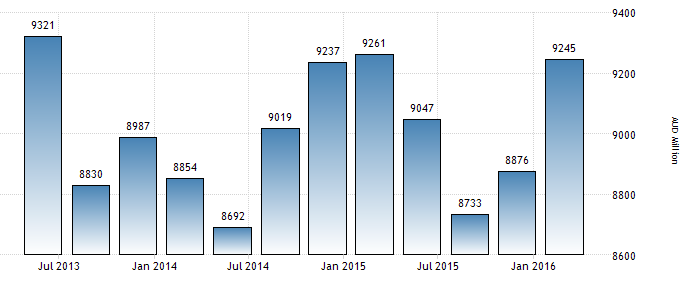

The agricultural sector is one of the definers of the Australian GDP. Thus, it continues to grow in its value, but it accounts only for the fifth position (9,245 million AUD) after construction (32,094 million), manufacturing (24,366 million), mining (38,935 million), and public administration (23,179 million) (“Australia GDP from Agriculture,” 2016). The current situation in the agricultural sphere is one of the critical drivers for the need for government intervention and the development of new reforms. Consequently, the primary goal of this paper is to analyze the current condition of Australian agriculture and its import and export opportunities.

Thus, the current export and import image of the Australian agricultural sector is rather predictable. For instance, Australia starts to be less dependent on the imports due to the interest of the governmental authorities in the prosperity of the local farmers (“Australian Government: Agriculture” par. 5). Nonetheless, the import is $2,969,524 thousand (“World Integrated Trade Solution: Import” par. 1).

Thus, the major importers are the United States of America, China, and Pacific countries (“World Integrated Trade Solution: Import” par. 1). As for the exports concerning vegetables, it remains evident that Australia tries to enhance its external trade by taking advantage of new opportunities. Nowadays, the export accounts for $12,226,517 thousand, and the primary partners are China, Japan, and East Asia & Pacific (“World Integrated Trade Solution: Export” par. 1). It could be said that this analysis reveals the exporting nature of the Australian vegetable market and the prioritization of Asia & Pacific regions.

Despite the prosperity of the agricultural sphere in Australia, the business can consider international expansion. Currently, these economic sectors experience fluctuations, but, overall, the growth in a positive direction cannot be disregarded (see Figure 1). Thus, based on the analysis conducted above, Australian producers of vegetables such as tomatoes should continue their pursuit of growth in Asian countries such as the South of China. The selection of this region is defined by a well-defined logistic path and low transportation costs.

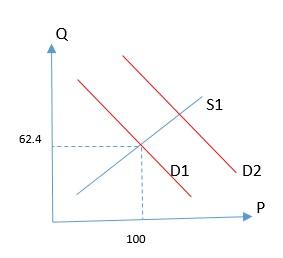

Nonetheless, it is critical to define the overall supply and demand conditions of vegetables in Asian countries since they are the major partners of Australia. This market is prosperous, as the demand for fresh vegetables tends to increase by up to 90% (Holmer et al. 27). Thus, South-Eastern Asia has the lowest supply of vegetables by having 62.4 kg per capita (Holmer et al. 27). It could be assumed that the demand exceeds the supply, and there is a possibility for expansion (see Figure 2).

The development of world trade policies has a beneficial impact on Australian farmers’ growth. In this case, the new policy events, such as the global financial crisis, had a beneficial impact on businesses and helped them restore their image and enhance financial performance. Consequently, using this opportunity indicates the potential growth of this business sector and international recognition.

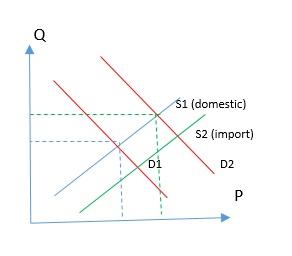

Simultaneously, there are several aspects, which will define the establishment of the businesses in the agricultural sphere. In this case, the product could be one of the vegetables, such as tomatoes. The potential customers of the product are the retailers and processing plants. Nonetheless, the product will be delivered to the final consumer such as the average household with medium to low income in the South of China. In this case, it is critical to analyze supply and demand in the region. Due to the development of the processing industry, the demand for tomatoes will continue to rise (Holmer et al. 27).

Thus, the suppliers tend to respond to the changes rapidly, but the quality of the produce of local firms is not able to satisfy the demands of the national population (Gale, Hansen, and Jewison 15) (see Figure 3). This factor underlines the need for the agricultural imports and provides a distinct opportunity to the Australian producers of tomatoes in the Chinese market (Gale, Hansen, and Jewison 15). Nonetheless, the newcomers have to be able to understand the threat of the international competitors, as the Chinese marketplace is highly attractive.

Thus, the rising concerns about the food security are the drivers for the development of the reforms in the sphere. One of the potential trade barriers is the price volatility and intensified competition at the global arena (“Australian Government: Agriculture” par. 5). It creates difficulties for the local producers and does not allow the sufficient growth of GDP. Australian government actively contributes to offering the favorable export environment to the agricultural farmers in Australia (“Australian Government: Agriculture” par. 5).

It decreases the demand and price fluctuations but causes the shift in competition concurrently. In spite of positive intentions of free trade, this economic phenomenon will not be able to affect the local manufacturers beneficially. The majority of the local producers require protection, especially, in the agricultural sector. The concept of free trade implies introducing no restrictions or quotas on exports or imports and providing a free environment for any trade activities (Cohn 206). Nonetheless, pursuing this scheme might lead to the loss of the market share and price volatility of the domestic farmers. However, it will have a positive impact on the introduced tomato producer.

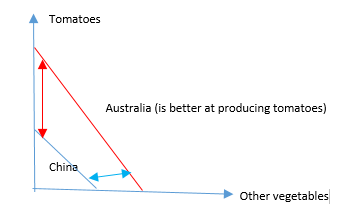

Notwithstanding the role of practical nature of the business environment, the theoretical concepts such as comparative advantage theory have a critical reflection on agricultural producers. The advancement of technology in Australia assists the country in selling products for the lower prices than the farmers in China. In this case, Australian farmers of tomatoes will be able to provide a more suitable price-to-quality ratio than its Chinese domestic competitors while exploiting the principle of comparative advantage. Figure 4 reflects that China should buy tomatoes from Australia, and Australia should focus on exporting other vegetables from China.

In the end, the trade flow data helps identify current supply and demand in the agricultural sector in Australia. It was revealed that it is reasonable for the Australian farmers to expand to the Chinese market due to the well-established partnership and the lack of domestic supply in China. Thus, recent governmental interventions support the export initiatives and make expansion of tomato farm a possibility.

It remains evident that the productivity of the tomato farm in the international market is dependent on the actions of the competitors and their value proposal. Therefore, taking advantage of technology will help Australian producer gain comparative competitive advantage and occupy Chinese vegetable market.

Works Cited

Australia GDP from Agriculture. 2016. Web.

Australian Government: Agriculture. 2016. Web.

Cohn, Steven. Reintroducing Macroeconomics: A Critical Approach. London: Routledge, 2015. Print.

Gale, Fred, James Hansen, and Michael Jewison. China’s Growing Demand for Agricultural Imports. 2015. Web.

Holmer, Robert, Grisana Linwattana, Prem Nath, and Suwit Chaikiattiyos. High Values Vegetables in Southeast Asia: Production, Supply, and Demand. Tainan: AVRDC The World Vegetable Center, 2013. Print.

World Integrated Trade Solution: Export. 2015. Web.

World Integrated Trade Solution: Import. 2015. Web.