pomeda 2018).

According to Popkewitz, Feng and Zheng (2018), a good educational agency should offer students with a wide variety of placement options to allow them to select one that suits their educational needs and budget. This view means that reputable agencies work with a variety of educational institutions to identify the best fit for their students’ needs (Perez-Encinas & Rodriguez-Pomeda 2018). However, the selection process is premised on the ability of a student to explain their needs for an agency to provide the best match. This background informs the need to set up an educational agency to help Chinese students get the best placement in international universities. The aim of the proposed study is highlighted below.

Aim

To set up an educational agency to recruit international students in China

Objectives

- To assess the practicality of setting up an educational agency to recruit international students in China.

- To identify the tools and resources necessary to set up an educational agency for international students in China.

- To identify all relevant stakeholders needed to set up an education agency for international students in China.

- To assess the opportunities available for setting up an education agency for recruiting Chinese students to study abroad.

Literature Review

This section of the proposal highlights what other researchers have said about the research topic. A synopsis of the findings will be explored through an assessment of three key research areas: international students’ needs in higher education, assessment of the existing educational agencies in China and challenges in international student recruitment.

Challenges in International Student Recruitment

Recent changes in visa and travel regulations have made it difficult for international students to get admission in different universities around the world (Rasmussen et al. 2015). The hesitation of some parents to allow their children to study in certain parents of the world, coupled with the attempt by authorities to stop accredited institutions from recruiting international students through agencies, have further compounded the problem (Rasmussen et al. 2015).

These restrictions are emerging at a time when most western-based institutions of higher education are looking to increase the enrolment numbers of international students in their jurisdictions (Perez-Encinas & Rodriguez-Pomeda 2018).

The use of agents to recruit international students in many accredited institutions has elicited a lot of controversies because the term “agent” evokes misunderstanding among stakeholders who question their role in recruiting students (Özoğlu, Gür & Coşkun 2015). This problem has been witnessed in different jurisdictions around the world, such as the United States, where agents have experienced challenges in creating a reliable channel for education institutions to admit international students (Chankseliani 2018).

This problem stems from the suspicion surrounding agency roles in international student recruitment because some universities are concerned about the legality of the process and the possibility of these institutions “double-dipping” financially by charging students for services offered and taking a commission from the concerned universities as well (Zhang & Fagan 2016). However, these concerns have not deterred students from seeking the services of recruitment agencies because they are aware of the additional services offered by them.

Assessment of the Existing Educational Agencies in China

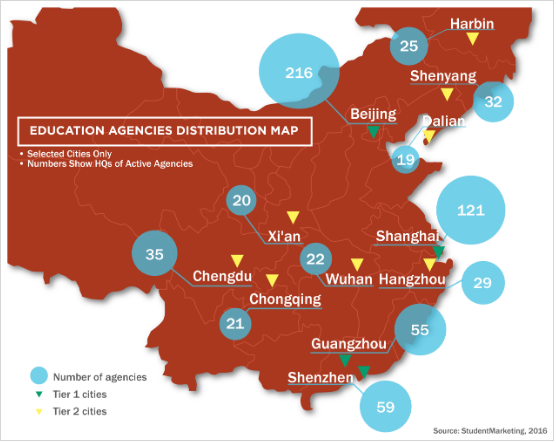

According to the China Higher Education (2019), there are about 450 education recruitment agencies in China. Figure 1 below shows that most of them are located in major cities (tier 1 cities), while smaller metropolitan areas have fewer agencies.

Studies also suggest there are about 10,000 agents who work officially or unofficially as recruiters in China (China Higher Education 2019). This statistic marks an increase in the population of recruiters because their numbers have increased commensurately with the demand for higher education among Chinese students locally and internationally. Firms that have been in the market for a long time have mature recruitment channels, which make it expensive for the average student to seek their services.

Alternatively, large recruitment agencies command a significant portion of the market because it is estimated that the top three recruitment firms in China control about 30% of the market (China Higher Education 2019). Furthermore, several smaller recruitment agencies, which have a significant impact on the market are poorly reported in mainstream studies. However, their impact can be felt in different cities and regions around China (China Higher Education 2019).

Different universities around the world have adopted unique methodologies for working with recruitment agencies in China. Multiple variables affect the relationship between these agencies and the participating institutions. One of them is the geographical location of the impact that the recruiters have (Rasmussen et al. 2015). For example, education agencies tend to work with universities or colleges that are close to their areas of operation. The number of agencies engaged could also influence the relationship between recruiting agencies and partner organisations because the fewer the number of agencies, the more engaged the universities become. The size of the agencies involved and their license status also influence how well they collaborate with reputable institutions of higher learning (Zhang & Fagan 2016).

Lastly, although complex research and market intelligence are needed to select the best type of agency, little market research has been done to fully understand the background of these recruitment agencies. Some key performance indicators that have been used to assess their performance include location, portfolio, area of expertise, destination focus, size and productivity (among others) (Hyams-Ssekasi, Mushibwe & Caldwell 2014; Hodge, Salloum & Benko 2016).

International Students’ Needs in Higher Education

The needs of international students in higher education largely influence the services they get from recruitment agencies. Indeed, it is the role of international students to match student’s needs with the educational services offered in institutions of higher education (Green 2019). Three studies authored by Schatz (2016) Shaheen (2016), Gale and Parker (2017) investigated the perceptions of student’s needs in Australia, Canada, Finland and the UK.

They suggested that these countries have unique educational environments that affect the enrolment of international students. They hold the view that the US is the leader in providing high-quality education among the groups of countries identified above, while Canada is deemed to have the most affordable institutions of higher learning (Schatz 2016; Shaheen 2016; Gale & Parker 2017).

Summary

The need for a recruitment agency cannot be ignored when looking for international placement in higher education because students often spend up to two years to decide which country or institution to study. Agents play an important role in improving the number of Chinese students studying internationally because they help them to navigate language barriers, visa requirements and even the interview process.

Broadly, this literature review has highlighted the importance of analysing the motivation and capabilities of international recruitment agencies when reviewing their efficacy in matching students’ needs with existing educational requirements. However, there is a need to understand whether the establishment of another recruitment agency could further remedy this need by reaching underserved populations.

Methodology

Research Approach

The mixed methods research approach will provide the overriding research framework for the proposed study. It is comprised of a combination of the qualitative and quantitative research approaches (Uprichard & Dawney 2019; Clark-Gordon, Workman & Linvill 2017). The justification for using this approach is to allow for complete and synergistic use of data. Therefore, if either qualitative of quantitative approaches were used separately, such synergy will be lost as the data would be developed separately (Dewasiri, Weerakoon & Azeez 2018).

The mixed methods research approach stems from the social sciences and researchers have widely adopted it in many fields of study. Relative to this assertion, Moseholm and Fetters (2017) suggest that a well-designed mixed methods framework should collect and analyse both qualitative and quantitative data, use rigorous data collection techniques, integrate data effectively and use procedures that implement both qualitative and quantitative approaches concurrently or sequentially.

Research Design

According to Research Rundown (2016), six research designs are linked with the mixed methods research approach. They include sequential explanatory, sequential exploratory, sequential transformative, concurrent triangulation, concurrent nested and concurrent transformative techniques (Research Rundown 2016). The sequential transformative method will be used in this study because there will be no preference for the collection of either qualitative or quantitative data because the investigation is exploratory. Collectively, the results of the qualitative and quantitative phases will be integrated into the data analysis phase.

The main justification for proposing to use this technique is its ability to employ methods that best serve a theoretical purpose. Therefore, it is possible to use the design to fit the purpose of this investigation, which is to set up an educational agency to recruit international students in China.

Data Collection Method

The pieces of information that will be used to address the research issues will be collected from secondary resources. Notably, data will be gathered from industry reports, government publications, books and journals. Books and journals would be obtained from reputable and scholarly databases, such as Google Scholar and Sage Journals. Alternatively, industry reports will be obtained from credible websites, such as corporate and government websites. An effort will be made to only include updated information published within the last five years to make sure the data obtained is relevant to the period under investigation. Similarly, the researcher will seek data from peer-reviewed journals because the information obtained in these reports has been scrutinised by other experts.

These above-mentioned procedures for data collection will be observed to safeguard the quality of information gathered in the data collection process. For example, company websites and government publications have a higher credibility of findings compared to blogs or media publications (Garner, Wagner & Kawulich 2016; Björk et al. 2017). Therefore, there will be a deliberate effort to avoid commercial websites and other unreliable online resources when obtaining data. Such data collection procedures will be observed to safeguard the quality of information obtained in the study and improve the accuracy of data collected.

Broadly, secondary research will be used in the study because it is a cost-effective way of collecting data (Morgan 2019). Furthermore, it offers a timely way of gathering important pieces of information because the materials are freely accessible. Secondary research data is proposed as the main mode of data collection because it gives the researcher access to extensive data relating to the research objectives.

This approach to data collection is also appropriate for this study because it has a wide scope of focus, which is supported by the review of different issues relating to setting up an educational recruitment agency in China, which are mentioned in the research objectives. To recap, the objectives of the study focus on identifying key stakeholders, resources, opportunities available and practicalities of setting up an educational agency in China. These different aspects of analytical review demand a wide scope of analysis for addressing the research topic. Secondary research provides this wide focus.

One of the limitations of using published articles as the main form of data collection is the indicative nature of their findings (Farrell, Tseloni & Tilley 2016). In other words, the information gathered from this process may lack specificity in applicability because data is obtained from a wide spectrum of sources, which may not necessarily be directly related to the research topic under investigation.

However, to overcome this challenge, the data collection process will be focused on obtaining Chinese-based information. This approach to data collection will make sure that the information obtained for review is primarily focused on the Chinese market. Alternatively, data related to other countries will be included in the analysis for comparison purposes. Lastly, the use of secondary research data as the main mode of data collection means that there will be no need for addressing sampling requirements because no human subjects will be involved in the study.

Data Analysis Method

As highlighted above, the data collection process will be focused on the review of published information. Data will be assessed using the thematic method, which involves the process of identifying core themes from the articles reviewed and relating them to key research objectives (Kuckartz 2014; Willig & Rogers 2017). The steps linked to this data analysis technique will be categorised into six key stages: familiarising the researcher with the data, assigning preliminary codes to describe the content, searching for patterns or themes from the codes, reviewing the themes, defining and naming them and producing the final report (Smith & Sparkes 2016).

Ethical Issues, Reliability and Validity of Findings

Studies by Dalessandro (2018), Fetters and Molina-Azorin (2019) suggest that the main ethical issues affecting studies that use secondary data have remained the same for many years. However, unlike primary research studies, which often use human subjects for data collection, the growing relevance of technology in gaining access to research resources in secondary research has created a need to understand issues relating to data sharing, compilation and storage (Ellard-Gray et al. 2015).

To address these problems, information that will be obtained from the research process will be stored in a computer and analysed for consistencies. The goal will be to make sure that the data obtained is credible and consistent with the objectives of the study. Research articles that require special permission to gain access to data will be excluded from the analysis but those that are freely accessible will be used and cited accordingly or acknowledgements to the authors made. Any identifying information related to the materials will also be protected in the final report because the data will be presented anonymously. Broadly, the ethical considerations for the proposed study will be fulfilled as per the university’s ethical requirements.

Lastly, there is a need to assess the reliability and validity of the findings obtained because the secondary research materials that will be reviewed were not primarily designed to address the current research issue. Therefore, the methodology used to come up with their findings will be examined for accuracy, reliability and validity by reviewing different assessment indicators, such as the period taken to collect data and the purpose for doing so.

Conclusion

Overall, this research proposal has highlighted the importance of recruitment agencies in matching student needs with available education opportunities in the UK and other international markets. The findings of this study will be instrumental in meeting the growing demand for higher education in China, particularly among underserved populations. Data will be collected using secondary research and emphasis will be made to obtain updated information published within the past five years.

Subsequently, the data gathered will be analysed using the thematic method. The project is expected to span across four weeks and the findings presented to the university after the lapse of this time. Key recommendations are expected to guide the researcher in bridging the gap between the educational needs of students in China and available opportunities in the UK.

Reference List

Björk, J, Malmqvist, E, Rylander, L & Rignell-Hydbom, A 2017, ‘An efficient sampling strategy for selection of biobank samples using risk scores’, Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, vol. 45, no. 17, pp. 41-44.

Chankseliani, M 2018, ‘Four rationales of HE internationalization: perspectives of U.K. universities on attracting students from former soviet countries’, Journal of Studies in International Education, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 53-70.

China Higher Education 2019, Working with student recruitment agencies. Web.

Clark-Gordon, CV, Workman, KE & Linvill, DL 2017, ‘College students and Yik Yak: an exploratory mixed-methods study’, Social Media and Society, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 1-10.

Dalessandro, C 2018, ‘Recruitment tools for reaching millennials: the digital difference’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 1-10.

Dewasiri, NJ, Weerakoon, YK & Azeez, AA 2018, ‘Mixed methods in finance research: the rationale and research designs’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 1-10.

Ellard-Gray, A, Jeffrey, NK, Choubak, M & Crann, SE 2015, ‘Finding the hidden participant: solutions for recruiting hidden, hard-to-reach, and vulnerable populations’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, vol. 14, no. 15, pp. 1-18.

Farrell, G, Tseloni, A & Tilley, N 2016, ‘Signature dish: triangulation from data signatures to examine the role of security in falling crime’, Methodological Innovations, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1-11.

Fetters, MD & Molina-Azorin, JF 2019, ‘Rebuttal – conceptualizing integration during both the data collection and data interpretation phases: a response to David Morgan’, Journal of Mixed Methods Research, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 12-14.

Gale, T & Parker, S 2017, ‘Retaining students in Australian higher education: cultural capital, field distinction’, European Educational Research Journal, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 80-96.

Garner, M, Wagner, C & Kawulich, B (eds) 2016, Teaching research methods in the social sciences, Routledge, London.

Green, W 2019, ‘Engaging students in international education: rethinking student engagement in a globalized world’, Journal of Studies in International Education, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 3-9.

Hodge, EM, Salloum, SJ & Benko, SL 2016, ‘(Un)commonly connected: a social network analysis of state standards resources for English/language arts’, AERA Open, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 1-13.

Huang, Z, Wang, T & Li, X 2015, ‘The political dynamics of educational changes in China’, Policy Futures in Education, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 24-41.

Hyams-Ssekasi, D, Mushibwe, CP & Caldwell, EF 2014, ‘International education in the United Kingdom: the challenges of the golden opportunity for black-African students’, SAGE Open, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 1-10.

Kuckartz, U 2014, Qualitative text analysis: a guide to methods, practice and using software, SAGE, London.

Morgan, DL 2019, ‘Commentary – after triangulation, what next?’, Journal of Mixed Methods Research, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 6-11.

Moseholm, E & Fetters, MD 2017, ‘Conceptual models to guide integration during analysis in convergent mixed methods studies’, Methodological Innovations, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 1-10.

Özoğlu, M, Gür, BS & Coşkun, İ 2015, ‘Factors influencing international students’ choice to study in Turkey and challenges they experience in Turkey’, Research in Comparative and International Education, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 223-237.

Perez-Encinas, A & Rodriguez-Pomeda, J 2018, ‘International students’ perceptions of their needs when going abroad: services on demand’, Journal of Studies in International Education, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 20-36.

Popkewitz, TS, Feng, J & Zheng, L 2018, ‘Calculating the future: the historical assemblage of empirical evidence, benchmarks & PISA’, ECNU Review of Education, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 107-118.

Rasmussen, P, Larson, A, Rönnberg, L & Tsatsaroni, A 2015, ‘Policies of ‘modernisation’ in European education: enactments and consequences’, European Educational Research Journal, vol. 14, no. 6, pp. 479-486.

Research Rundown 2016, Mixed methods research designs. Web.

Schatz, M 2016, ‘Engines without fuel? – empirical findings on Finnish higher education institutions as education exporters’, Policy Futures in Education, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 392-408.

Shaheen, N 2016, ‘International students’ critical thinking-related problem areas: UK university teachers’ perspectives’, Journal of Research in International Education, vol. 15, no.1, pp. 18-31.

Smith, B & Sparkes, AC (eds) 2016, Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise, Taylor & Francis, London.

SML 2019, How to find suitable agencies in China. Web.

Uprichard, E & Dawney, L 2019, ‘Data diffraction: challenging data integration in mixed methods research’, Journal of Mixed Methods Research, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 19-32.

Willig, C & Rogers, WS (eds) 2017, The SAGE handbook of qualitative research in psychology, SAGE, London.

Zhang, C & Fagan, C 2016, ‘Examining the role of ideological and political education on university students’ civic perceptions and civic participation in mainland China: some hints from contemporary citizenship theory’, Citizenship, Social and Economics Education, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 117-142.