West and East Aesthetic Interaction: Van Gogh’s Bridge in the Rain (after Hiroshige) vs. Bichitr’s Jahangir Seated on an Allegorical Throne

The Age of Discovery led to intense cultural interaction between West and East allowing European and Asian artists to mutually affect each other’s aesthetic traditions.

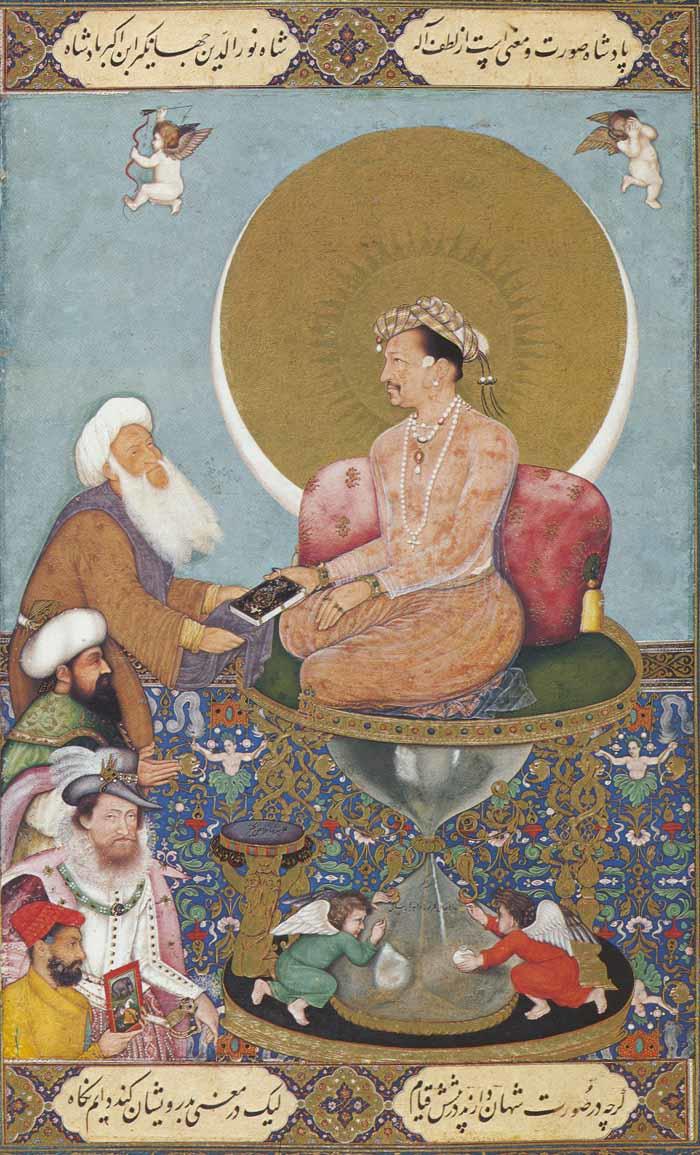

Bichtir’s Jahangir Seated on an Allegorical Throne (see figure 2) is dated the as early 1620s. Jahangir depicted in the painting was on of Mughals who ruled in India from 1526 till 1857. Interestingly, Mughals “descended from two great ruling lineages, the Timurids and the Mongols,” and their empire “extended across India and Persia” (Ferguson 38). As curators of Smithsonian’s Sackler Gallery stated, “The Mughals affirmed their legitimacy as heirs of the Timurids through artistic, literary, and architectural patronage,” (qtd. in Ferguson 38).

Thus, three Mughal rulers known for encouraging and supporting Indian artists were Akbar, Jahangir, and Shah Jahan. According to Diamond, “the Mughals were the apogees of sophistication in the Islamic world, and they created an art that was utterly revolutionary and totally Indian and deeply connected to the broader world, including Europe,” (qtd. in Ferguson 38). Hence, Bichitr was one of Mughals’ court painters supposed “to create distinctive and intricate paintings rich with color from the Mughal Empire” (Ferguson 38). Furthermore, during his rule (1605-1627) Jahangir granted Great Britain (under the rule of King James I) official permission to come and trade in India. As a result of intense trading, India and Great Britain exchanged not only goods but also art pieces and cultural traditions.

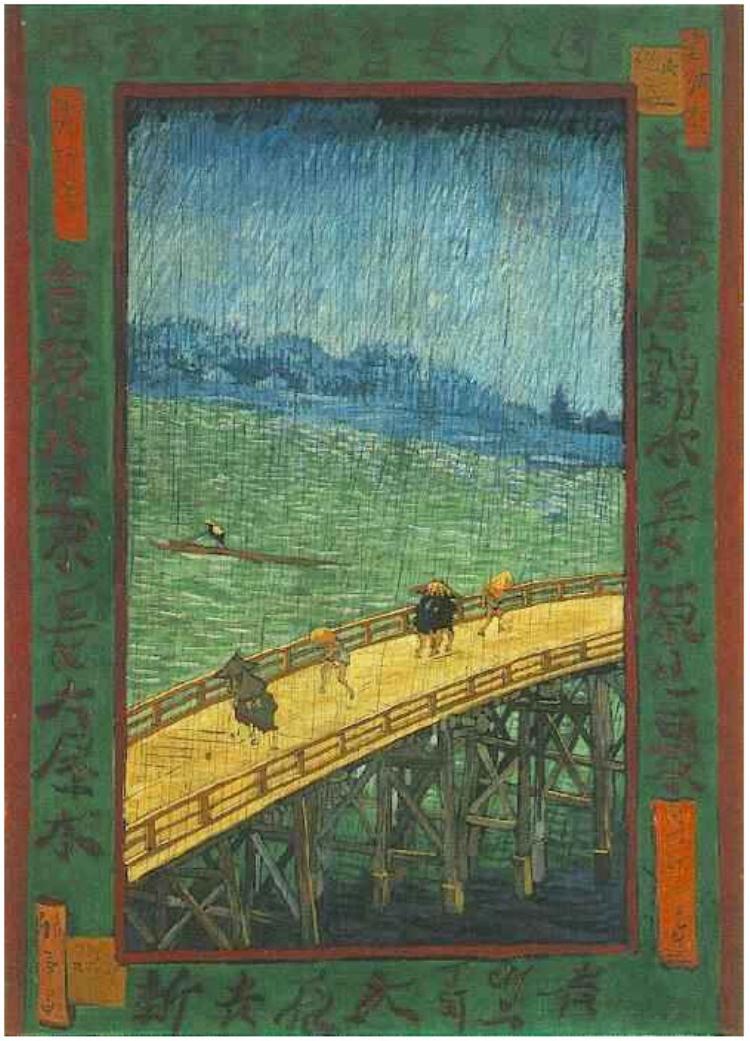

Van Gogh’s Bridge in the Rain (after Hiroshige) (see figure 1) dates back to 1887, the period Van Gogh spent in Paris. After meeting “modern artists like Claude Monet,” “a new generation of artists at Fernand Cormon’s studio, including Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Emile Bernard,” Van Gogh started experimenting with his style (“From Dark to Light” par. 1).

Historically, the end of the eighteenth century involved crucial changes in politics in France: defeat in Franco-Prussian, the fall of Napoleon III, the foundation of the French Third Republic. Following the bourgeois women also took an active part in their social life. Moreover, numerous scientific discoveries in physics, chemistry, psychology, biology, and other subjects gave a boost of energy to French society.

Hence, the end of the nineteenth century in France can be characterized by abrupt changes in political and social life, the tempestuous development of science, technology, and likewise art. During this short period of time, France, in particular, demonstrated a vast range of Modernism art styles, namely, naturalism, romanticism, impressionism; prominent artists displayed their masterpieces for the audience in numerous exhibitions. Therefore, goods and cultural pieces from all over the world came to Europe and France, in particular, adding new perspectives to its active development.

Hence, Van Gogh was thrilled by the new environment. He started using brighter colors and developed “his own style of painting, with short brush strokes” (“From Dark to Light” par. 2). Furthermore, Van Gogh found a new form of inspiration in “Japanese woodcuts, which sold in large quantities in Paris” (“From Dark to Light” par. 2). However, he was not the only one interested in japonisme as Degas, Gaugin, Toulouse-Lautrec also “studied Japanese prints and were influenced by their colors, composition, and subject matter” (Leuthold 180).

Japanese artists Hokusai and Hiroshige made “ukiyo-e prints – picture of the Floating World” that “portrayed actors, geishas, landscapes, stories, and everyday life in Japan from the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries” for distribution around the world (Leuthold 180). Hence, Van Gogh presented his own interpretation of one of Hiroshige’s works and painted Bridge in the Rain (see figure 1). The painting shows that Van Gogh was taken by “bold outlines, cropping and color contrasts” in Japanese prints (“From Dark to Light” par. 2). However, short brush strokes and bright colors characterize Van Gogh’s painting style in contrast with Hiroshige’s one (see figure 1).

Furthermore, comparisons of Van Gogh’s (see figure 1) and Bichitr’s (see figure2) works in terms of colors reveal the coloristic difference between the two paintings and two aesthetic traditions: western and eastern ones. Namely, Van Gogh uses bright primary yellow and blue colors and also bright secondary green and orange colors (see figure 1). In contrast, Bichitr prefers tertiary, quaternary, and even quinary colors (russet, plum, sage, citron, orange, buff, khaki) (see figure 2).

In terms of subject matter, Van Gogh depicts the Japanese landscape with ordinary people crossing the bridge or floating along the river (see figure 1). According to Leuthold, Van Gogh tried to “capture the mood of the spirit of a landscape” and express “the vitality of place” (180). European impressionist and modernist traditions of portraying small figures of people on boulevards and in cafes are also reflected in the choice of this subject matter. In contrast, Bichitr’s subject of matter is an allegorical depiction of Mughal ruler Jahangir (see figure 2). This painting contains a “world within a world” and has “symbolism and allegory” around the central figure of the emperor (Ferguson 39).

According to Welch’s commentary, although putti “have inscribed it with the wish that he [Jahangir] might live a thousand years”, hourglass symbolizing Jahangir’s throne shows that his time has almost run out, meaning that “the Emperor is turning from this world to the next” (qtd. in “Jahangir (d.1627) preferring Sufi shaikhs over King James I of England; by Bichitr, earlier 1620’s” par. 2). By Welch, the emperor handles a book “to the saint… not to the Ottoman sultan… nor to King James I of England… and not even to Bichitr, a symbolic ruler of art” (qtd. in “Jahangir (d.1627) preferring Sufi shaikhs over King James I of England; by Bichitr, earlier 1620’s” par. 2).

The meaning of this gesture is inscribed on the painting, “Though outwardly shahs stand before him, he fixes his gazes on dervishes”. Moreover, as noted by Malecka, “the decoration of the Mughal thrones with solar motives… created the celestial space for the Emperor – “The Sun” (24). Hence, Jahangir welcomes foreigners to come but shows his ultimate might as the sun and asks his descendants to value indigenous cultural and religious traditions.

Although both works represent the characteristic style of their authors, the influence of foreign aesthetic tradition is evident in Van Gogh’s and Bichitr’s paintings. Regarding composition and subject matter, Van Gogh uses perspective and proportions of Japanese art, namely coping Hiroshige’s angled horizon, his linear perspective, simple and direct composition (see figure 1). According to Beach, Bichitr’s “interest in portraiture and the identifiable European sources makes this the most “European” of all Jahangir’s portraits” (104). Namely, Bichitr copies the Western portrait of King James I and incorporates putti in his artwork (see figure 2).

Therefore, despite differences in colors, motifs, subject matters, and styles Van Gogh’s Bridge in the Rain (after Hiroshige) and Bichitr’s Jahangir Seated on an Allegorical Throne make a good comparison because they both testify of mutual influence of West and East aesthetic traditions in terms of cultural and visual perception of the world.

Art Works References

Works Cited

Beach, Milo Cleveland. The New Cambridge History of India: Mughal and Rajput Painting, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992. Print.

Ferguson, Barbara. “Worlds within Worlds: Imperial Paintings from India and Iran.” The Washington Report on Middle East Affairs 31.7 (2012): 38-39.

From Dark to Light. n.d. Web.

Jahangir (d.1627) preferring Sufi shaikhs over King James I of England; by Bichitr, earlier 1620’s. n.d. Web.

Leuthold, Steven. Cross-Cultural Issues in Art: Frames for Understanding, New York: Routledge, 2010. Print.

Malecka, Anna. “Solar Symbolism of the Mughal Thrones. A Preliminary Note.” Arts Asiatiques 54.1 (1999): 24-32.